New reparations model makes Kremlin kleptocracy pay for Ukraine’s reconstruction

Democracy Digest

October 31, 2022

Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction should be financed by funds sanctioned from the Kremlin’s kleptocrats, argues Azeem Ibrahim, Director of Special Initiatives at the New Lines Institute of Strategy and Policy.

In thirteen legal conclusions, new Multilateral Action Plan on Reparations spells out an international legal process to identify, collect, and distribute sanctioned Russian money, for the benefit of Ukraine, he writes for New Europe:

- Our legal analysis envisages the creation of a new fund and compensation commission, drawing on the precedent of the United Nations Compensation Commission (UNCC) established to compensate Kuwait in the face of Iraq’s invasion in 1990.

- Signatories of this agreement would commit to seize Russian assets within their jurisdiction, in accordance with their national and constitutional requirements, and place them into the fund, for subsequent distribution by the new compensation commission.

- Ukrainians and the Ukrainian state could petition a commission for reconstruction and reparation funds. Once evidence of necessity was produced, the commission could draw on funds gathered by these methods and disburse the money.

Karen Dawisha’s book Putin’s Kleptocracy noted that hundreds of billions of dollars are paid to regime affiliates in bribery money alone, Ibrahim adds. A creative treaty regime could render those assets available for the fund.

Karen Dawisha’s book Putin’s Kleptocracy noted that hundreds of billions of dollars are paid to regime affiliates in bribery money alone, Ibrahim adds. A creative treaty regime could render those assets available for the fund.

In combination with several U.N. resolutions and a ruling from the International Court of Justice that have found that Russia has waged a war of aggression, the International Law Commission’s Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts establish the international legal basis for transferring Russia’s reserves to Ukraine, adds Robert Zoellick, a former U.S. trade representative, deputy U.S. secretary of state and World Bank president.

In doing so, the U.S. and allied countries wouldn’t be taking Russian reserves for themselves; they would transfer them to an international fund for compensation. The U.S. should also propose to the U.N. that frozen Russian reserves could finance a U.N. claims commission to compensate low-income countries victimized by Russia’s shock to food supplies, he writes for the Wall Street Journal.

How do we build a truly comprehensive international response to stymie kleptocratic regimes like Russia? asks Ryan Arick, Assistant Program Officer at the International Forum for Democratic Studies.

“Sustaining the Momentum: Countering Kleptocracy in Russia and Beyond” was the focus of a recent event at which experts and practitioners discussed democracies’ collaborative efforts to increase transparency in the financial sector, leverage sanctions against malign actors, and connect anti-kleptocracy actors across sectors. But more needs to be done, not just related to the war in Ukraine, but also in the broader global context where kleptocratic networks can thrive, he writes:

USAID Executive Director of the Anti-Corruption Task Force Shannon N. Green (@ShannonNGreen1) outlined USAID’s current efforts to meet this challenge, which include the launch of a “de-kleptification guide” and a global support fund for independent journalists.

USAID Executive Director of the Anti-Corruption Task Force Shannon N. Green (@ShannonNGreen1) outlined USAID’s current efforts to meet this challenge, which include the launch of a “de-kleptification guide” and a global support fund for independent journalists.- Nate Sibley (@NateSibley) advocated for a democratic, global economy founded on “friend-shoring,” or increasing coalitions among like-minded countries, to protect vital institutions and reduce vulnerabilities to malign influence.

- As for the professional enabling industries, the U.S. Helsinki Commission’s Paul Massaro (@apmassaro3) urged, if we “can clean those sectors up, we can effectively defang our adversaries.”

- Publish lists of targeted assets, or appoint commissioners to oversee anti-corruption work and serve as points of contact for civil society and others focused on the fight against kleptocracy, said Nikita Kulachenkov (@nekulachenkov).

Last year, the Biden Administration released a presidential memorandum identifying corruption as a core national security threat; the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) launched the Anti-Corruption Task Force; and several pieces of legislation have been introduced to target professions in open societies that enable kleptocrats to hide their illicit funds, Arick adds. RTWT

Last year, the Biden Administration released a presidential memorandum identifying corruption as a core national security threat; the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) launched the Anti-Corruption Task Force; and several pieces of legislation have been introduced to target professions in open societies that enable kleptocrats to hide their illicit funds, Arick adds. RTWT

For the past several years, Oliver Bullough, a former Russia correspondent, has guided “kleptocracy tours” around London, explaining how dirty money from abroad has transformed the city, the New Yorker adds. His book, Butler to the World – one of the best of 2022 – argues that the UK actively solicited such corrupting influences, by letting “some of the worst people in existence” know that it was open for business.

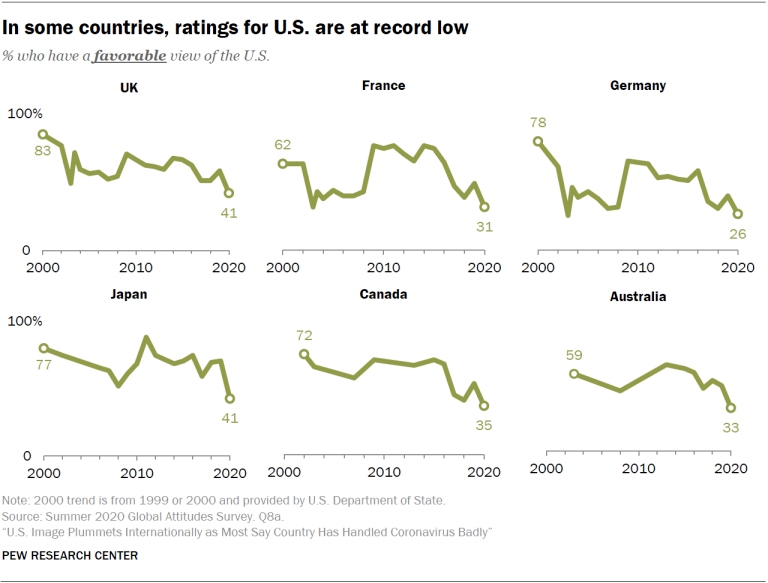

Eighty-five percent of people in other wealthy democracies believe the United States handled the coronavirus pandemic poorly.

Eighty-five percent of people in other wealthy democracies believe the United States handled the coronavirus pandemic poorly. “Despite the trillions of dollars the United States has spent on national security in the past two decades, it was not prepared to combat this wholly predictable threat,”

“Despite the trillions of dollars the United States has spent on national security in the past two decades, it was not prepared to combat this wholly predictable threat,”

For China’s one party-state, the West’s promotion of liberal democracy is part of an ideological struggle led by an adversary that is still vastly superior, a situation that Chinese strategists describe as xiqiang woruo (“the West is strong, while China is weak”). The hostile forces are liberal democratic ideals and their corollaries – constitutional democracy, universal values, individual rights, economic liberalism, free media – which have been identified by the CCP as deadly “

For China’s one party-state, the West’s promotion of liberal democracy is part of an ideological struggle led by an adversary that is still vastly superior, a situation that Chinese strategists describe as xiqiang woruo (“the West is strong, while China is weak”). The hostile forces are liberal democratic ideals and their corollaries – constitutional democracy, universal values, individual rights, economic liberalism, free media – which have been identified by the CCP as deadly “ Beijing believes the West has used its power in this domain to dominate the international system and the world order. Words are not merely instruments of communication used to facilitate exchanges and discussions; they convey concepts, ideals, and values that are the foundation for the norms on which the international architecture is constructed and thus determine how the world order is run. In sum:

Beijing believes the West has used its power in this domain to dominate the international system and the world order. Words are not merely instruments of communication used to facilitate exchanges and discussions; they convey concepts, ideals, and values that are the foundation for the norms on which the international architecture is constructed and thus determine how the world order is run. In sum:  “I had some specific practical ideas about how to protect our information system. But many people in the audience thought I was aiming too low. The real, essential issue was surely regulating Facebook? My response is that we need to do both,” he writes:

“I had some specific practical ideas about how to protect our information system. But many people in the audience thought I was aiming too low. The real, essential issue was surely regulating Facebook? My response is that we need to do both,” he writes: Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, China has behaved in increasingly nefarious ways. Domestically, it has shifted from one-party to one-man rule and become a surveillance state that locks up innocent people by the hundreds of thousands in concentration camps. Abroad,

Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, China has behaved in increasingly nefarious ways. Domestically, it has shifted from one-party to one-man rule and become a surveillance state that locks up innocent people by the hundreds of thousands in concentration camps. Abroad,  Among other issues, the Committee will seek testimony about:

Among other issues, the Committee will seek testimony about: Viktor Orbán is

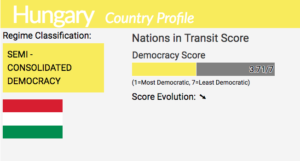

Viktor Orbán is This year Freedom House deemed Hungary only “partly free,” the first time in its history an EU member state has been denied the designation “free.”

This year Freedom House deemed Hungary only “partly free,” the first time in its history an EU member state has been denied the designation “free.” “You know the growth rates of Italy and some other European countries are much lower than Hungary’s. The Hungarian government is in a certain way very pro-business and is happy to attract business wherever it comes from with low taxes or longer working hours,” he adds.

“You know the growth rates of Italy and some other European countries are much lower than Hungary’s. The Hungarian government is in a certain way very pro-business and is happy to attract business wherever it comes from with low taxes or longer working hours,” he adds. “The most important cause of their pessimism is bad policy and bad leadership,” said Minxin Pei, a professor at Claremont McKenna College [and contributor to the NED’s

“The most important cause of their pessimism is bad policy and bad leadership,” said Minxin Pei, a professor at Claremont McKenna College [and contributor to the NED’s There is

There is  The group seems to have “all the hallmarks” of a front organization to further Beijing’s interests,

The group seems to have “all the hallmarks” of a front organization to further Beijing’s interests, Increasing Chinese leadership in the Middle East is served by a

Increasing Chinese leadership in the Middle East is served by a  Opposition demographics are another factor

Opposition demographics are another factor A former intelligence chief in Venezuela who is one of the government’s most prominent figures turned against President Nicolás Maduro on Thursday, calling him a dictator with a corrupt inner circle that has engaged in drug trafficking and courted the militant group Hezbollah,

A former intelligence chief in Venezuela who is one of the government’s most prominent figures turned against President Nicolás Maduro on Thursday, calling him a dictator with a corrupt inner circle that has engaged in drug trafficking and courted the militant group Hezbollah, There have been

There have been  “The opposition is more united than ever, the pressure is very intense, both within this hemisphere and the major European countries, and so there needs to be a negotiation of some sort to give some protections or some guarantees to the armed forces who are guilty of human rights violations and other criminal activities,”

“The opposition is more united than ever, the pressure is very intense, both within this hemisphere and the major European countries, and so there needs to be a negotiation of some sort to give some protections or some guarantees to the armed forces who are guilty of human rights violations and other criminal activities,” Our research, reflected in two recently published Wilson Center reports, examines differences in

Our research, reflected in two recently published Wilson Center reports, examines differences in