Temas de relações internacionais, de política externa e de diplomacia brasileira, com ênfase em políticas econômicas, em viagens, livros e cultura em geral. Um quilombo de resistência intelectual em defesa da racionalidade, da inteligência e das liberdades democráticas.

O que é este blog?

Este blog trata basicamente de ideias, se possível inteligentes, para pessoas inteligentes. Ele também se ocupa de ideias aplicadas à política, em especial à política econômica. Ele constitui uma tentativa de manter um pensamento crítico e independente sobre livros, sobre questões culturais em geral, focando numa discussão bem informada sobre temas de relações internacionais e de política externa do Brasil. Para meus livros e ensaios ver o website: www.pralmeida.org. Para a maior parte de meus textos, ver minha página na plataforma Academia.edu, link: https://itamaraty.academia.edu/PauloRobertodeAlmeida;

Meu Twitter: https://twitter.com/PauloAlmeida53

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/paulobooks

quinta-feira, 4 de junho de 2020

John Maynard Keynes, by M. G. Hayes - Book Review by A. Reeves Johnson

terça-feira, 17 de dezembro de 2019

Consequências econômicas de Mister Keynes: a ascensão de Hitler - Edward W. Fuller (Mises Wire)

The Economic Consequences of the Peace: 100 Years Later

Mises Wire, December 16, 2019

Introduction

Britain’s War-Debt Problem

At the opening of the Peace Conference, this country should propose to the United States that all debts incurred between the Governments of the Associated countries prior to January 1st, 1919, should be cancelled. … Failing such a settlement the war will end with a net-work of heavy tributes payable from one Ally to another. A certain amount of indemnity will be recoverable from the enemy, but this is likely to be of a less amount than the indemnities which the Allies will be paying to one another. This is an improper conclusion to such a war as the present one. … Indeed, failing a readjustment, the financial sacrifice of the United States will have been disproportionately small, and Germany will be the only Power free from the financial grip of the U.S.8

No doubt it would be a very good thing if the United States would propose or support a universal cancellation of debt, but my information from Paris is that they show no inclination to do anything of the kind. … To propose the mere cancellation of debt looks as if we were trying to shift the whole burden on to America.10

If all the above Inter-Ally indebtedness were mutually forgiven, the net result on paper (i.e. assuming all the loans to be good) would be a surrender by the United States of about $10,000,000,000 and by the United Kingdom of about $4,500,000,000. France would gain about $3,500,000,000 and Italy about $4,000,000,000. But these figures overstate the loss of the United Kingdom and understate the gain to France. … [T]he relief in anxiety which such a liquidation of the position would carry with it would be very great. It is from the United States, therefore, that the proposal asks generosity.12

German Reparations

Germany is liable up to the full extent of the injury she has caused to the Allied and Associated Nations. … The Allied and Associated Governments demand accordingly that Germany render payment for the injury which she has caused up to the full limit of her capacity. … Germany shall hand over immediately (a) the whole of her mercantile marine, (b) the whole of her gold and silver coin and bullion in the Reichsbank and all other banks; (c) the whole of the foreign property of her nationals situated outside Germany, including all foreign securities, foreign properties and business and concessions.14

(1) The amount of payment to be made by Germany in respect of Reparation and the costs of the Armies of Occupation might be fixed at $10,000,000,000(2) The surrender of merchant ships … war material … State property … public debt, and Germany’s claims against her former Allies, should be reckoned as worth the lump sum of $2,500,000,000(3) The balance of $7,500,000,000 should not carry interest pending its repayment, and should be paid by Germany in thirty annual installments of $250,000,000, beginning in 1923.20

The Transfer Problem

Two eventualities have to be sharply distinguished; the first, in which the usual course of trade is not gravely disturbed by the payment. … The second, in which the amount involved is so large that it cannot be paid without a drastic disturbance of the course of trade and a far-reaching stimulation of the exports of the paying country. … An indemnity high enough to absorb the whole of Germany’s normal surplus, for investment abroad and for building up foreign business and connections must certainly be advantageous to this country and correspondingly injurious to the enemy.21

to obtain all the property which can be transferred immediately or over a period of three years, levying this contribution as ruthlessly and completely, so as to ruin entirely for many years to come Germany’s overseas development and her international credit; but having done this … to ask only a small tribute over a term of years.22

We can secure from her moderate [annual] payments, on the sort of scale, for example, on which she might have been building up new foreign investments, without stimulating her exports as a whole to a greater activity than they would enjoy otherwise. This is the correct course for Great Britain from the standpoint of her own self-interest only.23

We, who are imperialists … think that British rule brings with it an increase of justice, liberty, and prosperity; and we administer our Empire not with a view to our pecuniary aggrandizement. … Germany’s aims are not such. … [S]he looks rather to definite material gains. … [W]e distrust her diplomacy, we distrust her international honesty, we resent her calumnious attitude towards us. She envies our possessions; she would observe no scruple if there was any prospect of depriving us of them. She considers us her natural antagonist. She fears the preponderance of the Anglo Saxon race.24

An excess of exports is not a prerequisite for the payment of reparations. The causation, rather, is the other way round. The fact that a nation makes such payments has the tendency to create such an excess of exports. There is no such thing as a “transfer” problem. If the German Government collects the amount needed for the payments (in Reichsmarks) by taxing its citizens, every German taxpayer must correspondingly reduce his consumption either of German or of imported products. In the second case the amount of foreign exchange which otherwise would have been used for the purchase of these imported goods becomes available. In the first case the prices of domestic products drop, and this tends to increase exports and thereby the amount of foreign exchange available. Thus collecting at home the amount of Reichsmarks required for the payment automatically provides the quantity of foreign exchange needed for the transfer. … The inflow of Germany’s payments necessarily rendered the receiving countries’ balance of trade “unfavorable.” Their imports exceeded their exports because they collected the reparations. From the viewpoint of mercantilist fallacies this effect seemed alarming.26

Reassessing the Mythology

The sum we ourselves owe to the United States must undoubtedly be regarded as very real debts. … Such a burden will cripple our foreign development in other parts of the world, and will lay us open to future pressure by the United States of a most objectionable description.31

The Consequences of Keynes

Notes

1. Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes: Hopes Betrayed (New York: Viking, 1983), p. 384.

- 2. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 2, p. 175.

- 3. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 2, pp. 177–78.

- 4. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 2, p. 172.

- 5. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 16, p. 3.

- 6. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 18, pp. 383–84.

- 7. Roy Harrod, The Life of John Maynard Keynes (London: Macmillan, 1951), p. 206.

- 8. “Memorandum on the Treatment of Inter-Allied Debt Arising Out of the War,” The John Maynard Keynes Papers (Cambridge, UK: King’s College, PT/7/11–21), p. 16.

- 9. In Edward M. House and Charles Seymour, What Really Happened at Paris: The Story of the Peace Conference, 1918–1919 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921), p. 289.

- 10. In The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 16, p. 437.

- 11. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 2, pp. 176–77.

- 12. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 2, pp. 172–73.

- 13. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 3, p. 113, vol. 18, pp. 377, 381–82.

- 14. “Reparation and Indemnity,” The John Maynard Keynes Papers (Cambridge, UK: King’s College, RT/14/31–34). Available at https://mises.org/wire/keynes-and-versailles-treatys-infamous-article-231.

- 15. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 16, pp. 314–34.

- 16. David Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties (London: Victor Gollancz, 1938), p. 446.

- 17. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 16, pp. 344–83.

- 18. Charles Hession writes, “when the conference became bogged down on the amount of reparations to be demanded of the defeated nation, it was his suggestion that the exact sum be left undetermined.” John Maynard Keynes (New York: Macmillan, 1984), p. 147. For documentation, see https://mises.org/wire/keynes-and-versailles-treatys-infamous-article-231.

- 19. Donald Moggridge writes, “The significant draftsman of the clause were Keynes and John Foster Dulles.” Maynard Keynes: An Economist’s Biography (New York: Routledge, 1992), pp. 308, 331, 346. For documentation, see https://mises.org/wire/keynes-and-versailles-treatys-infamous-article-231.

- 20. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 2, p. 166.

- 21. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 16, pp. 379–81.

- 22. Ibid., p. 382.

- 23. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 3, p. 109.

- 24. “Speech to the Cambridge Union, 20 January 1903,” The John Maynard Keynes Papers (Cambridge, UK: King’s College, OC/5/4–26), p. 24.

- 25. Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes: Economist as Savior (New York: Viking, 1992), p. 311.

- 26. Ludwig von Mises, Omnipotent Government (1944; repr. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011), p. 241.

- 27. Robert Skidelsky, "Commanding Heights," p. 6. Available at https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/pdf/int_robertskidelsky.pdf.

- 28. Robert A. Mundell, in Bertil Ohlin: A Centennial Celebration (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2002), p. 259n17; Benjamin Steil, The Battle of Bretton Woods (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), p. 149.

- 29. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 16, 198.

- 30. Keynes, quoted in Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War (New York: Basic Books, 1999), pp. 327, 329.

- 31. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 16, p. 418.

- 32. Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes, p. 20.

- 33. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 16, p. 419.

- 34. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 18, pp. 373–76, 382–86, 387–90.

- 35. In Harold L. Wattel, The Policy Consequences of John Maynard Keynes (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1986), p. 117.

- 36. Benjamin Steil writes, “[the US] would for years use Lend-Lease to press the British relentlessly for financial and trade concessions that would eliminate Britain as an economic and political rival in the postwar landscape.” He continues, “This would necessarily involve dismantling the structural supports of the empire. No Briton read the U.S. Treasury’s intentions better, and resented them more bitterly, than Maynard Keynes.” See Battle of Bretton Woods (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 108, 110.

- 37. Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan (New York: Grove Press, 2010), p. 208.

- 38. Elizabeth Wiskemann, The Europe I Saw (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1968), p. 53.

terça-feira, 11 de junho de 2019

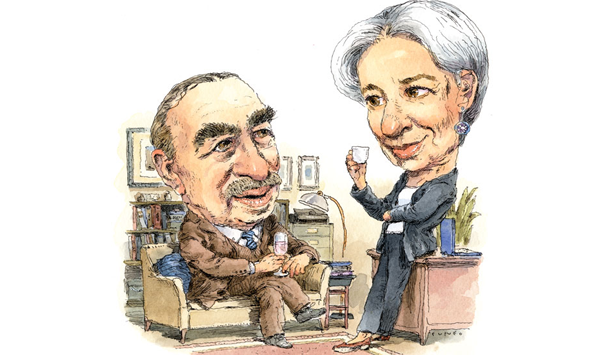

O FMI recebe uma visita de... Lord Keynes - Rahim Kanani, IMF magazine: Finance and Development

“O que Roberto Campos estaria pensando da política econômica?”, Brasília, 30 set. 2004, 4 p. Ensaio colocando RC em conversa com Keynes, Hayek e Marx, no limbo, a propósito do terceiro ano de sua morte. Publicado em formato reduzido no jornal O Estado de São Paulo (sábado, 9/10/2004); divulgado em versão integral no blog Diplomatizzando (6/01/2017; link: http://diplomatizzando.blogspot.com.br/2017/01/ainda-roberto-campos-com-marx-e-hayek.html).

Mas, alguns anos à frente dessa brincadeira, eu também coloquei Tocqueville a serviço do Banco Mundial, primeiro numa visita ao Brasil, depois a vários outros países latino-americanos:

“De la Démocratie au Brésil: Tocqueville de novo em missão”, Brasília, 10 agosto 2009, 10 p. Resumo de relatório da missão ao Brasil empreendida por Alexis de Tocqueville, a pedido do Banco Mundial, para determinar a situação do Brasil em termos de democracia e de economia de mercado. Publicado na Espaço Acadêmico (ano 9, n. 103, dezembro 2009, p. 130-138; ISSN: 1519-6186; link: http://periodicos.uem.br/ojs/index.php/EspacoAcademico/article/view/8822/4947); blog Diplomatizzando (12/07/2011; link: http://diplomatizzando.blogspot.com/2011/07/tocqueville-de-novo-em-missao-o-brasil.html).

“De la (Non) Démocratie en Amérique (Latine): a Tocqueville report on the state of governance in Latin America”, Brasília, 9 junho 2018, 41 p. Paper presented in the Estoril Political Forum; round-table “Brazil and Latin America: the challenges ahead”. Academia.edu (link: https://www.academia.edu/s/a4cbf778cf/de-la-non-democratie-en-amerique-latine-a-tocqueville-report-on-the-state-of-governance-in-latin-america), em Research Gate (link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325809199_De_la_Non_Democratie_en_Amerique_Latine_A_Tocqueville_report_on_the_state_of_governance_in_Latin_America) e divulgado no blog Diplomatizzando (17/06/2018; link: https://diplomatizzando.blogspot.com/2018/06/de-la-non-democratie-en-amerique-latine.html). Publicado na Revista de Estudos e Pesquisas Avançadas do Terceiro Setor, REPATS (vol. 5, n. 1, janeiro-junho 2008, p. 792-842; ISSN: 2359-5299; link: https://portalrevistas.ucb.br/index.php/REPATS/article/view/10020/5909).

Agora leiam esta brincadeira do editorialista da revista do FMI:

Lord Keynes Pays a Visit

Finance & Development, June 2019, Vol. 56, No. 2

Digital Editor, F&D Magazine

International Monetary Fund

References:

(193): 34–51.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.