É sobre esse princípio que foi criada a Google, e antes dela os computadores da Apple.

O artigo abaixo discorre sobre isso.

Ah, sim, e quanto à diplomacia?

Bem, acho que as novas tecnologias aplicados ao trabalho diplomático melhorariam tremendamente sua capacidade de processar informações, embora a capacidade dos homens tomarem decisões sejam muito rudimentar, e prejudicada por todos os preconceitos políticos e as crenças individuais dos decisores.

Acho que a nossa diplomacia está mais para MS--DOS do que para Mac iOS, ou para Google, com perdão da ofensa ao inventor do primeiro sistema operacional dos computadores pessoais.

Enfim, essa é a vida.

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

How Moore’s Law Made Google Possible

Backchannel, February 12, 2015

Gordon

Moore’s famous calculation of the gains in power and economy that would

drive chip production continues to have profound implications for every

enterprise, no matter what the sector. But most of us have difficulty

grasping the full impact of what Moore has laid out. Our handicap is

that we are laboring under the illusion that the impossible is

impossible.

But

those who truly understand Moore’s Law know its corollary: the

impossible is the inevitable. Right after Moore’s prescient

prognostication, anyone with a slide rule — or a Texas Instruments

calculator — could have easily run some numbers and determined that

within a generation there would be computational gains a billionfold or

more. The much more difficult task would be to believe this, let alone

figuring out what it meant for rates of innovation, for businesses, and

even for the human race.

The nonlinear gains that Moore predicted are so mind-bending that it is no wonder that very few were able to bend their minds around it.

But those who did would own the future.

Case

in point is Larry Page. From birth in 1973, Larry Page was incubated in

the growth light of Moore’s Law. His father and mother were computer

scientists. He grew up on Michigan college campuses, never far from a

computer center. He took for granted the dizzying gains in computation

that would come. So he did not think twice about proposing schemes that

exploited the effects of Moore’s Law, especially the big idea he had as a

Stanford graduate student of dramatically improving search by taking

advantage of the links of the World Wide Web.

When

his thesis professor noted that such a task meant capturing the whole

web on Stanford’s local servers, Page was unfazed. With a firm grip of

how much more powerful and cheap tomorrow’s technology would be, he

realized such a feat would eventually be relatively trivial; so would

making the complicated mathematical analysis of those links, which would

have to be done in well under a second. These would be written by

Page’s partner, Sergey Brin, who shared Page’s comfort with the

nonlinear effects of Moore’s Law. Both knew for the first time in

history, the massive computation required to analyze all those links was

within the grasp of grad students. Thus, by recognizing the “new

possible,” Page and Brin were about to do what once was

impossible — instantly combing through all of human knowledge to answer

even the most obscure question.

In interviews, including those I conducted with him while writing In the Plex, my biography of Google, Page has outlined what might be known as his own variation on Moore:

Huge acceleration in computer power and memory

+ rapid drop in cost of same

= no excuse for pursuing wildly ambitious goals

Companies

that develop products for the world in its present state are doomed for

failure, he says. Successful products are created to take advantage of

tools and infrastructure of the future. When Google whiteboards new

products, it assumes they will be powered by technologies that don’t

exist yet, or do currently exist and are prohibitively expensive. It is a

safe bet that in a very short period of time, new technologies will exist

and the cost of memory, computation and transit will fall dramatically.

In fact, Moore’s Law (and similar phenomena in storage and fiber

optics) means that you could bet the house on it. “The easiest thing is

to do some incremental improvements,” says Page. “But that’s guaranteed

to be obsolete over time, especially when it comes to technology.”

A

clear example of this came in 2004 when Google announced Gmail, its

web-based email product. It was not the first entry in the category. But

the competitors offered very limited storage — the most popular product

at the time, Microsoft’s Hotmail, gave users 2 megabytes of free

storage. Users constantly had to pare down their inboxes. Gmail gave

users a gigabyte of

storage — five hundred times the industry standard. (It soon doubled the

amount to 2 gigs.) At the time, it was so unusual that when Gmail was

announced on April 1 of that year, many people regarded it as a prank — how can you give away a gigabyte of data? Indeed,

in 2004, the outlay of such RAM storage to millions of users drained

Google’s resources. Yes, it was costly. But only temporarily. As Page

says, “That’s worked out pretty well for us.”

When Page takes meetings with Google’s employees, he relentlessly badgers them for not proposing more ambitious ideas.

Much worse than failure is failing to think big.

Earlier,

Steve Jobs of Apple had a similar conundrum when releasing the

Macintosh. The problem was that in 1984, technology was not ready for

the computer his team had designed. To provide a satisfactory user

experience, the Macintosh required at least a megabyte of internal

memory, a hard disk drive, and a processor several times speedier than

the Motorola 68000 chip that drove the original. Jobs knew that Moore’s

Law would provide help soon, and wanted to sell the Macintosh initially

priced at a money-losing $2000 to grab market share. But his bosses at

Apple did not understand that setting a low price would only mean losses

temporarily — the company would soon be paying less for much more

powerful chips. Indeed, in a few years the Macintosh had all the power

and storage it needed — but had lost the market momentum to Microsoft.

Ray

Kurzweil, the great inventor and artificial intelligence pioneer now at

Google, has a theory about those who are best suited to create

groundbreaking products.

The common wisdom, he says, is that one cannot predict the future. Kurzweil insists that, because of Moore’s Law and other yardsticks of improvement, you can predict the future.

Maybe

not enough to tell if a specific idea will succeed but certainly well

enough to understand what resources might be available in a few years.

“The world will be a very different place by the time you finish a

project,” he told me in an interview a couple of years back.

The

problem, explains Kurzweil, is that so few people have internalized

that reality. Our brains haven’t yet evolved in synch with the reality

that Moore identified. “Hard-wired in our brain are linear expectations,

because that worked very well a thousand years ago, tracking an animal

in the wild,” he says. “Some people, though, can readily accept this

exponential perspective when you show them the evidence.” The other

element, he adds, is the courage required to act on that evidence.

Accepting Moore’s Law means understanding that what was once impossible

is now within our grasp — and leads to ideas that may seem on first

blush outlandish. So courage is required to resist that ridicule that

often comes from proposing such schemes.

For

the past few years, critics both in and out of Silicon Valley have been

griping about what I call the “Jetson Gap.” The critique is embodied in

venture capitalist Peter Thiel’s charge, “We were promised flying cars

and instead what we got was 140 characters.” But flying cars are rather

tame compared to the fantastic inventions we now use every day: a search

engine that answers our most challenging questions in less than a

second; a network of a billion people sharing personal news and pointers

to news and gossip; and a palmtop computer that among other things can

beam live video to the world and have a conversation with you.

Those

who understood Moore’s Law had the fortitude to make those advances.

And more people are catching on. A generation raised on Google thinking

is now working on new inventions, new systems, new business plans.

Businesses in virtually every sector are being challenged — and in some

cases shut down — by young entrepreneurs applying Moore’s Law. (Call it

the Uberization of everything.) It’s quite probable that on someone’s

drawing board right now is a project that will change our lives and earn

billions — but is a funding challenge because the pitch sounds, well,

crazy.

But as Page told me in 2102: “If you’re not doing some things that are crazy, you’re doing the wrong thing,”

Moore’s Law guarantees it.

This

article originally appeared in the Winter 2015 edition of Core, a

Computer History Museum publication. The issue is a special edition

commemorating the 50th anniversary of Moore’s Law.

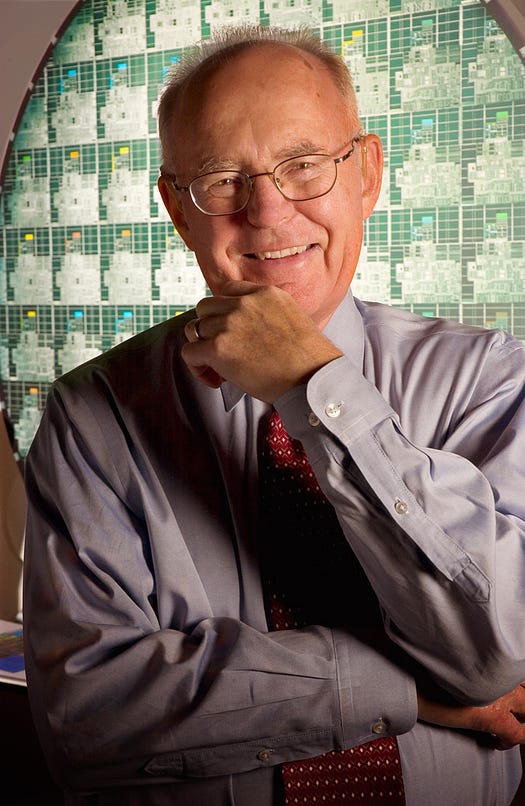

Notebook photo copyright Douglas Fairbairn Photography, courtesy of Computer History Museum. Moore photo courtesy of Intel.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Comentários são sempre bem-vindos, desde que se refiram ao objeto mesmo da postagem, de preferência identificados. Propagandas ou mensagens agressivas serão sumariamente eliminadas. Outras questões podem ser encaminhadas através de meu site (www.pralmeida.org). Formule seus comentários em linguagem concisa, objetiva, em um Português aceitável para os padrões da língua coloquial.

A confirmação manual dos comentários é necessária, tendo em vista o grande número de junks e spams recebidos.