O Imperador limpa o terreno...

PLA Purges! What does it all mean for Xi and Taiwan Risk?

“Surprising and a little bit worrisome for China...”

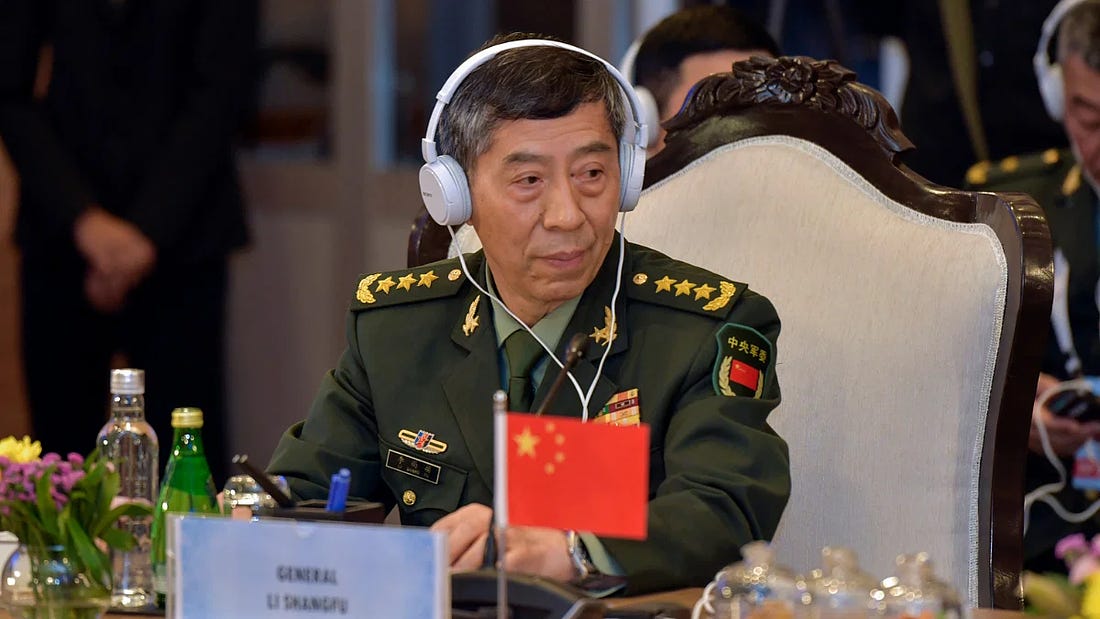

Yesterday Defense Minister Li Shangfu got officially purged. To discuss, we brought on Joel Wuthnow, a fellow at NDU. His research areas include Chinese foreign and security policy, Chinese military affairs, US-China relations, and strategic developments in East Asia. He joined ChinaTalk to discuss Xi Jinping’s recent purges of high-ranking members of the People’s Liberation Army, Xi’s larger vision for the PLA, and what all this internal turmoil might mean for China’s longer-term designs on Taiwan.

Key insights:

Over ten years after coming to power, Xi is still purging corruption from the military, reflecting his continued lack of trust in the PLA;

Corruption is historically endemic in the PLA in part because of its incentive structure, which makes graft a prerequisite for rising through the ranks;

Xi’s efforts to break up the PLA’s supervisory apparatus have only been partially successful (they’re still the same people even if they’re in a different department);

Amid the anti-corruption shakeup, China’s Rocket Force has been successfully developing hypersonic missiles, technology viewed as critical to countering US intervention in a regional conflict over Taiwan;

Despite Xi’s apparent distrust of his inner circle of military advisors, an echo chamber–induced invasion of Taiwan is still a live possibility.

Trust Issues in the PLA

Jordan Schneider: Xi Jinping’s got some trust issues. Over the past few months he’s run through a number of PLA generals he appointed less than twelve months ago! Joel, two-sentence overview: what has happened with these purges of late?

Joel Wuthnow: There have been many purges inside China, even beyond the PLA. Qin Gang 秦刚 disappeared, a whole bunch of people from the defense industry up and disappeared. In the PLA, a number of senior generals are missing in action; right now, frankly, we don’t know where they are. There are a lot of rumors circulating about these key figures, including the Defense Minister [Li Shangfu 李尚福] and the former commander of the Rocket Force [Li Yuchao 李玉超]. It’s not a good look for Xi Jinping.

The fact that there are so many people missing all at once means that Xi has a lack of trust and lack of confidence in some of his senior leadership right now.

Jordan Schneider: From the PLA watcher community, I had one friend reach out to me who said he was bummed about all this! He’s been following Li Shangfu for a decade, and all of a sudden he’s gone.

Are you excited or sad to see your friends leave the stage? What’s the emotional response when you see a new round of crackdowns?

Joel Wuthnow: For me, the feeling is surprise coupled with curiosity. It’s a shocking state of affairs, and the reason is this: us PLA watchers all mostly assume that Xi’s really in charge of the machine over there, that he put his people into place, and that his political rivals were gone a decade ago.

So it’s really surprising to wake up and find that the Defense Minister, someone who is probably pretty close to Xi — he’s on the Central Military Commission — is just gone. It’s surprising and a little bit worrisome, if you think about its implications for China.

Jordan Schneider: I think we should start by unpacking the idea that Xi has controlled or put his stamp on the PLA. To do that, we need to start with a little bit of institutional history. What was the bargain that Deng Xiaoping gave the PLA coming into the 1980s?

Joel Wuthnow: Back in the 1980s, the PLA was governing society. They were stacked in the Politburo. They were a very important part of the leadership and had a huge amount of power. Then Deng Xiaoping said, “No, we’re going to focus on reforming the economy. We want to bring in technocrats, and we want the military to be put in its place and put back in its barracks.” He said to the PLA, “We want you to modernize, but we’re not going to give you that much money to do it.”

It didn’t seem like a great bargain for the PLA. They had to give up a lot of authority and status without getting a lot of money. So, Deng said, “Okay, go back to your barracks — but you decide what you’re going to do. We’re not going to look into your affairs or get too involved in your business.”

So, Deng gave the PLA a huge amount of autonomy, and this was acceptable to them.

However, this also created a situation that allowed the PLA to become very corrupt and very inward-looking — very secretive and poorly supervised by the Politburo and the senior civilian leadership of the Party. This is really the origin of a lot of the problems that we’re seeing today.

China doesn’t have Western-style civil-military relations where there’s a lot of civilian oversight of the military — political appointees, courts, judges, media. There’s really none of that in China. So that’s the situation that the PLA found themselves in: corrupt and secretive, though not rebellious — they weren’t starting military coups against the leaders, as you saw in 1991 with the Soviet Union. But they weren’t fully professional and or fully “clean.” So the seed for what’s going on today was planted about forty years ago — in the 1980s — with Deng Xiaoping.

Jordan Schneider: The reason the PLA was so ingrained in society was because Mao decided that they were the only way to get the country out of the Cultural Revolution. So it was basically PLA power or complete chaos. This resulted in a very awkward situation where, if you’re in the PLA — if you’re not about to fight a war anytime soon and everyone else is getting rich around you — the dominant strategies if you want to rise up and be successful are to either do things like import luxury cars and run hotels; or to just graft on the procurement that’s been allocated to your budget instead of doing what the Premier wants (which is to get you in tip-top shape to potentially deter adversaries and maybe even fight an aggressive war).

So, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao: what did they want to do, and how did they struggle to execute their vision of what the PLA should be doing in the 1990s and 2000s?

Joel Wuthnow: Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao both basically wanted to make the PLA give up its business interests. The PLA was running all sorts of business empires as a way to make ends meet. Part of the way Jiang and Hu tried to undo this was by giving the PLA larger budgets; so in the 1990s and early 2000s, there were double-digit budget increases, as well as new rules and regulations.

A lot of the PLA’s operations, like the casinos and the luxury cars, were actually shut down — but this didn’t really change the basics: the PLA wasn’t well-governed or -supervised.

Jordan Schneider: To give folks a sense of just how broken the system was — there was not a way to rise up in the ranks without being corrupt? Because at a certain point you ended up having to buy your rank. All these positions had dollar amounts attached.

Say you want to get promoted and you don’t have a rich Chinese uncle that you can find to bankroll you. Who else might be interested in supporting folks getting promoted in the PLA system? Foreign intelligence agencies. So you end up with this very vicious cycle of the people who are getting promoted actually being the ones who are on the take from adversaries. This is the dynamic that Xi is facing as he comes to power in 2011 and 2012. Any other thoughts, Joel?

Joel Wuthnow: You’re right; it was really prolific, with schemes inside the general political department, which is like an HR system. Becoming a general had a renminbi 人民币 amount attached to it.

So when Xi comes to power in 2012, everybody who’s in the PLA is complicit in this system.

Xi’s dilemma was that he needed to fix the system, but couldn’t just get rid of everybody. So the top people on his list were those who were not only corrupt, but who were also associated with his political rivals. He focused first on Jiang Zemin’s people.

Jordan Schneider: So the hope was that you could scare people straight, while at the same time hopefully changing the institutional incentive such that everyone who may have had a dirty past ends up seeing the light, focusing on military national rejuvenation as opposed to making sure that their grandkids can have a beach house in Malibu, or what have you.

Joel Wuthnow: Exactly. But this isn’t to overstate or overplay the problem or imply that these guys are just sitting around doing corrupt schemes. Some of them are probably competent officers.

Reforming the PLA?

Jordan Schneider: So Xi starts off with a bang, throws a lot of folks out, including a lot of very senior folks, and then tries to build in some institutional reform so that this doesn’t happen again. At the same time he has a very ambitious vision for what he wants the PLA to achieve. So Joel, walk us through those two things: the reforms and his hopes for the PLA.

Joel Wuthnow: The reforms have many different pieces, some of which are about making the PLA a better warfighting organization, others of which are about making the PLA better managed. I’ll focus on the latter.

What Xi is trying to do is rearrange the system so that the people who are the supervisors — the internal control people — are a little bit disentangled from each other. Previously the General Political Department had all the power and was doing all the supervision. Corruption was investigated at that level. Xi Jinping broke up the General Political Department into a bunch of different components — financial auditors, anti-corruption people, military-court people. They’re all different from each other now; they don’t work for each other and are not part of the same bureaucracy.

These days, there are a few different control chains that come up independently to Xi Jinping’s level. He’s trying to eliminate corruption from that angle.

Ultimately, though, it’s a limited solution to the problem — because these are all still PLA officers. They all came up through the same corrupt system.

They’re all former GPD people, and they don’t work for each other anymore — but there’s no outside supervision or external control. So it is a reform that may make the system a bit better, but it doesn’t solve the fundamental problem, which is that the PLA is in its own little box.

Jordan Schneider: I assume another dynamic is that Xi has a very ambitious dream for the military power that China is able to project,which has led to 10% annual increases in the budget and, all of a sudden, a whole lot more money sloshing around than there ever has been in the history of this organization.

So the temptation is probably greater than it ever was in the Jiang and Hu eras, just because there’s so much more cash floating around.

Joel Wuthnow: There’s a lot of money sloshing around — the latest rumor is about the two guys from the Rocket Force [PLARF] who disappeared. That’s part of the PLA that’s undergoing a big expansion right now. They’re building silo fields; they’re building new ICBMs; they’re doing all sorts of construction there. The dominant rumor is that the entire leadership in the Rocket Force was in on some kind of scheme that’s not yet known, but it’s likely that there was so much money going into their strategic arsenal that the temptation was too great and the supervision was too limited and something got out of control, which led to Xi’s crackdown. But the details are totally opaque right now, and there are so many different rumors. It does seem to be about money.

Jordan Schneider: Can we get a two-second sidebar on what the Rocket Force is? It’s not something that most countries currently have.

Joel Wuthnow: It’s a little bit of a misnomer because they’re called the Rocket Force, but really this is the ICBMs, the land-based ballistic missiles. The Rocket Force runs most of the PLA’s nuclear arsenal for the PLA.

In addition to nuclear, they also manage the long-range conventional missile forces. You may have heard of the anti-ship ballistic missile or the DF26, the Guam killer. This is all part of the Rocket Force’s arsenal. It’s not so much rockets as it is ballistic missiles and cruise missiles.

Jordan Schneider: This is the really interesting internal contradiction here: on the one hand, something is wrong enough for Xi to want to fire these folks; but at least to outside observers, the Rocket Force has had some real technological successes. Can you talk a little bit about hypersonics and the broader development capabilities that the Rocket Force has presumably overseen?

Joel Wuthnow: The big thing with hypersonics is that it’s not like a ballistic missile. It’s a different trajectory. It’s not the speed — it’s that they’re very hard to track and intercept.

The reason why China is investing so much money in this is because it sees this technology as critical to countering US intervention in a regional conflict. China understands that we are reliant on large bases in the western Pacific, and they’re also aware that we’re building ballistic missile defenses.

It’s technologies like hypersonics that China thinks are an ace card, a game changer in terms of deterring, disrupting, and defeating us. Of course it’s also the case that the Chinese are just very, very good — historically and today — at missile forces and artillery and rocketry.

It’s operationally very significant and they’re good at it; hence, there’s a whole lot of money going into hypersonics.

Jordan Schneider: To that point, we’ve seen very impressive tests, which is at least a data point that the Rocket Force isn’t wasting and stealing everything that’s going through their coffers.

Joel Wuthnow: Right, it’s not that this money is going for naught. The question for Xi Jinping is: if they haven’t been honest about the spending, are they hiding something? So this gets to trust. Showing off in parades and a successful test here and there is one thing, but if the balloon ever goes up, will this huge arsenal be reliable? It’s not just the missiles that have to work — it’s the satellites and the people that are sitting at the controls.

Jordan Schneider: How much less likely are you to start a war involving very tricky joint operations if you don’t have a ton of confidence in your generals?

Joel Wuthnow: My view is that you probably don’t want to go down that path. Xi seems to have confidence in what they’re doing right now in terms of coercion: sending planes slightly across the midline, sending a bunch of planes up into the ADIZ and so on. The PLA is able to do that, but when talking about the requirements of a war, so much more is on the line for him and the Party.

If Xi has questions about whether things are going to work and his people are competent, then the incentive to go down the warpath starts to decline very quickly. I think this internal dynamic is something we don’t pay enough attention to on our side.

What’s This Mean for the PLA’s Future?

Jordan Schneider: You wrote recently that there’s tremendous pressure on the PLA to demonstrate progress and prove that it deserves the government’s largesse. We’re at a moment where China’s macroeconomic health over the next few years is very unclear. Do you think there’s any potential that Xi becomes so frustrated and fed up with his current PLA that he decides to starve the beast a little bit, given competing priorities and the clear lack of trust that exists between him and his military?

Joel Wuthnow: I don’t expect that he’s going to cut the PLA’s budget. Xi talks about security all the time. He seems to be rather paranoid.

For example, he needed to be talked down back in 2020 when he thought the US was going to attack him. In October 2020, the PLA leadership seemed to genuinely fear that the US was going to attack them as part of a so-called “October Surprise,” and they needed to be reassured. This was the big story with General Mark Milleyhaving to reassure his PLA counterpart.

This incident speaks to the larger issue of paranoia: Xi thinks the US is out to get him, that we’re doing color revolutions — which doesn’t match with trying to starve the beast.

The PLA is also not an insignificant political actor. I think they need to have some level of autonomy and attention from the top. Xi’s going to keep giving them funds, and he’s going to hope that they’re using them in the right way, but I think he does feel the need to continue to make examples out of people and show that he’s serious about these problems.

Nicholas Welch: When Xi came to power, he fired a whole bunch of people. And then during the recent Party Congress in October 2022, he stacked the Central Committee with loyalists. But now he’s firing people again. Do you think that this move makes him more or less likely to be influenced by a so-called echo chamber and to make rational decisions?

Joel Wuthnow: If you’re China, how do you get into a war? If you look at a pure cost-benefit analysis, I think the costs are very high and the benefits are not necessarily huge. But how else can you get into a war?

One possible way would be an echo chamber. Say the PLA is making a case to you as the boss: we’re ready. So Xi Jinping gave the PLA a 2027 deadline; they need to be ready to go to war with Taiwan by 2027. When that day comes, he’ll be asking the PLA, “What’s your update? I gave you time, I gave you money, I gave you a whole lot of inspirational talk — have you done it at this point?” And who’s going to come to him and say, “No, sorry, boss, we need another five years”?

So this is a concern — that the PLA lines up and says, “We’re ready, we think America is in decline, they’re a paper tiger, and Taiwan is having a lot of their own problems.”

If Xi Jinping comes to trust that and makes a decision based on false optimism — a bit like Putin being misled by his generals and invading Ukraine — it’s something worth worrying about.

That’s a different way of plunging into a war than just saying, “I’ve counted my missiles and counted their air defenses, and mine are superior” — that’s a clinical cost-benefit. This is more based on what you believe the outcome will be, regardless of how you’re actually going to perform. That echo chamber is worth worrying about.

Jordan Schneider: Doesn’t that echo chamber scenario seem pretty unlikely right now, as Xi is firing top leadership?

Joel Wuthnow: That’s basically right. If you had asked me the question a year ago, right after the Party Congress when the entire narrative was, “Xi has installed yes-men who aren’t going to give him candid advice and are going to tell him what they think he wants them to” — I would have given you a firmer answer on the overconfidence bit.

Now, given the shock of people disappearing and what that means in terms of his confidence, I’d say the chances are less than they were a year ago, less than they were two months ago — but not zero. That’s the reason to keep worrying. Five years from now, when Xi is seventy-five and he’s surrounded by people who may be giving him simple answers, we don’t know if there’s a 1 or 2 percent chance that he’ll believe them. To me, that’s still worth worrying about. What we’re really talking about is a 1 or 2 percent chance of calamity, so that’s still a pretty huge expected problem.