Temas de relações internacionais, de política externa e de diplomacia brasileira, com ênfase em políticas econômicas, em viagens, livros e cultura em geral. Um quilombo de resistência intelectual em defesa da racionalidade, da inteligência e das liberdades democráticas.

O que é este blog?

Este blog trata basicamente de ideias, se possível inteligentes, para pessoas inteligentes. Ele também se ocupa de ideias aplicadas à política, em especial à política econômica. Ele constitui uma tentativa de manter um pensamento crítico e independente sobre livros, sobre questões culturais em geral, focando numa discussão bem informada sobre temas de relações internacionais e de política externa do Brasil. Para meus livros e ensaios ver o website: www.pralmeida.org. Para a maior parte de meus textos, ver minha página na plataforma Academia.edu, link: https://itamaraty.academia.edu/PauloRobertodeAlmeida;

Meu Twitter: https://twitter.com/PauloAlmeida53

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/paulobooks

quarta-feira, 14 de junho de 2017

the world’s fastest-growing economies in 2017 - World Economic Forum

sábado, 30 de julho de 2016

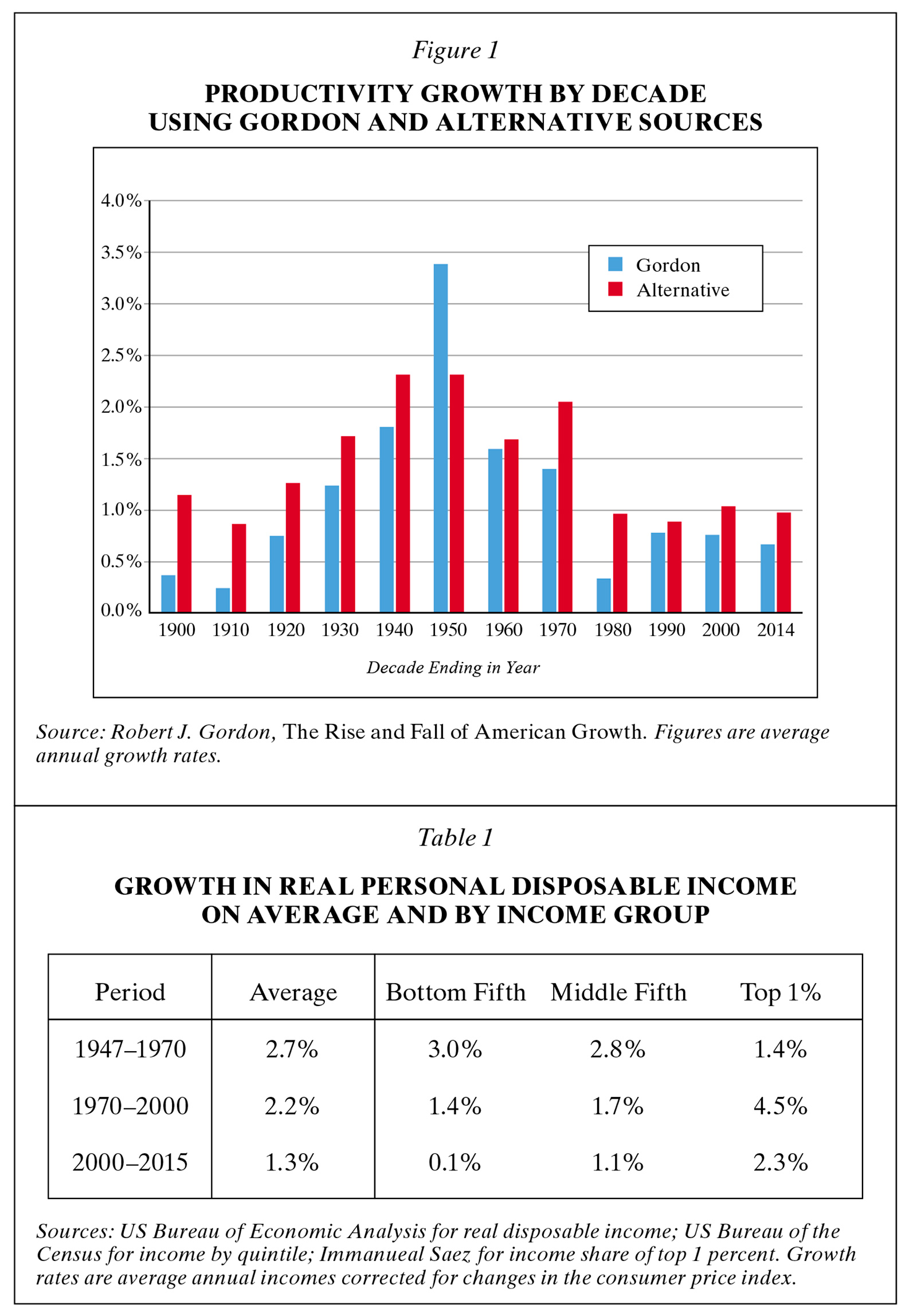

Gordon on Economic Growth in the USA, 1870-2014 - book review by William Nordhaus

Why Growth Will Fall

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living Since the Civil War

The century of revolution in the United States after the Civil War was economic, not political, freeing households from an unremitting daily grind of painful manual labor, household drudgery, darkness, isolation, and early death. Only one hundred years later, daily life had changed beyond recognition. Manual outdoor jobs were replaced by work in air-conditioned environments, housework was increasingly performed by electric appliances, darkness was replaced by light, and isolation was replaced not just by travel, but also by color television images bringing the world into the living room…. The economic revolution of 1870 to 1970 was unique in human history, unrepeatable because so many of its achievements could happen only once.

A consistent theme of this book is that the major inventions and their subsequent complementary innovations increased the quality of life far more than their contributions to market-produced GDP…. But no improvement matches the welfare benefits of the decline in mortality and increase in life expectancy….

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an “intelligence explosion,” and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.

- 1Productivity comes in several varieties. The simplest to measure is labor productivity, or output per hour worked. However, this does not account for improvements in education, or for changes in the access of the average worker to a larger stock of more productive capital. Total factor productivity (TFP) is a more complicated concept to measure than labor productivity because it involves measuring the contribution of capital and education, as well as determining how to weigh the different inputs, but today these are standard procedures.

A final detail is whether productivity relates to business output, to private output, or to total GDP (the latter also includes government output). Accurate measures are usually confined to business output because government output in such areas as education and military forces is difficult to measure and therefore these areas customarily are measured as inputs (teachers) rather than outputs (learning). Gordon generally uses the more comprehensive GDP because it is available for longer periods. It must be reemphasized that all productivity figures refer to measured output and omit the unmeasured contributions of important new and improved products discussed in Gordon’s main text. ↩ - 2The alternative is a splicing of the following sources: data for the early part is total factor productivity for the private economy (private GDP), 1890–1950, from Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition(Cambridge University Press, Vol. 3, Series Cg270, Cg278). The data are based on an early study by John Kendrick in Productivity Trends in the United States (Princeton University Press, 1967). These data are used for the TFP growth rates for 1890–1900 to 1940–1950. For the period 1948–2014, I use total factor productivity for the US private business sector from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. These are available at www.bls.gov/mfp/#tables, “Historical multifactor productivity measures (SIC 1948–1987 linked to NAICS 1987–2014).” These data are used for the TFP growth rates for 1950–1960 to 2000–2014. Note that for the two periods of overlap (1950–1960 and 1960–1970), the early (Kendrick) series and the BLS series are virtually identical. From 1948 to 1970, the private GDP TFP growth rate averaged 2.13 percent per year while the BLS series averaged 2.03 percent per year. ↩

- 3

Economic statisticians have developed techniques for incorporating external effects like pollution into the measurement of national output. The method is straightforward. You would begin with a measure of the physical emissions, such as annual carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions or sulfur dioxide emissions. These would be parallel to the production of new houses, currently included in the accounts. You then multiply the quantity by a “shadow price,” which would measure the social cost of the emissions. Again, the parallel here would be multiplying the quantity of new houses by the price of the houses. Since the emissions price is a damage, or negative price, the price times quantity of emissions would be subtracted from total output.

As an example, total CO2 emissions for the United States in 2015 were 5,270 million tons. The US government estimates that the social cost of emissions is $37 per ton (all in 2009 dollars). So the total subtraction is $37 x 5,270 = $195 billion. This would be a debit from the $16,200 billion of total output in that year, or slightly more than 1 percent of output. (These data are from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Energy Information Administration.)

Note, however, that CO2 emissions declined over the decade from 2005 to 2015, from 5,993 billion to 5,270 billion tons per year. So the subtraction from GDP to correct for CO2 emissions was smaller in 2015 than in 2005. Growth of corrected GDP was therefore a tiny bit higher after correcting for CO2 emissions than before the correction. To be precise, after correction, the real growth rates over the 2005–2015 period would be 1.394 percent per year using the corrected figures instead of 1.385 per year using the official figures.So correcting for CO2 emissions would lower the estimate of output, but would raise by a tiny amount the estimate of growth. ↩ - 4Studies on the impact of adding health to the national economic accounts include an early example from William Nordhaus, “The Health of Nations,” in Measuring the Gains from Medical Research: An Economic Approach, edited by Kevin Murphy and Robert Topel (University of Chicago Press, 2010). ↩

quinta-feira, 28 de julho de 2016

Um livro sobre os progressos economicos nos EUA, desde 1870, um modelo para o Brasil - Book review

Um modelo, talvez, de metodologia analítica para ser reproduzido aqui também.

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

Robert J. Gordon:

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016. vii + 762 pp. $40 (cloth), ISBN: 978-0-691-14772-7.

Reviewed for EH.Net by Robert A. Margo, Department of Economics, Boston University.

This is the age of blockbuster books in economics. By any metric, Robert Gordon’s new tome qualifies. It tackles a grand subject, the productivity slowdown, by placing the slowdown in the context of the historical evolution of the American standard of living. Gordon, who is the Stanley G. Harris Professor in the Social Sciences at Northwestern University, needs no introduction, having long been one of the most famous macroeconomists on planet Earth.

The Rise and Fall of American Growth is divided into three parts. Part One (chapters 2-9) examines various components of the standard of living, in levels and changes from 1870 to 1940. Part Two (chapters 10-15) does the same from 1940 to the present, maintaining the same relative order of topics (e.g. transportation appears after housing in both parts). Part Three (chapters 16-18) provides explanations and offers predictions up through 2040. There are brief interludes (“Entre’acte”) between parts, a Postscript, and a detailed Data Appendix.

Chapter 1 is an overview of the focus, approach, and structure of the book. Gordon’s focus is on the standard of living of American households from 1870 to the present. The approach is both quantitative — familiar to economists — and qualitative — familiar to historians. As already noted, the organization is symmetric — Part One considers the pre-World War II period, and Part Two, the post-war. The fundamental point of the book is that that some post-1970 slowdown in growth was inevitable, because so much of what was revolutionary about technology in the first half of the twentieth century was revolutionary only once.

Chapter 2 draws a bleak picture of the standard of living ca. 1870, the dawn of Robert Gordon’s modern America. From the standpoint of a household in 2016, conditions of life in 1870 would appear to be revolting. The diet was terrible and monotonous to boot; homemade clothing was ill-fitting and crudely made; transportation was dependent principally on the horse, which generated phenomenal amounts of waste; indoor plumbing was all but non-existent; rural Americans lived their lives largely in isolation of the wider world. In Gordon’s view, much of this is missing from conventional real GNP estimates. Chapter 3 continues the initial story, focusing on changes in food and clothing consumption. Gordon contends there was not much change in underlying quality but he argues that, by the 1920s, consumers were paying lower prices for food — having shifted to lower-priced sources (chain stores as opposed to country merchants) — and that most clothing was store-bought rather than homemade.

Chapter 4 studies housing quality. As with other consumer goods, housing also improved sharply in quality from 1870 to 1940. Gordon argues that much farm housing was poor in quality, while new urban housing was typically larger and more durably built. Indoor plumbing, appliances and, ultimately, electrification dramatically enhanced the quality of life while people were indoors. As elsewhere in the book, reference is made to hedonic estimates of the value of these improvements as revealed in higher rents. Chapter 5 details improvements in transportation between 1870 and 1940. These are grouped into three categories. The first is improvement in inter-city and inter-regional transportation in rail. This occurs chiefly through improvements in the density of lines and in the speed of transit. The second is intra-city which occurred with the adoption of the electric streetcar. The third, and most important arguably, is the internal combustion engine and its use in the automobile (and bus). Gordon especially highlights improvements in the quality of automobiles, noting that the car is not reflected in standard price indices until the middle of the Great Depression.

Chapter 6 details advances in communication from 1870 to 1940. By current standards, the relevant changes — the telegraph, telephone, the phonograph, and the radio — might not seem like much but from the point of view of a household in 1870, these technologies enabled Americans to dramatically reduce their isolation. As Gordon points out, one could phone a neighbor to see if she had a cup of sugar rather than visit in person, or listen to Enrico Caruso’s voice on the phonograph if it were not possible to hear him in concert. The radio brought millions of Americans into the national conversation, whether it was to hear one of Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats or listen to a baseball game. Chapter 7 discusses improvements in health and mortality from 1870 to 1940 which, according to Gordon, were unprecedented. After summarizing these, he turns to causes, chief among which are improved urban sanitation, clean water, and uncontaminated milk. Gordon also highlights improvements in medical knowledge, particularly the diffusion (and understanding) of the germ theory of disease. Chapter 8 studies changes in the quality of work from 1870 to 1940. These changes were wholly for the better, according to Gordon. Work became less dangerous, more interesting, and more rewarding in terms of real wages. Most importantly, there was less working per se, as weekly hours fell, freeing up time for leisure activity. There was a marked reduction in child labor, as children spent more of their time in school, particularly at older ages in high school. This was also the period leading up, as Claudia Goldin has told us, to the “Quiet Revolution” in the labor force participation of married women, which was to increase substantially after World War II. Credit and insurance, private and social, is the topic of Chapter 9. The ability to better smooth consumption and also insure against calamity are certainly improvements in living standards that are not captured by standard GNP price deflators. Initially the shift of households from rural to urban areas arguably coincided with a decrease in consumer credit but by the 1920s credit was on the rise due to several innovations previously documented by economic historians such as Martha Olney. Households were also better able to obtain insurance of various types (e.g. life, fire, automobile); in particular, loans against life insurance were frequently used as a source for a down payment on a house or car. Government contributed by expanding social insurance and other programs that helped reduced systemic risks.

Chapter 10 begins the second part of the book, which focuses on the period from 1940 to the present. As noted, the topic order of Part Two is the same as Part One, so Chapter 10 focuses on food, clothing, and shelter. Gordon considers the changes in quality in these dimensions of the standard of living to be less monumental than as occurred before World War II. For example, frozen food became a ubiquitous option after World War II but this change is far less important than the pre-1940 improvement in the milk supply. Quantitatively, perhaps the most important change was a reduction in relative food prices which, predictably, led to increase in the quantity demanded. Calories jumped, and so did obesity and many related health problems. For clothing, the chief difference is in the diversity of styles and, as with food, a sharp reduction in relative price holding quality constant. In Chapter 11 Gordon notes that automobiles continued to improve in quality after World War II, mostly in terms of amenities and gas mileage; and their usefulness as transportation improved with the building of the interstate highway system. Gordon is less sanguine about air transportation, arguing that quality of the travel experience deteriorated after deregulation which was not offset by reductions in relative prices. For housing, the major changes was suburbanization and a concomitant increase in square footage. The early postwar period witnessed some sharp improvements in the quality of basic household appliances, and somewhat later, the widespread diffusion of air conditioning and microwaves.

Chapter 12 focuses on media and entertainment post-1940. Certain older forms of entertainment gave way to television, the initial benefits of which were followed by steady improvements in the quality of transmission and reception. Similarly, there were sharp improvements in the various platforms for listening to music, with substantial advances in recording technology and delivery — the 78 gave way to the LP to the CD to music streaming and YouTube. The technology to deliver entertainment also delivered the news in ever greater quantity (quality is in the eye of the beholder, I suppose). Americans today are connected almost immediately to every part of the world, a level of communications unthinkable a century ago. A surprisingly brief Chapter 13, recounts the history of the modern computer. There is no way to tell this history without emphasizing just how unprecedented the improvements have been, from the very first post-war computers to today’s laptops and supercomputers. Moore’s Law, understandably, takes center stage, followed by the Internet and e-commerce. Gordon has a few negative things to say about the worldwide web, but the main act — why haven’t computers led a revolution in productivity — is saved for later in the book.

Chapter 14 continues the story of health improvements to the present day. As everyone knows, the U.S. health care system changed markedly after World War II, in terms of delivery of services, organization, and payment schemes. Great advances were made in cardiovascular care and treatment of infectious disease through the use of antibiotics. There were also advances in cancer treatment, mostly achieved by the 1970s; the subsequent “war” on cancer has not been as successful. Most of the benefits were achieved through diffusion of public health and expansion of health knowledge in the general public (e.g. the harmful effects of smoking). Since 1970 the health care system has shifted to more expensive, capital intensive treatments primarily provided in hospitals that have led to an inexorable growth in medical care’s share of GNP, increases that most scholars agree exceed any improvements in health outcomes. The chapter concludes with a mixed assessment of Obamacare. Chapter 15, on the labor force, is also rather short for its subject matter. Gordon recounts the major changes in the structure and composition of work since World War II. Again, it is a familiar tale — improved working conditions due to the shift towards the service sector and “indoor” jobs; rising labor force participation for married women; rising educational attainment, at least until recently; and the retirement revolution. Your faithful reviewer gets a shout-out in a brief discussion of the “Great Compression” of the 1940s; my collaborator in that work, Claudia Goldin (and her collaborator, Lawrence Katz) gets much more attention for her scholarly contributions on the subject matter of Chapter 15, understandably so.

Part Three addresses explanations for the time series pattern in the standard of living. Chapter 16 focuses on the first half of the twentieth century, which experienced a marked jump in total factor productivity (TFP) growth and the standard of living. Gordon considers several explanations, dismissing two prominent ones — education and urbanization — right out of the gate. In paeans to Paul David and Alex Field, he argues that the speed-up in TFP growth can be attributed to the eventual diffusion of key inventions of the “Second” industrial revolution, such as electricity; to the New Deal; and, finally, to World War II. Chapters 17 and 18 tackle the disappointing performance of TFP growth and the standard of living in the last several decades of U.S. economic history. Despite remarkable accomplishments in science and technology the impact on average living standards has been small, compared with the 1920-70 period. Rising inequality since 1970, which can be tied in part to skill-biased technical change, has made matters worse, as did the Great Recession. While Gordon is not all doom and gloom, he definitely falls on the pessimist side of the optimist-pessimist spectrum — his prediction for labor productivity growth over the 2015-40 period is 1.2 percent per year, a full third lower than the observed rate of growth from 1970 to 2014.

I think it is next to impossible to write a blockbuster economics book without it being a mixed bag in some way or other. Gordon’s is no exception. On the plus side, the book is well written, and one can only be in awe of Gordon’s mastery of the factual history of the American standard of living. We all know macroeconomists who dabble in the past. Gordon is no dabbler. One can find interesting ideas for future (professional-level) research in every chapter — graduate students in search of topics for second year or job market papers, take note. Many previous reviewers have chided Gordon for his pessimistic assessment of future prospects. Of course, no one knows the future, and that includes Gordon. It is certainly possible that he will be wrong about productivity growth over the next quarter-century — but I for one will be surprised if his prediction is off by, say, an order of magnitude.

I am less sanguine about the mixed qualitative-quantitative method of the book. I gave up reading the history-of-technology-as-written-by-historians-of-technology a long time ago because it was just one-damn-invention-after-another. At the end of a typical article recounting the history of improvements in, say, food processing, I was supposed to conclude that no amount of money would get me to travel back in the past before said improvements took place — except I never did reach this conclusion, knowing it to be fundamentally wrong. Despite references to hedonic estimation, TFP, and the like, in the end Gordon’s book reads very much like conventional history of technology. More than a half century ago Robert Fogel showed how one could quantify the social savings of a particular invention, thereby truly advancing scholarly knowledge of the treatment effects. Yet Railroads and American Economic Growth is not even cited in Gordon’s bibliography, let alone discussed in the text. If one’s focus is the aggregate, I suppose a Fogelian approach is impossible — there are too many inventions, and (presumably) an adding-up problem to boot. What exactly, though, do we learn from going back and forth between quantitative TFP and qualitative one-damn-invention-after-another? I’m not sure. There’s the rub, or rather, the tradeoff.

Criticisms aside, if you are into economics blockbusters, The Rise and Fall of American Growth belongs on your bookshelf, next to Piketty and the like. Just be sure it is a heavy-duty bookshelf.

Robert A. Margo’s Economic History Association presidential address, “Obama, Katrina, and the Persistence of Racial Inequality,” was published in the Journal of Economic History in June 2016.

Copyright (c) 2016 by EH.Net. All rights reserved. This work may be copied for non-profit educational uses if proper credit is given to the author and the list. For other permission, please contact the EH.Net Administrator (administrator@eh.net). Published by EH.Net (July 2016). All EH.Net reviews are archived at http://eh.net/book-reviews/

domingo, 3 de novembro de 2013

O baixo crescimento tornou-se a nova norma da economia mundial? - Cato Institute debate

Share Video