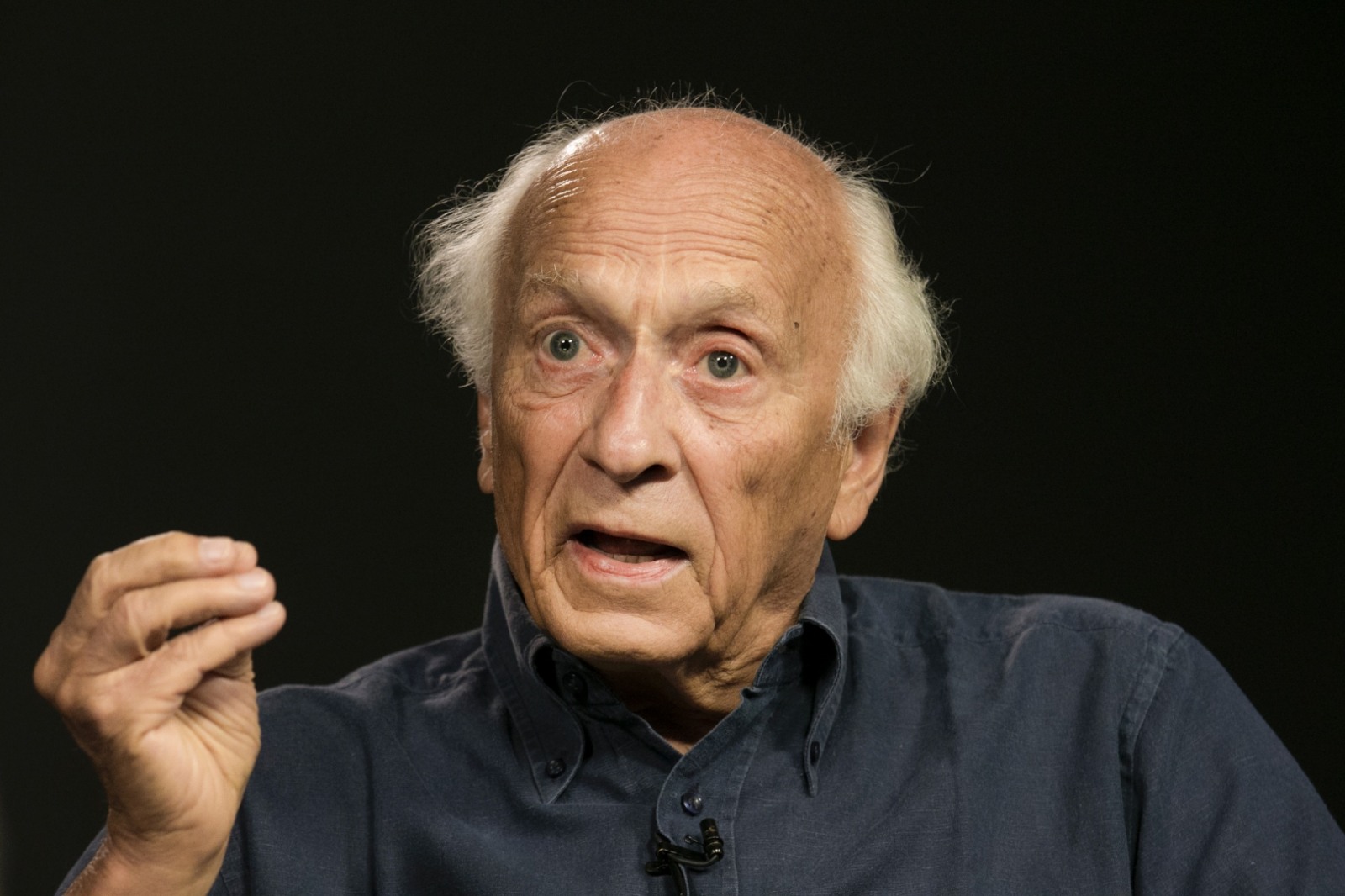

Autor do ensaio sobre Gusmão – que é considerado o “avô” da diplomacia brasileira –, Goes Filho também protestou. “Isso é censura, obscurantismo. Desse jeito, nenhum embaixador de prestígio vai poder publicar”, afirmou ele à Folha de S.Paulo. “É um assunto do século 18, e o autor foi vetado porque critica o ministro – não pelo que escreveu.”

Synesio Sampaio Goes Filho realizou neste livro em relação ao principal autor do Tratado de Madri o que havia feito para a formação das fronteiras do Brasil: tornou acessível ao leitor de hoje a compreensão de uma história que se convertera em algo de remoto e abstruso.Nem sempre fora assim. Até sessenta ou setenta anos atrás, a história diplomática do Brasil parecia às vezes dominada pela história das fronteiras. Na atmosfera de justa satisfação pela solução definitiva dos problemas territoriais do país levada a cabo pelo barão do Rio Branco, multiplicaram-se os estudos das questões fronteiriças, frequentemente escritos por diplomatas de carreira com vocação de historiadores.

Um dos mais produtivos entre esses autores, o embaixador Álvaro Teixeira Soares, resumiu com felicidade o sentimento que animava tais estudos. A solução sistemática dos problemas fronteiriços iniciada sob a monarquia e concluída por Rio Branco, escreveu Teixeira Soares, merecia ser considerada como uma das maiores obras diplomáticas realizadas por qualquer país em qualquer época. Não havia exagero em descrever desse modo o processo pacífico de negociação ou arbitragem pelo qual se resolveu metodicamente cada um dos problemas de limites com nada menos de onze vizinhos contíguos e heterogêneos (na época do Barão, o Equador ainda invocava direitos de fronteira com o Brasil, em disputa resolvida com o Peru somente muito mais tarde).

Passada a fase em que era moda escrever livros sobre fronteiras, o assunto perdeu grande parte do atrativo. Julgava-se que nada mais havia a dizer a respeito de problema já resolvido. Desconfiava-se de obras assinadas por funcionários diplomáticos, confundidas com a modalidade de publicações destinadas a engrandecer a própria instituição. Livros sobre discussões limítrofes, antes tão populares, tornaram-se difíceis de encontrar e mais difíceis de ler. O estilo envelhecera, os métodos da historiografia passada davam a impressão de obsoletos, a narrativa soava monótona, demasiado descritiva, apologética, pouco crítica, cansativa na enumeração de intermináveis acidentes geográficos.

Foi nesse panorama estagnado que Synesio teve a coragem de escolher para sua tese no Curso de Altos Estudos do Instituto Rio Branco em 1982 o tema enganosamente escondido sob o modesto título de Aspectos da ocupação da Amazônia: de Tordesilhas ao Tratado de Cooperação Amazônica . Lembro bem da surpresa positiva que causou a dissertação, pois fazia parte na época da banca examinadora do exame. Fui assim testemunha do surgimento de uma vocação singular de historiador voltado para recuperar a desgastada tradição de estudos fronteiriços.

Estimulado pela recomendação de publicação da banca, o autor ampliou e enriqueceu o trabalho, editado pelo Instituto de Pesquisa em Relações Internacionais (IPRI), em 1991, sob o título de Navegantes, Bandeirantes, Diplomatas: Um ensaio sobre a formação das fronteiras do Brasil. O livro teve o efeito de uma janela que se abria na atmosfera bolorenta da antiquada história das fronteiras, fazendo entrar o ar fresco da renovação modernizadora.

Redigida em linguagem límpida, objetiva, expressiva na sóbria elegância, a narrativa envolve o leitor em viagem sem esforço pela fascinante evolução do território brasileiro na sua fase de expansão, de avanços e recuos na Amazônia, no Extremo Oeste, na região da Bacia do Prata. Demonstra como se revelou constante em toda essa história a articulação do impulso pioneiro de exploradores, homens práticos determinados na busca de compensações materiais, com o trabalho cuidadoso de diplomatas e estadistas que legitimaram em instrumentos jurídicos o que não passava no início de ocupação precária de terras duvidosas.

Um dos méritos originais do livro consistiu em resolutamente colocar de lado a mitologia criada em torno de uma suposta linha que teria sido invariavelmente seguida por todos os governos brasileiros, refletindo uma doutrina inabalável ao longo dos séculos. Segundo tal linha de argumentação, desde os primórdios os políticos e diplomatas do Império teriam sustentado que o Tratado de Santo Ildefonso (1777) havia perdido a validez ao não ser explicitamente revalidado depois da fugaz Guerra das Laranjas (1801) no Tratado de Badajoz. Não existindo, portanto, direito escrito para definir as fronteiras, estas deveriam ser estabelecidas – seria o segundo postulado pretensamente imutável – de acordo com o princípio do uti possidetis , isto é, obedecendo à posse efetiva no terreno. O Tratado de Santo Ildefonso serviria apenas de maneira subsidiária para ajudar a dirimir dúvidas onde não se verificasse a ocorrência de posse ou não houvesse contradição entre o tratado e a posse.

O argumento apresentava alguma utilidade para comprovar a antiguidade e constância das pretensões brasileiras. Não passava, no entanto, de artifício de negociação, sem amparo real na realidade histórica. Synesio Sampaio Goes não se intimidou com a longa sequência de respeitados estadistas e estudiosos que haviam cercado essas afirmações com a proteção de sua autoridade e de seu prestígio. Mostrou com exemplos irrefutáveis que nenhum dos postulados havia sido verdade absoluta adotada em todos os casos. Não faltavam decisões e pareceres do Conselho de Estado advogando em favor da adoção de Santo Ildefonso como orientação para fixar fronteiras. Nem de episódios em que o Conselho ou o governo tinham recusado recorrer ao uti possidetis como critério para traçar limites.

Longe de enfraquecer a tradição brasileira em matéria de negociação de fronteiras, o trabalho de reconstituição da verdade efetuado pela obra conferiu historicidade e verossimilhança às doutrinas defendidas pelo Itamaraty, voltando a situá-las no contexto próprio do tempo em que foram definidas e no das circunstâncias que as modificaram. O desmonte da retórica apologética permitiu que aparecesse a verdade de uma evolução gradual, de tentativas e erros, de afirmação progressiva das teses mais convenientes. A narrativa fiel aos fatos fez emergir do passado uma diplomacia conscienciosa de estudo de mapas, de exploração de velhos arquivos, de construção paciente de doutrinas jurídicas adaptadas à situação de país cujos títulos originais a boa parte de seu futuro território eram pobres ou inexistentes. O resultado final, além de verdadeiro, valorizava em vez de empobrecer os méritos dos diplomatas que construíram a história do mapa do Brasil.

Na origem de toda essa história encontrava-se o alto funcionário da Corte portuguesa a quem se devia, mais que a qualquer outro, a definição do perfil territorial do Brasil, Alexandre de Gusmão. Brasílico, como se dizia na época, nascido obscuramente na humilde, insignificante Vila do Porto de Santos, tratava-se de personagem que atuara de modo discreto nos bastidores do poder. Permanecera quase anônimo por longo tempo, mais de um século, apesar de um ou outro estudioso mais arguto como o barão do Rio Branco ter reconhecido o papel que desempenhara.

Coube a um exilado político no Brasil do regime salazarista, o historiador português Jaime Cortesão, a tarefa de resgatar da penumbra da história a figura de Gusmão, desentranhando do silêncio dos arquivos os documentos que praticamente revelaram ao mundo a história real que se escondia por trás da negociação do Tratado de Madri (1750). Synesio Sampaio Goes, que já produzira o moderno clássico do estudo e da análise da história geral das fronteiras brasileiras, retrocede agora ao ponto de partida de onde tudo começou a fim de examinar como se chegou a pacientemente preparar a maior de todas as vitórias da diplomacia luso-brasileira na consolidação da expansão territorial do Brasil, o Tratado de Madri.

Conforme afirmei lá no início do prefácio, as duas realizações de Synesio, a da história completa, abrangente das fronteiras, e hoje a do Tratado de Madri e de seu autor mais importante, possuem uma característica definidora comum. Ambas reexaminam com olhar crítico o volumoso material existente, desbastam esse acervo daquilo que apresenta relevância menor para o leitor culto de nossos dias, reconstruindo com estilo contemporâneo, metodologia e linguagem atualizadas, narrativas que corriam o risco de não mais serem lidas a não ser por raríssimos especialistas.

Tome-se, por exemplo, o caso da obra magna de Jaime Cortesão, Alexandre de Gusmão e o Tratado de Madri, publicada nos anos 1950 pelo Instituto Rio Branco em nove alentados volumes com milhares de páginas de reprodução de documentos e mapas. Quem hoje em dia se disporia a ler a obra inteira? Mesmo a edição compacta em dois tomos restritos à vida e realizações de Alexandre de Gusmão, editada em 2016 pela Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão (Funag) e a Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo, estende-se por mais de oitocentas páginas de letra miúda, recheadas de longas discussões de erudição de interesse relativamente menor para o leitor médio.

Synesio não só torna a história dos limites e a de Alexandre de Gusmão acessíveis e atrativas aos leitores e estudiosos atuais. Ao modernizar e submeter a rigoroso crivo crítico tais narrativas, realiza obra original de mérito indiscutível. Ao discutir as hipóteses mais especulativas a respeito de incidentes da biografia de Gusmão, a autoria pessoal das instruções que orientaram o negociador português do Tratado, concepções intelectuais que teriam inspirado as ações lusitanas, o autor pesa com cuidado os argumentos e chega a conclusões que comandam o consenso pelo realismo, prudência historiográfica e bom senso.

Essas qualidades se destacam, entre outras passagens, nas que relativizam e moderam o entusiasmo raiando ao misticismo de Jaime Cortesão ao tratar de alguns mitos da história colonial como o da célebre “ilha Brasil”, a existência de um território delimitado de um lado pelo oceano Atlântico e no oeste por dois grandes rios que confluiriam para um mítica lagoa no interior das terras sul-americanas. A sobriedade nas avaliações e juízos confere veracidade digna de fé às afirmações amparadas, na falta de documentos conclusivos, por critérios de probabilidade e verossimilhança.

O autor faz bem de chamar ensaio biográfico o estudo da vida e ação de um personagem que viveu na primeira metade dos Setecentos. Faltariam elementos probatórios para tentar reconstruir a respeito da figura de Gusmão aspectos minuciosos da infância, da formação da personalidade na adolescência e juventude, das leituras e experiências definidoras como pretendem às vezes realizar exaustivas biografias de personalidades mais perto de nós. Uma técnica de narrar que funcionou de modo eficaz na construção da obra foi a de alternar o tempo todo a vida de Alexandre de Gusmão e a evolução dos acontecimentos que criariam as oportunidades para suas realizações. Basta passar os olhos pelo índice para perceber a dosagem alternada de matérias de contextualização — o Brasil, Portugal na época — com os capítulos biográficos — começos de vida, diplomata aprendiz, secretário real — voltando à colônia no apogeu do ouro, mas sem fronteiras, a relação do brasílico com sua distante pátria, os problemas do contrabando.

O estudo se revela particularmente útil no exame minucioso do que viria a ser presumivelmente a mais importante negociação territorial da história brasileira, culminando num tratado que de certa forma equivaleria a uma espécie de “escritura de propriedade” do território que forma o Brasil de hoje. Já se disse outras vezes e ressalta bastante deste livro a originalidade múltipla do Tratado de Madri. Num período em que quase todos os tratados de limites se originavam de guerras e refletiam a correlação de forças no campo de batalha, o acordo de 1750 foi exceção, negociado e concluído depois de longos anos de paz entre Portugal e Espanha.

Em contraste com a maioria dos inúmeros acordos limítrofes que o Brasil independente assinaria no futuro, o de Madri se salientou por desenhar a linha completa do mapa do Brasil ao longo de milhares de quilômetros de fronteiras terrestre. Não era o que desejavam os espanhóis, mais uma vez empenhados em somente limitar o ajuste a alguns setores de seu particular interesse, sobretudo na região da permuta da Colônia do Sacramento pelos Sete Povos das Missões do Alto Uruguai. Graças à firme insistência dos negociadores lusos é que se conseguiu definir o que, com ajustes relativamente menores, haveria de ser na prática o perfil territorial do Brasil moderno.

O Tratado de Madri tornou possível outra originalidade da história da formação territorial brasileira: a de que ela se encontrava virtualmente terminada antes da Independência. Em termos gerais, o chamado expansionismo, que foi a rigor muito mais português que brasileiro, alcançava quase seu limite máximo na véspera da Independência. Compare-se com a expansão norte-americana, que tem início a partir da Independência de 1776, para perceber a diferença das implicações que esse fato acarretaria para o relacionamento do país independente — Estados Unidos da América ou Brasil — com seus vizinhos igualmente independentes, México, no exemplo norte-americano, os dez vizinhos brasileiros, com o enorme contraste em termos de herança de ressentimentos históricos.

Vários dos estudiosos do Tratado de Madri fizeram questão de destacar que ele se adiantou a seu tempo na razoabilidade e no equilíbrio das concessões, no seu legado central, que consistiu em reconhecer de direito o que já ocorrera no terreno da prática: a supremacia da expansão luso-brasileira na Amazônia e no centro-oeste da América do Sul em câmbio do prevalecimento dos interesses castelhanos na Região da Bacia do Prata. Talvez se deva, em última instância, a esse espírito avançado em relação à época que o tratado tenha sido tão fugaz na duração formal: pouco mais de dez anos até a anulação pelo Tratado de El Pardo (1761).

Um dos enigmas da história luso-brasileira é entender por que o governo português, principal beneficiário dessa obra-prima de sua diplomacia, se converteu, em poucos anos, num dos mais ativos fatores de sua destruição. Os historiadores, entre eles Jaime Cortesão, alinham, é claro, argumentos e razões, que soam desproporcionalmente fracos para explicar erro tão grave de avaliação. Não é este o lugar para examinar a questão, de que procurei tratar em livro recente. De todo modo, o que conta é que, depois de vicissitudes e revezes sem conta perfeitamente possíveis de evitar, o espírito do Tratado de Madri acabaria por prevalecer. Esta constatação é seguramente a maior demonstração do gênio criador de Alexandre de Gusmão, capaz de sobreviver até à maligna inveja do marquês de Pombal, seu poderoso e overrated rival.

Em vida, Gusmão não alcançou recompensa nem reconhecimento pelo que fizera. Morreu no ostracismo, sem poder, com dificuldades financeiras. A Representação que dirigiu ao rei D. João V em fins de 1749, pouco antes do desaparecimento do monarca, ficou sem resposta. Permaneceria no limbo da história até meados do século XX, quando, graças a Jaime Cortesão, viu finalmente apreciada e valorizada sua contribuição com as seguintes palavras:

“Precursor da geopolítica americana; definidor de novos princípios jurídicos; mestre inexcedível da ciência e da arte diplomática, Alexandre de Gusmão tem direito a figurar na história como um construtor genial da nação brasileira, pela clarividência e firmeza de uma política de unidade geográfica e defesa da soberania, que antecipam, preparam e igualam a do Barão do Rio Branco”.

O primoroso ensaio biográfico que Synesio Sampaio Goes Filho dedica a sua memória reexamina, atualiza e ratifica, ponto por ponto, a justiça e exatidão do julgamento tardio da posteridade.