China Talk

Johanna Costigan is a writer based in New York. She regularly contributes to Asia Society, Trivium China, and Forbes.

Xi Jinping has charged Chinese Communist Party officials with the task of simultaneously suppressing and popularizing history. Fatal chapters of China’s history in living memory like the Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen should be largely buried — even as lessons learned from those eras continue to help shape Party ideology. (The major takeaway from the Cultural Revolution: keep the people involved; from Tiananmen: make them patriotic.) Other historical stories, like the lead-up to the CCP’s first National Congress in Shanghai and, decades later, China’s valorous efforts to defend itself against Japan during World War II, should be spotlighted. Their protagonists — heroes and martyrs — should be admired.

It’s up to rank-and-file cadres to bring these events into public consciousness through traditional means, such as education and tourism. But increasingly, they are also expected to use digital communication to transmit the Party-approved version of history to the people. The aim is not to stifle all discussions of history just because some less flattering, more factual episodes have to be sacrificed. Officials don’t want to make history a dirty word; on the contrary, they want to make it sexy. The goal: maximize Party history’s “attractiveness and infectiousness” 吸引力感染力.

Part of the impetus to popularize history is the fact that China’s economic growth can no longer match the rampant gains of previous decades. Even as China steps forcefully into its role as a global leader and innovation behemoth, the leadership can no longer rely on citizens’ financial gains to sustain loyalty, let alone genuine patriotism. History and identity are becoming imperative tools to instill pride and faith in the CCP’s century-long project to convince the people it deserves to lead them.

New regulations from the top suggest that Party leaders are increasingly willing to disrupt the previous status quo of defaulting to silence, including its more active form, censorship via deletion. Party history, they say, should not only be quietly edited to neutralize any threats to the leadership. It should also be clickable. People shouldn’t idly scroll past state-made social-media posts about history; they should swarm to them. That is a very tall order.

‘Public Secrecy’ and the Internet

Xi Jinping’s thinking on the power of the internet is clear. A recent People’s Daily article traces his guidance on buttressing and securing the internet and the information on it: “In today’s world, whoever masters the Internet will seize the initiative of the times” 当今世界,谁掌握了互联网,谁就把握住了时代主动权. According to the article, the Party must continue its efforts to master online discourse by publicizing its themes online “in a strong and colorful way” 浓墨重彩. And importantly, cadres — Party members — are obligated to fight “the ideological struggle on the Internet” 网络意识形态斗争.

Creating and sharing history-related writing and photos that break through the noise of the internet is particularly challenging in China. University of Oxford Professor Margaret Hillenbrand’s book, Negative Exposures: Knowing What Not to Know in Contemporary China, traces the Chinese public’s pursuit of self-preservation through engagement with “public secrecy” — the phenomenon of widespread and not always directly coerced self-silencing. It can come in the form of parents opting not to tell their children about traumatic historical events to keep them safe. Their memories of living through times such as Great Leap Forward 大跃进 or the Cultural Revolution — when acknowledging ongoing horrors would get someone in serious trouble — carry on, albeit diluted. China is still governed by the same party. What better than real ignorance to prevent the risk of awareness from carrying down to future generations?

The familial instinct to protect through suppression clashes with Xi’s history fixation. Netizens today need a hold on both what not to know and what toknow — despite receiving little formal education about the “sensitive” topics they should have “correct” understandings of. Sometimes total ignorance works best, but in other contexts, netizens, especially famous ones, might be better served by sharing the state’s version of the right idea. For most, this process is governed by trial and error. The negative version might occur through organic discussions on social media, when users encounter digital censorship of certain topics and opinions they might learn through the fact that they were censored are “incorrect.” The positive version is their exposure to media promotion of what is “correct.”

Regulating History

One useful subgenre for the CCP is its depiction of China’s “cultural heritage.” Composed of equal parts scrubbed history, human memory, and patriotic propaganda, cultural heritage is supposed to embody the episodes and artifacts from Chinese history that are most pertinent to its civilization — the material that carries identity, largely due to its longevity.

Online digital media has already become indispensable in promoting cultural heritage. But the Party says there is more work to be done. In a notice released in March, the National Cultural Heritage Administration 国家文物局 called for “the all-media dissemination of Chinese culture” 推进中华文化全媒体传播 and making “cultural relics and cultural heritage truly come alive” 让文物和文化遗产真正活起来. And just in case the stakes weren’t clear, the notice explicitly mentions them: “Cultural relics and cultural heritage carry the genes and blood of the Chinese nation” 文物和文化遗产承载着中华民族的基因和血脉.

The notice, which provides guidance to officials ahead of Cultural Heritage Day on June 8, also offers practical advice. It encourages the use of livestreams and other forms of publicity to “enhance the influence of the dissemination of Chinese culture” 增强中华文明传播力影响力. The goal is to attain “important public opinion support” for the new chapter of Chinese history, told in part through cultural relics 为谱写中国式现代化文物新篇章提供重要舆论支撑. The notice echoes the Government Work Report that came out of the Two Sessions meetings, which called for the “systematic protection and rational use” of cultural relics 加强文物系统性保护和合理利用.

Censorship alone does not cultivate “cultural heritage” or combat “historical nihilism.” The March notice seems to recognize that national pride runs on content, not its absence. And today, the most consumed content is digital — social-media campaigns and other multimedia displays could certainly help with this “all-media dissemination,” especially in a country with over a billion mobile phone users.

A month earlier, in February, the Central Committee released “Regulations on the Study and Education of Party History” 党史学习教育工作条例, elevating the importance of officials and the public grasping the “correct view” of Party history. They call for opposing and resisting historical nihilism, presumably through censorship and deletion. But they also call for making “official history the consensus of the whole party and the whole society” 让正史成为全党全社会的共识. That takes more than deletions; it requires creating and promoting digital content.

Indeed, the regulations encourage cadres to carry out commemorative events highlighting historical anniversaries and figures, especially martyrs (who are specifically protected under the Heroes and Martyrs Protection Law 英雄烈士保护法), and even to create online memorial halls. They also advise cadres to effectively use social-media platforms like Weibo and WeChat by making engaging content such as short videos.

Walking the New Tightrope

Sometimes, state narratives directly attempt to correct a strand of oppositional public opinion that, due to the CCPs’ censorship success, has passed its peak. For example, reproductions of and homages to Tank Man — the lone individual photographed during the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre who stood directly opposite a military tank — are scrubbed from the Chinese internet. But as Hillenbrand argues, that doesn’t mean the Party seeks a total erasure of Tank Man. That would be too blunt a force. Instead, now that enough time has passed that they can ensure success in its historical revisionism, authorities have tried to reclaim or “appropriate” the famous image — even if only subliminally.

Hillenbrand finds evidence of this impulse in the über-successful 2017 movie “Wolf Warrior 2” 战狼2, a film with a negligible plot but a clear message. China defeats America in a conflict, blowing up everything in sight along the way. At one point, a man stands directly opposite a tank; the resemblance is unmissable for anyone equipped to spot it. Hillenbrand describes “the patriotic snatching back of this most global icon of civic dissent” as evidence that the stubborn cropping up of Tank Man images has caught the Party’s attention and made officials nervous. It has also made them “determined to claim him as its own.” If Tank Man is going to continue to exist — to any extent — among Chinese people, authorities will respond by trying to secure him under their control, even if it means drawing more scrutiny to him than the occasional historically accurate post ever could.

“Public secrecy about Tank Man and Tiananmen,” she writes, “has effectively drawn the authorities into another zero-sum game in which the state itself is now disrupting the faux tranquility of a hushed past.” And the latest regulations on cultural heritage and history education suggest that Party officials appear willing to disrupt that tranquility, if there is a chance of payoff.

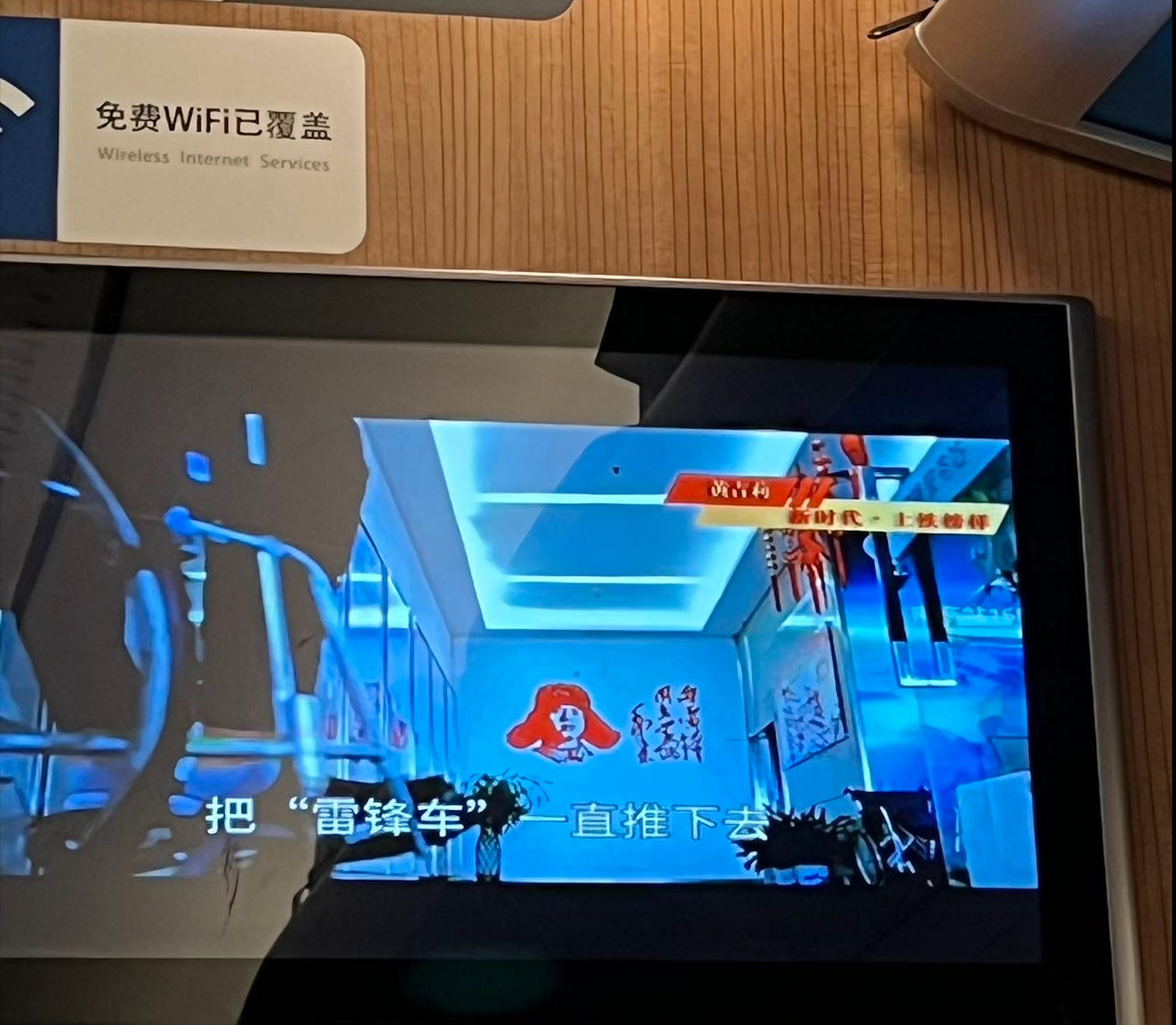

For example, beginning under Deng Xiaoping, the CCP leadership intentionally dulled the ultra-red tone, hysteria, and, to a degree, memory of the Mao era. Now, however, one of its most famous icons, the solider Lei Feng 雷锋, has reached digital prominence. Lei has been touted as a hero for decades, but today he can be spotted in propaganda on public screens in Beijing and Shanghai. Two years ago on Lei Feng Day (March 5), one postthat went viral encouraged readers to “carry forward the spirit of Lei Feng and write his story in the new era” 让我们一起弘扬雷锋精神,书写新时代雷锋故事.

Mass censorship is an impressive feat for which the CCP is famous, evidenced by its Great Firewall. But making benign versions of history go as close to viral as possible — without soliciting or encountering public commentary that steps over the Party’s red lines — will probably be even more difficult than the Party’s systematized efforts to keep the Chinese internet squeaky clean. It’s one thing to write regulations on teaching and policing Chinese history; it’s another to actually implement them.

History’s utility outweighs its precarity to the Party. Beijing has cultivated an environment where you can cross over a red line by saying something or nothing. But at the same time, it’s not enough to stay silent on “sensitive” issues; ideal citizens also zealously share the safe subjects, adopting and posting state-approved analyses.

Even as the Party attempts to co-opt China’s cultural heritage, grassroots representations of the country’s history and culture persist. They have limited lifespans and constrained reach, but the Party has not succeeded in wiping them out entirely (doing so might arguably have never been the objective). Members of the public continue to push back against increasingly dictatorial depictions of China’s past. Pseudonymous author Fang Fang 方方 wrote what amounts to an unofficial history of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. The filmmaker and activist Ai Xiaoming 艾晓明 has produced documentaries detailing corruption and political prisons and China. And everyday people still share their original interpretations of history on social media platforms like Douban 豆瓣. Their efforts have staying power, even if their posts do not.

In what Hillenbrand describes as “environments where secrecy is ambient and at large,” cultural manifestations created by the people “generate a communality — even when their audiences are small — that can be capacious enough to stage a reckoning with the things that society professes not to know.” Such a reckoning may or may not occur anytime soon. But China is certainly overdue for one.