Bem, continuando a fazer o tour do nosso fantasma, este acadêmico americano, que leva a coisa a sério, traça a anatomia do bloco movido a petrodólares chavistas...

A Guide to ALBA

by Joel D. Hirst

Americas Quaerterly (

link)

What is the Bolivarian Alternative to the Americas and What Does It Do?

“…all who served the revolution have plowed the sea.”

Simón Bolívar, 1830

A little over a year after taking office under his new Bolivarian Constitution, at a conference of Caribbean states on the Island of Margarita in 2001, President Hugo Chávez announced his intention to follow through on Bolívar’s political dream of creating an integrated nation-state in South America. “We from Caracas continue promoting the Bolivarian idea of achieving the political integration of our states and our republics. A Confederation of Latin American and Caribbean states, why not?"1 After several years of domestic instability, on December 14, 2004, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez and Cuban President Fidel Castro signed into law the creation of the Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América – Tratado de Comercio de los Pueblos (Bolivarian Alternative of the Americas—ALBA).

To understand the nature of the Bolivarian Alliance of the Americas (ALBA) we must travel back to the dawn of South American independence. It is there, in the grand visions and hard-fought battles of South America’s founding fathers, that we find the seed of the ALBA. It grew from the idea of Simón Bolívar to establish Gran Colombia from what today are Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador. In this, Bolívar envisioned one powerful Latin American nation, subordinate to the will of one maximum caudillo and steadfast in its opposition to the United States. It was, Bolívar believed, the only way South America would be able to stand up and prosper in the face of what he could see, even at that early moment, would be a powerful giant and rival to the north. In a last-ditch effort to save his political project, Bolívar assumed the role of dictator over the unruly body, resigning a short time later—living long enough only to see the Gran Colombia and the Congress of Panama collapse.

Yet almost two hundred years after Bolívar’s death and since the great post-independence wars shattered his grand vision, his words and ideas still reverberate around an exhausted continent. And again they have bred disorder under the imperial ambitions of another powerful, controversial Venezuelan leader.

GROWTH

Since its founding in Cuba in 2004, ALBA has grown from two to eight members with three observer countries: Haiti, Iran and Syria. Honduras briefly became a member under President Manuel Zelaya, but after the June 2009 coup d’état, the de facto government withdrew. Despite the growth, ALBA represents only a small fraction of the Latin America and Caribbean region’s economic share, population and land mass.

Current Members

IDEAS

There are three overarching ideas that guide the ALBA:

1) Conflict—ALBA seeks to institutionalize radical conflict (internal and external) which its member countries believe is necessary to rebuild “Gran Colombia”.2 According to Fernando Bossi, former president of the Bolivarian Congress of the Nations and member of the ALBA Social Movements (the operationalization of the Forum of São Paulo whose members serve as the “foot soldiers” of the ALBA), the alliance is the next phase of the “ancient and permanent confrontation between the Latin American and Caribbean peoples and imperialism.”3 In this new phase, countries are required to choose sides, between the ALBA and socialism or the United States and free market capitalism.4 This conflict has seen itself expressed in the almost constant conflagrations such as the police protest in Ecuador, the ongoing violence and political turmoil in Venezuela and the regional violence in Bolivia. Internationally, this has meant conflicts between neighbors such as Ecuador and Venezuela with Colombia, Venezuela with most neighbors (at one moment or another), Nicaragua with Costa Rica, and all of them with the United States.

2) 21st Century Socialism—The economic model espoused by ALBA member states is based loosely on a Trotskyite version of communism outlined by the Mexican academic Heinz Dieterich (who literally wrote the book on 21st Century Socialism). The model includes the now famous, “participatory and protagonist democracy” which involves the eventual elimination of representative democracy—and its institutional and civil-rights based approach to governance—in favor of local participation linked to a strong caudillo executive. In Venezuela this is done through the Popular Power, which establishes communes at the local level that report directly to President Chávez. In Nicaragua it is the Citizen Power, local committees organized and reporting to Rosario Murillo, President Ortega’s wife. Similar mechanisms exist in Cuba with the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (but without the popular participation evidenced in other ALBA countries). In Bolivia this is done at the grass roots through empowering local indigenous organizations. This non-institutional approach to governance increases executive power. Not coincidentally, the constitutional reforms in Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela, and now in Nicaragua have extended presidential mandates and authority. As Luisa Estela Morales, President of Venezuela’s Supreme Court stated in 2009, “We cannot continue to think about the separation of powers because it is a principle which weakens the state.”

3) International Revolution—ALBA is largely a regional infrastructure designed to support the radical revolutionary processes inside member countries. As Bossi stated, “ALBA is one chapter of a global revolution.” This has brought ALBA member countries into contact and cooperation with other revolutionaries the world over—the principal of these being Iran but also including Hezbollah, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias Colombianas (FARC), the Spanish Basque terrorist group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA), and the Colombian Ejercito de Liberación Nacional (ELN) among others. The purpose of this international revolution is, as President Chávez has stated, “the creation of a new world order.” According to ALBA foreign policy, the current institutional order must be brought to its knees in order to allow a new “multi-polar world” to emerge. Essential to this is the collapse of the United States as a global superpower.

COMPETING VISIONS: FTAA VERSUS ALBA

From the very beginning of his presidency, Chávez devised the Bolivarian Alliance as the ultimate expression of his foreign policy. The “alternative” was initially planned as a substitute to the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA)—a plan developed by the administration of U.S. President Bill Clinton to create a free trade zone from Canada to Argentina—and to combat western style economic integration with a new economic and political model: 21st Century Socialism.5 Consistent with the changing nature of Latin American politics, the “alternative” has rapidly morphed to reflect the realities of the region and its member countries into a flexible ideological alliance.

Comparing and Contrasting on the Issues

ACTIVITIES

Operationally, the ALBA has expanded the undertaking of “Grand-National Projects,” social projects implemented between two or more member states. These state-run endeavors are operated by state-to-state Grand-National Companies (created in opposition to transnational companies). Currently there are twelve grand-national projects in various stages of development (most with corresponding companies).

The projects themselves are being developed with varying degrees of success. The education program, with support from Cuba’s Sí, Se Puede (“Yes We Can”) literacy program has reduced illiteracy across the region. Nicaragua has implemented the Programa Hambre Cero (Zero Hunger Program) to reduce global acute malnutrition by up to 4 percent. The telecommunications project has purchased a Chinese satellite, has run a fiber-optic cable between Cuba and Venezuela (and eventually Jamaica and Nicaragua) and has established dozens of TV stations (including TeleSUR, the ALBA’s international news channel) as well as wire services for facilitation of documentaries, videos, movies, interviews and news. For its culture activities, ALBA has organized literary fairs, fellowships, literature prizes, movie showings, and has even held Olympic style games in Havana on three different occasions (every other year). And ALBA health has facilitated millions of consultations, operations and visits by Cuba-trained community health workers. Some programs are atrophied due to mismanagement, such as ALBA agriculture. Still others exist only in name. While ALBA claims to centrally plan these activities, more often than not they arise spontaneously from the recommendations of social movements6 or member states and are subsequently brought within the overarching framework of the ALBA’s integrationist imperatives.7 President Chávez uses Venezuela’s windfall oil profits to fund these projects and significant logistical support and knowhow for the implementation of the ALBA infrastructure comes from the well trained agents of the Cuban government.

Grand National Projects

THE BANK OF ALBA AND FUNDING

To fund these projects, the ALBA has created a Bank with offices in Venezuela and Cuba, and an initial $1 billion in resources, as well as a regional trade currency called the Sistema Único de Compensación Regional or SUCRE. “Enough with the dictatorship of the dollar, long live the SUCRE” said President Chávez in 2009 upon approving the legislation that established the SUCRE. The SUCRE entered into use a year later and is used for government-to-government exchanges.

Currently pegged at $1.25 per one SUCRE, the value of the SUCRE will eventually float based on a basket of member country currencies (the bank and SUCRE will serve to house member countries currency reserves). The Bank of ALBA has its offices in Caracas and its president, Nicolas Maduro, is also currently Venezuela’s Foreign Minister.

Beyond funding from the ALBA Bank, financial support for projects has come through Petro-Caribe and the Petro-Caribe Fund¬—an energy agreement linking Caribbean and Central American nations to Venezuelan’s energy infrastructure and reserves. This organization serves as a gateway organization to the ALBA.

In addition, Venezuela has provided substantial off-budget financial support. Due to the mercurial nature of Venezuela’s financial management, a full accounting of Chávez’ support for the ALBA may never be known. However, analysis by the Centro de Investigaciones Económicas (CIECA), a Venezuelan think tank, and by the intelligence unit of Venezuelan political party Primero Justicia, has put the gifts at above $30 billion. By the Venezuelan government’s own public reports, preferential oil deals alone have cost as much as $20 billion over the last five years.

The ALBA Economies

POLITICS

Politically, the ALBA has been extraordinarily active. Only in their first six years of existence, they have held sixteen ordinary and extraordinary summits. At each of these summits, agreements for projects and cooperation are reached and ALBA continues to take shape and direction.

ALBA members use their regular summits to define ALBA positions within international organizations where they usually vote as a block. Through their powerful lobby and financial largesse, they have assumed marginal political control over the Organization of American States (OAS). This has allowed them to deflect accusations of violations to the Inter-American Democratic Charter. They have also participated in international events with some success, including congealing the effort against the Copenhagen climate accords in 2009.

Summit Breakdown

Finally, there is a nascent military component to the ALBA. During the 7th ALBA Summit in Bolivia in 2009 there was discussion of a mutual defense pact, though it was never officially ratified in the summit’s declaration. At the Summit, Bolivian President Evo Morales stated boldly, “The proposal of my government will be to approve a Regional Defense School with our own doctrine.” Despite the lack of ratification, ALBA has quietly moved toward implementation of this idea establishing the Regional Defense School in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. The military has always had an important role in President Chávez’ political project—something the Bolivarian president has expressed as the “civic-military” alliance.

The defense theory emerges from the writings of Spanish radical philosopher Jorge Verstrynge. In his book “Peripheral War and Revolutionary Islam”—which President Chávez distributed to all members of the Venezuelan army, Verstrynge lays out the doctrine of asymmetric warfare, as practiced by Islamic insurgents over the years. This, according to President Chávez and his military, is the only technique by which ALBA will be able to withstand what they are convinced will be an inevitable attack from the United States.

President Chávez and his ALBA followers are betting their collective futures on the creation of a resource wealthy, energy-rich, revolutionary South American bloc in which their stated desire is to disrupt the international order and facilitate the creation of a “new world order”—and use the ensuing chaos to rebuild Bolívar’s vision of a Gran Colombia. Will this new expression of Bolívar’s Latin American revolution may be better plowed with an oil tanker?

Joel D. Hirst is an International Affairs Fellow in Residence at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Endnotes

1. Hugo Chávez, III Conference of Caribbean States, 2001.

2. United Nations University – Comparative Regional Integration Studies, Working Paper W/2008-4, p33.

3. Cuadernos de Emancipacion, N35, ISSN 0328-0179, Fernando Bossi, p21.

4. Cronica de una Crisis Anunciada – FLACSO, p7.

5. Cronica de una Crisis Anunciada – FLACSO, p6.

6. Construyendo el ALBA: Nuestro Norte es el Sur, Rafael Correa May 2005

7. United Nations University – Comparative Regional Integration Studies, Working Paper W/2008-4, p33.

8. Foreign Affairs LatinoAmerica, Volumen 10, Numero 3, Julio-Septiembre 2010. Josette Altmann, p3.

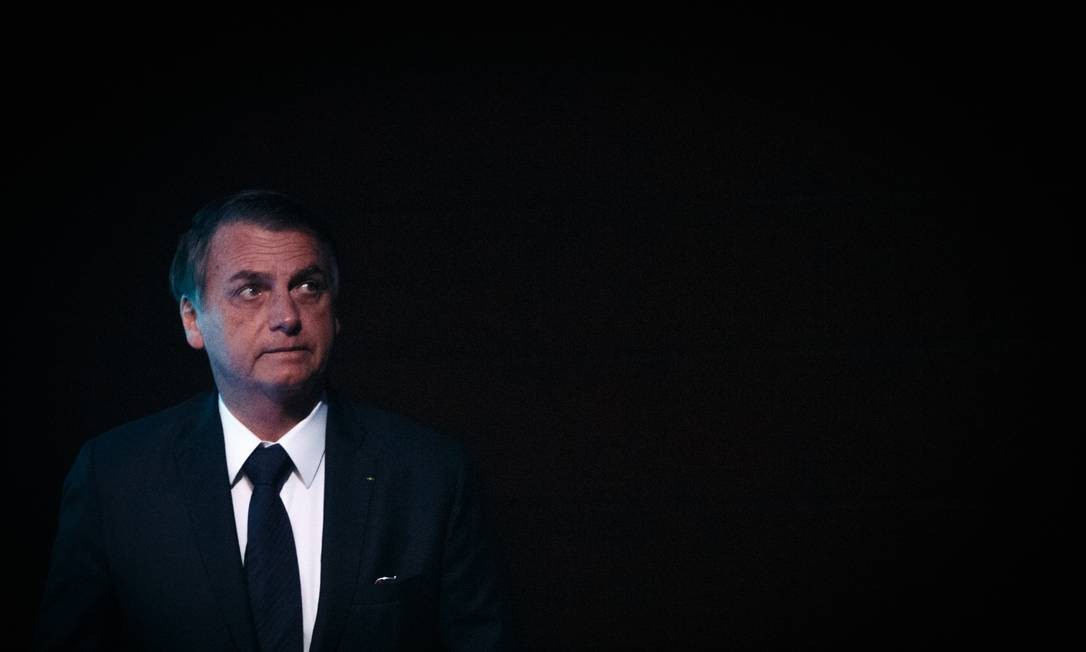

General Santos Cruz attends an event with President Bolsonaro before his departure from the administration.

General Santos Cruz attends an event with President Bolsonaro before his departure from the administration. General Santos Cruz attends an event with President Bolsonaro before his departure from the administration.

General Santos Cruz attends an event with President Bolsonaro before his departure from the administration.