What Marco Rubio Has Said About Latin America

President-elect Donald Trump has nominated Florida Senator Marco Rubio for Secretary of State, making him potentially the first Latino to hold the position. The three-term senator, a son of Cuban immigrants, was born in Miami and was highly influential on Latin America policy during Trump’s first administration.

That influence is now likely to grow. He has consistently spoken out against dictatorships in Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua. He has also criticized some of Latin America’s leftist leaders for their positions on Venezuela and China’s presence in the region.

Here is a selection of some of Rubio’s recent statements on Latin America.

On Latin America

April 2024

Article in The National Interest:

“We must take seriously the opportunities for collaboration presented by countries like Ecuador, El Salvador, Argentina, Paraguay, the Dominican Republic, Peru, Guyana, and Costa Rica.”

“Our region is currently experiencing at least six major crises. These range from unprecedented mass migration at the U.S. southern border to the complete breakdown of social order in Haiti to ramped-up state oppression in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. At the same time, the outlook for our region remains bright.”

“Is this a contradiction? Only if we ignore the bright spots in Latin America and the Caribbean. Even as we recognize the horrors occurring not far from our shores—and do our best to counter them—we must draw inspiration from the new generation of potentially pro-America leaders in the Western Hemisphere.”

On Cuba

August 2024

Introducing a resolution in the Senate condemning the Cuban government:

“The world is bearing witness to the multiple ways the Castro/Díaz-Canel regime has served as a puppet for Communist China, Iran, and most recently Russia. America has a moral duty to defend our nation’s interests and we must continue to uphold democratic order and justice in our hemisphere.”

April 2024

Interview in Voz:

“Cuba has a long history of intelligence and military cooperation with the communist government of China…. In many cases, we have not done enough to create alternatives to what China has done in many countries.”

On Venezuela

August 2024

Op-ed in the Miami Herald:

“The Biden-Harris administration has “serious concerns” that dictator Nicolás Maduro’s announcement of electoral victory in the recent presidential election “does not reflect the will or the votes of the Venezuelan people.”

“But such an outcome to this sham election was entirely predictable from the start. It was made more so by three years’ worth of concessions to and negotiations with the Maduro narco-dictatorship.”

“In short, the Biden-Harris Administration gave away every ounce of leverage we had over Maduro, then appeared surprised when he didn’t do what they wanted. It’s problematic to say the least, and not just for the people of Venezuela—or for opposition leader María Corina Machado and presidential candidate Edmundo González, who are now facing threats of imprisonment—but for America.”

“In recent years, nearly eight million Venezuelans have fled their country. Many of them have crossed our southern border, and many more will do the same if Maduro retains power.”

“The tyrant will also happily send dangerous criminals—like the brutal Tren de Aragua gang, which is already wreaking havoc on our streets—the United States’ way. None of this makes life easier for American communities. It shows the White House’s feckless policies have failed across the board.”

January 2019

Comments for CNN regarding Venezuela:

“I don’t know of anyone who is calling for a military intervention.”

September 2018

Quote in Newsweek:

In an interview with Univision 23, Rubio said he would not rule out the military option in Venezuela. Rubio, a vocal opponent of Maduro’s regime, commented in Spanish and was quoted by Newsweek.

“For months and years, I wanted the solution in Venezuela to be a non-military and peaceful solution, simply to restore democracy.”

“I believe that the Armed Forces of the United States are only used in the event of a threat to national security. I believe that there is a very strong argument that can be made at this time that Venezuela and the Maduro regime has become a threat to the region and even to the United States.”

On Mexico

May 2023

Interview in El Universal:

“Mexico is an important partner of the United States. The country, its institutions. But López Obrador is not a good ally. The current president, unfortunately, is dedicated to talking nonsense, to interfering in U.S. policy. His thinking is beyond the left, a strange thinking in terms of that line with all these dictators in the hemisphere. And he has a domestic policy with which he has handed over a large part of his national territory to the drug traffickers who control those areas. That matters to us because we are seeing the consequences of that violence, that criminality entering our border and our country. So I have my disagreement with him, but he is the president of Mexico today, he was not yesterday and he is not going to be tomorrow. There is a difference between the country and the importance of the country and its institutions and whoever is in office at the moment.”

Interviewer: “Would you agree with sending U.S. troops to combat drug cartels in Mexico?”

“Well, as long as there is cooperation from the Mexican government, which at the moment I don’t think we are going to see, because this is a president who came into office saying that he didn’t want to go after these criminal gangs. I would be willing to support this measure, but it has to be in coordination with the armed forces and the Mexican police force. Otherwise, it would not be possible to do it.”

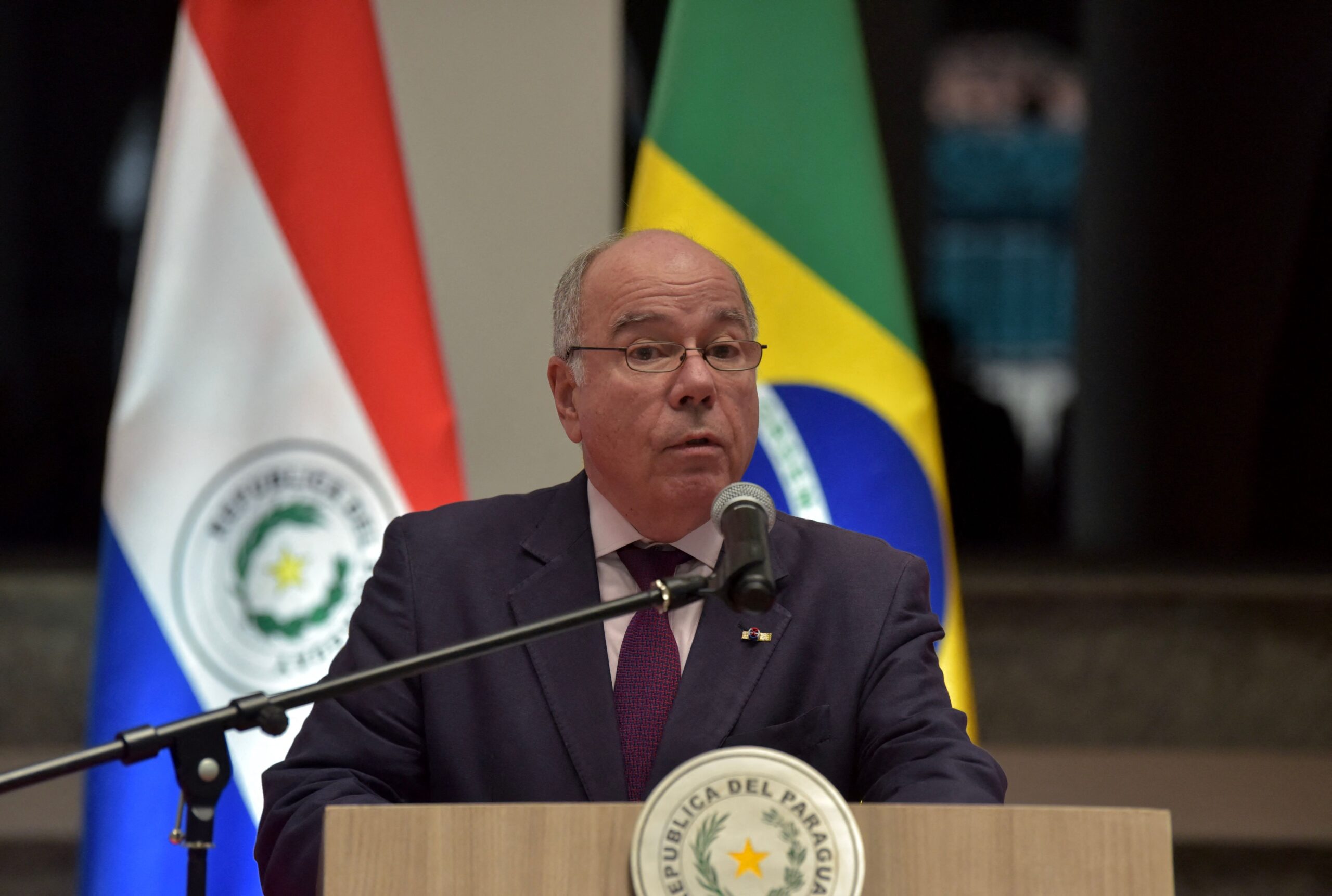

On Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva

May 2023

X post commenting on a Reuters piecereporting on Lula’s critiques of U.S. sanctions on Venezuela:

“Brazil’s Lula da Silva is the latest far-left leader who whitewashes the criminal nature of the Maduro narco-regime, days after meeting with Pres. Biden. Under the Biden Administration’s weak foreign policy, tyrants in our region feel emboldened to seek international support.”

February 2023

Op-ed in The Epoch Times:

“It sounds paradoxical, but President Lula da Silva of Brazil is seeking closer ties with both the United States and Communist China…. For now, that means he will take what he can get from both the U.S. and the CCP—so long as it benefits his agenda.”

“President Biden must take a firm line with Brazil’s new president, holding Lula to account for his friendliness toward the CCP—as well as other bloody handed dictatorships, like those of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.”

On Colombian President Gustavo Petro

April 2023

Interview in Semana:

“It is very dangerous that the president of a country, which for years has been a great ally of the United States, now chooses to be the spokesperson for a criminal drug dictatorship like the one in Venezuela. In order to obtain the support of intermediaries like Maduro and Castro for “negotiations” with the ELN terrorists, Petro is willing to lobby for a vile dictatorship.”

April 2023

In Medium:

“For decades, Colombia has been ravaged by the violent outbursts of rebel groups like the National Liberation Army (ELN)…. Over the past few months, Petro has sought to end the violence through negotiations…, but he’s only sowing disaster.…”

“Case in point: the ELN continues to attack the Colombian government…. These are the mercenaries Petro wants to appease, even to the point of backtracking on Colombia’s longstanding extradition agreement with the U.S. It’s terrible, but it’s what happens when you negotiate with terrorists from a position of weakness.”

“It’s also what happens when you cooperate with tyrants…. Petro has been the foremost Latin American advocate of “engagement” with narco-dictator Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela and puppet dictator Miguel Díaz-Canel in Cuba [because] he wants both regimes to use their leverage over the ELN in Colombia’s favor. [I]t’s a fool’s errand, because internationally ostracized dictators have nothing to gain from increasing stability in the region.…”

“The icing on the cake is that Petro has also joined the ranks of Latin America’s pro-China voices. In February, his Ministry of Foreign Affairs went so far as to issue guidelines instructing Colombian officials to refuse contact with Taiwan….”

On China’s activity in Latin America

October 2024

Op-ed in the Miami Herald on Huawei:

“Its primary goal was and remains, the domination of the global wireless market on Beijing’s behalf, combined with the expansion of the Chinese Communist Party’s ability to spy on and disrupt other countries’ communications.”

“I urge Latin American leaders not to heed Huawei’s siren song. No 5G deal is worth allowing a totalitarian dictatorship to spy on and interfere in a free nation’s affairs.”

March 2022

Remarks at Senate Committee on Foreign Relations subcommittee hearing on China in Latin America:

“Unfortunately, many of these newer leaders in the region have expressed admiration for the Communist Party in China’s model, even as they turn a blind eye and in many cases are supportive of the regimes that are creating tremendous suffering in Cuba and Venezuela and in Nicaragua.”

“So Beijing sees this, and they’re seizing the opportunity to grow both their influence and their power in the Western Hemisphere. As an example, their Belt and Road Initiative uses massive infrastructure loans and projects to lure nations into economic and political dependency — debt traps. That’s now spread to Argentina, Brazil, Barbados, and Panama. And in their annual report last year, the bipartisan US-China Security and Economic Review Commission found that the Communist Party of China is taking advantage of its economic importance and political relationships to encourage governments across the region to make domestic and foreign policy decisions that favor the CCP and undermine democracy and free markets in the region.”

“Their intentions in the region are not to be active because they want to make life better for people living in the Western Hemisphere. They care only about power and influence. They don’t care about stability or economic development. And so even as increasing exports to China boost the economies of some of the nations in these regions, the Communist Party of China is pushing countries to remain dependent on mining and the export of other natural resources instead of partnering with them to develop and industrialize their economies. It’s encouraging them to weaken or even break their own environmental, social and [governmental] regulations by promising them increased investment from China in return.”

“And they do this because they know that chaos in Latin America and the Caribbean would severely hurt us, destabilize us, who they view as their primary and central rival. If cartels have greater operating freedom to send drugs and violence across our border, it worsens the opioid and fentanyl epidemic and [amplifies] gang violence in our communities. If more countries go the way of Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba, you’ll see massive new waves of illegal immigration and human trafficking that’s associated with it.”

“So we simply can’t afford to let the Chinese Communist Party expand its influence and absorb Latin America and the Caribbean into its private political-economic bloc. That would leave our country worse off and ensnare the people of Latin America and the Caribbean into a generation of suffering and repression. So I’m hopeful that our nation will begin to address this threat head on and seriously revitalize our engagement in the region.”

This article was updated on November 13 to reflect the confirmation of Rubio’s nomination.