How stable is the US-China relationship?

Ian Bremer

GZero Daily, April 11, 2024

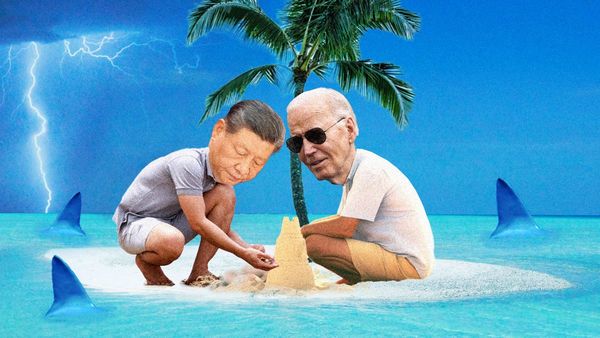

The most geopolitically important relationship in the world is fundamentally adversarial and devoid of trust. Its long-term trajectory remains negative, with no prospect of substantial improvement.

And yet, ever since US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping met at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Woodside, Calif., last November, US-China relations have looked comparatively stable amid a sea of chaos.

In the months that have followed, both sides have continued to seek steadier ties through frequent high-level engagement as well as new dialogue channels on a wide range of policy areas. In January, the US and China resumed military-to-military talks for the first time in nearly two years. On April 2, Biden and Xi spoke by telephone and ratified their ongoing commitment to manage tensions. The presidential call came after the third in-person meeting between US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in less than a year on Jan. 16-17. It set the stage for US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s trip to China this past week – where she met with senior Chinese officials, local and provincial leaders, and top economists – as well as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken's upcoming visit. Both militaries are currently in the final stages of preparation for a maritime dialogue and a likely ministerial meeting at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June.

However, while better managed than they have been historically, US-China relations are coming under stress from a number of flashpoints that threaten to disrupt the relative calm that has prevailed since Woodside.

Second Thomas Shoal. This is the most likely, imminent, and dangerous tripwire for US-China military conflict, following an incident on March 23 in which Chinese Coast Guard ships fired high-pressure water cannons on a Philippine vessel attempting to deliver construction materials to the rusting BRP Sierra Madre – a symbolic Philippine warship, home to a small detachment of Philippine marines, that was intentionally grounded by Manila in the South China Sea’s Second Thomas Shoal in 1999 to assert Philippine sovereignty over the disputed territory.

Beijing refuses to allow any construction materials to reach the Sierra Madre, and Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos feels he must continue sending materials to prevent it from sinking lest he renounce Manila’s claim. The latest run-in injured several Filipino sailors but stopped short of causing fatalities. US defense officials believe that if a Philippine sailor were to get killed, Manila would invoke its Mutual Defense Treaty with Washington, prompting the US to send military escorts for Philippine resupply ships. Chinese contacts say that if that happened, Beijing would consider towing the Sierra Madre off the reef, setting up a showdown between the US and Chinese navies.

Tech competition. Xi views Washington’s ever-expanding restrictions on China’s advanced semiconductor and artificial intelligence industries – and its pressure on US allies like Japan, the Netherlands, Germany, and South Korea to follow suit – as an effort to curb his country’s technological and economic development. More than ordinary trade barriers, tech restrictions get under Xi’s skin because they hit at the heart of his strategy to shift the sources of Chinese growth away from real estate and infrastructure investment toward “new productive forces.” Insofar as the US containment policy persists – and it will, as it is driven by a bipartisan national security consensus to “de-risk” – Beijing will eventually be compelled to retaliate.

Trade. A sticking point for labor unions in an election year, Chinese industrial “overcapacity” was a central theme of both Biden’s call with Xi and Yellen’s China trip. Washington’s core contention is that China accounts for a third of global production but only a sixth of global consumption. As a result, China’s heavily subsidized (or outright state-owned) firms are flooding Western and global markets with low-cost goods, especially in key sectors such as electric vehicles (EVs), batteries, and solar photovoltaics, benefiting consumers worldwide through lower prices – and reducing emissions by increasing the adoption of renewables – but hurting the less competitive American manufacturers.

American accusations ring hollow in Beijing when the US is simultaneously granting TSMC, the world’s leading producer of semiconductors, billions of dollars in subsidies to expand chip manufacturing in America. Separate but related, the irony of the US (and Europe) complaining about China making the global energy transition cheaper while at the same time chastising the country for not doing enough to decarbonize their economy is not lost on the Chinese and many in the global South. But I digress.

From Washington’s perspective, overcapacity is a problem at the core of China’s industrial policy model that will be made worse by Xi's aversion to boosting domestic consumption. Given the election-year politics of the issue for Democrats, at least some market access barriers before November are likely – whether through the Section 301 review of China’s steel industry, the Chinese EV data security probe, and/or the likely realignment of Trump-era tariffs on EVs and other imports. Still, anything Biden might do on trade pales in comparison to the risk of major tariff escalation that Beijing will face if Donald Trump returns to the White House.

Taiwan. China’s leadership has concluded that Taiwanese President-elect William Lai is an irredeemable separatist, and Lai sees little upside in trying to persuade Beijing otherwise. Xi’s embrace of Lai’s Kuomintang predecessor, Ma Ying-jeou, in a high-profile meeting on April 8 didn’t help defuse tensions. Lai’s inaugural address on May 20 will accordingly set the stage for a gradual erosion of cross-strait ties over the next four years. The pressure will start as soon as this summer when China begins to regularly enter Taiwan’s contiguous zone, “erasing” the island’s territorial waters and airspace. While these moves will be calibrated and telegraphed to Washington through backchannels to limit retaliation, Lai could escalate and force Biden to respond with a show of resolve in support for Taipei that risks a dangerous cycle of escalation.

But while these irritants will strain the bilateral relationship, there are still plenty of reasons for both leaders to want to maintain relatively stable ties, at least through the US elections.

Biden can’t afford to start a new war when he’s already managing two abroad – one in Ukraine, one in the Middle East – and fighting another at home. Xi continues to face major domestic economic challenges that require him to be much more geopolitically cautious than he would otherwise. Tensions are further constrained from spiraling out of control by enduring interdependence between the world’s two largest economies, neither of which would benefit from faster decoupling let alone military conflict.

Of course, as we saw both in 2022 with former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan and in 2023 with the Chinese surveillance balloon incident, accidents and miscalculations can easily overwhelm leaders’ ability to manage the tensions. But the communications channels established since November make such flare-ups less likely.

Neither the US nor China want a free-fall in their relationship this year, and thanks to Woodside, they now have the tools to avoid one. The Woodside truce may bend, but it won’t break.