Se não existe precisaria inventar, ou aparecer alguém.

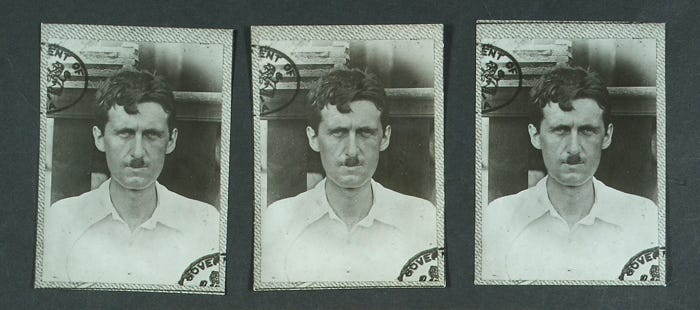

Os tempos são sem dúvida orwellianos, o que é revelado pela linguagem.

Em certos ministérios, e não apenas no MEC, os funcionários da Verdade (do momento), estão empenhados em apagar o passado para melhor controlar o presente e determinar o futuro.

Em outros ministérios, como o da Damaris, os tempos são surrealistas-dadaistas-antropofágicos, se não é coisa pior: estupidez, pura e simples...

Os tempos não apenas orwellianos em certos ministérios, mas stalinistas, aqueles do Fotoshop manual: primeiro se apagava a foto do sujeito, depois mandava apagar o sujeito.

Em todo caso, vale melhorar a linguagem.

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

George Orwell’s Six Rules For Great Writing

How to write clearly and effectively

“But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.”

George Orwell

Winston Smith is a fictional character and the protagonist of George Orwell’s 1949 novel ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’. He works at the Records section in the Ministry of Truth where he updates Big Brother’s orders and Party records so that they match new developments. He helps correct the flow of history to ensure that Big Brother is never seen to be mistaken. Big Brother can on no occasion be wrong and Winston is just one of thousands who work to correct the past in order to keep the people ignorant of their history.

“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

― George Orwell

In Chapter five, Winston has lunch with a man named Syme, an intelligent Party member who works on a revised dictionary of Newspeak, a controlled language, of restricted grammar and vocabulary, meant to limit freedom of thought. Syme says to Winston that the purpose of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought possible in order to make thoughtcrime, a crime against the state, impossible.

There should exist no words that are capable of communicating independent, rebellious thoughts. Because if you are able to numb the language, you in turn numb the mind. Thought corrupts language, so language must also be able to corrupt thought.

“If people cannot write well, they cannot think well, and if they cannot think well, others will do their thinking for them.”

It is impossible to conceive of rebellion if there are no meaningful words to illustrate such a cause. And so, Big Brother sought to continually diminish the available vocabulary until comprehensive thoughts are reduced to meek terms of simplistic meaning.

…

‘Politics and the English Language’ was published just a couple of months before the publication of ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’. This essay provides great insight into Orwell’s fears surrounding the declining state of language in the English speaking world, fears he expressed so boldly in ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’.

I first came across George Orwell’s essay ‘Politics and the English Language’ many years ago and I have tried to use it as a guide for my writing, referring back to it every so often when I fear I am losing my way.

The essay opens with, “Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it.” Orwell, in his usual calm and measured way, shares his thoughts on how the modern writer could help to improve the general state of language. He lists six rules for writing that he believes will aid the fight against restrictive language:

“(i) Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

(ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

(iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

(iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

(v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

(vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”

Notice the words ‘never’ and ‘always’, suggesting these rules are absolute and must never be broken. But, Orwell himself did not obey them. ‘Politics and the English Language’ is riddled with the passive voice and many unnecessary words. The listed rules are an impossible standard, but Orwell knew this himself.

The point of the essay was not to introduce a list of strict commandments, but to encourage the writer to think about how and why they are using words. The writer should be constantly questioning whether the words they write are clear and worthwhile. For the purpose of language is for expression, rather than concealment from one’s truth.

“A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus:

1. What am I trying to say?

2. What words will express it?

3. What image or idiom will make it clearer?

4. Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?

And he will probably ask himself two more:

1. Could I put it more shortly?

2. Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?”

Every word Orwell wrote, particularly in the late 1930s and 40s, was used as a weapon against the wicked force of his age, namely totalitarianism. This was his life’s purpose — to defend language from those who wish to ‘make lies sound truthful and murder respectable’.

Language in Britain, Orwell wrote, was sloppy because the people’s thoughts were sloppy. The First World War left Britain in a state of shell shock, amnesia, and hopelessness. The British thought their nation to be decadent and rotten, an empty shadow of its former self. What was once a proud and upright culture was now hunched over a bayonet. It was supposed that the English language must follow also.

But, Orwell did not believe this to be so. Language, Orwell wrote, is not a natural growth that is bound by the conditions of the time. Instead, it is an instrument that we are able to use for our own purposes.

“A man may drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more so because he drinks.”

The bad habits caused by our foolish thoughts can be removed, producing purer thoughts and, in turn, purer language. Orwell argued that the decline of the English language is reversible only if we are aware of our corrupt ways. Orwell’s six rules demand the writer to be aware of their crooked sentences because they highlight the habits that prevent clear thought.

He continues his argument by laying out a couple of examples. Here is a comparison between good English and bad English:

“I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.”

This passage uses compressed, short, Anglo-Saxon words that everyone can understand. It is a slightly dated example, but the meaning and the intention remains clear. The images the passage portrays are vivid, they allow the mind clear pictures of the author’s thoughts and purpose.

“Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.”

Orwell himself admits this example to be an exaggeration. Yet, there is truth in hyperbole and it is often necessary when trying to express an idea so that others may understand. Each word here is hazy and thoughtless; there is a lack of exactness, no word is concrete, everything is abstract. The sentence avoids emotion and appears to be a confusion of scientific, technical, ready-made words that have been thrown together to create the allure of knowledge.

The quality between the two is clear. The first example lets the meaning of the picture choose the word, whereas the second example picks words from their sight and how easily they can be put together.

“In prose, the worst thing you can do with words is to surrender them.”

…

Language can cause people to cry, cheer, blush, it can sing songs, tell stories, speak the truth and teach lessons. Language can hum rhyming poetry, drift with rhythm and dance with lights and sounds. It is a beautiful gift — a gift many of us are unaware of.

Language is powerful for it allows man to express their own story and truth to the world, but with such a gift comes a duty that we must be mindful of. This recognition is crucial if we are to avoid the horror of ‘Nineteen-Eighty Four’.

Orwell was encouraging writers to be clear, communicative, simple, strong and purposeful. Obscure, complicated, scientific, hollow and senseless writing betrays the greatest power that God has given to us.

“The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.”

― George Orwell, Politics and the English Language

Thank you for reading.

Harry J. Stead