Ou como diríamos no Brasil: se ficar o bicho, se correr o bicho pega...

A dictator’s embarrassment is generally a cause for celebration. But what if it also threatens a national tragedy and a bona fide global problem?

Xi Jinping’s assertion of total personal control over the Chinese regime in October was an ominous turn in Chinese history and a cause for mourning amongst friends of liberty everywhere. Since 2020 a major anchor of Xi’s personal authority has been the “all out people’s war to stop the spread of the corona virus,” that has put “the people and their lives above all else” i.e. Zero Covid.

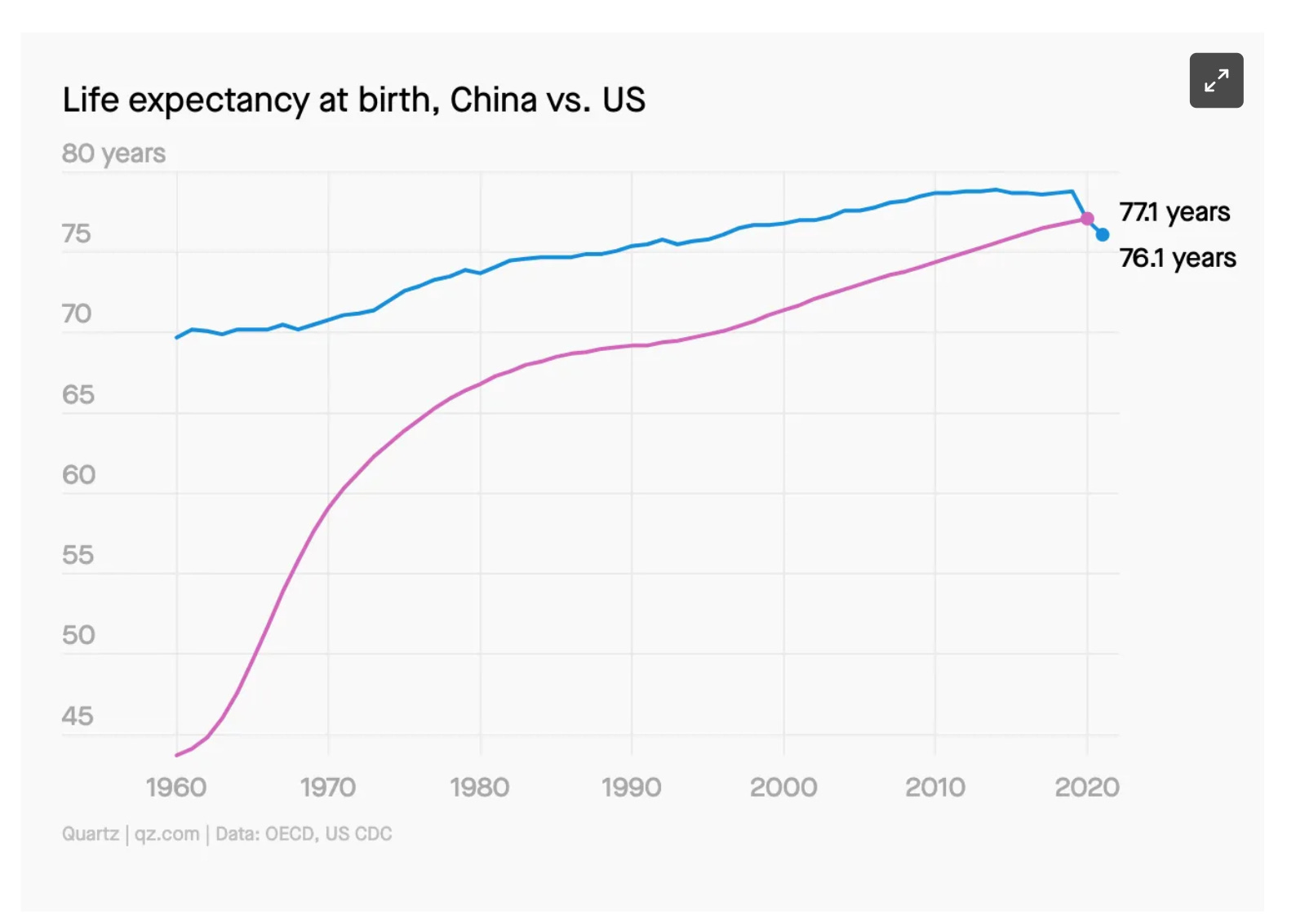

Amongst Xi’s regime’s proudest boasts is the fact that China has registered only slightly more than 5000 COVID deaths compared to more than 1 million suffered by the US. From 15 May 2020 to 15 February 2022, whilst many thousands around the world were dying from COVID every day, there were only two COVID-19 deaths in mainland China. Even allowing for propagandistic understatement of the Chinese numbers, Xi’s China has clearly been far more successful in protecting its population from the worst effects of virus than any country in the West. As a result, it cannot be stated too often, China’s life expectancy overtook that in the United States in 2021, a truly historic marker.

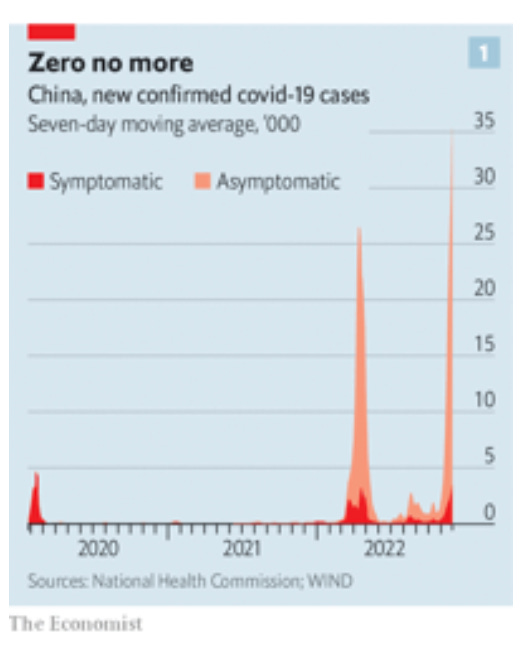

But now, only weeks after Xi’s triumphant party Congress, the zero covid policy is in crisis. The disease is spreading and China’s population is no longer willing to put up with it.

Desperate locked-in workers and indignant students have taken to the streets. Bottle-throwing residents have waged pitched battles with riot police. Chinese diaspora communities have braved the ominous presence of embassy security officials to stage protest meetings.

This is clearly a test of Xi’s authority, the most profound since he has taken power. One must profoundly admire the courage of the protestors and sympathize with the outrage and desperation triggered by successive waves of capricious lockdowns. In large parts of China, ordinary life has become hard to sustain. At the same time it is hard to resist Schadenfreude at the expense of Xi. Xi Jinping’s ‘myth of infallibility’ is being tested.

But as attractive as it may seem to side with the protests against Zero Covid this begs the question. What is the policy alternative? The fact that abandoning zero COVID would be a blow to Xi does not make that the right policy. The dilemma facing Beijing goes beyond the question of Xi’s legitimacy. As ludicrous as zero COVID has come to seem, as oppressive and capricious as its intrusions are in the everyday lives of Chinese people, it has saved huge numbers of lives. And if Beijing were to follow the demand to abandon the policy, this would likely result in a public health disaster not just for the CCP but for China.

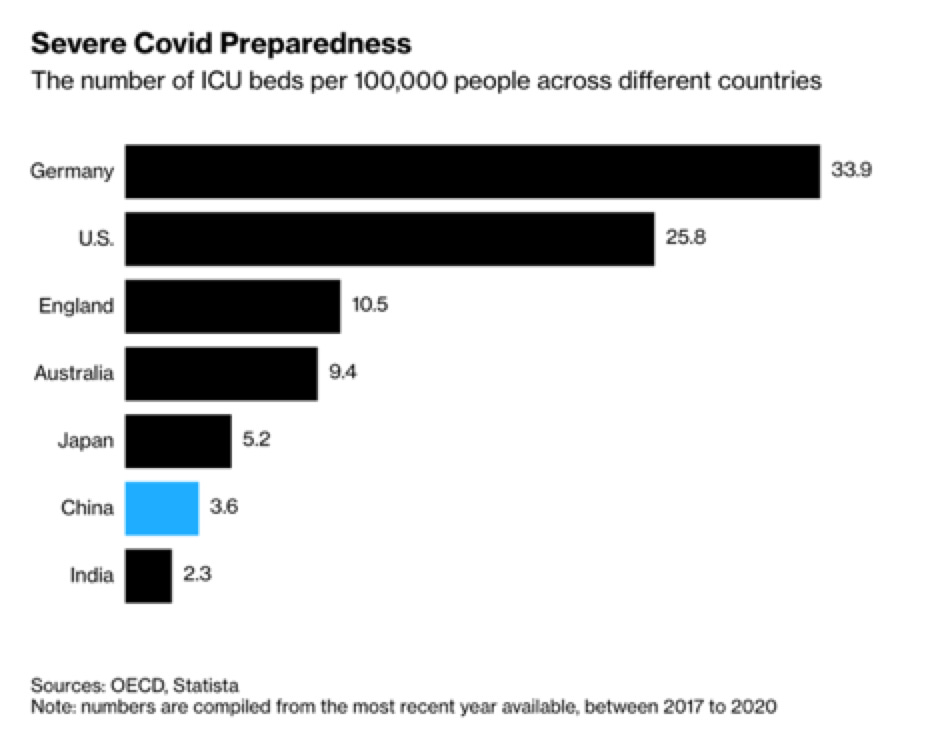

Omicron is less dangerous than Delta but its infectiousness is extremely high. If the pandemic is allowed to run unchecked, hundreds of millions of people will become infected. Even with a low rate of severe cases, China’s medical system will be placed under impossible strain, not just in a handful of cities as in 2020, but across the country. Hundreds of thousands of vulnerable people, if not more, will likely die.

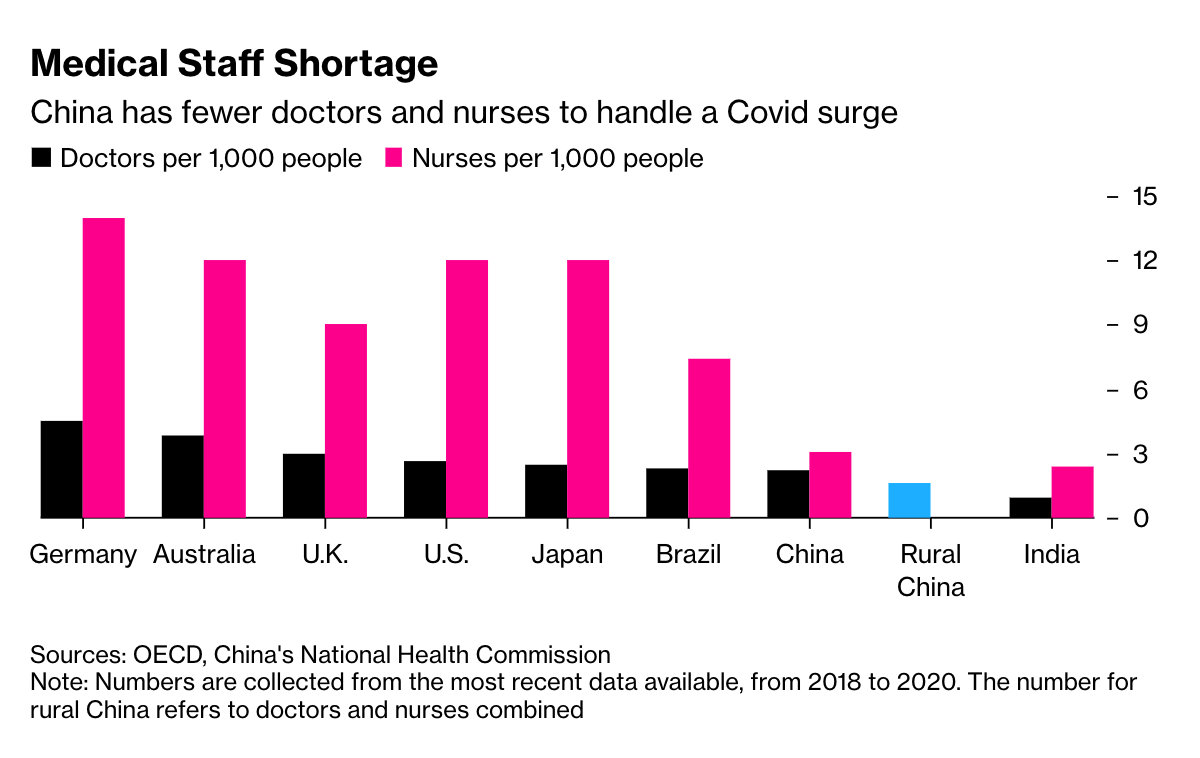

It bears repeating that though China may be a remarkable economic success story, it is still a middle-income country and its welfare net and health care provision are fragile, especially in the countryside, where hundreds of millions of people still live.

All told, by the end of 2021, 970,036 community hospitals had been established in mainland China, employing more than 3 million healthcare workers (around 1 community hospital for every 1,400 residents)6. These millions of local healthcare workers could provide a frontline force with which to contain a nationwide COVID-19 outbreak, but they would require training and investment, which Beijing has so far failed to deliver.

In May 2022 during the emergency in Shanghai, a paper in Nature Medicineestimated that lifting China’s COVID restrictions could results in a “tsunami” of infections. Based on the vaccination rate as of the spring of 2022 the Nature authors predicted that China would need more than 15 times the number of intensive care beds that are actually available. Their modeling suggested a likely toll of 1.55 million deaths. That is a grim figure. An estimate by The Economist, predicted something closer to 680,000, assuming that all intensive care needs can be met, which is far too optimistic.

It is worth noting that even the worst case scenarios do not foresee a catastrophe for China on the scale of America’s or Europe’s botched handling of the crisis. Scaled to population, America’s 1 million deaths would be equivalent to over 4 million in China. That does not seem on the cards. But the figure of between 500,000 and 1.5 million deaths are predicted by most studies would nevertheless be a shattering disaster. Scenes of chaos in hospitals like in Wuhan in January and February 2020 or Hong Kong in early 2022, played out hundreds of times across China are a nightmare that no one can wish for.

In 2020 Beijing avoided this horrifying scenario with a short, sharp national lockdown that contained the epidemic to a cluster of cities in one province. Omicron is so infectious that at this point the outbreak may already be too widespread to be contained without truly draconian nationwide measures - something akin to a nationwide application of Shanghai’s measures in the spring of 2022. But that is itself a horrifying prospect and, as Shanghai now demonstrates, it is not one that offers any long-term solution. Nothing guarantees that Shanghai will not have to go into lockdown again some time in the coming months.

Some optimists say that Omicron is simply not that dangerous. But, if Hong Kong is anything to go by, elderly Chinese should go in fear, especially those who are unvaccinated, of whom there are far too many.

To make a continuation of zero COVID bearable, the regime would need to implement a much kinder and more reasonable quarantine model than that applied in Shanghai. But how to implement that across the largest population in the world in tens of thousands of cities, small towns and villages? It is a mind-boggling challenge. On November 11 the regime issued a new playbookwith 20 key parameters to guide local officials in managing the trade offs. Whether that will be enough is anyone’s guess. The hard lesson from Shanghai was that targeted lockdown measures did not work to contain Omicron, whereas the blanket lockdown did. If, as seems likely, Beijing, the CCP and local authorities fail to find a compromise, they, like their Western counterparts in 2020 and 2021, will fail in every direction. They will fail to contain the epidemic. They will damage the economy seriously and provoke further outrage.

If on the other hand Beijing abandons Zero Covid completely, given the infectiousness of Omicron it could be facing an epidemic running at the rate of tens of millions of new infections per day. The disruption of repeated Zero-Covid-lockdowns is huge, but as Europe and the US struggled to digest in 2020, a rampant pandemic has significant economic costs too.

***

There are no simple answers. Xi’s regime is weighing huge risks. Anyone who imagines that that can be a matter of indifference to the rest of the world or is tempted to indulge in Schadenfreude has not learned the first lesson taught in February 2020 - what happens in Wuhan does not stay in Wuhan.

Apart from the human catastrophe facing China, a new wave of the pandemic raises a serious risk of further mutation. Some medical experts argue that precisely because the Chinese population is largely immunonaive it is less likely to mutate new and dangerous strains of the disease.

Let us hope they are right. But the very fact that we are weighing these options points to the basic fact that at this moment Xi’s China has become time machine taking us backwards in time, not decades, to the era of Mao, or centuries, to the age of the imperial dynasties - the vistas that came to mind at the time of the Party Congress - but to the dark days of 2020 - first to the drama of Wuhan and then on from there to the horror of Bergamo and New York’s chaotic emergency rooms. Our problems then are China’s problems now, how to weigh up mass casualties against huge economic loss.

Unlike the first strain of COVID, the Omicron variant that is now overwhelming China’s zero COVID policy, did not originate in China. Omicron was a product of the sweeping global pandemic, which Zero COVID for two years protected China against. Now with the disease threatening to accelerate again, it is us who once again should guard against the assumption that China is “not our problem”.

There is a way out of Beijing horrendous impasse: mass vaccination and an ample supply of anti virals to help patients fight the disease. But that begs the question.

China was the first country to vaccinate. It has vaccines which when used in a triple dose are highly effective against hospitalization and death. The lack of mRNA vaccines is not the issue. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of China’s huge population have completed the basic two-course regime. Where Beijing has failed is in rapidly delivering the third and fourth round of boosters and in ensuring that the most vulnerable population, those over 60, are properly covered. As of the latest figures cited by Bloomberg, “only 69% of those aged 60 and above and just 40% of over 80-year-olds have had booster shots.” That leaves tens of millions of elderly with no protection at all. They are the people who died in Hong Kong.

As far as I am aware there is no fully convincing explanation for this failure to provide comprehensive coverage particularly of the elderly.

There are a lot of good studies in the specialist literature in medical sociology and psychology that help to explain some of the vaccine resistance.

China became a victim of its own haste in rolling out vaccines on a rough and ready basis to those under the age of 60. This created the perception that the vaccines were not properly tested or safe for use amongst more fragile elderly people.

China has an unfortunate track record of vaccine scandals and the lack of good data on the safety and efficacy of China’s shots among the elderly in homegrown vaccine's clinical trials does not build confidence.

Health workers have been cautious about recommending vaccines for those with high blood pressure or autoimmune disorders and given the negligible chance of COVID infection, there seemed little reason to take the risk. In most of China, COVID has never been more than a news report. Thanks to the success of the 2020 measures, many cities have never logged a single case and elderly people regard the threat as very remote.

The Chinese population and the regime also suffered from “other people’s problem”-syndrome. Not unreasonably they convinced themselves that COVID was an issue for the failed and degenerate West. Rather than joining a broad global front to endorse precautionary vaccination and boosting with whatever vaccinations were too hand, Beijing allowed the media to spread questions about the efficacy and safety of vaccines in general.

But the real question, given the CCP-regime’s supposed grip on society, is why personal attitudes and public opinion matter at all. Why did the regime not impose vaccine mandates?

One part of the explanation may be that the primary aim of zero Covid was to minimize the number of cases. It thus made sense to prioritize vaccinating the more mobile, younger population, rather than elderly people who can be sheltered by simply staying at home.

Remarkably, at the city level where the vaccination program have to be delivered, the authorities have repeatedly shrunk from forcing the issue. During the height of its bout with COVID, Shanghai city authorities gave cash rewards and did vaccination house calls for the elderly. That raised the delivery of a first course of vaccine to nearly 70% of the elderly group. But without a booster that offers only little protection.

When Beijing attempted to impose the first vaccine mandate in China, the result was an embarrassment. Even with essential retail outlets exempted from the vaccine requirement, within 48 hours the public outcry against coercion forced a retreat. In September, China’s National Health Commission clarified that whilst cash incentives and insurance for “vaccine accidents” are considered acceptable, vaccinate mandates were rejected as national policy. A Health Commission expert declared that

These practices (mandates) violate the principle of vaccination and also cause inconvenience to the masses. Wu Liangyou said that the new crown virus vaccination should be carried out in accordance with the principles of knowledge, consent, voluntariness and seeking truth from facts, and emphasized that the introduction of vaccination policies and measures must be rigorous and prudent, carefully evaluated, to ensure compliance with laws and regulations, and strictly aside by the bottom line of safety. It is reported that the National Health and Health Commission will guide all localities to make good use of health codes and vaccination codes, and resolutely put an end to the two-code joint inspection and compulsory vaccination.

The squeamishness of the regime when it comes to shots is remarkable. Clearly, the CCP-regime does not resist coercive measures. One can hardly imagine anything more coercive in peace time than the closed loop production system in which workers are confined to their factories. Nor does it shrink from costs. The gigantic testing apparatus of Zero Covid that allows a hundred million people to be tested in a single days is very costly. According to the Economist:

The 35 largest firms producing covid-19 tests raked in some 150bn yuan ($21bn) in revenues in the first half of 2022 alone. A broker, Soochow Securities, has estimated China’s bill for covid testing at 1.7trn yuan this year, or around 1.5% of gdp. That number, which some consider an underestimate, equates to nearly half of all China’s public spending on education in 2020.

This highlights the need to understand the complexity of CCP rule, the way in which the appropriate limits of its coercive power are defined and the way in which it prefers certain tactics and instruments to others.

Even after the Hong Kong debacle was clearly visible in early 2022, rather than prioritizing vaccination Beijing preferred to counted on grit and generalized discipline. As the Economist puts it:

In the spring of 2020 the collective self-sacrifice of hundreds of millions of Chinese surprised the world, when their willingness to stay indoors for weeks halted the outbreak that began in Wuhan. Mr Xi over-learned the lessons of that success, declaring self-discipline, vigilance and isolation the key to defeating the pandemic.

Those worked against the original variants of COVID, but against a strain as infectious as Omicron, zero COVID is fighting a losing battle. Even now, in early December, Beijing is still shrinking from vaccine mandates and promising, instead, that “big data” will allow it to target the most vulnerable for special protective measures. Ironically, that confirms the common place of Beijing’s omniscience whilst actually demonstrating the limits of its grip.

Even in the best-case scenario, assuming Beijing’s new vaccination targets are met, it will not be before early 2023 that the vulnerable elderly population have the protection they urgently need and will allow Beijing to escape its impasse.

In any case, the dilemmas facing Beijing go far beyond the authority and legitimacy of Xi Jinping. As The Economist put it in a truly excellent summary of the situation:

… Mr Xi faces the choice between enforcing zero-covid even more strictly, even though that would invite a recession and public fury, or allowing the disease to spread very widely, with calamitous loss of life. Attempting to chart a middle path is only helpful if he uses the time he gains to raise vaccination rates, stock up on antivirals and expand icus. And not only are all Mr Xi’s options unpalatable; he is running out of time to choose one.