Whither China?

With the inflation (or should we say price shock) drama in the West largely played out, there is no story more important in the world economy right now than the question of China’s future.

The mood on China has shifted spectacularly in the last 18 months. Whereas once the prevailing impression was one of awe, now what prevails is a negative story. This is assembled out of data, official news from Beijing, quotations from off the record interviews with interlocutors in China and more or less commonplace assumptions about economic and political development. This may be bricolage. But it is the best we can do. There is not other way of forming a view. But in such moments it is a good idea to check our prejudices.

On the podcast, Cam and I took on the challenge of making sense of China’s current situation.

| China's Economic Crisis Ones and Tooze 39:43 |

In this mini-series of newsletters I want to review the main lines of interpretation in Western public debate about China. Six lines of interpretation immediately come to mind which will form the first installments in the series.

(1) Part I - Regime impasse

(2) Part II - Balance sheet recession

(3) Part III - Keynesian structuralist

(4) Part IV - Dual-circulation, Siege economy

(5) Part V - Zero COVID in hindsight

(6) Part VI - One China or many Chinas? Regional economies and debt crises

To make sure you get all the parts of the mini-series, sign up here and consider supporting the Chartbook Newsletter project.

***

The news out of China is not good. Growth has slowed dramatically in recent years. Under the impact of zero-COVID it was sometimes brought to a halt. The recovery since the abrupt end of zero-COVID has seemingly run out of steam. The housing market is in crisis. China has been spared the inflation that afflicted the rest of the world. Instead seems to teeter on the edge of deflation.

Reading the business-cycle is a difficult business at the best of time. Though one measure of inflation - CPI - moved into deflation this month, China’s core inflation actually appears to have bottomed out and ticked up slightly.

In recent months the export numbers have turned downwards. But this is against the backdrop of world historic export records in 2022. It was always a mistake to read those exports and the resulting giant trade surplus as signs of economic health. They were rather the opposite a symptom of sluggish domestic demand.

For all the negative talk we should bear in mind that most economists both inside and outside China expect its economy to grow at 5 percent per annum. Whatever the fundamentals, it is a long way from Japan-style stagnation.

Source: FT

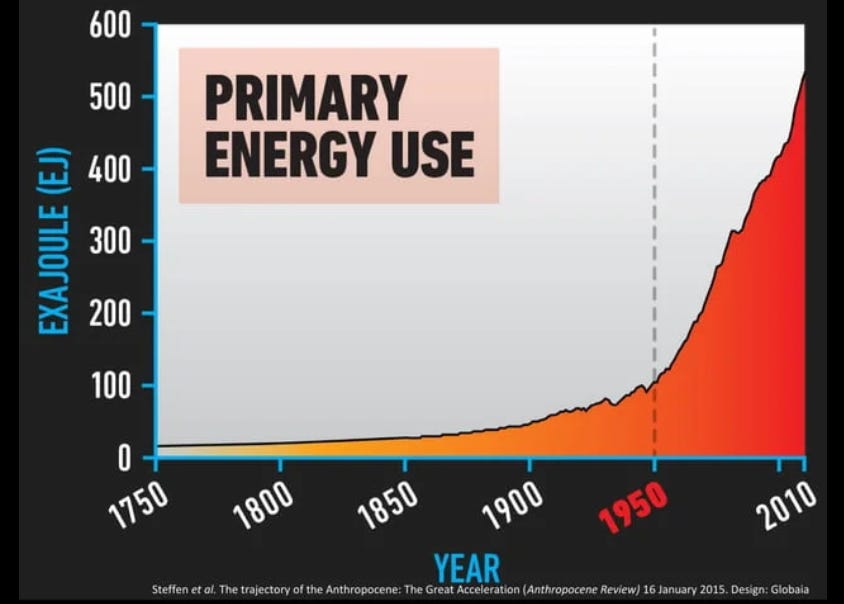

But, beyond the mood swings of the media cycle, what is going on is clearly very dramatic. We are witnessing a gearshift in what has been the most dramatic trajectory in economic history. The question is how to interpret it.

***

The most obvious line for many Western interpreters to take is that China’s problems are basically political. Specifically they are to do with the unpredictable and ideologically motivated turns taken by Xi’s government, which themselves reflect the irredeemably authoritarian quality of the Chinese regime. Xi’s regime may undertake efforts to revive the economy with stimulus measures, but they lack conviction.

This interpretation is common place in the West but it has been presented in quintessential form in recent weeks in essays in the twin flagship publications of American liberalism, one by Li Yuan in the New York Times and the other by Adam Posen in Foreign Affairs. The two pieces differ in style, in their sources and in the point they are trying to make. But they deliver a common message. The problems of China’s economy are political and though they center on Xi they go beyond him and concern the entire system.

On the basis of her no-doubt excellent contacts in the Chinese business class Li Yuan paints a picture of a resentful stand off between “business owners” and the regime, an impasse which is resistant to any recent efforts by the party to raise spirits.

Stocks on the mainland and in Hong Kong, where many of China’s biggest private enterprises are listed, fell on Thursday but regained their footing on Friday. Some entrepreneurs rushed to praise the guidelines in official media. But in private, others I interviewed dismissed the party’s pep talk in words that can be best translated as, “Save it for the suckers.” By now it’s obvious that the country’s economic problems are rooted in politics. Restoring confidence would require systemic changes that offer real protection of the entrepreneur class and private ownership. If the party adheres to the political agenda of the country’s paramount leader, Xi Jinping, who has dismantled many of the policies that unleashed China’s economy, its promises on paper will remain just words.

Speaking to her off the record “business-owners” vented their frustrations with the regime.

The stock markets’ reaction was very honest, one tech entrepreneur said. Investors sensed how desperate the party is, he said, and how meaningless the guidelines are. At its core, he said, the issue of confidence is a matter of government credibility. Beijing has lost nearly all its credibility in the past few years, he said. If it really wants to remedy the situation, it can at least apologize for its wrongdoings. He cited a document that the party issued after the Cultural Revolution admitting some of its mistakes under Mao Zedong’s leadership from 1949 to 1976. Other people pointed to similar steps the party took then, such as rehabilitating persecuted cadres and intellectuals. At the very least, they said, the government should release Ren Zhiqiang and Sun Dawu, outspoken entrepreneurs who are serving 18-year prison sentences after their arrests in the recent crackdown. Or, another entrepreneur told me, the government could return the fines it imposed on his company, which he believed served as punishment for not toeing the party line and as revenue for an overextended local government. He said he felt that he had been robbed. None of the business owners I talked to expects the government to take any of these steps. They all spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of punishment by the authorities.

It is hard to know how seriously to take such spleen from aggrieved business people. Are they representative of opinion at large or is there selection bias at work, in that those who are most upset are also most likely to talk to a Western journalist. And how far are the grumpy views of frustrated managers, anywhere indicative of what actually gets done in business? In any case, Li Yuan uses these quotes to suggest that any bond of trust between the regime and vocal segments of business opinion has snapped. Though the regime in the summer of 2023 is trying to curry favor with business, everyone remembers the rollercoaster of recent years.

In 2021, a commentary headlined, “Everyone can feel it, a profound transformation is underway!” was reposted on many of the most important official media websites. Praising the suppression of the private sector and the policy proposal known as “common prosperity,” the commentary said, “This is a return from capital groups to the masses, and a transformation from a capital-centered approach to a people-centered approach.”

In the spring of 2023 the regime reversed course and turned back to private business:

“We have always regarded private enterprises and entrepreneurs as part of our own,” Mr. Xi said in March, repeating himself from 2018. The head of the National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s economic planning agency, held a series of meetings with business leaders, pledging support. Then came the 31-point guidelines. Most Chinese businesspeople support the government and willingly follow what it says. Still, the comments from some entrepreneurs on state media read more like pledges of loyalty to the party than authentic expressions of confidence. Ben Qiu, a lawyer who practices law in Hong Kong and the United States, summed up the executives’ comments in a social media comment: “The emperor’s clothes look fabulous.” … No matter how many supportive words the party offers now, it will be hard for the private sector to feel confident.

Effectively, Li Yuan suggest that China is experiencing something akin to a “capital strike” spreading through the business community. And this matters, because of the overall weight of the private sector in China’s modern economy.

The private sector … contribute(s) more than 50 percent of the country’s tax revenues, 60 percent of economic output and 80 percent of urban employment, according to none other than Mr. Xi in 2018.

If Li Yuan had wanted data to back up her argument she could have turned to the output of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington DC, whose team tracks the balance of public and private sectors in the Chinese economy.

The data show a lurch towards the priority of state investment during the initial shock of COVID and no substantial recovery by the private sector since. So far at least the pessimism of Li Yuan’s informants is born out.

The head of the Peterson Institute is Adam Posen who has emerged in recent months as perhaps the leading public critic of the Biden administration’s industrial policy. His latest piece on China in Foreign Affairs has to be read in this context. Posen is worried that America’s aggressive trade and industrial policies are based on a fundamental misdiagnosis of China’s situation and the Biden team are thus missing a historic opportunity to wrong-foot and undermine the authoritarian regime of the CCP.

For Posen, Xi’s China has reached a tipping point, which unlike Li Yuan he traces less to China’s national history, than the general logic of authoritarian regimes. According to Posen, all authoritarian regimes suffer from a severe case of what is called “original sin”. The lack of credible legal constraints on action by the sovereign makes it hard to sustain a high-functioning economic regime. Since the reform period of the 1980s, the CCP has, in fact, been unusual in holding out for a relatively long time against the temptations of arbitrary rule. But in Xi’s third term the regime is finally succumbing to this universal temptation and - this is the crucial point - broader Chinese society is now waking up to this reality.

Riffing on the famous Martin Niemöller poem - “first they came for the socialists” - Posen describes the unraveling of the bargain between the majority of Chinese and the regime. Most Chinese, Posen claims, live with an understanding that is summarized by the motto “no politics, no problems”. If you pursue your private interest at a distance from politics you could count on remaining unmolested. When Xi wielded his power versus corrupt officials at the top of a party to which 7 percent of the population belong, the rest of China was not displeased. When Xi came down on the tech oligarchs after 2020, the rest of society shrugged. But the extreme policy of zero-COVID in 2022 extended this domineering, capricious logic to the entire society.

Certainly the fiasco of COVID policy in 2022 delivered a severe shock to the authority of the CCP regime. But it is remarkable that Posen attributes so much significance to this one moment, as opposed to longer term factors stressed by critical analysts like Michael Pettis. After all, but for the total mishandling of the pandemic by the West, which massively amplified the second and third waves, China’s regime might well have emerged triumphant from the crisis. Beijing’s policy was not capricious as such, but lackadaisical when it came to vaccination and ineffective against highly-infections variants.

In any case not only stresses the historical importance of the COVID shock, he claims that we can see an immediate impact of the new insecurity in the macroeconomic numbers. “In China’s case, the virus is not the main cause of the country’s economic long COVID: the chief culprit is the general public’s immune response to extreme intervention, which has produced a less dynamic economy.” The immediate reflection of this new anxiety appears for Posen in the dramatic surge in household bank deposits.

On top of Li Yuan’s investment strike, Posen thus sees a comprehensive defensive retreat by Chinese society that is driven not by economic circumstances but ultimately by fear of the regime.

Since Deng Xiaoping began the “reform and opening” of China’s economy in the late 1970s, the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party deliberately resisted the impulse to interfere in the private sector for far longer than most authoritarian regimes have. But under Xi, and especially since the pandemic began, the CCP has reverted toward the authoritarian mean. …. What remains today is widespread fear not seen since the days of Mao—fear of losing one’s property or livelihood, whether temporarily or forever, without warning and without appeal. … The COVID response … made clear that the CCP was the ultimate decision-maker about people’s ability to earn a living or access their assets—and that it would make decisions in a seemingly arbitrary way as the party leadership’s priorities shifted.

SAME OLD STORY

After defying temptation for decades, China’s political economy under Xi has finally succumbed to a familiar pattern among autocratic regimes. They tend to start out on a “no politics, no problem” compact that promises business as usual for those who keep their heads down. But by their second or, more commonly, third term in office, rulers increasingly disregard commercial concerns and pursue interventionist policies whenever it suits their short-term goals. … Over varying periods, Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and Vladimir Putin in Russia have all turned down this well-worn road.

Li Yuan avoids this kind of comparative historical rumination. But she makes a similar point by citing as a witness sociologist Sun Liping, who in recent essays has highlighted the sense of uncertainty afflicting Chinese society. Sun Liping is a well-known public intellectual who recently retired from Tsinghuawhere he taught sociology.

“Why are many people saving money and cutting back on spending? Why are ambitious entrepreneurs reluctant to make long-term planning and investment?” Sun Liping, a sociology professor at Tsinghua University wrote in an article last month. “It’s because they feel uneasy.” He said that for China to get out of its slump, the government needs to create a business environment that can provide reassurance. … “Private enterprises don’t need support. They need a normal social environment” regulated by the rule of law.

Whereas Sun Liping calls for a reaffirmation of law, Posen points out the regime seems to be headed in the opposite direction, responding to emergency by demanding more discretion.

In March, China’s parliament, the National People’s Congress, amended its legislative procedures to make it easier, not harder, to pass emergency legislation. Such legislation now requires the approval of only the Congress’s Standing Committee, which is made up of a minority of senior party loyalists.

Posen thus sees a spiraling breakdown of trust. The lack of trust undermines the credibility of policy. Businesses and householders no longer believe that stimulus means stimulus and that it will not be countermanded by some dramatic intervention of a punitive kind. This lack of credibility makes markets less responsive to policy. Less responsiveness to policy increases volatility as policy becomes less effective. Greater volatility increases the need to intervene. As Posen puts it:

Once an autocratic regime has lost the confidence of the average household and business, it is difficult to win back. A return to good economic performance alone is not enough, as it does not obviate the risk of future interruptions or expropriations. The autocrat’s Achilles’ heel is an inherent lack of credible self-restraint. To seriously commit to such restraint would be to admit to the potential for abuses of power. Such commitment problems are precisely why more democratic countries enact constitutions and why their legislatures exert oversight on budgets.

With Xi having undone the fragile equilibrium that allowed China for decades to avoid the usual fate of authoritarian regimes, China is now embarked on a road back to stagnation and serfdom. It is a vision worthy of Hayek.

You might think that this is all a little overdone and that to compare contemporary China with Venezuela is far-fetched. Indeed one imagines that Posen himself does not mean the point to be taken literally. What he is trying to do with this jarring comparison is to correct the blindspots of Western observers. He wants them to radically revise their outlook for China in a negative direction.

Many outside observers have overlooked the significance of this change (the breakdown of trust and “Long-covid”). But its practical effects on economic policy will not go unnoticed among households and businesses, who will be left still more exposed to the party’s edicts. The upshot is that economic long COVID is more than a momentary drag on growth. It will likely plague the Chinese economy for years. More optimistic forecasts have not yet factored in this lasting change. To the extent that Western forecasters and international organizations have cast doubt on China’s growth prospects for this year or the next, they have fixated on easily observable problems such as chief executives’ fears about the private high-tech sector and financial fragility in the real estate market. These sector-specific stories are important, but they matter far less to medium-term growth than the economic long COVID afflicting consumers and small businesses

The analysts of China that Posen most wants to reach are decision-makers in Washington. Posen is alarmed by the move to protectionism and confrontation towards China. He thinks this is dangerous, because increasing the risk of war, self-harming, because inefficient, and counter-productive, because it strengthens Xi’s regime.

Western officials should adjust their expectations downward, but they should not celebrate too much. Neither should they expect economic long COVID to weaken Xi’s hold on power in the near future. … The perverse reality is that local party bosses and officials can often extract yet more loyalty from a suffering populace, at least for a while. In an unstable economic environment, the rewards of being on their good side … go up, and safe alternatives to seeking state patronage or employment are fewer.

Faced with this situation, what Posen takes encouragement from is that some Chinese rather than turning to the regime for reassurance are opting for self-insurance i.e. are trying to opt out of the future as defined for them by Xi and the regime in Beijing.

If CCP policies continue to diminish people’s long-term economic opportunities and stability, discontent with the party will grow. Among those of means, some are already self-insuring. In the face of insecurity, they are moving savings abroad, offshoring business production and investment, and even emigrating to less uncertain markets. Over time, such exits will look more and more appealing to wider slices of Chinese society.

This is the opportunity that America’s present policy of confrontation is missing.

Washington should think in terms of suction, not sanctions. … The United States should welcome those (Chinese) savings, along with Chinese businesses, investors, students, and workers who leave in search of greener pastures. … Removing most barriers to Chinese talent and capital would not undermine U.S. prosperity or national security. It would, however, make it harder for Beijing to maintain a growing economy that is simultaneously stable, self-reliant, and under tight party control. Compared with the United States’ current economic strategy toward China, which is more confrontational, restrictive, and punitive, the new approach would lower the risk of a dangerous escalation between Washington and Beijing, and it would prove less divisive among U.S. allies and developing economies. This approach would require communicating that Chinese people, savings, technology, and brands are welcome in the United States; the opposite of containment efforts that overtly exclude them. … If Washington goes its own way instead—perhaps because the next U.S. administration opts for continued confrontation or for greater economic isolationism—it should at the very least allow other countries to provide off-ramps for Chinese people and commerce, rather than pressuring them to adopt the containment barriers that the United States is installing.

What Posen wants to offer is the opportunity for individual Chinese and their families to vote with their feet. His suggestion that the West should open “off ramps” for Chinese seeking to opt out of the Cold War is telling - off ramps being a phrase more commonly invoked nowadays in Washington to discuss possible peace terms with Putin.

***

Thus, two pieces that are supposedly about the limit topic of disillusionment in business circles in China and China’s current economic difficulties, spiral into readings of world history.

The most radical assumption of all is encapsulated in the subtitle of Posen’s Foreign Affairs article, which boldly declares that what we are witnessing in China is the “Same old story”. One should linger over this apparently casual remark. Though passing for social scientific common sense, it is a staggering claim to make. One is tempted to say - paraphrasing Samuel Johnson - that when an analyst says about China, with a bored shrug, that is the same old story, they are probably done with intellectual life.

If it were true that anything about Venezuela or Turkey’s complex histories clearly anticipated that of China it should surely count, not as a confirmation of the some obvious piece of wisdom, but as a staggering and profoundly counter-intuitive discovery. These kind of comparisons again and again reveal the failure to grasp the sheer scale of the Chinese projects. This China that we are casually generalizing about, is a state whose population is the same as that of North America, South. America and all of Europe put together, under almost 80 years of uniquely transformative rule by a historically unique and still dynamic political party that directly inherits the DNA of the revolutionary era and self-consciously orientates itself towards avoiding the fate of the only regime to which it can, at a pinch, be meaningfully compared, namely the Soviet Union.

As Robert Harding put it very nicely in the FT a few days ago:

China’s economy defies analogies. Just as its growth over the past four decades was unprecedented, its current difficulties — and it certainly has a problem, if not quite a crisis — are unique. It is not Japan in 1990, Korea in 1997 or the US in 2008. (AT: let alone Venezuela, Turkey or Russia)

It may be true that parts of Chinese society are for a variety of reasons suffering a crisis of confidence, but precision is called for. Adam Posen and Li Yuan talk in general terms about “confidence” and credibility, but their narratives and evidence actually pertain to three different groups. Households are the center of the Posen story. Presumably the households that count are actually the affluent upper 25 percent or so, concentrated in Tier 1 cities, who are responsible for most spending and saving. Secondly, there are the corporate chieftains who not only toe the line, but whose businesses also have really big investment budgets that are easy for the regime to inspect. And then, the third group, the nameless group of “business owners” who are Li Yuan’s interlocutors. Presumably they are not so large that they must be seen to conform, but they are significant enough to attract the attention of a New York Times correspondent and be worth quoting.

Across these basic sociological divisions run questions of party membership, connection to provincial cliques and institutional connections to banks and other sources of funding. Those matter because what we in the end want to know is which of these groups is spending how much on consumption and investment and why. What kinds of things they are buying? What kinds of projects they are undertaking and how far this shows up in the macro data? If business confidence is shaken, what is the balance between large privates who are toeing the line and the mass of smaller private firms, where proprietorial dissatisfaction - expressed so graphically to Li Yuan - rules the roost?

Above all what we need to know to arbitrate the basic causes of the current malaise is how far depressed private business investment is in fact due to the kind of sectoral issues that Posen so quickly dismisses. Since property is the main store of household wealth in China, is this not likely to be the main driver of uncertainty, rather than views about Xi, the party and the capriciousness of their rule. Li Yuan’s piece is about the latest stimulus package and the stock markets so you would not necessarily expect a long discussion of the real estate crisis. But it is truly remarkable how little space Posen in his Foreign Affairs article devotes to the drama of China’s housing market.

At first glance this is doubly surprising because you might see the real estate slump as the single most important demonstration of the regime’s capriciousness. That is by all accounts how many property developers in China view the so-called “three red lines” policy that was announced in August 2020 at the peak of regime hubris. But before taking that interpretation at face value, ask yourself for a second how subprime mortgage lenders and dealers in MBS, or shareholders in AIG are wont to talk about the 2007-8 financial crisis. When tracking an unfolding economic crisis, who are the reliable informants? Whose opinions do we take at face value and whose do we take with a pinch of salt? Whose opinions matter because whether right or wrong they wield substantial power in the economy? Whose opinions can we discount on account of their powerlessness?

My bet is that Posen steers clear of discussing the housing crisis - overwhelmingly the most important source of uncertainty in the Chinese economy right now - because it causes problems of his argument. He knows that it does not fit his overarching thesis that the regime’s authoritarianism is the main source of risk for the modern Chinese middle class and that this by itself makes Xi’s regime incapable of ensuring sustained economic growth. At a technical level, as Michael Pettis explains, the figures for bank deposits that Posen cites to underpin his case, reflect both an increased rate of savings by worried households and a reallocation away from riskier assets, more closely associated with risks in housing. They are, in other words, an indicator of specific as much as general uncertainty. This is not to deny that the repressive tendencies and the ideological intent of the regime are a source of risk for private business and private individuals. Of course, they are. But the regime also offers advantages and protections. And those are not merely cold comforts. One cannot sensibly generalize about a downward spiral into an increasingly abusive relationship, as Posen’s narrative suggests. Sectoral performance is not a detail. It is all important. What is decisive is whether Beijing gets policy right and this reflects specific issues of policy and political economy that go beyond the simple boundary between public and private. These more complex balances of interests were decisive in the handling of COVID, of the real estate crisis, of the debt crisis, in the economic war with the US. They will be the topic of further installments to come.