D-Day 80 years on: World War II - Adam Tooze

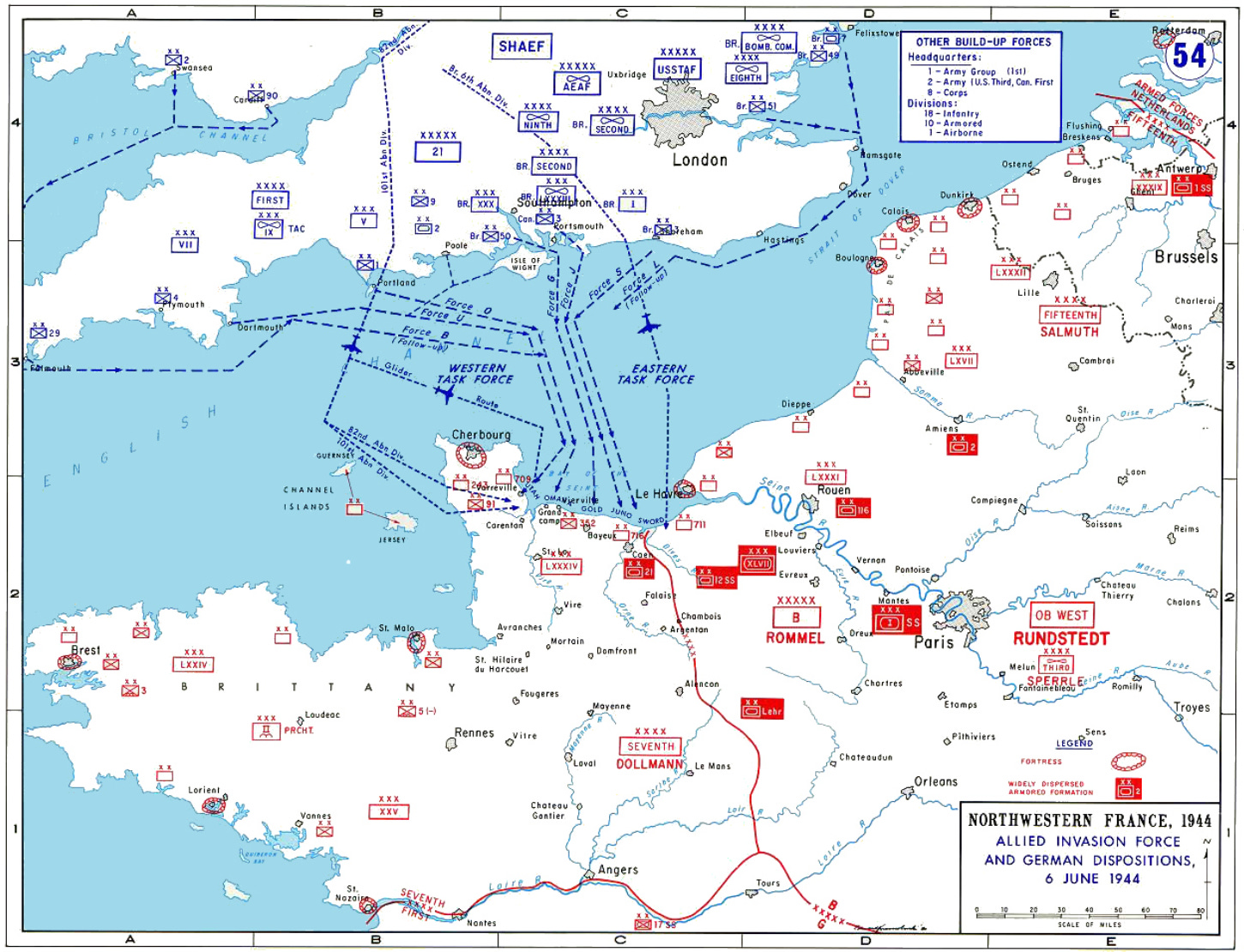

This week we commemorate the 80th anniversary of D-Day, 6 June 1944, when American, British, Canadian and French troops landed on five beaches along the coastline of Normandy in Northern of France to begin the liberation of Western Europe. Time was running out for the Empire that Hitler’s Germany had built in Western Europe after its staggering military victories in 1939-1941.

The rest of the world may be somewhat puzzled by this trip back in time, but for “the West” the 80th anniversary of “D-Day” is the perfect occasion for a rally. For the United States, France and the Commonwealth (the former members of the British Empire), D-Day is the decisive turning point in “our” World War II.

In June 1944 the landings had been a long time coming. After a series of crushing defeats between 1939 and 1942, the comeback of the British Empire and the USA in World War II began in North Africa in 1942 and continued in Italy 1943. But, it was the landing in Normandy in June 1944 that were the decisive breakthrough. The destruction of the German forces in Northern France opened the door to the liberation of Paris and to the eventual meeting with the Red Army in Central Germany in May 1945.

Many evenings, growing up in West Germany in the 1970s, my parents, who were children of wartime Britain, would tune in to the BBC World Service. The broadcast began then with a radio call sign that the BBC had used in World War II: “This is London” followed by an orchestral rendition of the 17th century tune Lillibullero (or Lilliburlero). Translated into morse code the opening bars sound out the “Victory V” - dit-dit-dit-dah. As a child, I imagined people across occupied Europe huddled around their radio sets listening for that tune, waiting for the moment of D-day to come.

That may seem like an extraordinary degree of nostalgia, but the war then was not ancient history. It was no further away than the late 1980s or early 1990s are for us today. Those wartime broadcasts were closer to us in the 1970s than the original release of Madonna’s greatest hits are to us today, or George Michael singing “White Christmas” in 1984, let alone Abba.

That memory, so close and so far, stirs in me still. And it troubles me.

What troubles me now is how this “legendary” history of World War II continues to operate at the heart of Western political ideology. How it is used, 80 years later to frame and shape our understanding of a radically different world. What I struggle with is how to frame a historical understanding of the war that wrenches it out of this framing, that is not saccharine, that is not nostalgic that is not atavistic, but speaks in more challenging and eye-opening ways to the present.

I’ve been thinking about this for a while. And I want in this mini series to pull together some pieces through which to approach this question.

What is surprising is that almost 80 years after the defeat of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan the history of World War II is still a live historical and ideological reference point. In Russia and China, victory day is still commemorated with true pomp and ceremony. The horrors of the period - whether the Holocaust, Soviet violence, mass bombing, the Bengal famine, or Japan’s atrocities in China and Korea - shape memory and trauma culture down to the present day, in different ways.

In an odd twist of history, World War II has been markedly more present during Joe Biden’s Presidency than it was under either Trump or Obama. It may have something to do with Biden’s age. The American President was born in November 1942, 18 months before D-Day, when the battle of Stalingrad was still raging.

But it is not just personal nostalgia that is at stake here. Biden’s references to World War 2 are also programmatic. They go hand in hand with his emphatic revival of Atlanticism and bold claims to American leadership in a struggle of democracy v. autocracy.

As Biden travels to France this week, in some corners of US media, the D-Day anniversary is already generating a bow-wave of rhetorical enthusiasm. The NBC headline blares:

Which dictators does Biden have in mind? Foreign powers for sure. But in 2024 it is first and foremost the United States itself that is at stake. As NBC’s Peter Nicholas blithely continues:

“In the background of the president's trip to France this week will be his rematch against Donald Trump, who questioned some of the pillars of the post-World War II order. … President Joe Biden leaves the campaign trail this week and flies to France for the 80th anniversary of D-Day, where he’ll give speeches touting American alliances that beat back dictatorships bent on world conquest. Biden is in a long string of presidents who have delivered that sort of message over the years as they built and sustained a Western bloc rooted in free markets, democratic governance and individual freedoms.”

And then comes the zinger:

“As yet unknown is whether he'll be the last. The race between Biden and Republican Donald Trump is a toss-up at this stage, and if Trump returns to power, there are no assurances he would keep the basic pillars of the post-World War II order intact. As president, Trump considered pulling out of the NATO alliance, which has been a bulwark against Russian aggression since the depths of the Cold War … A senior Trump White House official said in an interview that Trump came within a "wisp" of dropping out of NATO at a summit meeting in Brussels in 2018. More recently, Trump said he would let Russia to do "whatever the hell they want” to European countries that didn’t spend enough on military defense.”

And other members of the Washington foreign policy establishment chime in no less unequivocally:

“This is a very important opportunity for President Biden to reaffirm our NATO alliance and emphasize that the world is really on the cusp of a turning point,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., a member of the Foreign Relations Committee. “We are living through the middle of the fight for democracy and freedom over authoritarianism.”

Clearly, D-Day as a pillar of historical memory, helps to anchor a conventional understanding in the Washington establishment of what American world leadership should look like.

The use of World War II and in particular the Normandy landings in this way has its own history. The first major collective commemoration of D-Day took place in 1984 at the instigation of French President François Mitterrand. The early 1980s were a tense moment in the final phase of the Cold War. Normandy was a stage that both Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan relished. And the Biden team clearly know this.

Biden will speak twice in Normandy this week, first on Thursday, the anniversary of the beach landings and then again, on Friday at Pointe du Hoc, where U.S. Army Rangers scaled cliffs to knock out a German gun emplacement and where Ronald Reagan spoke in 1984, giving a then-famous speech which culminated in the line: “These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc.” As NBC reminds us, Reagan went on to win re-election by a landslide.

The 1980s were also the moment when Holocaust consciousness became profoundly influential in Western politics on both sides of the Atlantic. As Reagan’s speech suggests this gave World War II a new significance. Fighting the Nazis became a matter of fighting a murderous anti-semitic regime. In Biden’s fierce attachment to Israel, we see echoes of that revival of Holocaust memory that impacted his generation profoundly.

Commemorating D-Day in this way is ironic in two ways.

First the United States and the British Empire were fighting a war in 1944 not as members of a NATO alliance, defined by “Western values”, but in alliance with Stalin’s Soviet Union and China. The commitment of resources to Normandy meant deprioritizing the war in Asia, where China - both its Nationalist and Communist wings - was playing a key role in draining the Japanese military. Meanwhile, in Europe D-day would simply never have been possible without the huge weight of casualties inflicted by the Red Army on Germany’s military. A staggering 80 percent of the battle casualties of the Wehrmacht were inflicted not in the West but on the Eastern Front (Overmans). Arguably a more important anniversary in military terms than D-Day will be 80th anniversary of the destruction of Germany’s Army Group Center in Operation Bagration launched by the Red Army on 22 June 1944.

The new memory politics of D-Day shaped since the 1980s is ironic also, in that nowhere in the calculations that motivated D-day did the Holocaust feature. In 1944, the Western Allies were not fighting Nazi Germany to stop the Holocaust. They showed scant regard for the Jewish representatives who pleaded for earlier action or bombing of the camps. Stalin’s demands for a “Second Front” and the advances of the Red Army were a factor in the calculations of Churchill and Roosevelt. The fate of the Jews was not. The first concentration camp to be liberated was Majdanek near Lublin in Poland in July 1944. Not until 1945 did the Western allies begin to wake up to the full horror of the Nazi regime and all the way down to the present day there is a tendency to insist that the war in the West was different and “clean”.

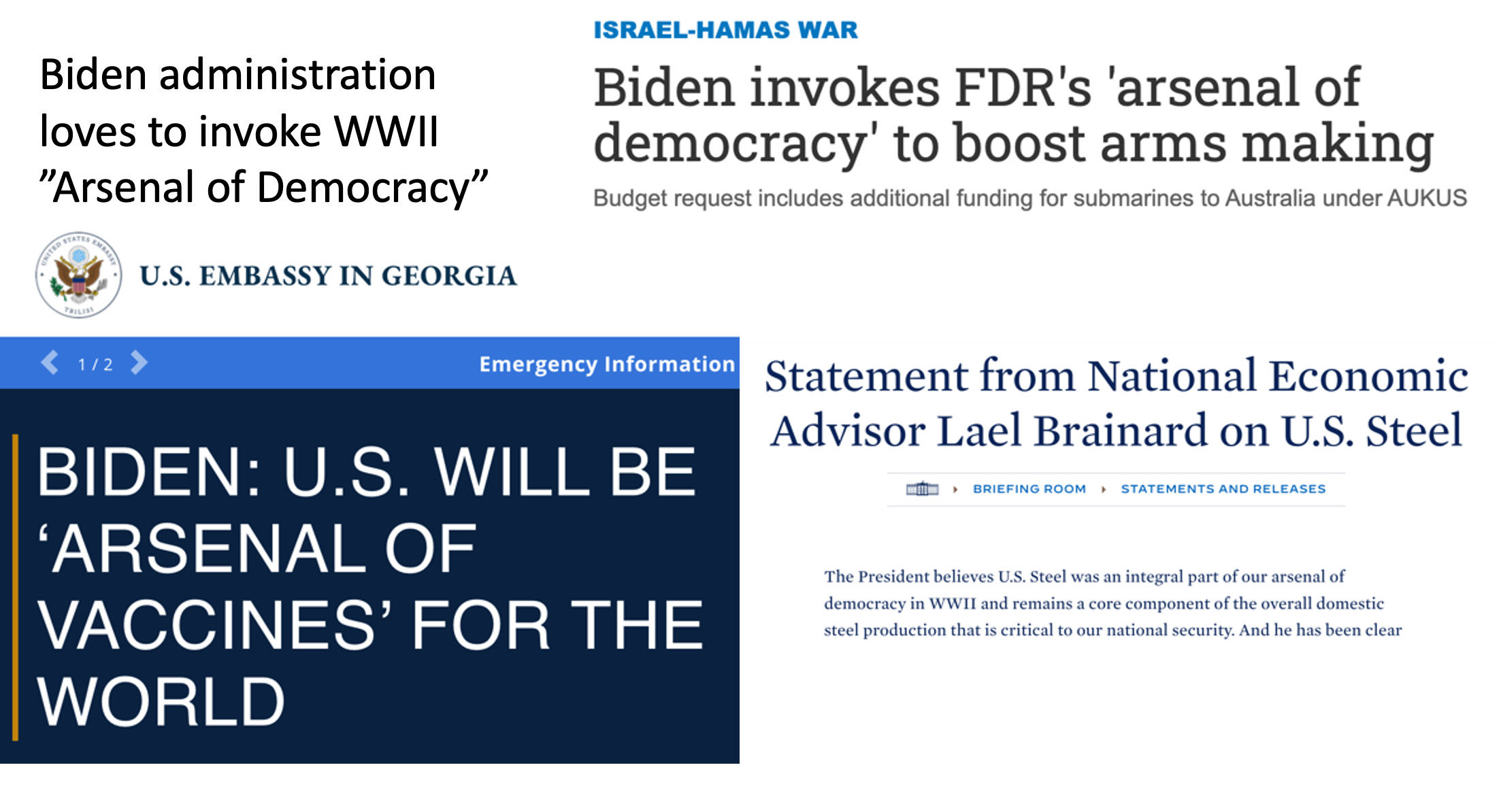

The other way in which World War II is notably present for President Biden is in his many evocations of the “arsenal of democracy”.

The other way in which World War II is notably present for President Biden is in his many evocations of the “arsenal of democracy”.

Nor is this reference limited to the Biden administration. The enthusiasm for FDR's industrial rearmament after 1940 helped to fire the original Green New Deal back in 2018. If the United States could turn itself into a giant mass producer of military aircraft, why should it not be able to pull off the green energy transformation?

Far from this being a passing phase, to my surprise this same narrative recurs full blast, in the spring of 2024 in Stephanie Kelton’s new documentary, “Finding the Money”. It features an extended section on how generous financing enabled the World War II production miracle complete with the inevitable footage of bombers rolling off Fordist production lines.

Certainly, D-Day was nothing if not a display of the massive force assembled by the arsenal of democracy. That will be a basic theme of this mini-series: modern war as mobilization. But once again there is an ambiguity in this simplistic celebration of the US-led Western war effort as an inspiration for progressive politics in the 21st century.

The first point is that the more material is mobilized, the more we flaunt productive power, the more we downplay the role of the fighting men on the frontline. Materialism cuts against heroism. The US Army Rangers scaling the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc were fighting with great bravery, but they had behind them a truly staggering arsenal. Nor was this an accident. The Western way of war, exemplified by D-day put firepower above manpower wherever possible. This is how rich democracies fight if they can. Those who suffer horrendous casualties are, almost by definition, either poor or desperate.

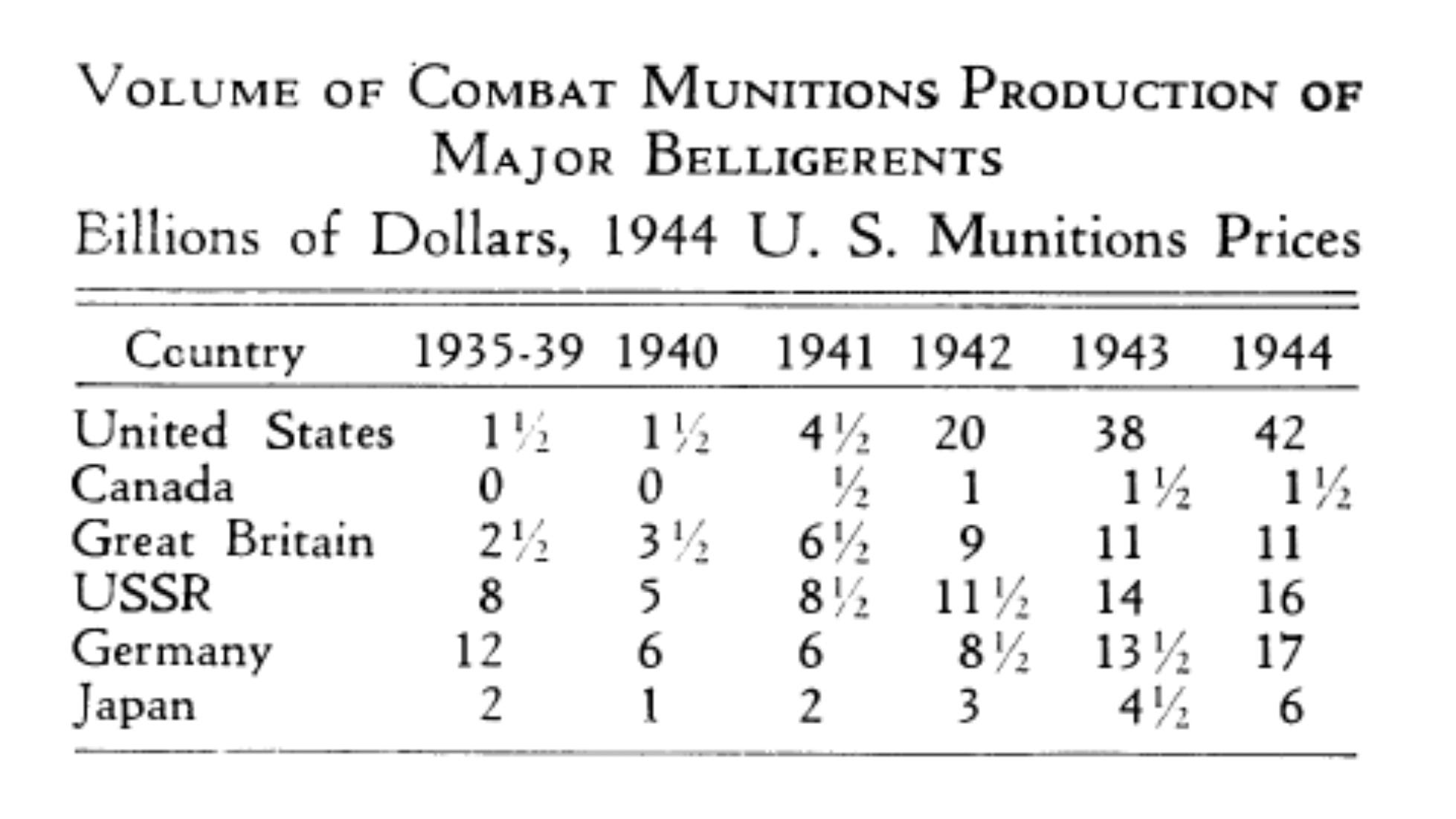

Furthermore, for all the productive achievement of the USA during World War II, America’s output was no miracle. The US produced what you would expect from a highly productive industrial economy, coming out of a deep recession with ample underemployed resources, liberally provided with purchasing power. Over the period 1939 to 1944, the ratio of armaments production in the Allied coalition to that in the Axis corresponds broadly speaking to the ratio of GDP and steel production. If there was a productive “miracle” in World War II it was not to be found in the West, not in Britain, the United States or Germany, but in the Soviet Union.

Source: Goldsmith, “The Power of Victory” (1946)

The really remarkable achievement in this table compiled by Goldsmith, Director of Economics at the US War Production Board, were not the American numbers, but the fact that in the critical years of 1942 and 1943 the Soviet Union outproduced Nazi Germany. And it was not just a matter of quantity. Soviet weapons production was not just gigantic in scale it was also good. Detroit, for all its productive prowess, never produced a tank that could compare with the T-34 or JS series.

But apart from correcting US hubris what is the significance of these numbers for us today? This surely is the deepest irony and unsettlement of any serious thinking about World War 2. What we celebrate when we celebrate the wartime economies of the Allies is the concentrated and massive deployment of material and energy for the vast production of means of destruction and not just for the production of those tools of war. The entire conduct of the war was based on the vast deployment of energy. The Allied armies, most notably at D-day, were swimming in oil. Never before had a war been as motorized or as dependent on hydrocarbon fuels.

From the vantage point of the 21st century, if there is a historical grand narrative that does justice to the significance of World War II, you could claim that it is is the question of global political organization, NATO etc. This was indeed new. To call the global blocs that emerged after 1945 “empires” is to lack historical imagination. The Cold War blocs were newfangled assemblages of power based on a far more self-conscious articulation of global ideologies, economic development and military power than any empire had ever delivered. Certainly nothing the Europeans had established in the 18th or 19th centuries came close to measuring up. Crucially, in a stark contrast to the experience after World War I, wartime models of production and organization were continued into the aftermath of 1945.

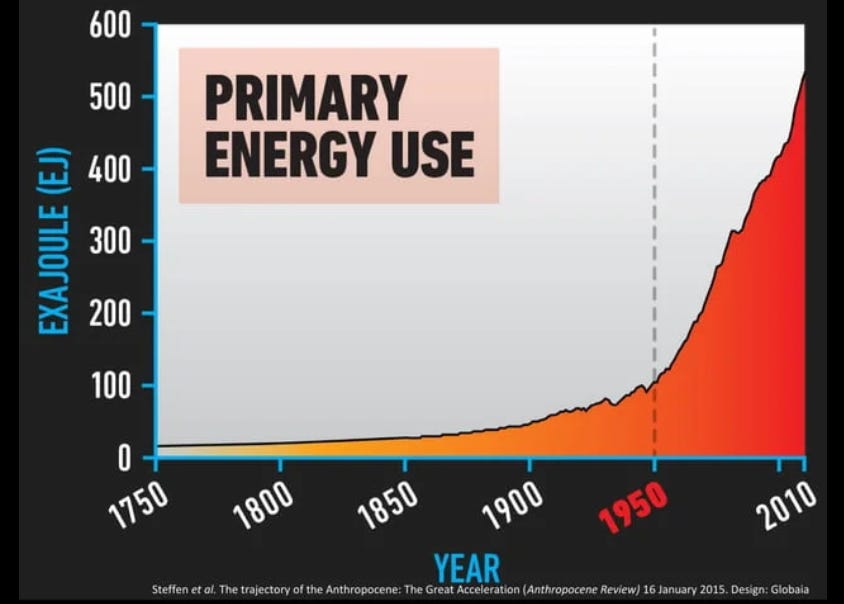

The most important manifestation of that continuity of mobilization was in the field of energy. World War II gave birth both to the atomic age and the widespread adoption of oil as a key driver of economic growth after 1945. Allied victory and postwar affluence were based not just on their superior political and social organization but on their vastly greater mobilization of natural resources. And from the vantage point of the 21st century this after all is what Bidenomics and the Green New Dealers are gesturing to in their enthusiasm for the 1940s moment. What connects us to that historical moment is what environmental historians call the “Great Acceleration,” the vast and dramatic acceleration of humanity’s appropriation of nature that reached a turning point in the middle of the 20th century.

In its globe-spanning dimensions, in its multifaceted integration of the land, the sea, and the air, and in its violent intensity, World War II was the launching point for the Great Acceleration, a giant process of mobilization that continues down to the present day.

Not for nothing Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz in their remarkable work The Shock of the Anthropocene propose the term the Thanatocene to describe this melding together of material mobilization and war.

If the Anthropocene is the idea that humanity as a whole has become a force reshaping the planet in geological terms, the Thanatocene captures the way that war-fighting has animated that process and given it extra force.

One can think of this as exemplified by the extraordinary armies mobilized by the Allies for the invasion of Normandy, but this collapses what were in fact three different modes of war-fighting that came together to make World War 2 the extreme event that it was.

The first was the gigantic clash of land armies and accompanying tactical air power that culminated in the huge campaigns of World War 2. It was preeminently the war waged between the Wehrmacht and the Red Army, and it was out of that furnace that the Soviet military emerged as the most formidable land army the world had ever seen. It founded Soviet domination across Eastern Europe and into the Far East, crushing the Japanese empire in Manchuria as an afterthought in August 1945. This stood in a tradition that extends back, by way of the great struggle with Napoleon, to the emergence of Russia as a modern military power under Peter the Great. The Normandy campaign - both the landings and the subsequent break out across France - are arguably the only moment when Western war-fighting, that is war-fighting by Britain and the United State, ever approached the scale and drama of this mode of war. It involves a gigantic logistical effort about which I will have more to say in this mini-series.

The second type of warfare on display in World War II was colonial and racial war, wars like those waged by Italy in Africa from the 1930s, Japan in China and Nazi Germany in the Soviet Union. This involved a project of occupying territory and remaking its population. It was settler colonialism backed by a level of military force never before seen. In the face of an emerging discourse of racial equality and rights, it ostentatiously and explicitly flouted their disregard, insisting on the central significance of racial distinction and hierarchy, up to and including enslavement and genocide. This war would reshape the ethnic map of Europe and do gigantic damage in Asia. As I outlined in an Chartbook 258 earlier this year the remaking of the map of the Middle East and the formation of the Western-sponsored state of Israel were part of that process of territorial and demographic rearrangement that also included the ethnic cleansing of over 12 million Germans from Eastern Europe after 1945.

But the war witnessed not only this savage form of state-making, but also its opposite, a new type of revolutionary anti-colonial warfare, based above all in a mobilized peasantry. The Chinese Communist Party under Mao Zedong would lay claim to this tradition. But it had its counterparts in the war against Germany waged by Soviet partisans and Josip Broz Tito’s Partisan armies in Yugoslavia. After 1945, it would remake large parts of Asia and Africa. I’ll return to this in a future post in this series.

Mao spoke metaphorically of guerilla fighters operating like fish in water. But the actual fighting at sea as in the air was reserved by the 1940s for the richest combatants. This is the third dimension of World War II as a physical confrontation. Alongside conventional land war, and colonial and guerrilla struggles, the air war and its close relative, the naval blockade, were the quintessential expression of a hypermodern mode of warfare, in which Britain and the United States, more than any other combatants invested the largest part of their war efforts. By the end of the war, the British and Americans could project force literally around the planet. Huge convoys of ships could carry tens of thousands of soldiers and their equipments across Oceans. Fleets of over a thousand aircraft guided by electronic beams carried thousands of tons of bombs to targets in Europe and Asia. This war unleashed new forms of horror including the incineration of cities from the air. And the bombing was appallingly indiscriminate. In the bombing ahead of D-Day in 1943 and 1944, British and American bombers killed at least 50,000 French civilians. This almost certainly exceeds the number of French civilians killed by the German occupation authorities other than in the resistance.

Air war in particular was vastly expensive, accounting for forty percent or more of the economic war effort of the Germans, Americans or British. By the end of the war, aerospace industries were the largest sectors of the industrial economy and remade entire regions with new factories and workforces. Out of this gigantic effort was born the technology of modern logistics, radar and sonar, a new generation of aircraft with jet propulsion, and the Manhattan Project. Meanwhile, Germany’s vain effort to find an answer to the West’s air power gave birth to ballistic weapons programs. By the end of the war, cameras mounted on the tips of captured German V-2 rockets fired vertically upward rather than at London or Antwerp provided the first glimpses of the outer edge of the atmosphere and the curvature of the Earth. The war thus literally transformed the way that we see our planet as is captured in this extraordinary newsreel from 1946.

The landings in Normandy in June 1944 concentrated these many facets of modern war. Starting there I want in this series to look at different facets of the way in which war functioned as an accelerator of the great acceleration and how we think and commemorate that process. Posts will include the new modes of war-fighting in the West, the logistical and mechanical base of the war - Jerricans, bulldozers - and other modes of modes of war-fighting.