WWI is clearly the “Urkatastrophe” - the original catastrophe - of the 20th century. Not just of the short twentieth century, from 1914 to 1991, but of the long twentieth century too.

1914 is in the news again today as a way of understanding the mounting tension between China and the United States. In this historical analogy, the United States, the incumbent, is allotted the role of the British Empire, seeking to resist the challenger, China, which is placed in the position of the Kaiser’s Germany. (Btw: Apart from the weirdness of this analogy, it also assumes a pretty strong and contentious thesis on what actually happened in 1914. More on this another time.)

The line you take on the outbreak of the war in 1914 colors your entire vision of European and world history. One way of describing the situation is simple. In the words of my good friend Alexander Zevin, as quoted by Perry Anderson: ‘The structural reality is that the First World War took place over empires, for empires and between empires’.

A clash of Empires, for sure. How could it have been anything else? After all, all the great powers at the time were one or other type of empire. To add any value we need to be more precise in defining the historical conjuncture. 1914 was not simply a clash of Empires. The war was a product of a distinct conjuncture, well-labeled as the ‘age of imperialism’ . This conjuncture was defined not simply by empires butting up against each other, as they had for centuries. It was a new epoch defined by a new blend of expansive geopolitical claims, empires dynamized by nation-state mobilization at their core and the imbrication of those states with the interests of the latest generation of capitalist accumulation. All of this took place against the backdrop of a vision of history and global geography that was both grand and claustrophobic. The global frontier closed in the 1890s. The stage was set for the great play of world history to begin in earnest.

Nor was this lost on contemporaries. The wide currency of imperialism theories dates to the moment of the Spanish-American war and the US invasion of the Philippines (1898-1899), the Boxer intervention (1899-1900) and the Boer War (1899-1902). The notion comes in different shades, ranging between J.A. Hobson’s liberal version to Lenin’s Bolshevik classic.

Lenin’s analysis, like that of Rosa Luxemburg before him, is more holistic and deterministic than that of Hobson. They have in common that they described the current moment of imperialism as something new.

The age of imperialism was clearly the final stage in a Western drive to expansion that began in the 15th century. It also continued the history global competition, which in the case of Britain and France went back to the 18th century. But in the late nineteenth century, this took on a radical new expansiveness and violence. Crucially, because it was now conceived of as taking place within a finite sphere. The frontier was closed and because the pressure of historical time and drama speeded up. The German phrase, Torschlusspanik, is apt.

In this remarkable interview, the South African artist William Kentridgedefines it as:

The panic of closing doors. The fear of opening one door rather than another, and hearing it slam behind you, once you have made your decision; but maybe that decision is the wrong one, so you would rather stand paralysed in front of three doors to avoid making it. Torschlusspanik.

William Kentridge in interview with Peter Asden, “The art of war” for The Financial Times, 7/8 July 2018.

In 1959 the publication of William Appleman Williams’s Tragedy of American Diplomacy, and in 1961 Fritz Fischer’s Griff nach der Weltmacht, gave imperialism theory a new lease on life in the historical profession.

Amidst the general resurgence of imperialism-talk in the context of Vietnam and Third World struggle, Fritz Fischer’s Germano-centric account of 1914 produced an extraordinary éclat. But as far as the July crisis of 1914 was concerned this was also the last great hurrah of imperialism theory. The critical onslaught against Fischer’s interpretation of the outbreak of the war helped to discredit models of imperialism more generally. It did not help that Fischer’s take on German responsibility got caught up with crude Sonderweg models that tried to identify the supposed abnormalities of Germany’s modernization. This involved tying undeniable and important differences in political organization, military command chain and strategic outlook to subtle and much harder-to-define national social-structural differences. It was an intellectual dead end. What got lost in the process was any awareness of the broader development both of global capitalism and imperialist competition.

By the 1990s, whether or not historians have ascribed responsibility for the July crisis to Germany, the focus has shifted away from a broad-based analysis of imperialism (and the Sonderweg) to one based on politics, diplomacy, the arms race and military culture. Often this is associated with a stress on the July crisis as an event determined by the continental logic of Central Europe rather than the wider forces of global struggle - the scramble for Africa or imperial tension in Asia - that seemed to be implied by references to imperialism.

Economic forces continue to play a key role in any plausible interpretation of World War I - in the form of Russia’s looming development and the costs of the arms race between the major power. But whereas under the sign of imperialism theory the link from geopolitical ambition to economic interests was made scandalously explicit, in more recent work the underlying economic dynamics are no longer foregrounded . The tight connection between the outbreak of war, imperial expansionism and capitalist competition has unravelled.

If conventional historiography displaced imperialism and the discussion of capitalism from the center of the discussion, economists and economic historians were only too happy to concur. British economic historians of empire were in the vanguard of the academic attack on the first generation of imperialism theories. They never liked Lenin.

The body of work on the 19th-century world economy that emerged in the 1990s, notably that jointly authored by Kevin O’Rourke and Jeffrey Williamson, treated the period before 1914 under the rubric of globalization, rather than imperialism. Theirs was not a panglossian history of globalization. Loosely following the model offered by Karl Polanyi’s classic The Great Transformation (1944) they focused on social tensions unleashed by mass migration and the grain invasion in Europe, which collapsed commodity prices and hurt the rural interest. But war lay outside their purview. 1914 was exogenous. Sarajevo appears as a nasty accident.

In 2007 the Communications Director of the IMF remarked ruefully: “Alas a sniper's bullet on June 28, 1914, triggered a chain of events that reversed globalization.” Indeed, pushed to the limit, the neo-Polanyian school of economic history could be read as arguing that to understand the crises of globalization that arose in the early 20th century, you did not need the exogenous shock of World War I at all. Counterfactually, the “interwar crises” might well have happened even without the wars.

It is strong stuff!

Crucially, monopolies and militarism were not seen as constitutive of globalization, as imperialism theory à la J.A. Hobson would have it, but as antithetical to globalization. As Williamson and O’ Rourke put it with characteristic frankness, in their calculations of market integration they assume that ‘(i)n the absence of transport costs, monopolies, wars, pirates, and other trade barriers, world commodity markets would be perfectly integrated’. Globalisation, by their measure, would thus be complete if only power and politics did not get in the way. The fact that imperial rivalry actually led to major investments in transport infrastructure and enabled globalization is excluded by assumption. Likewise, there is little room for acknowledging the way that large-scale foreign lending - on the basis of an increasingly integrated capital market - supercharged the imperialist aggression of a rising power like Japan. Whilst “domestic” socio-economic stresses are admitted, economics and geopolitics are held at arms length.

An economics squeamish about the question of power converged with an anti-Leninist historiography to squeeze out the question of imperialism and 1914.

Whatever one thinks of the political and intellectual lineage of imperialism theory, this is obviously problematic. A useful theory of globalization must account for global conflict as endogenous to the process of global growth, rather than exogenous.

My book Deluge sought to capture one element of that shift - the dramatic rise of the United States. For that reason it started, provocatively, in 1916.

But, conscious of the need to face the “1914 question”, I addressed the question of the politics and economics of the war in a trio of essays that appeared at the same time as the book.

An essay with Ted Fertik queried whether WWI was really a break in the trajectory of globalization or could instead be seen as a phase in which globalization was rearticulated in violent ways.

Another, argued not that WWI was a war of democracy v. autocracy, as Entente propaganda had it, but a war fought under democratic conditionsover what democratization might turn out to be in the 20th century.

I will come back to both those arguments in later posts.

Most pertinently, I contributed an essay to a volume edited by Alex Anievas explicitly on the question of “Capitalist Peace or Capitalist War? The July Crisis Revisited”. A full draft can be downloaded here.

| Adam Tooze Political Economy And The Jul... 570KB ∙ PDF File |

|

You can find at least some of the footnotes necessary to support the following sketch argument in that pdf.

Even within the sphere of mainstream academic social science, it is striking that compared to history or economics, political science has been far bolder and more interesting in advancing ways of explicitly connecting economics, politics and war. In arguments over the theories of “capitalist peace”, “democratic peace” and bargaining theories of war, economic development, or the lack of it, is tied to 1914. The PDF article discusses some of those debates as they stood around the anniversary in 2014.

In this newsletter I want to make a more streamlined version of that argument.

The key points are as follows:

The firewall drawn between “1914” and the story of the first globalization is ideological. But it is also a weak form of ideology - a silence rather than a strong thesis. Mainstream historical accounts of the July crisis in 1914 are, in fact, based, more often than not, on a modernization theory that dare not speak its name. Accounts such as Chris Clark’s Sleepwalkers rank Western European Empires and the scrappy Balkan protagonists in developmental terms. Meanwhile, economic accounts of the late 19th century that give a civilian-socio-economic analysis of the stresses of globalization and treat 1914 as exogenous, result not just in a whitewashing of global economic development, but in strange and counterfactual history of the early twentieth century.

Uncoupling geopolitics from socio-economic development is a problem not just for our understanding of 1914, but for the interwar period that follows. Not only is 1914 exogenized but you end up, for instance in Barry Eichengreen’s work, with an account of the interwar period to which the war itself is causally incidental. As I will argue in a future note, this points to a broader problem of articulating global power politics with international economic history in the early 20th century.

In light of all this evasiveness, we should bring the concept of an age of imperialism back.

In a remarkable article published in 2007, Paul Schroeder the doyen of European diplomatic history, asked how are we to characterise the sea-change that had clearly come over the international system in the generation before 1914. The world that the modern political science literature takes for granted, of multi-dimensional, full spectrum international competition was not a state of nature. It had taken on a new comprehensive form in the late nineteenth century. There is still no better concept, Schroeder insists to grasp this competition that embraced every dimension of state power –GDP growth, taxation, foreign loans – that made the constitution of Russia itself endogenous to grand strategic competition, than the concept of an ‘age of imperialism’. Schroeder is not, of course, appealing for a return to Lenin. But what Schroeder wishes to highlight is what it was that Lenin, Kautsky and other theorists of the 2nd international were trying to analyse and rationalise; namely the widely shared awareness that great power competition had become radicalised, expanded in scope, and had taken on a new logic of life and death.

In this view of the age of imperialism the driver is not the competition of individual capitalists, harnessing nation states for their purposes, with Krupp or Vickers Armstrong, or Cecil Rhodes in the driving seat. The notion of imperialism that Schroeder invokes and I would subscribe to, is more general and ultimately framed by state power and politics. As far as the economy is concerned the key is the global balance of (geoeconomic) power, both as a specific construct - number of guns etc - and as a frame for thinking about the world. This links to my early work on the history of statistics. It is against the backdrop of the age of imperialism that both the concept of national economy and, as Quinn Slobodian has shown, the idea of the “Weltwirtschaft” take shape. We enter, in short, the world of mental mapping that we still inhabit today, the mapping that causes us to ask: when China will overtake the United States as the world’s largest economy?

The basic point to be made about global economic growth before 1914 in connection with the outbreak of the war, is that it was uneven. Some national economies grew faster than others. This uneven economic development threatened to shift the military balance of power, by way of manpower, tax revenue and technological capacity as well as strategic assets like railways. And it was that which was a prime driver of the tensions and calculations that lead to war in 1914.

Furthermore, this competition should not be understood merely in objectivist terms - the numbers of troops and speed of railways etc. If we want to understand decision-making we also need to grasp the way in which those differences were made sense of. How they fitted into visions of the present and the future. How they were framed as part of the great drama of world history.

The logic of rivalrous uneven development played out in distinct force fields.

The one most commonly invoked for purposes of historical analogy is Imperial Germany’s rivalry with Britain. This was no doubt serious. It could, at various points have lead to conflict. But, as far as the war that actually broke out in 1914 was concerned, it was an indirect contributor. By 1914, Britain had clearly won the naval arms race. It had sone so, not through superior industrial performance, but through strategic focus, determined technological development and the success of the Liberal government in forcing through a constitutional and a fiscal revolution. Britain had the tax base to compete.

The military-industrial race that directly impelled the outbreak of war in 1914 was not naval but continental and it was not, in fact, one race, but two.

The decisive axis was France-Germany-Russia. This revolved around the relative mobilization of national resources by France and Germany and the sporadic and unpredictable development of Russia. Russia was truly the swing variable.

Russia was defeated by Japan in 1905 and had been shaken by revolution. On the other hand its huge size and enormous potential made it a looming threat as far as Germany and Austria were concerned. The Tsar and his ministers had huge freedom of action. It had a neutered parliamentary system. In Russia’s governing circles politicised nationalist protectionism was rampant. Added to which, with ample funding from France, Russia’s power was growing by the year and its expanding railway network was speeding its pace of mobilization. In the summer of 1912 Jules Cambon of France noted after a conversation with Germany’s Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg that regarding Russia’s recent advances,

the Chancellor expressed a feeling of admiration and astonishment so profound that it affects his policy. The grandeur of the country, its extent, its agricultural wealth, as much as the vigour of the population … he compared the youth of Russia to that of America, and it seems to him that whereas (the youth) of Russia is saturated with futurity, America appears not to be adding any new element to the common patrimony of humanity.

The French themselves were extremely optimistic about Russia’s prospects. A year later French foreign minister Pichon received from Moscow a report commenting that

there is something truly fantastic in preparation, …. I have the very clear impression that in the next thirty years, we are going to see in Russia a prodigious economic growth which will equal – if it does not surpass it – the colossal movement that took place in the United States during the last quarter of the 19th century.

Was Russia a bankrupt? Or was it a steamroller?

In 1913 the Kaiser’s government finally persuaded the Reichstag to agree to raise the size of peacetime army from 736,000 to 890,000. But the immediate response was to triggers the passage of the French three year conscription law and the promulgation of Russia’s ‘Great Programme’, which raised its peacetime strength by 800,000 by 1917. By 1914 Russia’s army strength was double that of Germany and 300,000 more than that of Germany and Austria combined with a target by 1916 of 2 million. Against this backdrop the Germans were convinced that by 1916–1917 they would have lost whatever military advantage they still enjoyed. This implied to them two things. First, Russia would be unlikely to risk a war until it reached something closer to its full strength. So Germany could risk an aggressive punitive policy in Serbia. If this containment were to fail, then 1914 would be a better moment to fight a major war than 1916 or 1917.

But, no more than Anglo-German competition, was it a direct confrontation between France, Germany and Russia that triggered war in 1914. The stakes were too high for an open clash to happen there.

What launched the war was a clash between their allies in a third zone of competition - the shatter-zone of the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires. The basic question that dominated the rivalry between the Balkan powers and their great power backers was the question of backwardness. This was in part political and military but it was also, crucially, economic. These were the poorest parts of the European economy. Could they catch up? Did any of them, the Bulgarian, Serbians, Austrians or the Tsarist Empire, actually have a place in the 20th century?

In a very general sense this three-sphere model: Anglo-German, Franco-German-Russian, Habsburg-Serb-Russian can clearly be ranked in terms of economic and political development.

But that neat hierarchy is muddled by the fact that the logic of alliances dictated not separation of hierarchical levels but interconnection. For progressives in France and Britain, those who believed most firmly in the logic of progress, it was profoundly disturbing to find themselves from the 1890s onwards, drifting towards a strategic alliance with Tsarist Russia.

On grounds of liberal political ethics an alliance between the French republic and the autocratic and anti-semitic regime of Tsarist Russia was clearly to be regarded as odious. But furthermore, if as liberals insisted, the domestic constitution of a society was predictive of its likely international behavior and its future prospects, then an alliance between a republic and an autocracy was questionable not merely on normative liberal, but on realist grounds. For a convinced liberal placing a wager on the survival of the Tsarist regime was a dubious bet at best. Tsarism’s army was huge and it was convenient to be able to count on the Russian steamroller. But could Tsarism really be relied upon as an ally? Might Tsarism not at some point seek a conservative accommodation with Imperial Germany? Furthermore, given liberals understanding of history, was the Tsar’s regime not doomed by its brittle political constitution and lack of internal sources of legitimacy?

Following the defeat at the hands of the Japanese and the abortive revolution in Russia in 1905, Georges Clemenceau, an iconic figure of French radicalism before his entry into government in 1906 was particularly prominent in demanding that France should not bankroll the collapsing Tsarist autocracy. From Russia itself came pleas from liberals calling on France to boycott the loan to the Tsar. Poincaré typically cast the problem in legal terms. How was Russia to reestablish its bona fides as a debtor after the crisis of 1905? If Russia was to receive any further credits it must provide guarantees of their legal basis. That would require a constitution, precisely what the Tsar was so unwilling to concede. Meanwhile, France’s own democracy suffered damage as Russian-financed propaganda swilled through the dirty channels of the French press. The most toxic product of this multi-sided argument were the notoriously anti-semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion a forgery generated by reactionary Russian political policemen stationed in Paris, who were desperate to persuade the Tsar that the French-financed capitalist modernisation of Russia was, indeed, a Jewish plot to subvert his autocratic regime.

But the demands from French Republicans and Russian radicals were, in fact, to no avail. The international system had its own compulsive logic that might be modified but could not so easily be overridden by political considerations, however important they might be. The consequences of Bismarck’s revolution of 1866–1871 could not be so easily escaped. By the 1890s the triumphant consolidation of the German nation-state had created enormous pressure for the formation of a balancing power bloc anchored by France and Russia. This type of peace time military bloc might be a novelty in international relations. It might be odious to French radicals. But Tsarism knew it was indispensable. By 1905, Russia was too important both as a debtor and as an ally to be amenable to pressure. With the French demanding that foreign borrowing be put on a secure legal basis and the Duma parliament uncooperative, the Tsar’s regime simply responded by decree powers arrogating to itself the right to enter into foreign loans.

Desperate to escape this dependence on Russia, French radicals looked to the Entente with liberal Britain. Clemenceau indeed risked his entire political career in the early 1890s through his adventurous advocacy of an Anglo-French alliance, laying himself open to allegations that he was a hireling of British intelligence. And certainly some British liberals, Lloyd George notable amongst them, understood the 1904 Entente with France as a way of ensuring that there would be no war between the two ‘progressive powers’ in Europe. But Britain’s own concern for its imperial security was to pressing for it to be able to ignore the appeal of a détente with Russia. It was the hesitancy of the British commitment to France that combined with the Russian revival to push Paris back in the direction of Moscow. By 1912 the French republic was committing itself wholeheartedly not to regime change in Russia but to maximising its firepower.

The appeal of the ‘liberal’ British option was not confined to France. In Germany too the idea of a cross-channel détente with Britain was attractive to those on the progressive wing of Wilhelmine politics. Amongst reformist social democrats there were even those who toyed with the idea of a Western democratic alliance against Russia, including both France and Britain. Bernstein reported that when he discussed the possibility of a Franco-German rapprochement with Jaures, the Frenchman had exclaimed that in that case France would lose all interest in the alliance with Russia and the ‘foundations would have been layed for a truly democratic foreign policy’. Beyond the ranks of the SPD, ‘Liberal imperialists’ speculated publicly about the possibility of satisfying Germany’s desire for a presence on the world stage, without antagonising the British. But in practice the Kaiser and his entourage, no doubt backed by a large segment of public opinion, could never reconcile themselves to the reality that they would forever play the role of a junior partner to the British Empire. Antagonism with Britain, however, implied an alliance system that bound Germany to the Habsburg Empire as its main ally. And this commitment was reaffirmed in 1908 by Bülow’s support for Austria’s abrupt annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. This in the eyes of many liberal imperialists in Berlin was to prove a tragic mistake. Richard von Kühlmann, a leading advocate of détente with Britain, who would serve as Germany’s foreign secretary during World War I and was driven out of office in the summer of 1918 as a result of clashes with Ludendorff and Hindenburg, would describe Berlin’s dependence on Vienna as the true tragedy of German power. From the vantage point of a liberal view of history, the true logic of World War I was a struggle over the inevitable dismantling of the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires. For a German liberal such as Kuehlmann for Berlin to have tied itself to the Habsburg Empire, a structure condemned by the nationality principle to historical oblivion, was a disaster. A true realism involved not sentimentality or blank cynicism but an understanding of history’s inner logic. A new Bismarck would, Kühlmann believed, have joined Britain in a partnership to oversee the dismantling of both Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, whose crisis was instead to result in the self-destruction of European power.

Instead, 1914 manifested an utter confusion of hierarchies. And in a historical moment characterized by extreme reflexivity it is hardly surprising that all these theories were anticipated and incorporated such that all sides derived justifications for their actions. Both the rally by German social democracy to national defense and Lenin’s defeatism were justified in terms of hierarchical notions of historical development. For both the pivot of the argument was Tsarist Russia.

At the time of the 1848 revolution and after both Marx and Engels had preached the need for a revolutionary war against reactionary Russia. Since the 1912 election the SPD had emerged as the largest party in the Reichstag. As a socialist party it was committed to a Marxist interpretation of history and thus to the cause both of progress and internationalism. It was also, of course, a mass party enrolling millions of voters many of whom were proud German patriots, who saw in August 1914 a patriotic struggle and an occasion for national cross class unity. Famously the party like virtually all its other European counterparts voted for war credits. But despite the abuse hurled at them by more radical internationalists, for the SPD as for other European socialists, it was not naked patriotism that triumphed in 1914. What overrode their internationalism was their determination to defend a vision of progress cast within a national developmental frame. World War I was a progressive war for German social democracy in that it was through the war that domestic reform would be won. It was not by coincidence that it was during the war that the Weimar coalition between the SPD, progressive liberals and Christian Democrats was forged. It was that coalition that delivered the progressive constitution of the Weimar Republic. This was a democratic expression of the spirit of August 1914. It was the first incarnation of Volksgemeinschaft in democratic form. It was defensive in inspiration. An Anglophile like Bernstein deeply regretted the war in the West, but there was no question where he stood in August 1914. The cause of progress in Germany would not be helped by surrendering to the rapacious demands of the worst elements of Anglo-French imperialism. If the Tsar’s brutal hordes were to march through Berlin, the setback to progress would be world historic. But it was not merely a revisionist like Bernstein who took this view. Hugo Haase, the later founder of the USPD, justified his support for the war on 4 August in strictly anti-Russian terms: ‘The victory of Russian despotism, sullied with the blood of the best of its own people, would jeopardise much, if not everything, for our people and their future freedom. It is our duty to repel this danger and to safeguard the culture and independence of our country’.

Lenin himself employed a similar logic in developing his position on the war in 1914. In his September 1914 manifesto Lenin declared the defeat of Tsarism the ‘lesser evil”. Nor did Lenin shrink from making comparisons. In his letter to Shlyapnikov of 17 October, he wrote: “for us Russians, from the point of view of the interests of the working masses and the working class of Russia, there cannot be the smallest doubt, absolutely any doubt, that the lesser evil would be now, at once the defeat of tsarism in this war. For tsarism is a hundred times worse than Kaiserism.” Early in 1915 this line was reiterated in a resolution proposed to the conference of the exiled Bolshevik party that echoed Marx and Engels in 1848. All revolutionaries should work for the overthrow of their governments and none should shrink from the prospect of national defeat in war. But for Russian revolutionaries this was essential, because a “victory for Russia will bring in its train a strengthening of reaction, both throughout the world and within the country, and will be accompanied by the complete enslavement of the peoples living in areas already seized. In view of this, we consider the defeat of Russia the lesser evil in all conditions.”

Lenin, of course, was at pains to distance himself from the logic of national defense that would seem to follow from his comment for German social democracy. Instead, he called on revolutionaries to raise the stakes by launching a civil war. But, given the difficulties that Lenin had in formulating his own position, it is hardly surprising that the SPD chose a more obvious path. A German defeat at the hands of the Russian army would be a disaster. So long as the main aim was defense against the Tsarist menace they could be won for a defensive war. And this was well understood on the part of the Reich’s leadership who by 1914 were convinced that they needed to bring the opposition party onside. To secure the solidity of the German home front it was absolutely crucial from the point of view of Bethmann Hollweg’s grand strategy during the July crisis that Russia must be seen to be the aggressor. Throughout the desperate final days of July Berlin waited for the Tsar’s order to mobilise before unleashing the Schlieffen Plan. As Bethmann Hollweg well understood, whatever Germany’s own entanglements with Vienna, only if the expectations of a modernist vision of history were confirmed by a first move on the Tsar’s part could the Kaiser’s regime count on the support of the Social Democrats, who were in their vast majority devoted adherents of a stage view of history that placed Russia far behind Imperial Germany. It was Russia’s mobilisation on 30 July 1914 that served as a crucial justification for a defensive war, which by 1915 had become a war to liberate the oppressed nationalities from the Tsarist knout, first the Baltics and Poland then Ukraine and the Caucasus.

The logic of the imperialist age was at work here in multiple layers of determination. In the threat of being locked in life and death competition with Russia. In the significance of Russia’s railway development and the scale of its military mobilization. But also in assumptions about the aggression that such a regime would surely manifest and what the appropriate reaction of a progressive Empire like Germany should be.

Most fundamentally what were at stake were conceptions of history. This subtle point is explicated by Schroeder himself in the telling image he chooses to illustrate the difference between the classical game of great power politics and the age of imperialism.

The classical game of great power politics, Schroeder suggests, was like a poker game played by highly armed powers but with a sense of common commitment to upholding the game. It was thus eventful, but repetitive, highly structured and to a degree timeless. There was no closure. Win or lose, the players remained the same. Imperialism, by contrast, was more like the brutal and notoriously ill-defined game of Monopoly. Under the new dispensation the players’ sole aim was accumulation up to and including the out-right elimination of the competition through bankruptcy. As Eric Hobsbawm also pointed out, one of the novelties of the situation before 1914 was that great power status and economic standing had come to be identified and the terrifying aspect of capital accumulation was that it had not natural limit.

The difference with regard to temporal dynamics is striking. Unlike an endlessly repeated poker round, as the game of Monopoly progresses, the piling up of resources and the elimination of players marks out an irreversible, ‘historical’ trajectory. Unselfconsciously Schroeder thus introduces into the discussion one of the most fundamental ideas suggested by Hannah Arendt in the critique of imperialism and capitalist modernity that she first developed in The Origins of Totalitarianism. What she described was precisely the colonisation of the world of politics by the limitless voracious appetites of capital accumulation. And for her too this brought with it a new and fetishistic relationship to history.

If global capitalist development was tied up in a very deep way with dynamic that drove the powers to war in 1914, so too was its guiding ideology of liberalism. Liberalism is not imperialism’s other, as by 1918 would be suggested by Woodrow Wilson’s reworked version of liberal ideology. Nor, on the other hand, is it reducible to, or identical with imperialism, as some critics would allege. They undeniably existed within the same space and in the early 20th century constituted each other.

Liberalism could justify violent escalation - “the war to end all wars” etc. But that violent dialectic was only one possibility. The moment also gave rise to a new crop of theories of world order order and “ultra-imperialism” as advanced, for instance by Karl Kautsky and J.A. Hobson.

The problem of finding a new global order in the early twentieth century, the idea that came to such prominence in the wake of World War I, is not best understood in terms of “idealism” or the soft tissue of a disempowered international civil society. As I argued in Deluge, the project of world order, is best understood, as a power-political project.

And this is where the question of hegemony enters in.

With the plausibility of empire as a means of global ordering having reached its limit, hegemony is a convenient term for a global ordering of power amongst the powerful. The concept is indispensable. But it is also a snare.

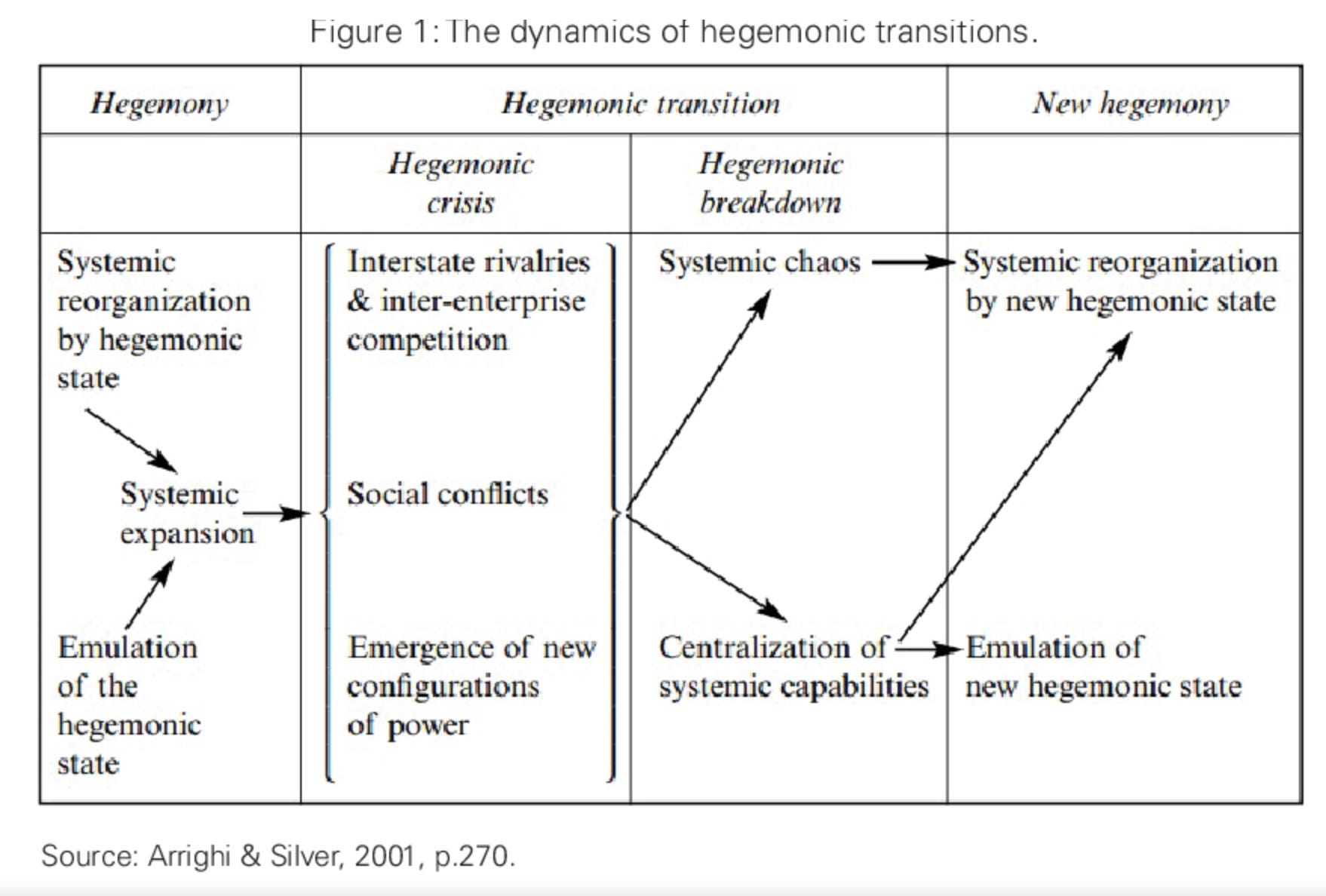

In the wake of the interwar crisis, analysts, taking inspiration from cyclical models of the development of capitalism, posited that hegemony was, if not a universal tendency, then certainly a recurring imperative of modern capitalism. To function well, the system needs a hegemon. Always!

This was the thesis both of Kindleberger and Arrighi.

The interwar crisis was the latest to result from a phase of hegemonic transition. In this case the baton dropped as it passed from the British Empire to the US.

There can be little doubt that a baton dropped. But what was at stake was not some ancient scepter of hegemonic power passed down from the Genoese to the Dutch, from them to the British and from there to the United States - the phrase is translatio imperii.

That is of course an attractive idea for empire-builders, but its significance is as a piece of ideology rather than as an explanation. British power in the 19th century constituted the global condition, in Geyer and Bright’s terms, but it had precious little to do with hegemony as the US exercised it after 1945 - as instantiated in organizations like NATO and the European Community. Those were tools of order suited for an age of extremes. The problem of order is defined by the forces in play. The transhistoric notion of a hegemonic imperative fails to do justice to the explosive force of accumulation and state-formation unleashed from the middle of the nineteenth century i.e. the age of imperialism. To corral those forces, hegemony of a far more robust and intrusive kind was required.

The British Empire did attempt to raise its game to match the challenges of the era. I take this to be the point of John Darwin’s indispensable Empire Project. But that radical new British ambition, to hold the global ring not at a distance, but through direct engagement of all the key players, suffered shipwreck in 1922 at Genoa. That was the moment, especially in comparison with the remarkable deal brokered at the naval conference in Washington, that America’s indispensability - in this conjuncture, at this moment - became undeniable. More on this to follow.