A promessa (de 1997) e a atual realidade: a natureza autoritária, senão totalitária, não apenas do PCC, que controla a China desde 1949, mas das características básicas do sistema político chinês desde sempre, fo Império do Meio, não permitem o estabelecimento de um regime de liberdades individuais, tal como ocorreu nas sociedades da Europa ocidental herdeiras do mundo greco-romano e cristão da Antiguidade e da Idade Média. Mas essa evolução ocorrerá em algum momento do futuro: o espírito de Hong Kong prevalecerá no futuro previsível (e já ocorreu, nas revoltas estudantis de 1919 e de 1989).

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

Hong Kong’s Freedoms: What China Promised and How It’s Cracking Down

- Before the British government handed over Hong Kong in 1997, China agreed to allow the region considerable political autonomy for fifty years under a framework known as “one country, two systems.”

- In recent years, Beijing has cracked down on Hong Kong’s freedoms, stoking mass protests in the city and drawing international criticism.

- Beijing imposed a national security law in 2020 that gave it broad new powers to punish critics and silence dissenters and could fundamentally alter life for Hong Kongers.

Introduction

China pledged to preserve much of what makes Hong Kong unique when the former British colony was handed over more than two decades ago. Beijing said it would give Hong Kong fifty years to keep its capitalist system and enjoy many freedoms not found in mainland Chinese cities.

But it seems that these promises are fading. In recent years, Beijing has taken what critics say are brazen steps to encroach on Hong Kong’s political system and crack down on dissent. These moves sparked massive protests in Hong Kong and have drawn international condemnation. In 2020, Beijing passed a controversial national security law and arrested dozens of pro-democracy activists and lawmakers, dimming hopes that Hong Kong will ever become a full-fledged democracy.

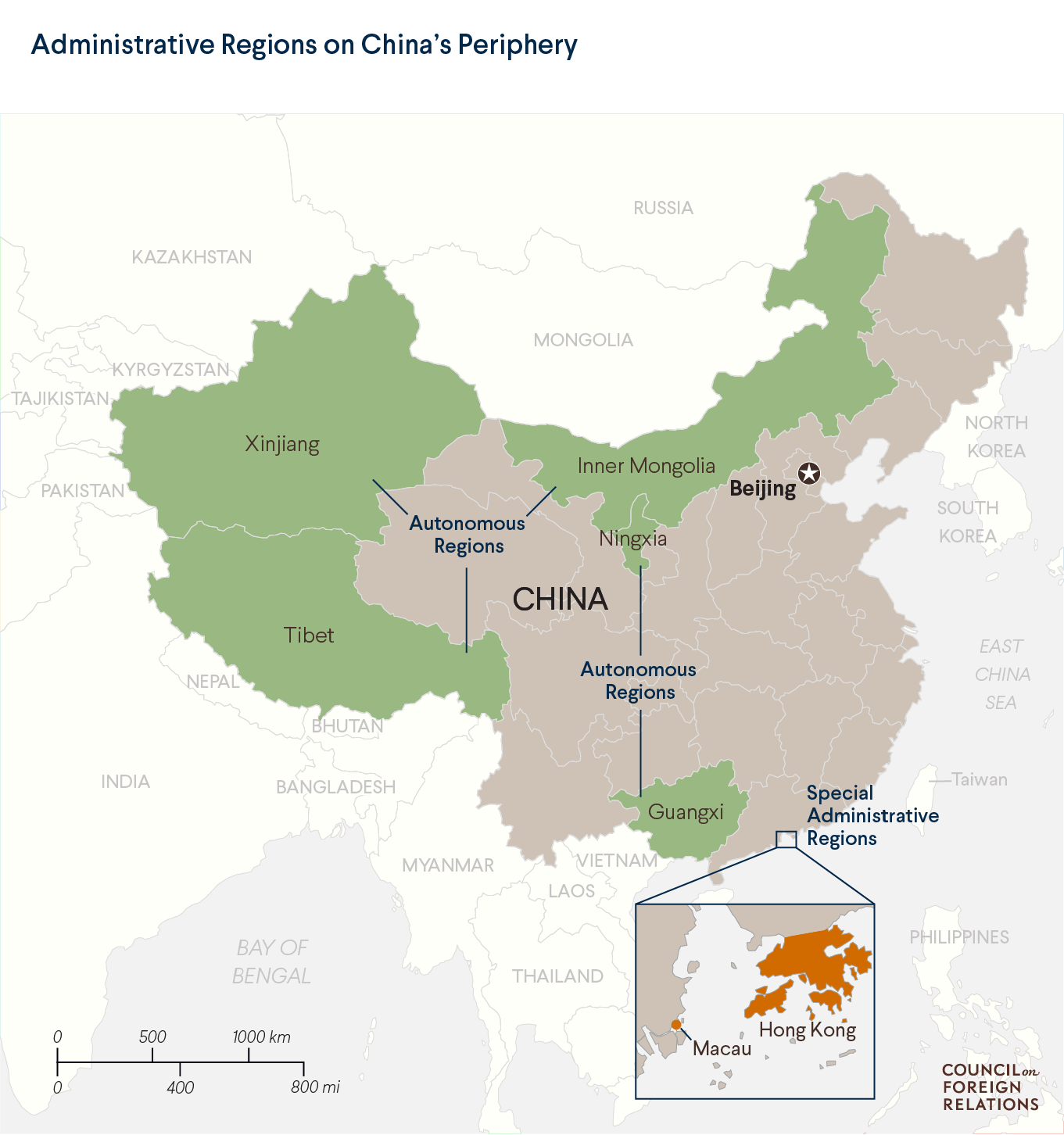

Is Hong Kong part of China?

Hong Kong is a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China that has been largely free to manage its own affairs based on “one country, two systems,” a national unification policy developed by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s. The concept was intended to help integrate Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau with sovereign China while preserving their unique political and economic systems. After more than a century and a half of colonial rule, the British government returned Hong Kong in 1997. (Qing Dynasty leaders ceded Hong Kong Island to the British Crown in 1842 after China’s defeat in the First Opium War.) Portugal returned Macau in 1999, and Taiwan remains independent.

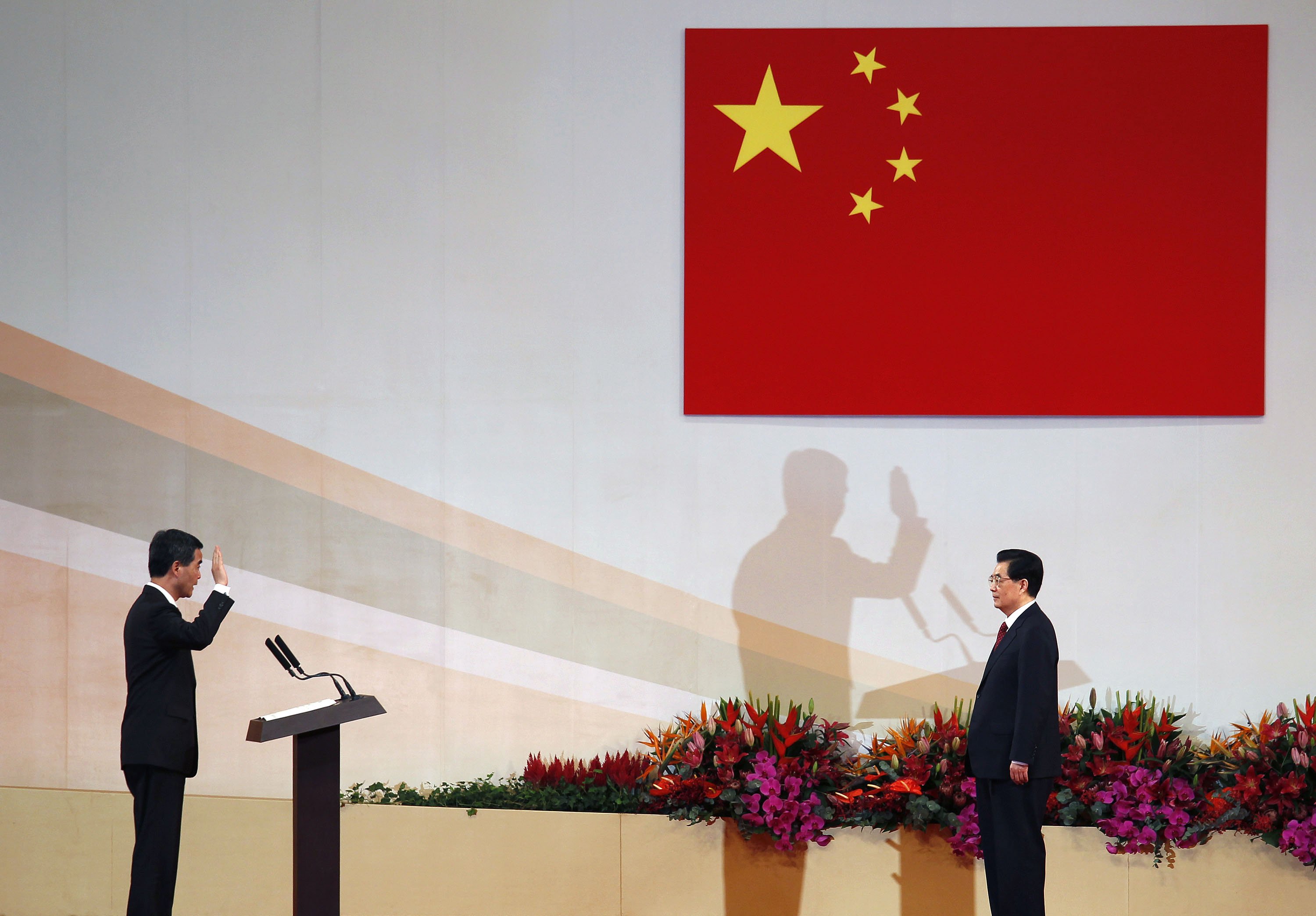

The Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 dictated the terms under which Hong Kong was returned to China. The declaration and Hong Kong’s Basic Law, the city’s constitutional document, enshrine the city’s “capitalist system and way of life” and grant it “a high degree of autonomy,” including executive, legislative, and independent judicial powers for fifty years (until 2047).

Chinese Communist Party officials do not preside over Hong Kong as they do over mainland provinces and municipalities, but Beijing still exerts considerable influence through loyalists who dominate the region’s political sphere. Beijing also maintains the authority to interpret Hong Kong’s Basic Law, a power that it had rarely used until recently. All changes to political processes have to be approved by the Hong Kong government and China’s top legislative body, the National People’s Congress, or its Standing Committee.

Hong Kong is allowed to forge external relations in certain areas—including trade, communications, tourism, and culture—but Beijing maintains control over the region’s diplomacy and defense. Under the Basic Law, Hong Kongers are guaranteed freedoms of the press, expression, assembly, and religion, as well as protections under international law. But in practice, Beijing has curtailed some of these rights.

Is Hong Kong a democracy?

Although Hong Kong has certain freedoms, it is not a full democracy [PDF] by international standards. China is a one-party state and is reluctant to allow Hong Kong to hold free and fair elections. Experts say that ambiguity in the Basic Law heightens this fundamental tension. The document states that the “ultimate aim” is to have Hong Kong’s leader elected by a popular vote, but it does not give a deadline for this to occur.

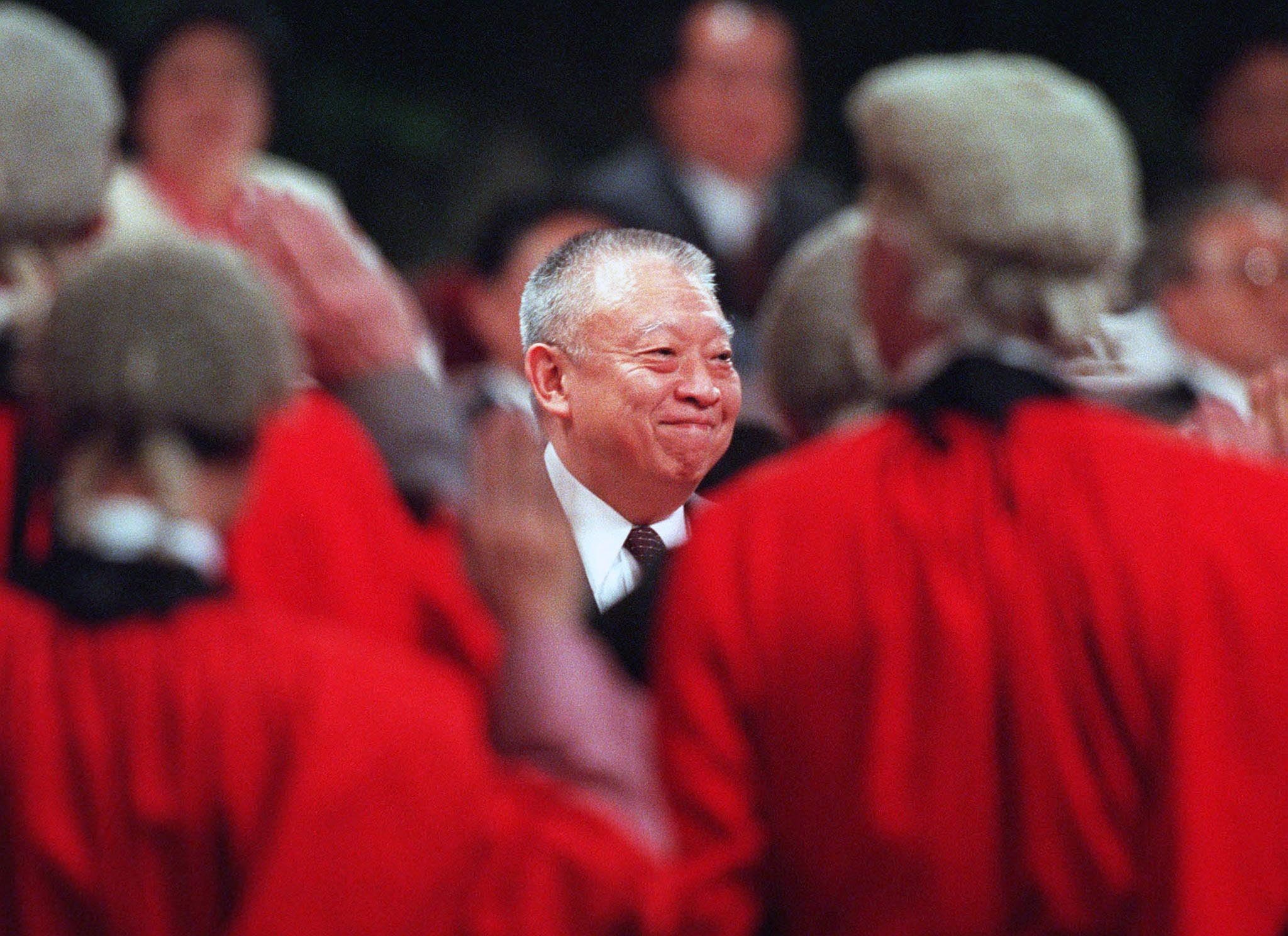

Since the handover, there have been no free votes by universal suffrage for the chief executive, who is the head of the Hong Kong government. Instead, an election committee composed of representatives from Hong Kong’s main professional sectors [PDF] and business elite has selected them. During the most recent election, in 2017, only candidates vetted by a nominating committee chosen by Beijing were allowed to run. Carrie Lam, viewed as an establishment candidate, won and became Hong Kong’s first woman chief executive.

Thirty-five members of Hong Kong’s legislature, the Legislative Council, are elected by direct voting, while the other thirty-five members are chosen by groups representing different industries and professions. Hong Kong residents also get to vote for members of their local district councils, which handle day-to-day community concerns.

Unlike China, Hong Kong has numerous political parties. They have traditionally split between two factions: pan-democrats, who call for incremental democratic reforms, and pro-establishment groups, who are by and large pro-business supporters of Beijing. The latter have typically been more dominant in Hong Kong politics, but pro-democracy groups have increasingly garnered more support from voters.

Traditionally, only a small minority of Hong Kongers have favored outright independence. However, in recent years, student protesters demanding a more demoractic system have formed political groups, including more radical, anti-Beijing parties, such as Youngspiration, and Hong Kong Indigenous, and Demosisto. These parties tapped into the phenomenon in which more and more people see themselves as Hong Kongers or as Hong Kongers in China as opposed to identifying as Chinese nationals. Several of these groups disbanded in 2020, however, as Beijing cracked down on political opposition.

How has Beijing eroded Hong Kong’s freedoms?

Beijing has been chipping away at Hong Kong’s freedoms since the handover, experts say. Over the years, its attempts to impose more control over the city have sparked mass protests, which have in turn led the Chinese government to crack down further.

“In the fifteen years after the handover, there was a series of official initiatives aimed at enhancing Beijing’s control in ways that would undermine both the autonomy and the rule of law,” Michael C. Davis writes in his book Making Hong Kong China.

For instance, in 2003, the Hong Kong government proposed national security legislation that would have prohibited treason, secession, sedition, and subversion against the Chinese government. In 2012, it tried to amend Hong Kong schools’ curricula to foster Chinese national identity, which many residents saw as Chinese propaganda. And in 2014, Beijing proposed a framework for universal suffrage, allowing Hong Kongers to vote for the city’s chief executive but only from a Beijing-approved short list of candidates. Protesters organized massive rallies, known as the Umbrella Movement, to call for true democracy.

In the years following the 2014 protests, Beijing and the Hong Kong government stepped up efforts to rein in dissent, including by prosecuting protest leaders, expelling several new legislators, and increasing media censorship.

Hong Kong Since the Handover

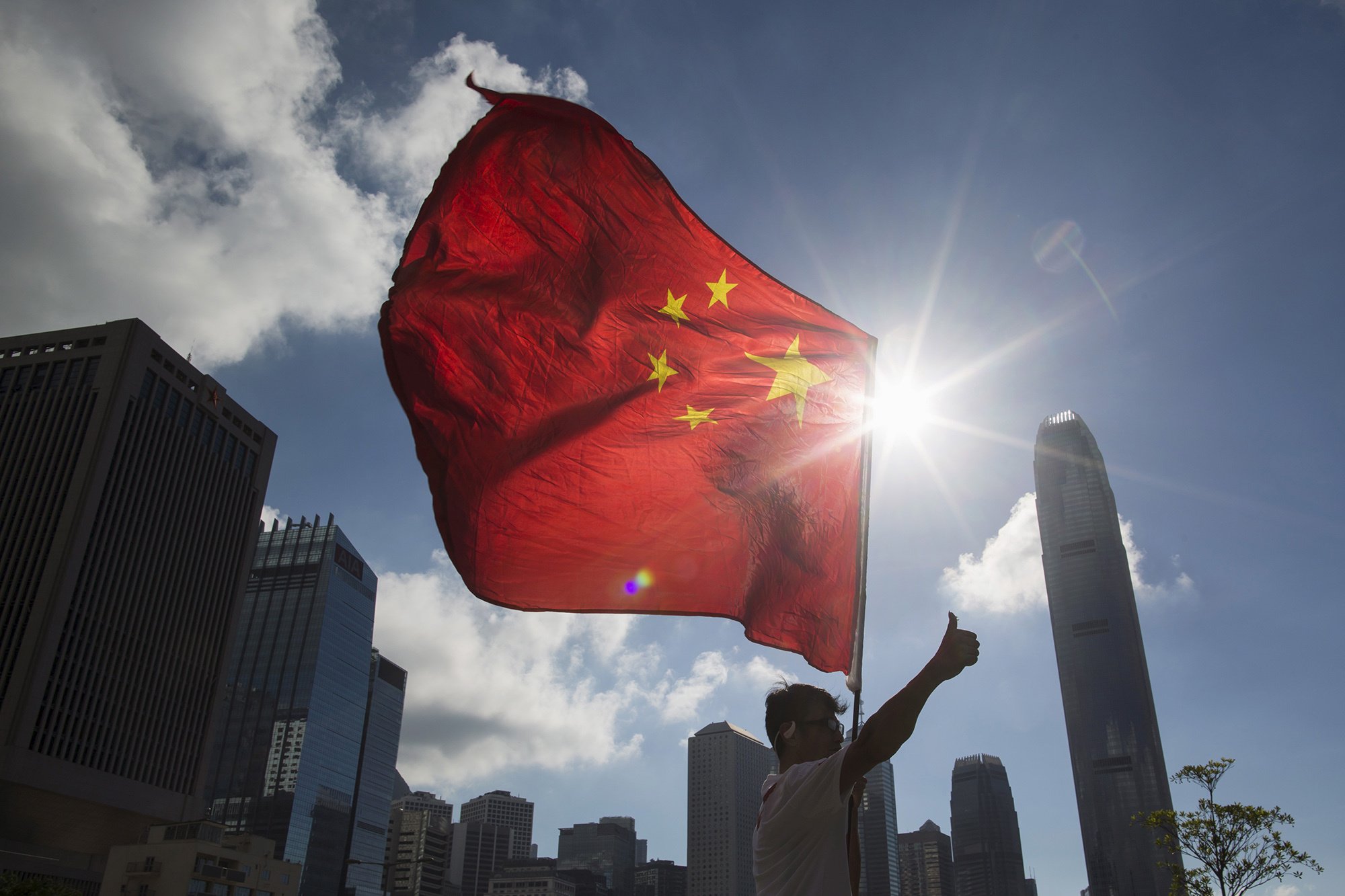

In the summer of 2019, Hong Kong saw its largest protests ever. For months, people demonstrated against a Beijing-endorsed legislative proposal that would have allowed extraditions to mainland China. Many protesters believed Beijing had eroded Hong Kong’s freedoms to such an extent that they thought, “either we stop it now, or it’s just basically going to be hell,” says Victoria Tin-bor Hui, a political science professor at the University of Notre Dame. Reports of police brutality, including the excessive use of tear gas and rubber bullets, exacerbated tensions. Chief Executive Lam withdrew the bill in September, but the protests, which garnered international attention, continued until the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020.

What is the national security law Beijing imposed on Hong Kong?

Beijing took its most assertive action yet on June 30, 2020, when it bypassed the Hong Kong legislature and imposed a new national security law on the city. The legislation effectively criminalizes any dissent, and adopts extremely broad definitions for crimes such as terrorism, subversion, secession, and collusion with foreign powers. It also allows Beijing to establish a security force in Hong Kong and influence the selection of judges who will hear national security cases. Pro-democracy activists and lawmakers decried the move and expressed fears that it could be “the end of Hong Kong.” Meanwhile, Chinese officials and pro-Beijing lawmakers said it was necessary to restore stability following the massive protests.

Authorities have used the law to try to eliminate all forms of political opposition. They disqualified pro-democracy candidates from running in the 2020 legislative elections, which were ultimately postponed, and removed elected lawmakers for publicly opposing China’s control over Hong Kong. In addition, police have arrested dozens of Hong Kong’s most prominent pro-democracy activists and former lawmakers, and the government has started to prosecute them. These moves have silenced many Hong Kong residents who had fought for democracy and prompted others to flee the city. The Hong Kong government’s efforts to transform the public education system by introducing so-called patriotic programs have also troubled many parents and students.

What has been the international response to Beijing’s actions?

Several countries have condemned Beijing’s moves and taken retaliatory measures. The administration of former U.S. President Donald J. Trump imposed sanctions on Chinese officials it alleged were undermining Hong Kong’s autonomy, including Lam; restricted exports of defense equipment to Hong Kong; and started revoking its special trade status. The United States also joined a handful of countries, such as Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, that suspended their extradition treaties with Hong Kong because of the national security law. U.S. President Joe Biden has indicated that his administration will continue to press for Hong Kong’s freedoms. In his first phone call with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, Biden voiced concerns about Beijing’s crackdown.

The United Kingdom, which also ended its extradition agreement with the region, said it would allow three million Hong Kong residents to settle in the country and apply for citizenship. Canada announced measures to make it easier for Hong Kong youth to study and work in the country, creating pathways for permanent residency. The European Union, which expressed “grave concern” about the national security law, limited exports of equipment that China could use for repression and vowed to ease visa and asylum policies for Hong Kong residents.

However, the opposition has not been unanimous. Fifty-three countries—most of which are participating in China’s Belt and Road infrastructure project—signed a statementread before the UN Human Rights Council in July 2020 supporting Beijing’s national security law, while only twenty-seven countries signed an opposing statement criticizing it.

What does Beijing’s crackdown mean for Hong Kong’s financial status?

It is too soon to tell whether Beijing’s actions will jeopardize Hong Kong’s role as a global financial hub. Relatively low taxes, a highly developed financial system, light regulation, and other capitalist features have made Hong Kong one of the world’s most attractive markets and set it apart from mainland financial hubs such as Shanghai and Shenzhen. Multinational firms and banks—many of which maintain regional headquarters in Hong Kong—have historically used the city as a gateway to do business in the mainland, owing in part to its proximity to the world’s second-largest economy and its legal system based on British common law.

However, executives of some companies with large footprints in Hong Kong have recently voiced concerns about the national security law, criticizing the broad powers given to mainland authorities. Some firms are reportedly considering leaving the city or are boosting hiring in other Asian financial capitals, such as Singapore and Tokyo. A majority of U.S. companies surveyed in July 2020 said they were concerned about the legislation. In particular, social media companies, including Facebook and Google, have expressed concerns about part of the law that requires them to surrender requested user data to the Hong Kong government. TikTok, an app owned by mainland-based company ByteDance, suspended operations in Hong Kong.

“Beijing’s ideal scenario is to keep Hong Kong as a financial center without all the freedom. But it seems that you really cannot maintain Hong Kong’s international financial standing while stifling its freedom,” Hui says.

Other experts believe that Hong Kong will maintain its commercial status despite its democratic decline. In recent years, Beijing has moved to connect Hong Kong more to the mainland, creating the Greater Bay Area project, an ambitious plan to integrate Hong Kong and cities in neighboring Guangdong Province into a more cohesive economic region. Many firms and investors are betting that this increased connectivity will boost the amount of wealth flowing from the mainland into Hong Kong in the future.

“This dramatic transformation will not be the end of Hong Kong as a global financial hub, as it has already begun to boost economic integration with mainland China. But it is surely the death of the democratic hopes of most of its 7.5 million people,” CFR’s Jerome A. Cohen writes.

Recommended Resources

On The President’s Inbox podcast, Victoria Tin-bor Hui explains the national security law imposed on Hong Kong.

In Foreign Affairs, Michael C. Davis argues that Hong Kong is now part of mainland China.

The Congressional Research Service outlines the national security law for Hong Kong [PDF], the composition of Hong Kong’s legislative body [PDF], and the status of U.S.-Hong Kong relations [PDF].

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation tells the story of the massive protests in 2019.

The Financial Times lays out Xi Jinping’s grand plan for the Greater Bay Area.