|

| HELENE ROGERS / ALAMY |

| A modern statue of Ibn Khaldun stands in the center of his native city. |

Written by Caroline Stone

Abu Zayd ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn Khaldun al-Hadhrami, 14th-century Arab historiographer and historian, was a brilliant scholar and thinker now viewed as a founder of modern historiography, sociology and economics. Living in one of humankind’s most turbulent centuries, he observed at first hand—or even participated in—such decisive events as the birth of new states, the death throes of al-Andalus and the advance of the Christian reconquest, the Hundred Years’ War, the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, the decline of Byzantium and the great epidemic of the Black Death. Albert Hourani described Ibn Khaldun’s world as “full of reminders of the fragility of human effort”; out of his experiences, Arnold Toynbee wrote, “He conceived and created a philosophy of history that was undoubtedly the greatest work ever created by a man of intelligence….” So groundbreaking were his ideas, and so far ahead of his time, that a major exhibition now takes his writings as a lens through which to view not only his own time but the relations between Europe and the Arab world in our own time as well. —The Editors

His LifeIbn Khaldun’s ancestors were from the Hadhramawt, now southeastern Yemen, and he relates that, in the eighth century, one Khaldun ibn ‘Uthman was with the Yemeni divisions that helped the Muslims colonize the Iberian Peninsula. Khaldun ibn ‘Uthman settled first at Carmona and then in Seville, where several of the family had distinguished careers as scholars and officials.

During the Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, the family emigrated to North Africa, probably about 1248, eventually settling in Tunis. There Ibn Khaldun was born on May 7, 1332. He received an excellent classical education, but when he was 17, the plague, or Black Death, reached the city. His parents and several of his teachers died. The terrible epidemic that struck the Middle East, North Africa and Europe in 1347–1348, killing at least one-third of the population, had a traumatic effect on the survivors. Its impact showed in every aspect of life: art, literature, social structures and intellectual life. It was clearly one of the experi- ences that shaped Ibn Khaldun’s perception of the world.

Tunis was not only ravaged by the Black Death, but had also been reduced to political chaos by its occupation between 1340 and 1350 by the Marinids, the Berber dynasty that ruled Morocco. At 20, Ibn Khaldun set out for Fez, the Marinid capital, the liveliest court in North Africa. On the strength of his education, he was offered a secretarial position, but left before long. Although some historians regard his departure as disloyal, it is more likely he was fleeing the general political disintegration.

This was to be a pattern in Ibn Khaldun’s life. He was constantly tempted to become involved in murky political intrigues which, combined with the extreme instability of most of the ruling dynasties, meant that he had little choice but frequent changes of master. These experiences, like those of the Black Death, were instrumental in shaping his outlook.

After a number of moves, he found himself back in Fez, where the previous Marinid ruler had been supplanted by his son, Abu ‘Inan, to whom Ibn Khaldun offered his services. Soon, however, he was once again caught up in political turmoil, and after many changes of fortune, including two years in prison, he decided to withdraw to Granada in 1362. The roots of this decision went back several years.

|

| GILLES LE MUSIT / ROYAL LIBRARY OF BELGIUM / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| The Great Plague, or Black Death, swept from Central Asia to Europe, killing an estimated one-third of the population wherever it spread. It reached Tunis in 1348 when Ibn Khaldun was 17; its victims included his parents and several of his teachers. These losses, together with the ensuing social and economic chaos, deeply affected him. |

In 1359, the ruler of Granada, Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar, had been forced to flee to Fez together with his vizier, Ibn al-Khatib, one of the most famous scholars of the age. There they had met Ibn Khaldun. A warm friendship had developed, so that when, in turn, Ibn Khaldun had to escape from similarly dangerous politics, he was received in Granada with honors. Two years later, in 1364, Ibn Khaldun was sent by Ibn al-Ahmar to Seville on a peace mission to King Pedro I of Castile, known as “Pedro the Cruel.” In his Autobiography (Ta‘rif), Ibn Khaldun describes how Pedro offered to return his family estates and properties to him, and how he refused the offer. This contact with a Christian power was another watershed experience. He reflected not only on his own family’s past, but also on the changing fate of kingdoms—and above all on the historical and theological implications of the reassertion of Christian power in Iberia after more than five centuries of Muslim hegemony.

THE BLACK DEATH

“Civilization both in the East and the West was visited by a destructive plague which devastated nations and caused populations to vanish. It swallowed up many of the good things of civilization and wiped them out. It overtook the dynasties at the time of their senility, when they had reached the limit of their duration. It lessened their power and curtailed their influence. It weakened their authority. Their situation approached the point of annihilation and dissolution. Civilization decreased with the decrease of mankind. Cities and buildings were laid waste, roads and way-signs were obliterated, settlements and mansions became empty, dynasties and tribes grew weak. The entire inhabited world changed. The East, it seems, was similarly visited, though in accordance with and in proportion to [the East’s more affluent] civilization. It was as if the voice of existence in the world had called out for oblivion and restriction, and the world responded to its call.”

—tr. Rosenthal

|

Later, personal clashes with Ibn al-Khatib, probably fueled by a mixture of jealousy and court intrigue, drove Ibn Khaldun back to the turmoils of North Africa. He had repeatedly expressed the wish to devote his life to scholarship, but the political world clearly fascinated him. Over and over he succumbed to its temptations; in any case, so well-known a figure was unlikely to be left in peace to study.

In spite of their differences, Ibn Khaldun continued to correspond with Ibn al-Khatib, and several of these letters are cited in his Autobiography. He also tried to save his friend when, largely as a result of court intrigue, Ibn al-Khatib was brought to trial, accused of heresy for contradicting the ‘ulama, the religious authorities, by insisting that the plague was a communicable disease. His situation can be compared with that of Galileo nearly three centuries later, but with a less happy outcome: Ibn al-Khatib was strangled in prison at Fez in the late spring of 1375.

Ibn Khaldun was much affected by his friend’s death, not only personally, but also because of the political and religious implications of such an execution. Not long afterward, he withdrew to the Castle of Ibn Salamah, not far from Oran in Algeria. There, for the first time, he could really dedicate himself to study and reflect on what he had learned from books, as well as on his often bitter experience of the violent and turbulent world of his day.

The fruit of this period of calm was the Muqaddimah or Introduction to his Kitab al-‘Ibar (The Book of Admonitions or Book of Precepts, also often referred to as the Universal History.) Although these are really one work, they are often considered separately, for the Muqaddimah contains Ibn Khaldun’s most original and controversial perceptions, while the Kitab al-‘Ibar is a conventional narrative history. Ibn Khaldun continued to rewrite and revise his great work in the light of new information or experience for the rest of his life.

He spent the years from 1375 to 1379 at the Castle of Ibn Salamah, but at last felt the need for intellectual companionship—and for proper libraries in which to continue his research. At the age of 47, Ibn Khaldun returned again to Tunis, where “my ancestors lived and where there still exist their houses, their remains and their tombs.” He planned to travel no more and to settle down as a teacher and scholar, eschewing all political involvement.

|

| ROYAL MUSEUM OF ART AND HISTORY, BRUSSELS / EL LEGADO ANDALUSI |

| This helmet bears the name of the Mamluk sultan Ibn Qala’un, who ruled from Cairo a century before Barquq, the sultan who appointed and dismissed Ibn Khaldun as chief justice on several occasions. |

That was not so easy. Some considered his rationalist teachings subversive, and the imam of al-Zaytunah Mosque in Tunis, with whom he had been on terms of rivalry since his student days, became jealous. To make matters yet more difficult, the sultan insisted that Ibn Khaldun remain in Tunis and complete his book there, since a ruler’s status was greatly enhanced by attracting learned men to his court.

The situation finally became so tense and so difficult that in 1382 Ibn Khaldun asked permission to leave to perform the hajj, the pilgrimage to Makkah—the one reason for withdrawal that could never be denied in the Islamic world. In October he set out for Egypt. He was immensely impressed by Cairo, which exceeded all his expectations. There, the Mamluk sultan Barquq received him with enthusiasm and gave him the important position of qadi, or justice, of the Maliki school of Islamic law.

This, however, proved to be no sinecure. In his Autobiography, Ibn Khaldun describes how his efforts to combat corruption and ignorance, together with the jealousy aroused by the appointment of a foreigner to a top job, meant that once again he found himself in a hornets’ nest. It was something of a relief when the sultan dismissed him in favor of the former qadi. In fact, before the end of his life, Ibn Khaldun was to be appointed and dismissed no fewer than six times.

Ibn Khaldun was married and had children; he had a sister who died young—her tombstone survives—and his brother Yahya ibn Khaldun was also a very distinguished historian. However, we know very little about his personal life: It was not the Muslim, and in particular not the Arab, custom to include personal details in one’s writings. We do know, however, that at about this time, Ibn Khaldun’s family and household, which was essentially being held hostage at Tunis for his return, were given permission to join him in Cairo. This was at the personal request of Barquq, whose letter is quoted in the Autobiography. But the boat carrying his family went down in a tempest off Alexandria, and no one survived.

|  |

| DICK DOUGHTY (2) | |

| In 1364, Ibn Khaldun journeyed to Seville, seat of the Christian monarch Pedro I, king of Castile, whose magnificent Real Alcázar (“Royal Palace”) was then close to completion. Left:Pedro’s name is inscribed on the façade of his palace above tilework by Muslim mudejar artisans: an inscription in stylized “mirrored Kufic,” which is reflected on either side of the centerline of this image. Right: the delicately carved arches of the Patio del Yeso (Patio of the Stuccoes). | |

Three years passed. Ibn Khaldun dedicated himself to teaching and then at last set out to perform the hajj in 1387 with the Egyptian caravan. Ibn Khaldun says little of his pilgrimage, but he mentions that at Yanbu‘ he received a letter from his old friend, Ibn Zamrak, many of whose poems are inscribed on interior walls of the Alhambra. Ibn Zamrak, then the confidential secretary of the ruler of Granada, asked among other things for books from Egypt. It is one more example of how Ibn Khaldun maintained his intellectual contacts all across the Arabic-speaking world.

THE CONTENTS OF THE MUQADDIMAH

—tr. Issawi

|

On his return to Cairo, Ibn Khaldun held various teaching posts, but from 1399 the cycle of political appointments and dismissals began again. The scholar had already witnessed at first hand the political upheavals caused by the various Berber dynasties in North Africa, as well as the success of the Christian powers in reducing the Muslim kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula. Now he was about to witness another example of the rise and fall of empires, this time with an epicenter farther to the east than he had ever traveled.

In 1400, Ibn Khaldun was compelled by Barquq’s successor, Sultan al-Nasir, to travel to Damascus, where he took part in the negotiations with the Central Asian conqueror Timur, the Turco-Mongol ruler known in the West as Tamerlane. The aim was to persuade Timur to spare Damascus. Ibn Khaldun describes his conversations with Timur in some of the most interesting pages of his Autobiography.

In the end, however, the Egyptian diplomatic delegation was unsuccessful. Timur did sack Damascus and from there went on to take Baghdad, with great loss of life. The following year, Timur defeated the Ottomans at Ankara, taking their Sultan Beyazit prisoner. These events are described by the Spanish traveler Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo, who went out to Samarkand in 1403 as ambassador to Timur.

Ibn Khaldun’s Autobiography continues for no more than a page or two after his return from Damascus, and he mentions only his appointments and dismissals. Although he never returned to Tunis, he continued to think of himself as a westerner, wearing until the last the dark burnous that is still the national dress of North Africa. He continued to revise and correct his great work until his death in Cairo on March 16, 1406—600 years ago this past spring.

|

| REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN / LOUVRE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| In 1400, at the age of 67 or 68, Ibn Khaldun was compelled by the Mamluk sultan al-Nasir to travel to Damascus in an effort to convince the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur to spare the city. But the talks failed, and Damascus was mercilessly attacked. |

THE NEW SCIENCE

“This science then, like all other sciences, whether based on authority or on reasoning, appears to be independent and has its own subject, viz. human society, and its own problems, viz. the social phenomena and the transformations that succeed each other in the nature of society…. It seems to be a new science which has sprung up spontaneously, for I do not recollect having read anything about it by any previous writers. This may be because they did not grasp its importance, which I doubt, or it may be that they studied the subject exhaustively, but that their works were not transmitted to us. For the sciences are numerous, and the thinkers belonging to the different nations are many, and what has perished of the ancient sciences exceeds by far what has reached us.”

—tr. Issawi

|

His Work

Ibn Khaldun’s most important work was Kitab al-‘Ibar, and of that the most significant section was the Muqaddimah. Such “introductions” were a recognized literary form at the time, and it is thus not surprising that the Muqaddimah is both long—three volumes in the standard translation—and the repository of its author’s most original thoughts. Kitab al-‘Ibar, which follows, is much more conventional in both content and organization, although it is one of the most important surviving sources for the history of medieval North Africa, the Berbers and, to a lesser extent, Muslim Spain.

In the early 19th century, western scholars, already admirers of such Muslim thinkers as the philosopher Ibn Rushd, whom they knew as Averroes, became aware of the Muqaddimah, probably through the Ottoman Turks. They were struck by its originality—all the more so because it was written at a time when political and religious authority were exerting increasing pressure against independent thought, resulting in a decline of original scholarship. In this context, Ibn Khaldun’s interest in a whole range of subjects that today would be classified as sociology and economic theory, and his wish to create a new discipline to accommodate them, came as a particular surprise to scholars in both the Arab world and the West.

Many of the subjects that Ibn Khaldun discusses are not, however, new preoccupations. They had also concerned both Greek thinkers and earlier Arab writers, such as al-Farabi and Mas‘udi, to whom Ibn Khaldun refers frequently. The question of how much access Ibn Khaldun had to Greek sources in translation is still being debated, and in particular whether he had read Plato’s Republic. But Ibn Khaldun’s originality lies not in the fact he was conscious of these problems, but in his awareness of the complexity of their interrelationships and the need to study social cause and effect in a rigorous way.

It is in this way that Ibn Khaldun took his place in a chain of intellectual development. Although his work was not followed up by succeeding generations, and indeed met with some disapproval and even censure, the great Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi perhaps chose his career as a result of his acquaintance with Ibn Khaldun, and he developed some of Ibn Khaldun’s ideas. It was, however, the Ottoman Turks who took the most interest in his theories concerning the rise and fall of empires, since many of the points he discusses appeared to apply to their own political situation.

In the Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun’s central theme is why nations rise to power and what causes their decline. He divides his argument into six sections or fields. (See box, page 33.) At the beginning, he considers both source material and methodology; he analyzes the problems of writing history and notes the fallacies which most frequently lead historians astray. His comments are still relevant today.

Another aspect of Ibn Khaldun’s originality is his stress on studying the realities of human society and attempting to draw conclusions based on observation, rather than trying to reconcile observation with preconceived ideas. It is interesting that at the time Ibn Khaldun was writing, the humanist movement was well under way in Europe, and it shared many of the same preoccupations as Ibn Khaldun, in particular the great importance of the interaction between people and their physical and social environment.

One of Ibn Khaldun’s basic subjects is still being debated, and it is of the greatest relevance in the increasingly multicultural societies of today: What is social solidarity, and how does a society achieve it and maintain it? He argues that no society can achieve anything—conquer an empire or even survive—unless there is internal consensus about its aims. He does not argue in favor of democracy in any recognizable form (which suggests he may not have had intimate knowledge of the Greek political theorists), and he assumes the need for strong leadership, but it is clear that, to him, a successful society as a whole must be in agreement as to its ultimate goals.

He points out that solidarity—he uses the word ‘asabiyah—is strongest in tribal societies because they are based on blood kinship and because, without solidarity, survival in a harsh environment is impossible. If this solidarity is joined to the other most powerful social bond, religion, then the combination tends to be irresistible.

Ibn Khaldun perceives history as a cycle in which rough, nomadic peoples, with high degrees of internal bonding and little material culture to lose, invade and take resources from sedentary and essentially urban civilizations. These urban civilizations have high levels of wealth and culture but are self-indulgent and lack both “martial spirit” and the concomitant social solidarity. This is because those qualities have become unnecessary for survival in an urban environment, and also because it is almost impossible for the large number of different groups that compose a multicultural city to attain the same level of solidarity as a tribe linked by blood, shared custom and survival experiences. Thus the nomads conquer the cities and go on to be seduced by the pleasures of civilization and in their turn lose their solidarity and come under attack by the next group of rough and vigorous outsiders—and the cycle begins again. Ibn Khaldun perceives history as a cycle in which rough, nomadic peoples, with high degrees of internal bonding and little material culture to lose, invade and take resources from sedentary and essentially urban civilizations. These urban civilizations have high levels of wealth and culture but are self-indulgent and lack both “martial spirit” and the concomitant social solidarity. This is because those qualities have become unnecessary for survival in an urban environment, and also because it is almost impossible for the large number of different groups that compose a multicultural city to attain the same level of solidarity as a tribe linked by blood, shared custom and survival experiences. Thus the nomads conquer the cities and go on to be seduced by the pleasures of civilization and in their turn lose their solidarity and come under attack by the next group of rough and vigorous outsiders—and the cycle begins again.

Ibn Khaldun’s reflections derive, of course, from his experiences in a radically unstable time. He had seen Arab civilization overrun in some parts of the world and seriously undermined in others: in North Africa by the Berbers, in Spain by the Franks and in the heartlands of the caliphate by Timur and his Turco-Mongol hordes. He was well aware that the Arab empire had been founded by Bedouin who were, in terms of material culture, much less sophisticated than the peoples of the lands they conquered, but whose ‘asabiyah was far more powerful and who were inspired by the new faith of Islam. He was deeply saddened to watch what he saw as a cycle of conquest, decay and reconquest repeated at the expense of his own civilization.

As Ibn Khaldun developed his themes through the Muqaddimah, he presented many other innovative theories relating to education, economics, taxation, the role of the city versus the country, the bureaucracy versus the military and what influences affect the development of both individuals and cultures. It is in these themes that we find echoes of al-Mas‘udi’s Kitab al-Tanbih wa al-Ishraf, where he considers the factors that shape a nation’s laws: the nature of authority and the relationship between spiritual and temporal powers, to name only two.

It is worth remembering that, besides having witnessed a particularly turbulent period of history, Ibn Khaldun also had much practical experience of politics on both national and international levels. Furthermore, his various terms of duty as a qadi in Cairo gave him, as he claimed, insight into the problems of battling corruption and ignorance in a cosmopolitan environment, mindful of the “moral decadence” he believed to be one of the great threats to civilization. His conclusions were, as he tells us in his Autobiography, based on practical knowledge and direct observation, as well as academic theory.

It would be hard for any book to live up to the standard set by the Muqaddimah, and indeed Kitab al-‘Ibar does not. Although it is an invaluable source for the history of the Muslim West, it is less remarkable in other fields, and Ibn Khaldun did not share al-Mas‘udi’s lively and unbiased interest in the non-Muslim world. Other blank spots are all the more surprising in that Ibn Khaldun was living in Cairo with access to excellent libraries and bookshops.

On the other hand, there were occasions when he made great efforts to establish facts accurately. It must have required courage to ask Timur himself to correct the passages in the ‘Ibar that referred to him! Timur was of great interest to Ibn Khaldun, who hoped the conqueror might be the one to provide the social solidarity needed for a renaissance of the Muslim and, especially, the Arab worlds—but it was a short- lived hope.

Ibn Khaldun wrote a number of other books on purely academic subjects, as well as early works which have vanished. His Autobiography, although lacking personal details, contains extremely interesting information about the world in which he lived and, of course, about his meetings with Pedro and Timur.

Ibn Khaldun’s strength was thus not as a historian in the traditional sense of a compiler of chronicles. He was the creator of a new discipline, ‘umran, or social science, which treated human civilization and social facts as an interconnected whole and would help to change the way history was perceived, as well as written.

|

The Exhibition

Ibn Khaldun: The Mediterranean in the 14th Century: The Rise and Fall of Empires

Ibn Khaldun: The Mediterranean in the 14th Century: The Rise and Fall of Empires

The exhibition marking the 600th anniversary of the death of Ibn Khaldun could not be held in a more evocative place than Seville’s Real Alcázar (Royal Palace). Not only is it a most beautiful backdrop, but it is a building that Ibn Khaldun himself knew. He walked through the same rooms where the exhibition is being held today, and he stood in the great Audience Chamber when he met Pedro I “The Cruel” on his peace mission from the sultan of Granada in 1364.

|  |

| EL LEGADO ANDALUSI (2) | |

| Left: This small statue, lent by the Correr Museum of Venice, represents Antonio Venier, Doge of the Venetian Republic from 1382 to 1400, in the century after Marco Polo. He was responsible for reviving Venice’s economy after the Black Death and negotiating with the Mamluks to make the city Egypt’s most important trading partner; at this period Ibn Khaldun was resident in Cairo. The statue is displayed in the Real Alcázar’s Hall of the Ambassadors, where Ibn Khaldun may have been received by Pedro I. Right: The exhibition was officially opened on May 19 by Queen Sofía and King Juan Carlos I (center left and right), who still use the Real Alcázar as their residence in Seville and for ceremonial occasions. Joining them was Amre Moussa, secretary general of the League of Arab States (left) and Mohamed El Fatah Naciri, head of the League’s mission in Madrid, as well as leaders from Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Qatar and Tunisia. | |

That is, of course, if the rooms were complete, for in 1364 the palace was partly under construction by the Christian king “in the Moorish manner,” decorated with Arabic calligraphy by Muslim craftsmen in the style called mudejar. For Ibn Khaldun it must have been a strange experience to revisit the city where his ancestors had held high office and to walk through older areas of the palace, such as the Patio del Yeso (Patio of the Stuccoes), which they would have known.

|

| CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN MUSEUM, LISBON / EL LEGADO ANDALUSI |

| A small bowl from Persia, made of painted and glazed ceramic, dates from the 14th century. |

Opened by King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía of Spain and attended by royalty and dignitaries from many countries, the commemorative exhibition is dedicated to the world of Ibn Khaldun, placing him in the context of his age and doing much to explain his particular preoccupation with the rise and fall of empires.

Apart from manuscripts, some in his own hand, and his sister’s tombstone, little survives that is directly connected with Ibn Khaldun, although the writings of his friend Ibn al-Khatib are represented. Nevertheless, from around all the Mediterranean, a dozen or more countries have contributed items to build up the picture of the material world he would have known: plates such as those he might have used, mosque lamps, a traveler’s writing box, a set of nesting glasses, some beautiful examples of Granada silk and more.

In one section of his Autobiography, Ibn Khaldun wrote at length about the gifts he arranged to be sent to certain rulers on various occasions. These were an essential part of the diplomatic exchanges of the day, and fine silks played an important role. He also described his hunt for suitable presents to give Timur: He chose a one-volume copy of the Qur’an with an iron clasp, a pretty prayer rug, a copy of a famous poem (al-Burdah) and four boxes of his favorite Egyptian sweets—which he tells us were immediately opened and handed round. Similar items are on display.

|

| TOLEDO PRIMATE CATHEDRAL / EL LEGADO ANDALUSI |

| Detail from the personal standard of the Marinid sultan Abu al-Hasan ‘Ali, taken at the Battle of Salado in 1340. The invading army was defeated by the allied forces of Castile, led by Pedro i’s father, and Portugal. |

The world of Ibn Khaldun is also brought alive by photographs or architectural details of buildings he would have known, from the street on which he is believed to have lived in Tunis to the Castle of Ibn Salamah, now in ruins, where he retired for four years of relative peace to write his great work. The madrasahs, where he taught all across North Africa and in Cairo, are represented too—including, of course, al-Azhar, the great center of Islamic learning still functioning today.

The Christian world is also present to remind the visitor of what was going on in Europe in terms of art and intellectual achievement during the period Ibn Khaldun was writing. There are objects from China and Central Asia too, for besides the struggles for power among the Berber dynasties in North Africa and the Christian attempt to drive the Muslim colonizers from Spain, the great threat to civilization as Ibn Khaldun saw it was in fact posed by Timur. Hence the Central Asian steppe was an important part of the world picture from which his theories of the rise and fall of empires was formed. Taking advantage of Seville’s warm summer nights, the exhibition stays open until midnight. This enables visitors to wander through the courtyards of the palace, watch the moon reflect in the ornamental pools and inhale the scent of jasmine—a plant introduced by the Arabs and which Ibn Khaldun would have known.

In the evenings, a play about Ibn Khaldun is performed in the gardens, and across the façade of the palace there is a striking play of projected images: knights in armor, Mamluk horsemen, depictions of Dante and Timur, calligraphy in both Arabic and Latin, maps and landscapes taken from illuminated manuscripts.

TAXES

In the early stages of the state, taxes are light in their incidence, but fetch in a large revenue; in the later stages the incidence of taxation increases while the aggregate revenue falls off. …Now where taxes and imposts are light, private individuals are encouraged to actively engage in business; enterprise develops, because businessmen feel it worth their while, in view of the small share of their profits which they have to give up in the form of taxation. And as business prospers the number of taxes increases and the total yield of taxation grows. However, governments become progressively more extravagant and start to raise taxes. These increases [in taxes and sales taxes] grow with the spread of luxurious habits in the state, and the consequent growth in needs and public expenditure, until taxation burdens the subjects and deprives them of their gains. People get accustomed to this high level of taxation, because the increases have come about gradually, without anyone’s being aware of exactly who it was who raised the rates of the old taxes or imposed the new ones. But the effects on business of this rise in taxation make themselves felt. For businessmen are soon discouraged by the comparison of their profits with the burden of their taxes, and between their output and their net profits. Consequently production falls off, and with it the yield of taxation. The rulers may, mistakenly, try to remedy this decrease in the yield of taxation by raising the rate of taxes; hence taxes and imposts reach a level which leaves no profit to businessmen, owing to high costs of production, heavy burden of taxation and inadequate net profits. This process of higher tax rates and lower yields (caused by the government’s belief that higher rates result in higher returns) may go on until production begins to decline owing to the despair of businessmen, and to affect the population. The main injury of this process is felt by the state, just as the main benefit of better business conditions is enjoyed by it. From this you must understand that the most important factor making for business prosperity is to lighten as much as possible the burden of taxation on businessmen, in order to encourage enterprise by giving assurance of greater profits.

—tr. Issawi

|

One of the most remarkable achievements of this exhibition is its fine catalogue, coordinated under the auspices of the Granada-based El Legado Andalusí and the José Manuel Lara Foundations. It is in two volumes, with one dedicated specifically to the exhibition and the other a compilation of articles on aspects of Ibn Khaldun and his world written by scholars from a wide range of universities. (Fittingly, Ibn Khaldun’s home city of Tunis is particularly well represented.) It is, in fact, an anthology of the most up-to-date scholarship on Ibn Khaldun and his world.

AT QAL‘AT IBN SALAMAH

I had taken refuge at Qal‘at ibn Salamah… and was staying in the castle belonging to Abu Bakr ibn ‘Arif, a well-built and most welcoming place. I had been there for a long time…working on the composition of the Kitab al-‘Ibar to the exclusion of all else. I had already finished drafting it, from the Introduction to the history of the Arabs, Berbers and the Zanatah, when I felt the need to consult books and archives such as are only to be found in large towns, in order to check and correct the numerous citations that I had set down from memory. Then I fell ill…. Because of all this, I felt a great wish to be reconciled with the Sultan Abu al-‘Abbas and to go back to Tunis, the land of my forefathers, whose houses and tombs are still standing and where traces of them are still to be found.”

—tr. Abdessalam Cheddadi/Caroline Stone

|

Particularly interesting is the analysis of his manuscripts by Jumaâ Cheikha of the University of Tunis, who shows that the oft-repeated statement that Ibn Khaldun was not valued in the Muslim world is untrue: 195 surviving copies of his various books may not seem like much in the light of modern print runs, but by medieval standards it indicated success. Many works by more recent authors have come down to us in not more than a single copy.

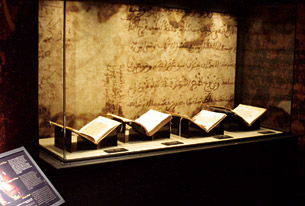

|

| EL LEGADO ANDALUSI |

| Copies of medical treatises and other works of science and history dating to Ibn Khaldun’s time are tangible reminders that—despite the turbulence of the 14th century—it was also a time of advances in knowledge and of fruitful cross-cultural exchange. |

As an homage to Ibn Khaldun, and one that would surely have given him pleasure, the organizers and especially Jerónimo Páez López, founder of El Legado Andalusí, have gone to immense trouble to ensure that places associated with Ibn Khaldun are all represented and different aspects of his world covered. It is very much to be hoped that the plans for the exhibition to travel to a number of different locations will come to fruition.

|

Caroline Stone divides her time between Cambridge and Seville. She is working with Paul Lunde on a translation of selections from The Meadows of Gold for Penguin Classics as well as a volume on the journeys of Ibn Fadlan and other Arab travelers to the north, to appear in 2007.

|

| Where not otherwise credited, translations from the Muqaddimah are from Charles Issawi’s An Arab Philosophy of History: Selections from the Prolegomena of Ibn Khaldun of Tunis (1332–1406) (revised edition 1987, Darwin Press, isbn 0-87850-056-1) or from Franz Rosenthal’s three-volume translation, The Muqaddimah (second edition 1967, Princeton University). | |

This article appeared on pages 28-39 of the September/October 2006 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

See Also: BOOKS, DIPLOMACY, EXHIBITIONS, HISTORIOGRAPHY, IBN KHALDUN, ABU ZAYD 'ABD AL-RAHMAN, KITAB AL-'IBAR, MUQADDIMAH, REAL ALCÁZAR, SEVILLE

Check the Public Affairs Digital Image Archive for September/October 2006 images.