Um importante artigo sobre os mitos e verdades da desindustrialização e as novas estruturas da competividade internacional entre grandes atores (o Brasil não se qualifica nesse cenário). PRA

While 2025 was, in USTR Jameison Greer’s phrasing, “the year of the tariff”, industrial policy served as a strong leitmotif. From the US-China rare earths saga to equity stakes, golden shares and prepurchase agreements, Trump 2.0 has wholly embraced the sort of muscular intervention into private markets that would have made the GOP of just a decade ago cry bloody murder.¹ Looking past this administration, JD Vance and Rubio, the two 2028 nominee frontrunners, both have Senate track records filled with bill proposals around industrial banks and domestic manufacturing promotion.

But for all the motion around creative applications of industrial policy in America, it’s been surprising to me how little thought has been applied to the big questions around these swings. Key questions I see unanswered include:

What should the long term goals of national industrial policy be?

What does it mean to be an economically secure nation? Where should marginal dollars be spent to promote economic security?

Just how important is manufacturing relative to services?

What are the tradeoffs involved in furthering these aims?

To kick us off, Chris Miller, Chip War author and reigning belt holder for most ChinaTalk appearances, published an excellent piece on what the core policy questions are for industrial policy. We’re rerunning this from his exellent new substack below.

Exploring these themes will be a focus of our coverage in 2026. Look out for essay contests coming in the next few weeks on this theme. Leave in the comments your ideas for what our first prompts should be!

The Economist, in a recent survey of Europe’s economic woes, sparked a minor controversy by urging the continent to adjust to intense Chinese competition in manufacturing by reorienting toward services. “De-industrialization,” it argued, “need not be synonymous with decay.”

The argument goes like this: rich economies are rich because of high value-add services. America is the least industrial (measured by manufacturing as % GDP) of all big economies, but also the richest. One reason that Germany and Japan are relatively more industrial is because they never developed much of a software industry. They’re more industrial partly because their manufacturers are relatively more successful (eg, their auto firms retained more market share the US ones over the past few decades) but also partly because they’ve underperformed in high value services.

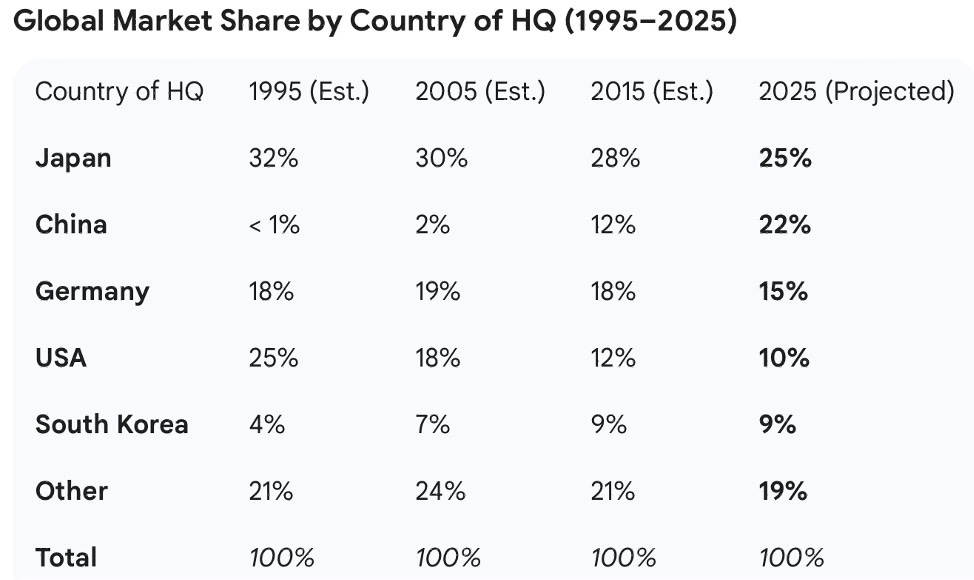

Here’s auto manufacturing, where the US has dramatically underperformed the trend (data from Gemini):

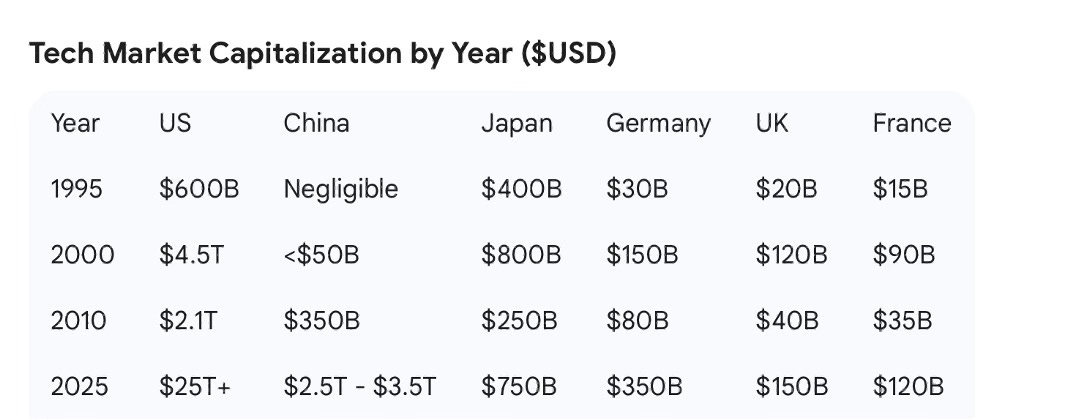

And here’s software market cap and market share, also from Gemini. Ask “would you rather have: 1) a world in which GM performed as well as Volkswagen over the past 30 years or 2) Silicon Valley?” the answer is obvious.

Perhaps that’s an unfair phrasing of the question, assuming that the only options were to either double down on an aged-out industrial base or to deindustrialize in favor of software.

Was there an alternative? Peter Thiel has quipped that we were promised flying cars and instead got 140 characters. Could we have redirected talent to produce less social media and more SpaceX? I’m unsure, though I’d note that Elon’s initial fortune came from enabling online shopping (PayPal) and Peter Thiel was an early Facebook investor. Palmer Luckey founded Anduril after he’d already sold a business to Facebook. It’s not easy to separate America’s titans of deep tech from the profits of the internet economy.

I’m a supporter of the “reindustrialize America” impulse. But I also haven’t seen clear thinking around the tradeoffs it implies. We need to prioritize when allocating people, dollars, and other scarce resources. So whether and when does manufacturing matter? Here are some ideas.

Jobs

I find completely unconvincing the theory, commonly hawked by politicians of both parties, that manufacturing is a good source of “jobs.” Even supposing that it’s true that manufacturing jobs pay better than service sector jobs on average (I haven’t yet parsed this data carefully), manufacturing is only ~10% of employment in the U.S. and so a 20% increase in manufacturing employment will be negligible at the economy-wide level. Moreover, the only way to manufacture in the U.S. cost effectively is to aggressively automate. So as a theory of policy, “manufacturing is good for jobs” makes no sense.

Driving productivity growth

I also don’t think much of the theory that you need a big manufacturing sector to drive productivity improvements in an advanced economy. If that were true, Germany would be richer and America poorer. But America has deindustrialized (manufacturing as % GDP) even as its economy has outperformed. I’m open to the idea that developing economies sometimes need manufacturing to drive productivity growth—a debate that has huge ramifications eg for India, but none for the United States.

The tech sector is a useful case. As Patrick McGee argues in Apple in China, America’s largest consumer tech firm is inextricably intertwined with China-based manufacturing. Perhaps hopelessly so. I worry a lot about the geopolitical implications of this. But I don’t worry much about the economic implications.

A decade or two after “capturing” Apple, Chinese firms still haven’t captured much economic value. Around a quarter of the bill of materials of an iPhone accrues to China-based suppliers, but generally for the lower margin components. A lot of the higher value manufacturing done in China is in factories owned by foreign firms, as Vishnu Venugopalan and I have explored.

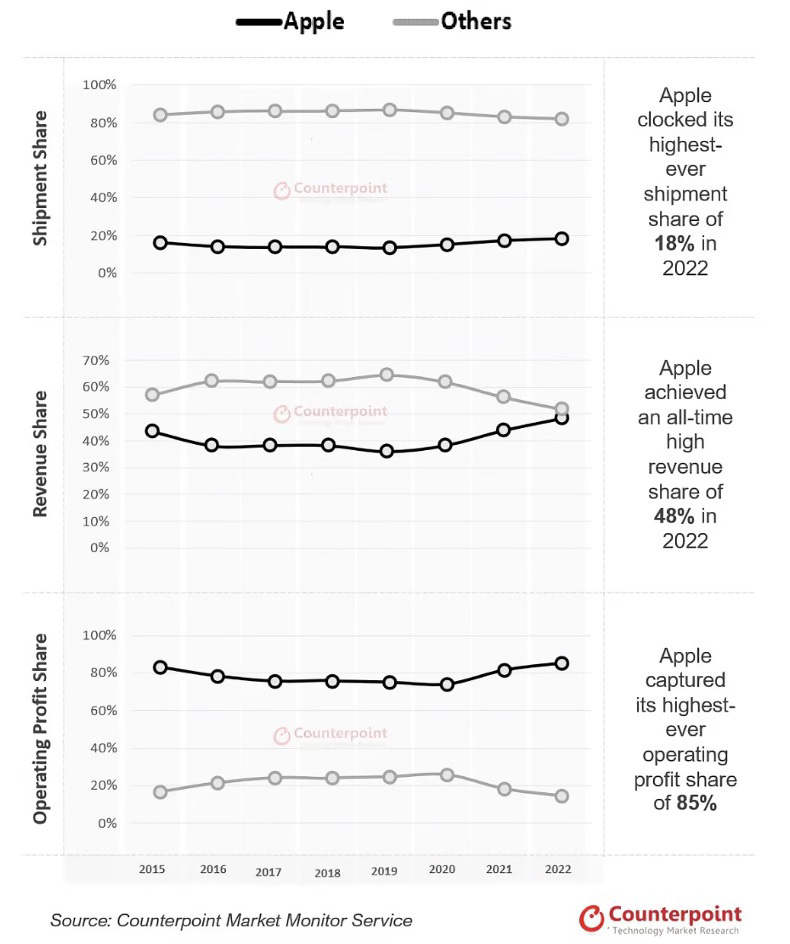

Apple still makes ~50% margins across the iPhone business. It makes ~80% of all global profits from selling smartphones, despite selling only a fraction of the world’s phones. Chinese brands—Oppo, Vivo, Xiaomi, Honor, etc—dominate the industry by units sold. Most of the world’s phones are assembled in their neighborhood. But these companies haven’t found a way to make much money. Samsung’s done better than the Chinese firms at profitability, but far worse than Apple, despite that Samsung is much “closer” to the manufacturing process, making displays, memory chips, logic chips, and other components itself. In other words, the smartphone company furthest from the manufacturing has made the most money, now for nearly two decades. It’s actually pretty shocking.

If you assume away geopolitics—which of course we can’t, more on this below— smartphones suggest that there’s no generalizable link between manufacturing, productivity improvements, and value extraction. I’m open to this dynamic existing in certain industries, but it doesn’t seem like a strong case for broad-based support for manufacturing.

Defense and geopolitical leverage

The best argument against The Economist’s embrace of deindustrialization came from Sander Tordoir, who wrote in a letter to the editor: “Europe will need drones and tanks, not just consultants.” The ability to make stuff has military and geopolitical importance.

The claim that manufacturing matters for geopolitical power is obvious in the abstract. We’ve all studied the “arsenal of democracy.” We’ve lived through economic warfare around manufactured products like chips and magnets.

Yet the policy relevant question is not “is manufacturing geopolitically useful?” but rather “given resource constraints and a preexisting factor allocation, how much should we spend to boost our manufacturing capabilities? Should we target a) pure defense, b) dual use, c) chokepoints, or d) across-the-board civilian production?”

We haven’t put much collective thought into the answers. We agree that chips and magnets matter, while t-shirts don’t. What we disagree about is everything in between.

Here’s President Trump:

I’m not looking to make t-shirts, to be honest. I’m not looking to make socks. We can do that very well in other locations. We are looking to do chips and computers and lots of other things, and tanks and ships.

And CFR President Michael Froman (and former USTR) on ChinaTalk earlier this month:

Can we take T-shirts and sneakers and toys from China without compromising our national security? I would think so.

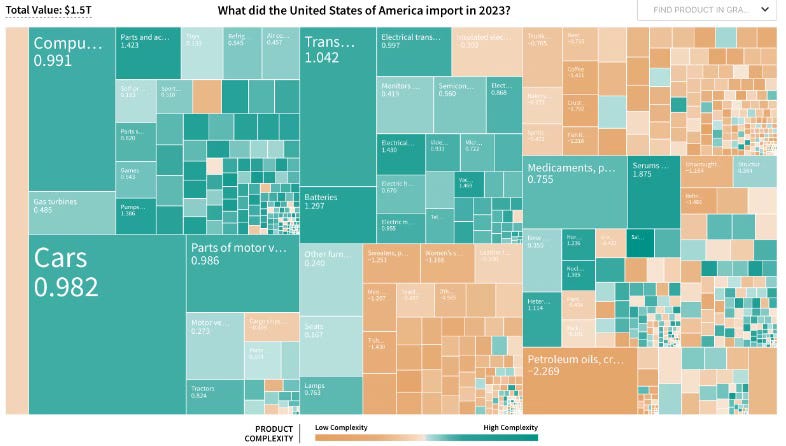

The problem is, there’s a whole lot of manufacturing that falls in between t-shirts and rare earth magnets. Of America’s ~$2 trillion in imports, only ~7% is textile products like clothes and furniture (using the excellent Atlas of Economic Complexity’s trade categorization.) Agricultural products are something similar. Toys are less than 2%. Games are 0.3%, sporting equipment 0.2%, and Christmas decorations are 0.14%. In other words: take out toys, textiles, t-shirts, and the like, and the U.S. is still importing a ton of manufactured goods.

The key remaining categories by complexity and scale are: cars, computers, phones, a wide variety of industrial and electronic machinery, chemicals and metal products. If you want to say something serious about reindustrialization, you need a view on these good. Should we be producing more of them?

Here’s a visualization: green goods are deemed by Harvard’s Atlas of Economic Complexity to be “complex” goods—roughly, high value. The yellow are simpler things produced by a larger number of trading partners, that are lower value and at lower risk of monopolization. As you’ll see, there’s a lot of green.

The scale of imported manufactures—including relatively complex, relatively higher-value added goods—illustrates the scale of trade offs around reindustrialization efforts. For reckoning with these trade offs as they relate to national security, I see a couple of hard-to-answer empirical questions.

What’s the risk a given product can be monopolized and used for leverage, like China’s done with rare earth oxides and magnets this year?

Economists have produced rough estimates of elasticities, but you often need deep supply chain knowledge to fully understand these dynamics. If it were easy, we wouldn’t see so many supply chain disruptions in the auto industry.

How shiftable is manufacturing capacity in a crisis?

One of the arguments in favor of building industrial capacity is that it can be repurposed if needed. Ford made tanks and planes during World War II. Yet how generalizable is such repurposing?

How tightly linked are today’s manufacturing ecosystems and tomorrow’s?

If losing today’s manufacturing capability also prevents a country from making tomorrow’s key products—and if benefits accrued not to a specific firm, but to a broad ecosystem—it might be reasonable to subsidize it. How strong are these ecosystem effects? Some good historical examples:

What’s the opportunity cost?

Even acknowledging the scale of China’s manufacturing dominance and the incapacity of our defense industrial base, we still must ask whether a marginal dollar is best spent on trying to shore up our manufacturing base versus buying defense-specific or other capabilities. Not that I wouldn’t gladly take some more manufacturing capacity, if it were free. But it isn’t. We’re constrained by labor, electricity, capital, etc, as anyone building a factory in the U.S. will immediately report.

See the recent riff I had refelcting on Solyndra with Rahm Emanuel. Rahm: To your point about socialism — Solyndra. We invested in this new solar firm and everyone’s like, “Oh my God, oh my God!”, and here are these guys investing in and putting public money in companies with zero operating capacity.”