The American Way of Economic War

Is Washington Overusing Its Most Powerful Weapons?

By Paul Krugman

Foreign Affairs, January/February 2024 Published on December 6, 2023

Suppose that a company in Peru wants to do business with a company in Malaysia. It should not be hard for the firms to make a deal. Sending money across national borders is generally straightforward, and so is the international transfer of large quantities of data.

But there’s a catch: whether or not the companies realize it, their transactions of both financial information and data will almost certainly be indirect and will probably pass through the United States or institutions over which the U.S. government has substantial control. When they do, Washington will have the power to monitor the exchange and, if desired, stop it in its tracks—to stop, in other words, the Peruvian company and the Malaysian company from doing business with each other. In fact, the United States could prevent many Peruvian and Malaysian companies from trading goods in general, largely cutting the countries off from the international economy.

Part of what undergirds this power is well known: much of the world’s trade is conducted in dollars. The dollar is one of the few currencies that almost all major banks will accept, and certainly the most widely used one. As a result, the dollar is the currency that many companies must use if they want to do international business. There is no real market in which the Peruvian company could exchange Peruvian soles for Malaysian ringgit, so local banks facilitating that trade will normally use soles to buy U.S. dollars and then use dollars to buy ringgit. To do so, however, the banks must have access to the U.S. financial system and must follow rules laid out by Washington. But there is another, lesser-known reason why the United States commands overwhelming economic power. Most of the world’s fiber-optic cables, which carry data and messages around the planet, travel through the United States. And where these cables make U.S. landfall, Washington can and does monitor their traffic—basically making a record of every data packet that allows the National Security Agency to see the data. The United States can therefore easily spy on what almost every business, and every other country, is doing. It can determine when its competitors are threatening its interests and issue meaningful sanctions in response.

Washington’s spying and sanctioning is the subject of Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy, by Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman. This revelatory book explains how Washington came to command such awesome power and the many ways it deploys this authority. Farrell and Newman detail how September 11 pushed the United States to begin using its empire and how its many constituent parts have come together to constrain both China and Russia. They show that although other states may not like Washington’s networks, escaping them is extremely difficult.

The authors also demonstrate how, in the name of security, the United States has created a system that is often abused. “To protect America, Washington has slowly but surely turned thriving economic networks into tools of domination,” Farrell and Newman write. And as their book makes clear, the United States’ efforts to dominate can cause tremendous damage. If Washington deploys its tools too often, it might prompt other countries to break up the current international order. The United States could push China to cut itself off from much of the world economy, slowing global growth. And Washington might use its authority to punish states and people that have done nothing wrong. Experts must therefore think about how to best constrain—if not quite contain—the United States’ empire.

DATA AND DOLLARS

The United States’ centrality in global finance and data transmission is not entirely unprecedented. The world’s leading power has always had outsize control over the world’s economy and communication networks. At the beginning of the twentieth century, for example, the British pound played a key role in many international transactions, and a plurality of all global submarine telegraph cables passed through London.

But 2023 is not 1901. Today’s era is defined by what some economists call “hyperglobalization.” The world is far more intertwined than it was a century ago. It is not just that global trade now makes up a larger share of economic activity than in the past; it is also that the complexity of international transactions is far greater than ever before. And the fact that so many of these transactions pass through banks and cables that the United States controls gives Washington powers that no government in history has possessed.

Many lay observers, and quite a few professional commentators, imagine that this dominance affords the United States great economic advantages. But economists who have done the math generally do not believe that the dollar’s special position makes more than a marginal contribution to the United States’ real income—the amount of money Americans make after adjusting for inflation. There do not appear to be any studies of the economic benefits that come from hosting fiber-optic cables, but those benefits, too, are likely to be small (especially because many of the profits that come from transporting data are probably booked in Ireland or other tax havens). But Farrell and Newman show that U.S. control of the world economy’s chokepoints does give Washington new ways to project political influence—and that it has seized on them.

The United States began capitalizing on these powers, the authors argue, after the 9/11 attacks in 2001. Before, American officials had been inhibited in exercising U.S. economic might by fears of overreach. But officials quickly realized they could have been following Osama bin Laden’s financial transactions in a way that would have revealed the terrorist’s plans and that they could have used their financial influence to disrupt al Qaeda’s operations. And so, after the terrorist group struck, Washington put its concerns aside. It expanded both its financial surveillance and its use of sanctions.

John Lee

For policymakers, exercising these powers proved easy. The dollars used in international transactions are not bundles of cash but bank deposits, and almost every bank that keeps such deposits must have a foot in the U.S. financial system in case it needs access to the Federal Reserve. As a result, banks around the world try to stay in the good graces of U.S. officials, lest Washington decide to cut them off. The story of Carrie Lam, the China-appointed former chief executive of Hong Kong, provides a case in point. As Farrell and Newman write, after the United States sanctioned Lam for human rights violations, she was unable to get a bank account anywhere, even at a Chinese bank. Instead, she had to be paid in cash, keeping piles of money at her official residence.

A less picturesque—but far more consequential—example of U.S. power is the way Washington co-opted the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, better known as SWIFT. The organization serves as the messaging system through which major international financial transactions are made. Notably, it is based in Belgium, not the United States. But because so many of the institutions behind it rely on U.S. government goodwill, it began sharing much of its data with the United States after the 9/11 attacks, providing a Rosetta stone that Washington could use to track financial transactions worldwide. In 2012, the U.S. government was able to use SWIFT and its own financial power to effectively cut Iran out of the world financial system, and to brutal effect. After the sanctions, Iran’s economy stagnated, and inflation in the country reached roughly 40 percent. Eventually, Tehran agreed to cut back its nuclear programs in exchange for relief. (In 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump scuttled the deal, but that’s another story.)

That is the kind of power the United States gets from its control over financial chokepoints. But as Farrell and Newman show, what the United States can do with its control over data chokepoints is arguably more remarkable. At many, or perhaps all, of the places where fiber-optic cables enter American territory, the U.S. government has installed “splitters”: prisms that divide the beams of light carrying information into two streams. One stream goes on to the intended recipients, but the other goes to the National Security Administration, which then uses high-powered computation to analyze the data. As a result, the United States can monitor almost all international communication. Santa may not know whether you’ve been bad or good, but the NSA probably does.

Other countries, of course, can and do spy on the United States. China, in particular, works hard to intercept advanced American technology. But no one does spying better than Washington, and despite Beijing’s best efforts, China has not been able to steal enough secrets to match U.S. prowess. As Farrell and Newman point out, the United States still dominates crucial intellectual property—not so much the software that runs current semiconductor chips, but the software used to design complex new semiconductors, which is still an essential market. “U.S. intellectual property,” the authors declare, winds “through the entire semiconductor production chain, like a fisherman’s longline with barbed and baited hooks.”

ALL THAT POWER

There are many illustrative examples of Washington weaponizing its underground empire, including the sanctioning of both Lam and Iran. But the one that may best show how all three elements of the empire—control over dollars, control over information, and control of intellectual property—come together is the astonishingly successful takedown of the Chinese company Huawei.

Just a few years ago, American officials and foreign policy elites were in a panic about Huawei. The company, which has close ties to the Chinese government, seemed poised to supply 5G equipment to much of the planet, and U.S. officials worried this spread would effectively give China the power to eavesdrop on the rest of the world—just as the United States has done.

So Washington used its interlocking empire to cut Huawei off at the knees. First, according to Farrell and Newman, the United States learned that Huawei had been dealing surreptitiously with Iran—and therefore violating U.S. sanctions. Then, it was able to use its special access to information on international bank data to produce evidence that the company and its chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou (who also happened to be the founder’s daughter), had committed bank fraud by falsely telling the British financial services company HSBC that her company was not doing business with Iran. Canadian authorities, acting on a U.S. request, arrested her as she was traveling through Vancouver in December 2018. The U.S. Department of Justice charged both Huawei and Meng with wire fraud and a number of other crimes, and the United States used restrictions on the export of U.S. technology to pressure Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, which supplies many crucial semiconductors, into cutting off Huawei’s access to the most advanced chips. Beijing, meanwhile, detained two Canadians in China and essentially held them hostage.

Santa may not know whether you’ve been bad or good, but the NSA probably does.

After spending almost three years under house arrest in Canada, Meng entered into an agreement in which she admitted to many of the charges and was allowed to return to China; the Chinese government then released the Canadians. But by that point, Huawei was a much-diminished force, and the prospects for Chinese dominance of 5G had vanished—at least in the near term. The United States had quietly waged a postmodern war on China, and won.

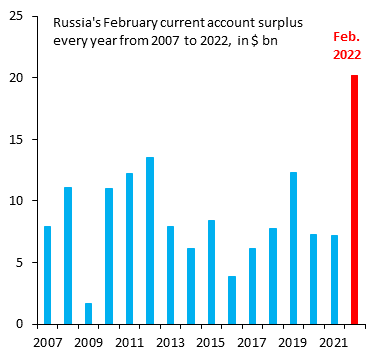

At first glance, this victory could seem like unambiguously good news. Washington, after all, limited the technological reach of a dictatorial regime without having to use force. The United States’ ability to cut North Korea off from much of the world financial system, or its successful sanctioning of Russia’s central bank, might also prompt rightful cheers. It is hard to be outraged by the United States’ use of hidden powers to block global terrorism, break up drug cartels, or hobble Russian President Vladimir Putin’s attempt to subjugate Ukraine.

Yet there are clearly risks in the exercise of these powers. Farrell and Newman, for their part, are worried about the possibility of overreach. If the United States uses its economic power too freely, they write, it could undermine the basis of that power. For example, if the United States weaponizes the dollar against too many countries, they might successfully band together and adopt alternative methods of international payment. If countries become deeply worried about U.S. spying, they could lay fiber-optic cables that bypass the United States. And if Washington puts too many restrictions on American exports, foreign firms might turn away from U.S. technology. For example, Chinese designed software may not be a match for the United States’, but it is not too hard to imagine some regimes accepting inferior quality as the price for getting out from under Washington’s thumb.

So far, none of this has happened. Despite endless breathless commentary about the potential demise of the dollar, the currency reigns supreme. In fact, as Farrell and Newman write, the dollar endured despite the “vicious stupidity” of the Trump administration. Laying fiber-optic cables that bypass the United States might be easier to accomplish, and people who are not technologists do not really know how easily U.S. software can be replaced. Still, Washington’s hidden power seems remarkably durable.

Reflections off of a currency exchange board in Buenos Aires, Argentina, September 2019

Agustin Marcarian / Reuters

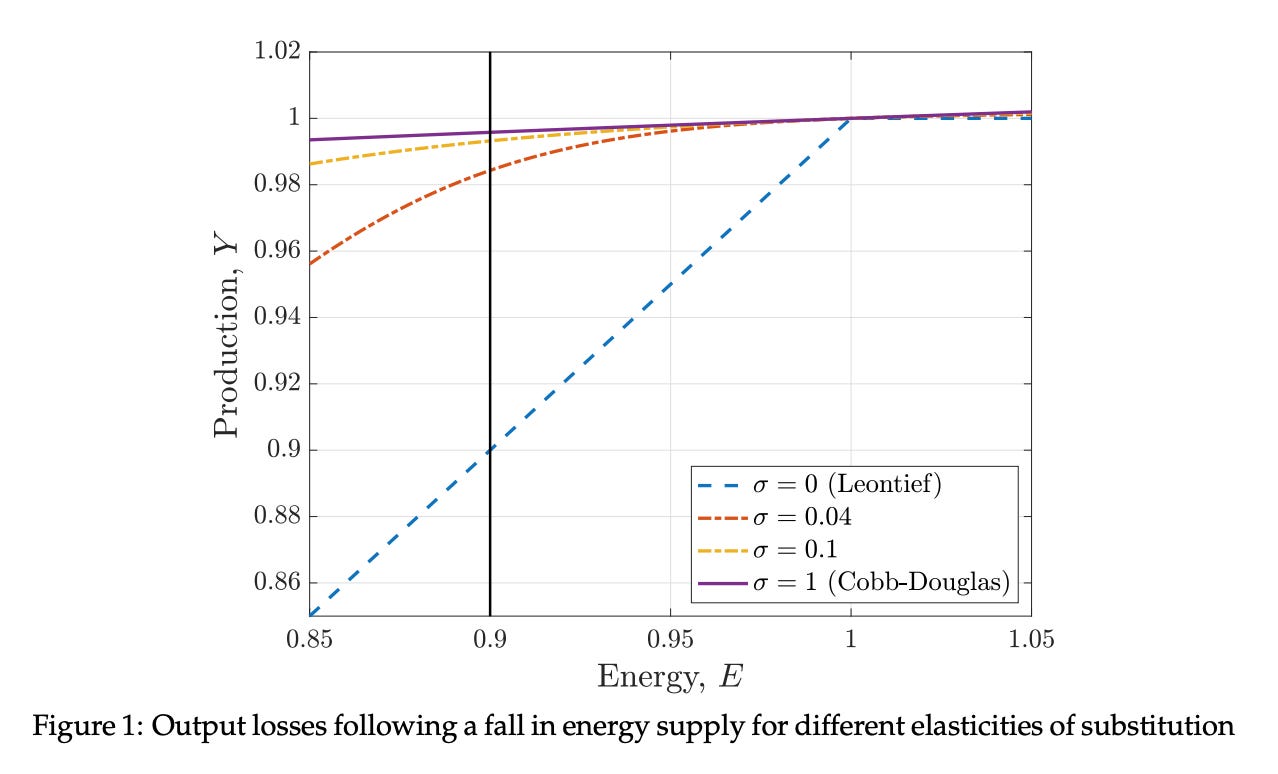

But that does not mean there are no limits to how far the United States can push. Farrell and Newman worry that China, which is an economic superpower in its own right, might decide to “defend itself by going dark”: cutting off international financial and information linkages to the wider world (which it already does to some extent). Such an action would have significant economic costs for everyone. It would degrade China’s role as the workshop of the world, which—in its own way—might be as hard to replace as the global role of the U.S. dollar.

There is also the obvious risk that countries that lose wars without gun smoke could lash out by waging wars with gun smoke. As Farrell and Newman write, the weaponization of trade is one of the factors that contributed to World War II: Germany and Japan both engaged in wars of conquest, in part, to secure access to raw materials they feared might be cut off by international sanctions. The nightmare scenario for today would be if China, fearful that it is being marginalized, were to strike back by invading Taiwan, which plays a key role in the global semiconductor industry.

But even if the United States does not overuse its underground empire or provoke hot conflict, there is still a major reason to worry about Washington’s dramatic economic and data power: the United States will not always be in the right. Washington has made plenty of unethical foreign policy decisions, and it could use its control over global chokepoints to harm people, companies, and states that should not come under fire. Trump, for example, slapped tariffs on Canada and Europe. It is not hard to imagine that if he were to win a second term, he would try to hobble the economies of European states critical of his foreign or even domestic policies. One does not have to see everything through the lens of the Iraq war or insist that the United States somehow forced Putin to invade Ukraine to be worried about the underground empire’s lack of accountability.

RULES OF THE ROAD

Farrell and Newman do not propose policies that could mitigate these risks, other than suggesting that the underground empire deserves the same kind of sophisticated thinking once devoted to nuclear rivalries. Still, by highlighting how the nature of global power has changed, the book makes an enormous contribution to the way analysts think about influence. And policymakers and researchers should begin formulating plans for fixing these problems.

One possible resolution would be to create international rules for the exploitation of economic chokepoints, along the lines of the rules that have constrained tariffs and other protectionist measures since the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, in 1947. As every trade economist knows, the GATT (and the World Trade Organization that grew out of it) does more than just protect nations from each other. It protects them from their own bad instincts.

It will be hard to do something similar with newer forms of economic power. But to keep the world safe, experts should try to come up with regulations that have the same moderating effect. The stakes are too high to let these challenges go unaddressed.

- PAUL KRUGMAN, winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Economics, is Distinguished Professor of Economics at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.