People walk past street art in Rio de Janeiro this month. (Pilar Olivares/Reuters) |

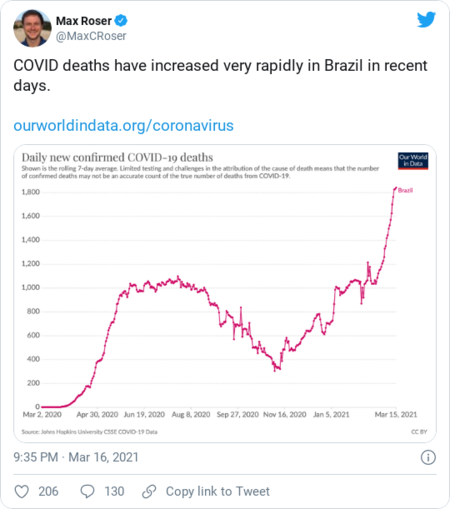

In the tortuous course of the coronavirus pandemic, there has been at least one constant: Latin America’s most populous nation has not handled it well. Brazil lags behind only the United States in coronavirus-related deaths and infections. But the latter is starting to battle its way out of the pandemic; in Brazil, the outbreak is now worse than it has ever been. The country on Tuesday reported close to 3,000 deaths, a spike that accelerated this month. In the past week, Brazil posted a record of 12,888 new deaths and more than 467,944 new cases, according to Johns Hopkins University figures. Experts warn that Brazil’s hospital system is on the brink of collapse, with occupancy peaking near or even pushing past capacity in over half the states of the country. Rather than going up, the daily numbers of administered coronavirus tests — key to tracking and stopping a surge in cases — have declined dramatically since December. Part of the problem is the emergence of a more virulent coronavirus variant in Brazil, one whose rapid spread since January has raised global alarm. “If Brazil is not serious, then it will continue to affect all of the neighborhood there — and beyond,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the World Health Organization, warned earlier this month. “This is not just about Brazil. It’s about the whole Latin America, and even beyond.” Even in communities that are developing greater levels of immunity, an uncontrolled outbreak can still give rise to dangerous variants — and scientists fret that Brazil is incubating possibly deadlier new strains. A patchwork of inconsistent curfews and lockdowns in states and cities failed to stave off the crisis many Brazilian medical workers feared would come. Doctors and health officials are now battling against a rising tide. “Patients are being transferred from state to state — sometimes traveling hundreds of miles — in a nationwide hunt for hospital resources,” my colleague Terrence McCoy wrote last week. “Without ventilators, nurses have pumped infected patients’ lungs manually. Cemeteries are running out of space to put the bodies. Refrigerated containers wait outside hospitals to take the overflow. People all over the country are dying at home, unable to get treatment.”  | | |

It’s impossible to overlook the role played by Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. The far-right firebrand bumbled through the pandemic— famously deeming the coronavirus little more than a “measly flu” a year ago and, more recently in December, declaring that the outbreak had reached its “tail end.” He contracted the virus himself but continued to tout unproven remedies and raged against social distancing measures and other precautions advocated by regional officials and his political adversaries. Under Bolsonaro’s watch, Brazil “succumbed to denialism, disorganization, apathy, hedonism and medical quackery,” wrote McCoy. In an illustration of the chaos, Bolsonaro announced this week that he would be appointing a new health minister — the country’s fourth since the pandemic began. The first two fell afoul of the president after questioning his leadership and covid-era decision-making. The third, an active-duty general with no medical training, is now being investigated by the country’s top court for alleged neglect that led to the collapse of the health system in Amazonas state earlier this year. During a briefing Tuesday, Marcelo Queiroga, a cardiologist who will transition into the role of health minister in the coming days, reiterated his loyalty to Bolsonaro. “The president is very worried about the situation,” he said. Critics wonder if that’s true. Brazil’s lack of effective national coordination on the pandemic is, in part, Bolsonaro’s fault. He and his allies initially pushed misinformation downplaying the threat of the virus and the efficacy of social distancing and masks. Later, Bolsonaro questioned the value of vaccines, stoking anti-Beijing sentiment even as a Chinese vaccine was undergoing trials in Brazil. Last October, he blocked federal government plans to purchase tens of millions of doses of the Sinovac vaccine. On this front, Bolsonaro had a fellow traveler in former president Donald Trump, who similarly scorned covid-era lockdowns and sought to blame his domestic rivals, as well as China, for the woes of the pandemic. Last year, the Trump administration also pressured Brazil to not obtain the Russian Sputnik V vaccine for its population. But with Trump gone and infections spiking, Bolsonaro is in the midst of a humiliating about-face. His government announced last week that it had ordered 10 million doses of the Russian vaccine. And it had to go to China, cap in hand, to request tens of millions of doses of a Chinese vaccine, as well as the raw materials to mass produce it on Brazilian soil.  | | |

“China spent months batting away resentment and distrust as the place where the pandemic began, but in recent weeks its diplomats, pharmaceutical executives and other power brokers have been fielding scores of requests for vaccines from desperate officials in Latin America, where the pandemic is taking a devastating toll that grows by the day,” noted the New York Times. “Beijing’s ability to mass-produce vaccines and ship them to countries in the developing world — while rich countries, including the United States, are hoarding many millions of doses for themselves — has offered a diplomatic and public relations opening that China has readily seized.” Meanwhile, in Brazil’s turbulent domestic political scene, Bolsonaro’s mismanagement has presented a new opening for his main rival. Former leftist president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva scorned Bolsonaro’s “moronic” handling of the crisis. “This country is in a state of utter tumult and confusion because there’s no government,” Lula declared last week, lamenting the lives that could have saved and warning that “covid is taking over the country.” Brazil’s medical workers are desperately trying to prevent that from happening. “We’re trying to help people but this disease is much faster and more aggressive than the tactics we’ve been using,” André Machado, an infectious-disease specialist in the city of Porto Alegre, told the Guardian. “It’s like we’re flogging a dead horse. This disease is going to kill many more people in Brazil.” |