University Discovered 1648 Bond that Still Pays Interest – And they Collected!

Experts at Yale University discovered a Dutch water bond from 1648 that amazingly still pays interest. At some point or another, people usually hear about some of the outrageous bond agreements to which persons have been subjected over the years. That said, hearing about a bond which was originally issued in the 17th century yet is still accruing interest 300 years later doesn’t happen often: in fact, some might argue that it’s impossible. Well, that’s not quite the case – it would seem that there isn’t just one, but a few bonds issued in the 1600s which have stood the test of time and are still very much relevant to the respective payers’ pockets.

YaleNews revealed that a water bond dating as far back as 1648 still contractually binds the obligated parties to pay annual interest today. Upon its discovery and subsequent analysis of its terms and agreements, reports indicate that at the time of its execution, the bond operated as a perpetual bond.

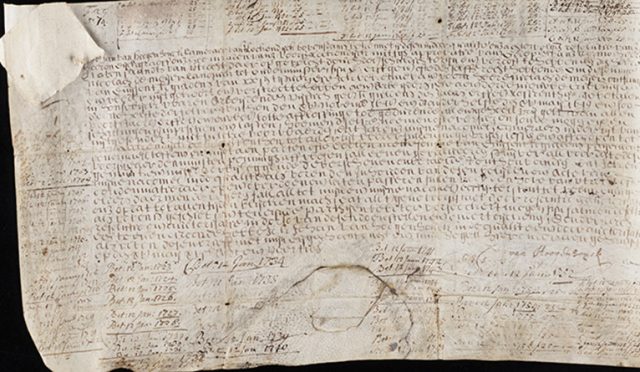

The original clauses of the agreement bound the payer to “5 percent interest in perpetuity,” a rate which was later lowered to 3.5 percent and then 2.5 percent respectively in the 1600s. At the time, physical notations of interest payments were inscribed on the bond as they were made as a means of recording them. Being of Dutch-origin and made out of goatskin, when the bond was issued, it was apparently made out to Mr. Niclaes de Meijer, a man who was ordered to pay the “sum of 1000 Carolus Guilders of 20 Stuivers a piece.”

This bond was issued in 1648 by a Dutch water board to finance improvements to a local dike system. A perpetual bond, it continues to pay interest. Photo courtesy of Yale News.

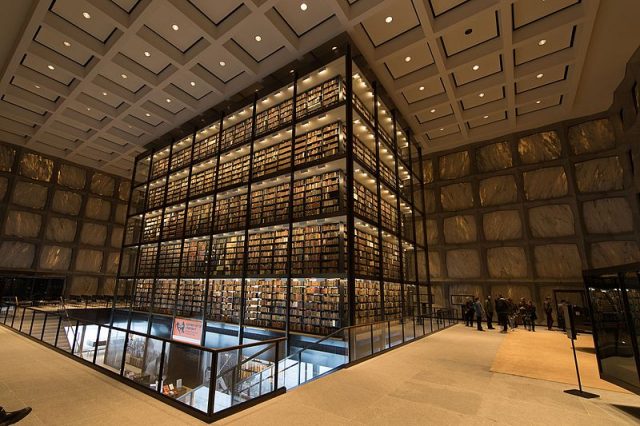

The manuscript was filed at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library in 2003 after Yale managed to come into possession of it. After Timothy Young, the curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts at the library, conferred with a Dutch water authority named Stichtse Rijnlanden, not only did he discover that this bond was only one of five ever found, all five of them were administered by the Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams.

Beinecke rare book library at Yale. Photo by Michael Kastelic CC by SA-4.0

This entity was actually a water board which comprised a combination of highly-esteemed citizens and landowners. Apart from collecting the interest payments, the board oversaw a number of man-made constructions, including canals and dikes. Based on YaleNews’ report, the money collected served to compensate workers who had just completed a project in which they had to construct a formation of piers located close to a bend in one of the rivers. The project was supposed to help prevent erosion by assisting the river in properly regulating its flow.

In 2015, when Timothy Young returned from meeting with the relevant Dutch authority, he also brought back with him 12 years of back interest which was owed on the bond, a total which amounted to approximately 136.20 euros. Prior to 2015, the last time that the bond payments were collected was in 2003 when Yale first acquired it. At that time, as the reports states, “Geert Rouwenhorst, professor of corporate finance and deputy director of the International Center for Finance, took the bond back to the Netherlands to collect 26 years of back interest.”

Related Video: The modern day revival of the Knights Templar

https://youtu.be/gb5U053HP6g

Rouwenhorst was quite surprised that such a bond hadn’t been deemed null and void yet, going on to say “Yale’s bond is an extremely early example of a security that was issued without maturity and still pays interest. One ought to be astounded that such a thing exists.”

That said, when the bond initially came into Yale’s possession, the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library did experience some difficulty in categorizing it considering that the bond was still very much valid.

According to Young, in order for the bond to remain valid, “we need to take it to the issuing authority in the Netherlands every couple of decades to collect the interest, but unless we’re loaning an item to another institution, we don’t allow collection material to leave the library.” For this reason, authorities were a bit divided as to how to best proceed with the filing of the document.

However, later on, something happened which enabled the relevant parties to come to an agreement. In 1944, the vellum no longer had any more space where the new interest payments could have been recorded. As a result, authorities elected to add a paper addendum which served to record future payments, a paper which they allowed to be sent to the Netherlands in order to retrieve and record the necessary payments.

At present, the bond is considered a bearer bond as anyone who shows the attached addendum to the authority in charge of issuing the payment is allowed to accept it.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário