Covid-19’s latest victim: Hungary’s democracy

Democracy Digest, March 25, 2020

Covid-19 is about to claim a new victim: Hungary’s democracy, argues Dalibor Rohac, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

The country’s parliament is set to adopt a new law that will give the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban a legal mandate to rule by decree, without any sunset clause and without parliamentary oversight. The government initially sought to fast-track the legislation and adopt it already on March 24, but it lacked the supermajority needed to accelerate the proceedings. The party, however, does not lack the votes to ensure that the legislation is passed through the normal legislative process a few days later, he writes for The Washington Post.

The brazenness of Orban’s power grab is without parallel in recent European history, Rohac adds.

Orban and Russia’s Vladimir Putin are leading practitioners of the art of political imitation, the subject of a recent book.

Russia’s political development since the end of the Cold War is central to Ivan Krastev and

Stephen Holmes’s insightful and important The Light That Failed, which examines the rise of authoritarianism and the decline of liberal democracy, notes Aryeh Neier, president emeritus of the Open Society Foundations and author of The International Human Rights Movement: A History.

Russian officials often attributed major responsibility for color revolutions in countries of the former Soviet Union to U.S.-government–funded institutions such as the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the National Democratic Institute, and the International Republican Institute. (He also blamed my institution, the Open Society Foundations, for contributing to these developments), he writes for The New Republic:

Putin saw support that these bodies had provided to like-minded organizations in these countries as thwarting his efforts to reconstitute the Soviet Union, at least as a unified bloc under Kremlin leadership. Russian legislation adopted in 2012 required nongovernmental organizations that accepted foreign funds to declare themselves to be “foreign agents,” delegitimizing them. Additional legislation adopted subsequently imposed further restrictions on Russian organizations conducting “political activities”—broadly defined—that received funds from the United States and other foreign donors. Putin has called the collapse of the Soviet Union the greatest catastrophe of the twentieth century. As he believed that American institutions played a part in frustrating his efforts to reverse that catastrophe, he had ample incentive to engage in imitative reprisals.

Of course, the manner in which Russia intervened in U.S. elections in 2016 differed from the role played by bodies such as the National Endowment for Democracy in elections in the former Soviet Union, Neier adds. It is one thing to fund a program for the training of election observers; it is quite another to establish fake social media accounts to disseminate false rumors and smear particular candidates.

Of course, the manner in which Russia intervened in U.S. elections in 2016 differed from the role played by bodies such as the National Endowment for Democracy in elections in the former Soviet Union, Neier adds. It is one thing to fund a program for the training of election observers; it is quite another to establish fake social media accounts to disseminate false rumors and smear particular candidates.

Authoritarian leaders are constantly searching for scapegoats, working to rile up the fears of their populace, and trying to tighten their grips, note the Atlantic Council’s Melinda Haring and Doug Klain.

To them, the coronavirus pandemic is a bonanza—the liberal democracies that would typically call them out for their violence, repression, and racism are distracted, with the necessities of stopping the virus in their home countries, they write for The National Interest. If these strongmen go unchecked, the COVID crisis may end with all of us emerging to find a world in which authoritarianism triumphs. More political prisoners, more presidents-for-life, and more despotism.

As we witness democratic backsliding around the world, Lawfare is releasing a two-part podcast series on the state of global democracy, notes Jen Patja Howell. In the first segment, Benjamin Wittes interviews Alina Polyakova and Torrey Taussig about “The Democracy Playbook” and strategies for fighting illiberal political movements.

For this episode, David Priess spoke with Michael Abramowitz and Sarah Repucci of Freedom House.

RTWT

Viktor Orbán is

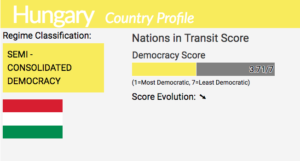

Viktor Orbán is This year Freedom House deemed Hungary only “partly free,” the first time in its history an EU member state has been denied the designation “free.”

This year Freedom House deemed Hungary only “partly free,” the first time in its history an EU member state has been denied the designation “free.” “You know the growth rates of Italy and some other European countries are much lower than Hungary’s. The Hungarian government is in a certain way very pro-business and is happy to attract business wherever it comes from with low taxes or longer working hours,” he adds.

“You know the growth rates of Italy and some other European countries are much lower than Hungary’s. The Hungarian government is in a certain way very pro-business and is happy to attract business wherever it comes from with low taxes or longer working hours,” he adds. In east-central Europe, the notion of “illiberal democracy” — a regime in which one party claiming a monopoly on national identity and tradition maintains itself permanently in power — has become part of the political landscape,

In east-central Europe, the notion of “illiberal democracy” — a regime in which one party claiming a monopoly on national identity and tradition maintains itself permanently in power — has become part of the political landscape,