ChinaTalk

How Will the CCP Respond to Protests?

"Students and people are making speeches and articulating why they are doing what they are doing. It's very difficult for Xi to claim that he didn't get the right message."

Ling Li (@lingli_vienna), lecturer at the University of Vienna, joined us on Monday, November 28 to discuss:

The origins and evolution of Covid Zero;

Different paths the CCP could take to cracking down;

What the protests tell us about modern China.

How Zero Covid Came to Be

Ling Li: When talking about the historical development of the Covid policy, the key point to remember is when the rest of the world had gradually opened up in the summer, China still insisted on the Zero Covid policy. Inspired by success in the earlier phase of the pandemic — the phase after the initial breakout in 2020 in Wuhan, mainly in the second half of 2020 and most of 2021 — this policy was advertised by the party as the secret of China's victorious war against the pandemic, which could be delivered only in China thanks to its unique political system and leadership.

This past summer, there were two interpretations of the future development of the policy. [The first was that] the policy was to stay forever as a permanent method for social control. The second [was] that the policy had to be kept in place because of the 20th Party Congress. Zero Covid policy would help to eliminate any nasty surprises that would otherwise ruin the celebratory mood and tarnish the spectacles of the Congress. Just imagine what an embarrassment it would have been if what happened yesterday had happened during the Party Congress!

Before the 20th Party Congress, both interpretations looked possible to me. But soon after the Congress, the newly elected Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) authorized a new policy: “20 Measures to Optimize the Covid Control Policy”, which contains a number of measures that are aimed at easing up the lockdown: lifting the citywide 48-hour mandatory PCR test, free access to grocery stores in some places without scanning your code, and easing up international travels. Obviously, the 20 measures are far from being entirely opened up. It has a heavy emphasis on partial lockdown measures, which is natural because any sensible transition is expected to be gradual. But it has, nevertheless, shown that the Party has not locked itself in the lockdown policy just for the convenience of political control. It also shows that the Party is willing to open up when the condition is right.

The number of infection cases skyrocketed in the last few weeks and the policy was quickly reversed, which makes me believe that the Party has a genuine concern that an immature open-up will make the mortality rate unbearable. This is a difficult phase that many countries have experienced, and the fact that it is difficult does not mean it is not viable or has no recourse. Nor does it mean that one can survive the crisis simply by hiding out and continuing with the lockdown. The two key issues in overcoming or alleviating the pain of the opening-up process are vaccination and the increase of medical treatment capacity. From the reports that I have access to at present, no significant improvement has been made in this direction. There still seems to be no result of a domestically developed mRNA vaccine. In contrast, considerable resources have been continuously poured in to enforce the lockdown measures, to reinstate the PCR test, and now to crack down on the protests and maintain social stability.

This makes me wonder whether the decision-makers, at both policymaking and policy-implementation levels, have been captured by the business interests of the Covid-related industries, who seem to have the most to gain from a prolonged lockdown policy. These industries include PCR testing, constructors and operators for makeshift hospitals, and other auxiliary services. These groups seem to gain most from [the] Zero Covid policy given the sheer size of the gigantic demands for their services.

Who owns these companies? What’s their relationship with the licensing authority? Anything smells like corruption?

Does any member of the Covid-control decision-making body in Beijing have a business interest in this?

Beijing’s Political Calculus

Jordan Schneider: So what's more intolerable to the Party? Seeing a million Chinese people die over the course of two months, or continued street protests?

Let's talk a little bit about the relationship between Covid Zero and the protests. Expectations were raised after the Party Congress, and then continued lockdowns in the face of spiking numbers gave a lot of folks a sense of hopelessness — that this was, in fact, never going to end. Then, over the past few days, we saw the fire in Xinjiang, followed by protests nationwide. How do you think the street actions have potentially changed the calculus of decision-makers in Beijing?

Ling Li: I assume it's a still ongoing process, and I hope the new PSC members in Beijing are coming together and trying to get out of the crisis in some way.

One reason for the PSC to meet is in the face of [a] national crisis, and the protests we're seeing right now certainly qualify. There's so much resemblance and parallel that we can draw [between] the protests now and 1989, when protests started to spread across the nation — starting from the universities, and then [spilling] over to other social sectors. There will be a concern of fear that history will repeat itself, but I doubt it will. In 1989, if my memory serves correctly, before the Army was brought in for the crackdown the local police did not involve themselves in repressing the protesters.

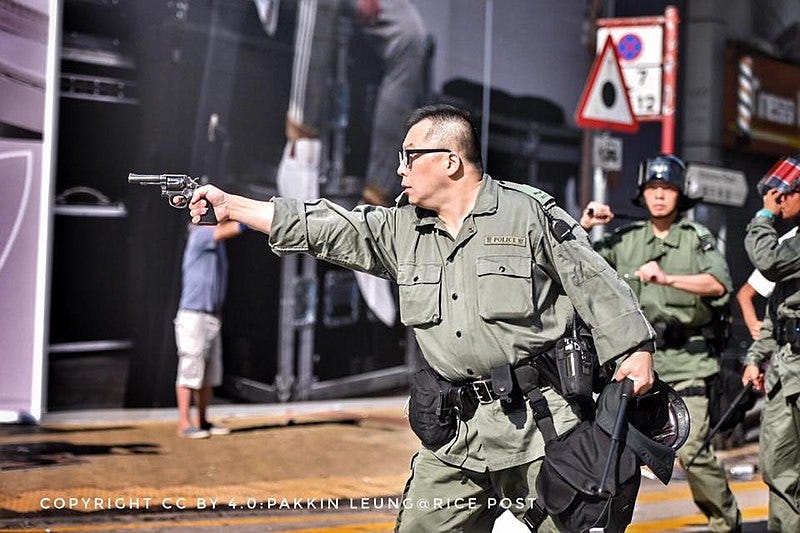

30 years later, the Chinese police bureaus have been trained for social stability maintenance [in order] to deal with these kinds of situations. They're more responsive, and they have more strategies [and] tactics to disperse the crowds, repress the crackdown, and prevent and deescalate the situation very quickly. The process has started already today [Monday, November 28].

Jordan Schneider: I think you're right. My sense is over the weekend, the police system was caught a little bit off-guard. What you're seeing on Monday night China time is massive police presence that has seemingly made it hard, if not impossible, to gather like they did on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday.

Ling Li: The protest spread overnight, or over a couple of days, in so many different places, which is unseen for the last 10 or 20 years. One of the reasons that it could happen is a weakening of surveillance control, maybe because of the economic slowdown. The state does not have such a big amount of resources to hire all these workers to conduct online activity reviews and surveillance as efficiently and effectively as they did before.

Jordan Schneider: There's this narrative in the Western media that China's internet ecosystem is fully controlled by the Party, but the amount of content that got shared millions of times on WeChat, Douyin, Douban, Weibo, and whatnot was truly astounding to see over the past few days. If you're not going to take more extreme measures, like shutting down WeChat Moments [or] pulling the plug on the internet, and you're still allowing people to post in real time, ultimately you are going to run into a human-capital limit on the censor side.

Do you think the online and in-person protests over the past few days caused Party leadership to question any assumptions they had?

Ling Li: There's this debate [about the extent to which] Xi Jinping is objectively informed of what's going on in his country. I think this question should be further subdivided. For example, for the Urumqi fire, I'm sure he's going to be informed that something happened and a number of people got killed in the accident.

However, would he be objectively informed of [what] caused the accident?

Is he going to be briefed as if the accident was caused because the residents there failed to behave themselves properly, as an official announcement has said? Or is it going to be explained as if the excessiveness of the lockdown measures prevented people from escaping?

The Impending Crackdown

Jordan Schneider: It's not just the information; it's also the mindset and frame. I can't imagine a world in which he sees protests on the street as something to be responded to softly or in a conciliatory manner.

Ling Li: I think the repression will have to happen. We don't know the severity of the repression yet, but [protesters] will certainly be demobilized for now to prevent the continued spread of the protest in other parts of the country.

But what are they going to do with all those leading students, especially the organizers of the protest? That's another issue. He could treat them with more leniency through education — 以说服教育为主 [“mainly through verbal persuasion as education”]. The worst case scenario is to prosecute them.

Jordan Schneider: What are the pros and cons of “let's just sweep this under the rug and not make a big deal of it”, versus “let's make an example out of some people in an aggressively public manner”?

Ling Li: I believe he will make a few exemplary cases to deter further, or similar, actions from other students, or other people who have the inclination to go to the streets and air their grievances. But I don't think it's a wise decision or a good time — it’s probably never a good time — for large-scale repression, which means [arresting] a lot of people and [sending] them through the prosecution procedure, as we have seen in Hong Kong.

It's not that I believe that Hong Kong protestors should be treated more harshly — certainly not. But I have an intuition that he might see domestic politics differently from politics in Hong Kong, which is further away. Whatever he's doing in mainland China might be multiplied. Its multiplication effect may lead to some outcomes that he does not want to see or will be more difficult to control.

Jordan Schneider: So the downside of more aggressive repression is scarier when you're talking about arresting students in Beijing, [compared to] arresting students in Hong Kong? That may be true objectively, but that may not be something that resonates in Zhongnanhai. Or maybe not? I don’t know.

Ling Li: There certainly will be hardliners, like what happened in 1989. But we don't know who belongs to which camp: especially with this newly elected Politburo and PSC, they have a lot of new members whose personalities and political stances we are yet to learn.

Challenging Assumptions About the Future of China

Jordan Schneider: There's this narrative that Chinese people are docile and have been ruled by autocracy for thousands of years, and you can't expect Chinese people to be particularly excited about civil rights. All things considered, since 1989 things have been relatively quiet on the mass political activism front. Has what you've seen over the past few days caused you to question any of your assumptions or challenge stereotypes? How much should folks update on the potential future of China given what we've seen over the past few days?

Ling Li: If you think rationally, the strength between the protestors and the government that you are protesting against is disproportionate.

You are on the losing side, and that's clear to everyone. It's a high-risk and no-gain activity.

But emotion is contagious. When you see a larger crowd of people who go to the street, you may be affected by it very quickly without having to process rationally. That's why a critical crisis may trigger this emotion: in the right environment where information can transmit more freely, something like this might happen. If the Urumqi fire is the trigger, and the relaxed surveillance measures on the internet and long-time repression by the government because of the lockdown policy for the past three years will be the catalyst. Add it together for the perfect storm, which is what we saw yesterday.

Jordan Schneider: It's such a deep irony: the “greatest” manifestation of the CCP in controlling the spread, when almost every other country in the world couldn't, was because the Party is so close to people and has the ability to control down to very local levels and manifest state power in such an in-your-face way.

One could argue that being able to stop the spread without having millions of Chinese die was the greatest triumph of Xi in 2020, but [it] also directly led to the greatest challenge to power that he's seen.

Ling Li: We live in our own echo chambers. But there's also a considerable percentage of the population in China who do not support the protests for whatever reason. There's also a segment of society in privileged neighborhoods who have not suffered that much from lockdown measures. Certain sectors of the population even benefit from the lockdown measures, and they do not share the same level of sympathy with the protestors as many others do.

What Next for Zero Covid?

Jordan Schneider: How do you think the protests will impact the trajectory of Covid Zero?

Ling Li: Students and people are making speeches and articulating why they are doing what they are doing. It's very difficult for Xi to claim that he didn't get the right message. That information should be able to flow to the top decision-maker without much distortion.

If that is the case, I think he has to take it into consideration. Because they have already relaxed the lockdown policy at the beginning of November, that shows there's a certain flexibility among the top decision makers in the new PSC to start to prepare the population for the easing-up.

What they need to do very quickly is to reallocate the resources to the direction of vaccination and building up capacities in public hospitals, instead of pouring all the resources into lockdown measures.

Jordan Schneider: Is there anything we can say now about what, if anything, these protests do for China's relations with, and standing in, the world? I think a lot of countries are basing their relationship with China on the expectation that China is going to inevitably grow stronger, bigger, richer, and more powerful. Maybe one thesis is that as China's growth is slowing and societal fissures [emerge], China doesn't seem quite as scary anymore if you're sitting in Delhi or Tokyo.

There's also a timeline where domestic disturbances become so overwhelming that Xi decides that he wants to escalate something in Taiwan as a way to distract folks, or another border potentially. This is very aggressive, irresponsible speculation on my part, but I do think these sorts of things resonate globally in one way or another. Another way this could play out is if you do see an aggressive crackdown, European countries who are still on the fence about just how they want to chart out their relationship with China going forward might ask some harder questions.

Ling Li: It certainly will impact foreign relations between China and the rest of the world, depending on what the party is going to do. I don't think the German government or industries will change their strategies with China because of the protest, but it will have an impact depending on what the Party is going to do afterwards. If there's massive repression, like what happened in ‘89, that certainly is not going to be conducive to a conciliatory approach between China and the rest of the world in foreign relations.

The party has a choice to make and it will be a very difficult one. On the one hand, you have to play tough in front of the challenges. Otherwise, it would set a bad example: it will induce more protests in the future, which is something the Party does not want. But if you play tough, then it has its consequences as well, directly and indirectly.

It's a pity that we’ve come to this point because it [didn’t] have to be this way. I'm no medical expert, but I have been told over and over again that winter is a good time for the virus, but a bad time for easing up.

If they had done something last summer, probably the most critical moment of the crisis would have been over by now.

If they had started importing mRNA vaccines [then], they would have vaccinated the more vulnerable population for one dose at least by now.

Jordan Schneider: They absolutely did have choices and different leadership could have made different decisions, particularly over the course of late 2021 and 2022.

How Protests Caught Everyone by Surprise

Ling Li: I was surprised by how quickly the protests spread, because when you have been observing the whole situation for three years, you would have thought that society is dead and nothing would ever happen. Suddenly, without any signaling or alarm, things happen.

I have more questions than answers. For example, how did the students organize? Protests in Hong Kong and other places were decentralized — there's no central leadership figure of the movement — but you have to have someone to decide where to meet, when, and what slogans we’re going to have, right? How did they achieve that, and how come the police did not capture that information before? Before the pandemic, the Party had been so successful in social control because they could detect problems before problems escalated into large-scale protest. It seems the police sometimes know more about the gathering than the people who are organizing the gathering, so that [protesters] can be blocked at home and prevented from taking public transport. This time, it seems the police were totally [caught] off guard. How did that happen? Through what platform did the students organize?

Jordan Schneider: Clearly, this isn't Martin Luther King running around slowly building up a movement church by church in the fifties and sixties. But these kids today in China have the internet. There's enough communication that has been able to happen on WeChat and other platforms that even if you don't have Telegram or Signal, you're able to really make your voice heard.

You mobilize people who are all very frustrated by just walking around the dorms and saying, “Hey, let's meet here now.” Virality on the internet, overwhelming the sensors, definitely helped bring more people to actions that started in Shanghai, Beijing, and other cities across the country. But is this something that can possibly be sustained once you get past that initial phase of surprise by the government, and the security state really ramps up? The tools available to the mainland China police state are far different from what you see in pretty much every other country in the world that has tried to repress protest, which is ultimately why I'm pretty skeptical of the idea that this is going to metastasize and sustain in the way a protest in Iran or Hong Kong did. But there's an outside chance that I'm wrong and this leads us into a very dangerous place.

Ling Li: Yes, I totally agree. There's one thing I want to add: millennials grew up in an environment where they watched American talk shows, American television, and Hollywood films. On the one hand, they continued to receive brainwashing political education from school. But the naughty in the classroom received different kinds of entertainment and information, which are heavily influenced by the Western world. That, probably, has also contributed to a different value system compared to the older generation.

One last thing I want to talk about is the legal development over the last 20 or 30 years. There are still significant problems [with] restrictions on judicial independence, judicial autonomy, and the autonomy of the legislature, so it's still very difficult to challenge governmental actions in China, let alone the Party. However, legal education in the last 20 or 30 years has injected a common awareness of rights and limitations of power.

[In] so many videos that have been leaked out from China, normal residents try to make a legal argument [against] police who are trying to enforce lockdown barriers by asking them, “What's your source of authority? Do you have a written document that gives you the power to lock our doors?”

In many instances, they succeeded.

Outro music is a clip of a car playing “Do You Hear the People Sing” from Les Misérables in Hangzhou, near a site where a protest was allegedly planned but quashed by heavy police presence. As the song plays, an announcement in the background drones, “Do not loiter, do not gather, do not loiter, do not gather…”