China Talk, June 4, 2024

Making war is difficult, yet making peace is not easy 战难和亦不易

Nicholas Welch: Even if all the constraints and restraints have basically disappeared, what hasn’t changed is how insanely difficult it is to pull off the invasion.

Tanks don't walk on water. Boats aren’t hypersonic. The Taiwan Strait hasn’t gotten any narrower. Taiwan hasn’t built more landing beaches for the PLA.

The longer Xi stays in power, the more different Taiwan becomes and the harder it gets to swallow. Just like Mao said, Taiwan is not desirable.

Peter Harris: While it’s true that the geography has not changed, China is more capable than they were twenty years ago, and the costs of restraint have changed. The more American leaders talk about Taiwan as this democratic outpost that is essential to the defense of the Indo-Pacific, a critical node in America, the more the costs of restraint increase.

“Oh gosh, the Americans, they’ve changed the way they think about Taiwan. Even though it’s not becoming any easier to seize Taiwan by force, it’s become more important to pull the trigger ASAP — because if we don’t, we’re going to wake up in five to ten years’ time and the US will have recognized an independent Taiwan and brought it back under its security umbrella.”

— The CCP, maybe

Jared McKinney: The truth is that an invasion would be incredibly hard — and we actually have good evidence for why.

|

But this difficulty can be made even harder with relative ease. That’s where we would disagree with Brands and Beckley.

We’ve read articles recently saying we need to spend 5% of our GDP on defense to get ready for this challenge. We’ve read an article saying we need to threaten a preemptive nuclear war against China if they suggest they’re going to invade Taiwan.

We disagree with all of that. We think deterrence can be restored much more easily.

One of my brilliant army students [coming soon to ChinaTalk!] did a year-long investigation of America’s plan to invade Japanese-occupied Formosa in 1944. This was known as Operation Causeway.

At the time, the US calculated that we needed 3:1 force ratios to successfully take the island. There were 98,000 Japanese soldiers on the island, which meant that we needed close to 300,000 soldiers to land on Formosa in order to defeat the Japanese.

Today, there are 169,000 soldiers in Taiwan’s military. There’s also the potential for reserves, but their quality is unknown, so we’ll stick with 169,000 as our estimate.

If you do similar force ratios today, we’re talking about half a million PLA soldiers on the island. Given the PLA’s lift capacity including civilian assets like ROROs, achieving that number of boots on the ground requires moving 50,000 troops onto the island per day. The truth is, in war, many of those are going to be killed, and you’re not going to be able to land soldiers that quickly.

We chose not to invade Formosa because the costs of such an invasion were too high. We think that objective assessment of similar variables today shouldlead to the same conclusion by the CCP. However, we’re not in the minds of Chinese decision-makers, and we don’t know how they weigh different variables.

Now, how do we make an invasion harder? We should learn the very obvious lessons of Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, and invest in twenty-first-century capabilities like drones, mobile missiles, and artillery. Older technologies like mines will need to be deployed en masse.

Taiwan has more than a million people who’ve done their conscript duty — they are in a theoretical reserve. If you can turn the theoretical reserve into a real reserve, then a successful invasion actually becomes impossible, because if you take 1.5 million reserve soldiers plus almost 200,000 active soldiers, then China would need to land 6 million people to be successful. That’s larger than the whole PLA.

Singapore's model is an excellent example of how this could be done. Shang-su Wu 吳尚蘇, a Taiwanese scholar, wrote a book on Singapore’s national service system, how it works, and how it could be applied in Taiwan.

That would achieve robust deterrence. It doesn’t require radically changing the status quo in the US-China relationship.

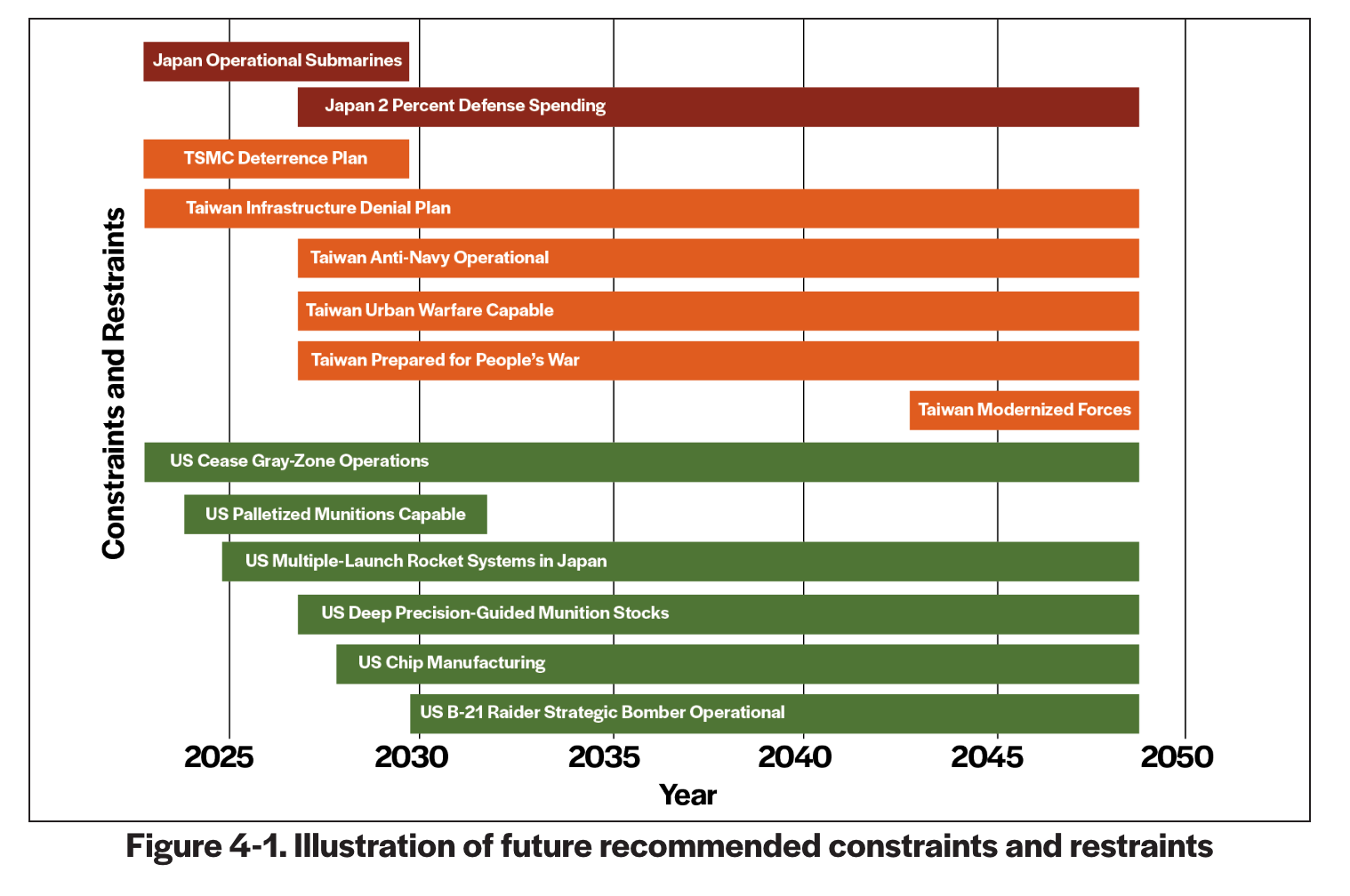

The most important takeaway in terms of military capabilities, is that we need to make sure we’re staggering them in phases. In other words, we just need to be very careful of our timelines so that there aren’t decade-long deterrence gaps. We should think of deterrence on a sort of year-by-year basis.

|

The Peak China Hypothesis and Military Modernization

Nicholas Welch: Hal Brands and Michael Beckley argued in their book Danger Zone that China’s window of opportunity is closing because their economic trajectory doesn't look super good. Thus, it’s either now or never to invade Taiwan.

Do you agree with that argument?

Jared McKinney: Yes. But there’s an important nuance with that argument related to military modernization cycles.

Beginning in the 1990s, the PRC began a long-term modernization project. It didn’t actually bear fruit until about 2014. This led many people to underestimate Chinese military power.

While this was happening, Taiwan was in its authoritarian-to-democratic transition and was refocusing on basically domestic politics. America was embroiled in its wars in the Middle East.

China completed this long-term program, and now we see that they are producing something like 100 J-20s (歼-20) per year, modernized support aircraft like KJ-500s (空警-500) and KJ-2000s, and they’ve built a very sophisticated navy with advanced air-defense systems and serious strike options. They’ve done things that even the US hasn’t done, like putting anti-ship ballistic missiles on to naval vessels, according to the DoD report to Congress in 2023.

Now, the United States and Taiwan are counter-modernizing against these capabilities. China’s cycle took about fifteen years. That’s probably how long our cycle is going to take.

Our counter-modernization programs include:

The B-21, which is supposed to be able to penetrate A2AD-defended airspace;

The Columbia-class submarine, which is going to be the greatest submarine in the world when it comes out;

New army and Marine Corps capabilities, including modeling some of China’s new capabilities.

All of these will come online around 2030.

Meanwhile, Taiwan is modernizing its military. It’s moved from four months to one year of conscription. It’s raising its military budget, and it’s looking to acquire some new capabilities that could pose a more serious threat to the PLA. All of that is going to take time as well.

The same story is happening in Japan. The Japanese self-defense force is modernizing with the goal of becoming a master counter-strike organization by 2030. That means, if Japan is struck, they will be able to respond with equivalent weapons. This is going to pose actually a very significant deterrent long term and is going to offer much better protection to forward-deployed US forces in Japan.

The problem with all of the counter-modernization activities is not that they’re happening, but they’re happening on a timeline that’s pretty far in the future.

At the same time, China is at a pretty good place in its modernization program. It’s possible that Chinese decision-makers could decide that now is better than later. We saw similar logic in Germany in 1914, which was driven by the military modernization programs of Germany’s adversaries.

They saw that the Russian army was going to be a million men by 1917. Germany plugged that data into their gonkulator and decided that they couldn’t win a two-front war against both France and Russia if Russia had an army of a million men.

Jordan Schneider: We had Michael O’Hanlon on the show about a year and a half ago. He wrote this fun paper where he tried to run some gonkulator calculations on whether the US could defeat a Chinese invasion.

War in Taiwan: Who Would Win? ChinaTalk |

My takeaway was that China would need the probability of success to be really high in order for them to act to change the status quo. Regardless of who’s got the coolest fighter jets, the biggest downside is still the multi-trillion-dollar economic losses.

I think it would be really hard for decision-makers in Beijing to talk themselves into the “three days to take Kyiv” pitfall the way that Putin did.

My sense is that the scariest thing from the PRC perspective might actually be having the war take longer than they had hoped.

Jared McKinney: I think we agree that the best solution for the PRC is to drop the talk about reunification by 2049 and go back to Deng Xiaoping’s thousand-year timeline.

But you can read the third historical resolution, and it says that they intend to reunify Taiwan. Whether they meant it or not, I am not sure. But they did say it. My suggestion would be to stop saying it.

Maybe Xi could give a speech on strategic patience and focus on the long game, like Deng.

The Risks of Accidental Escalation

Jordan Schneider: Your book, while convincing, sort of punts the awkward political logic of entanglement, which seems pretty relevant given the new developments in the dance of death between Iran and Israel.

That hasn’t led to armageddon yet, thankfully, but there are plenty of scary historical parallels.

Another scary parallel that comes to mind is the logic of Bush #2’s invasion of Iraq. The fantastic book Japan 1941 documents how no one in Japan ever made the decision to go to war with the US, but everyone in the bureaucracy sleep-walked forward into escalation anyway.

It’s awkward to be the one to dissent in a bureaucracy. Nobody wants to be the person who walks up to the theater commander and says, “This is actually a f*cking terrible idea.”

What does the escalation ladder look like if the PLA starts with something modest like a blockade? Could it potentially spiral into a situation where Beijing decision-makers feel like they are locked in and no one has any choice but to double down?

Peter Harris: The important thing to remember is that there will be crises in the Taiwan Strait. We can be pretty confident of that due to the unpredictability of domestic politics in the US, Taiwan, and China.

The question is, “How do you get to a dynamic that disincentivizes that kind of gradual autopilot escalation?” There needs to be confidence in those moments that if the CCP does de-escalate, they’re not going to bear some terrible cost by backing down.

In crisis moments, leaders fear that if they don’t seize the present moment to do something, then they’ll lose that opportunity in the future or suffer enormous future costs.

Regarding Iran and Israel — I was really concerned at one point over the past few days that Israeli leaders would respond to Iran’s strike by striking Iran’s nuclear facilities.

|

I could imagine the conversations inside the corridors of power, where some hawk says, “This is the moment. This is our only chance to retaliate against Iran’s nuclear sites. We’ll enjoy regional support, and we’ve got a good excuse or pretext because Iran just struck us. It’s a once-in-a-generation moment.”

That didn’t happen, thank goodness — but why not? War was avoided, I assume, because inside those corridors of power in Israel, they had confidence that they didn’t need to escalate to that level. They felt confident that their post-crisis survival was already assured.

You need that kind of dynamic across the Taiwan Strait. When a crisis happens, it’s important that Chinese leaders don’t feel pressure to move due to fear of losing out on the time-sensitive opportunity to peacefully unify with Taiwan.

It’s really important that the political and diplomatic foundations are robust enough to withstand those crises. We have to make clear that peaceful unification is a theoretical possibility to the future.

You need deterrence in a situation like this — your deterrents are the cap on escalation. They are the ceiling above which escalation triggers a catastrophic event. That event doesn’t necessarily need to be WWIII or the threat of a preemptive nuclear strike by the USA.

If Taiwan itself can adopt a military posture that just makes invasion prohibitively costly for the PRC, then you can combine these two pieces to see that the costs of restraint are not too serious, but the costs of war are very serious.

Face Politics, Xi Mania, and Recommended Reading

Jordan Schneider: In the book Chiang Kai-shek’s Politics of Shame, I learned that Chiang Kai-shek kept a diary for essentially his entire life. This diary had different columns to write daily updates on things like family, country, politics, exercise, what I ate, the weather … but then there’s a column called Japan and national shame. Then after fleeing to Taiwan, he starts a column on Taiwan and national shame.

I worry about dynamics like ego, manhood, and losing face 丢脸 in the One China dynamic. Everyone knows Taiwan’s been its own thing since 1949, but that’s not a fun fact for Chinese leaders to acknowledge.

Thus far, we’ve been talking about decision trees and game theory in a very rational way. But how can we analyze the risks of invasion if the decision to invade is going to be an irrational one? How can we make sure these military leaders can still sleep at night if they decide against going to war?

Jared McKinney: A lot of those issues were probably engaged with Nancy Pelosi’s vision to Taiwan in 2022. Pelosi’s visit was technically not a new incident because Speakers of the House had visited before. But when Speaker Newt Gingrich visited Taiwan, he did it in a way that actually gave face to China.

Gingrich visited the mainland first, and he met with important leaders there. Then he made a quick visit to Taiwan, he didn’t spend the night, and he didn’t talk about Taiwan versus China issues at all. He focused on positive aspects of the relationship.

On the other hand, Speaker Pelosi’s visit espoused democracy versus authoritarianism, freedom versus communism — it was very zero-sum. That’s just throwing fuel on the fire 推波助瀾 — and there is no need to take that approach.

Peter Harris: There’s at least some polling evidence that ordinary Taiwanese understand this dynamic. People in Taiwan express a little frustration or anxiety when US leaders take steps that can be perceived as incendiary or unhelpful. Everyone’s security is improved when everyone is content.

Pompeo’s idea of putting China in its proper place — there’s no way that can be construed in a constructive way. It’s just not useful discourse.

But I certainly understand there’s a danger of going too far in the other direction and being too sympathetic to the Chinese position. The United States shouldn’t rhetorically capitulate and go too far. But I agree that there’s a huge risk to trying to humiliate and to force China to kowtow 磕頭 into submission. That may well backfire.

Jordan Schneider: My recommended reading on the subject — The Consequences of Humiliation: Anger and Status in World Politics, by Joslyn Barnhart [full show on this book coming soon to ChinaTalk].

Jared McKinney: I recommend Democracy in China: The Coming Crisis, by Ci Jiwei 慈继伟. He’s a professor in Hong Kong, and wrote this book in 2019 as he watched the protests in Hong Kong unfold.

This book is a letter to the Chinese Communist Party, arguing that it’s in the interest of the party to reform and introduce democratic elements. He argues that a CCP that refuses to reform is dooming itself to a future secession crisis. He doesn’t make a moralistic argument, but rather uses logic that he hoped could persuade the party.

Nicholas Welch: Here’s a quote from that book — perhaps a one-paragraph summary of the point he’s trying to make:

[T]here is simply nowhere for the [Chinese Communist Party] to hide when the economy is not doing well or doing less well than before. This means that the Chinese party-state cannot speak of economic crises in the same way Western democratic governments can. In [the Westerners’] strict sense, economic crises are serious disturbances of a market economy conceived of as an autonomous system and, as such, presuppose a degree of separation between system integration and sociopolitical integration that is simply absent in China. For this reason, every crisis in China that otherwise resembles an economic crisis is directly a political crisis. The [Chinese Communist Party’s] role is so defined that it cannot convince anyone that “it no longer rules”— including over the economy.

Peter Harris: Individuals worry about things like shame and regret. Those emotions are part of what drives PRC leaders. They don’t want to lose a war, but they care about other things, too. They care about their political legacy. They care about national greatness. You can manipulate that or you can leverage that in service of stability and the status quo.

Jared McKinney: The reason why this is really important is because there’s a Xi-mania when it comes to understanding China.

The problem is, nobody actually knows what Xi is actually feeling in his heart. Actually, his method of ruling China is to avoid coherent guidance, because if you avoid coherent guidance, then all the decisions have to be brought to you. That means you get to micromanage things because you actually haven’t empowered people based on principled objectives.

For example, on one hand, Xi talks about increasing self-reliance. On the other hand, he talks about increasing trade. Which one is it?

The way to avoid Xi mania is to look at factors that can actually be tested. The important thing is to construct a falsifiable argument.

We suggest nine of these factors.

One such factor — are Chinese commentators optimistic or pessimistic about peaceful unification in the long term? For comparison on this metric, we look at the essay by Jiang Shigong 强世功 back in 2005. At the time, he was an optimist about Taiwan, and he actually identifies some metrics that could be used to achieve peaceful unification. Are Chinese intellectuals still optimists today?

Another measurable variable — as Chinese economic growth slows, is Chinese military growth going to slow as well? In reality, Chinese economic growth was probably close to zero last year. But the Chinese military is still growing pretty robustly, at around 7% of GDP. So it looks like so far, military growth is probably exceeding economic growth.

But that’s something we will continue to watch in the future.

Another variable — will China actually develop the capabilities needed for an invasion? People talk about 2027 a lot, but that date is mostly just tied to Xi being irritated that the PLA doesn’t actually have the sufficient amphibious lift capability to achieve a successful invasion. It seems as though he set this deadline to light a fire under the PLA. But there are other related technologies that you would need for an invasion. Are these being prioritized?

We’ve already discussed the variable of time and relative power. If we see Chinese leaders start emphasizing the idea of strategic patience, that would be a positive sign. We should watch for signs that they are starting to loosen the 2049 timeline.

It will be important to watch the results of Taiwan’s elections in 2028. In 2024, the TPP and the KMT failed to form a coalition, and that resulted in their defeat despite winning 60% of the vote. But in China’s eyes, a 60% vote against the DPP is quite a showing.

If that is replicated in 2028, that might suggest that peaceful relations could be extended further in the future.

TL;DR — there are objective variables that aren’t just trying to get inside Xi’s head, that we can try to measure one way or another to get a sense for whether we’re wrong about the urgency of the present moment.

Jordan Schneider: But Jared — wouldn’t the optimal play for Xi be to spend three years talking about patience and 1,000-year timelines, and then launch a secret surprise strike?

Jared McKinney: I mean, yes. But that’s why we need to combine rhetorical information with information about what’s happening with China's military spending or how distracted the US is in any other theater of war.

Jordan Schneider: What are your book recommendations for our readers?

Peter Harris: My first recommendation is Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley, by political sociologist John Geventas.

This is a great book for people who want to study unobservable things — which is often what you’re doing when you study deterrence. He looks at the exercise of power over people, which is invisible, right up until the moment it bubbles up and has observable implications.

This book changed the way I think about politics and the world, and it’s not even about international relations. It's about an Appalachian coal-mining town.

Jared McKinney: Yasheng Huang’s 黄亚生 new book, The Rise and Fall of the EAST, challenged a lot of my preconceived notions about China. He puts Keju 科舉 — China’s Imperial examination system — at the center of Chinese History.

He argues that the Keju allowed the Chinese state to promulgate uniformity and grow to an increasingly large scale. The super-scaled state was strong but anemic, because the exam system incentivized uniformity, disincentivized creativity, and it channeled lots of ambitious people in the same area to become bureaucrats for the government.

He argues that in periods when the examination system was more open to creativity, there was more innovation in China. But in periods in which the examination system became highly uniform and you had to write essays in a certain way, like in the Qing dynasty, China stopped inventing.

He explains that this legacy lives on today in China and the gaokao 高考 system.