Brazil’s biggest economic risk is complacency

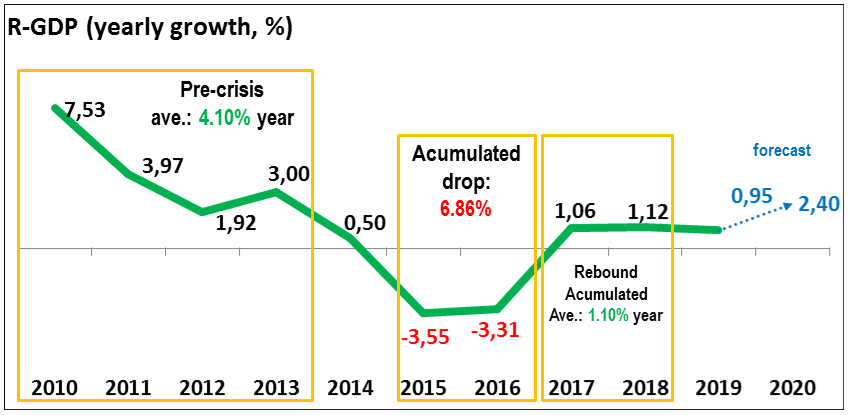

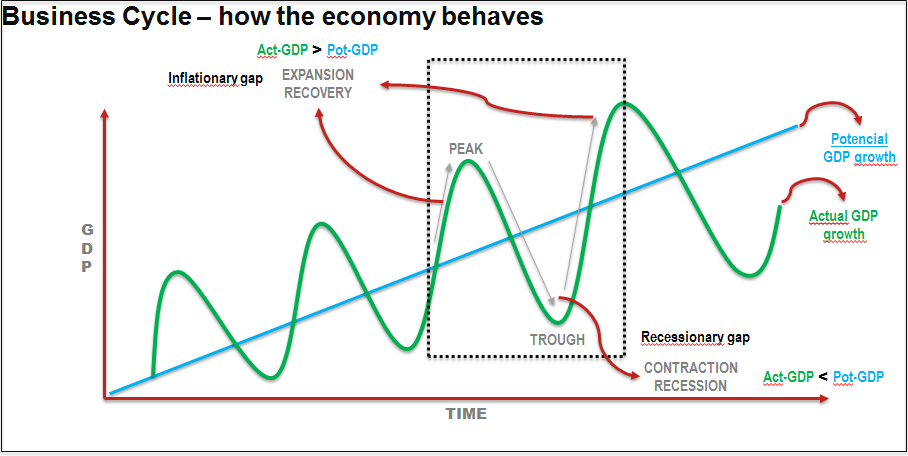

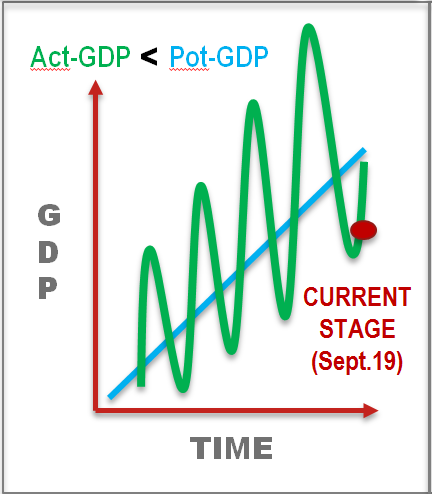

Brazil’s economy has endured a difficult few years: after a deep recession in 2015-2016, GDP grew by just over 1 percent annually in 2017-2019. But things are finally looking up, with the International Monetary Fund forecasting a 2.2-2.3 percent growth in 2020-21. The challenge now is to convert this cyclical recovery into a robust long-term expansion.

Two problems have undermined Brazil’s economic dynamism: anemic productivity and a bloated public sector. As weak productivity growth has constrained the economy’s overall growth potential, steadily rising public spending has become increasingly unsustainable.

This is not a new problem. But in the first decade of this century, it was obscured by the commodity-price super-cycle, which drove annual growth above 4 percent. In 2012-2014, pro-cyclical fiscal and (public-bank-driven) credit expansion fueled growth further, but exacerbated imbalances that would come back to haunt Brazil when the commodity boom ended.

Now, Brazil is shifting to a new economic model, in which lower-for-longer interest rates and increased private finance and investment make up for more restrained fiscal policies and reduced public-bank credit. This year could bring substantial progress in this transition, but only if the government remains committed to fiscal and structural reforms.

On the fiscal front, Brazil has already taken significant steps. In 2016, the government passed a 20-year public-spending ceiling. Last year’s pension reform is an important example of this new regimen.

But the pension reform alone is not nearly enough to restore fiscal health, not least because the associated reductions in public spending will be spread out over several years. Meanwhile, other mandatory public expenditure continues to rise.

To enable needed discretionary spending, such as on public infrastructure, all levels of government will have to curb mandatory expenditures. At the federal level, the World Bank has identified two additional areas where significant spending cuts would be possible.

First, Brazil has many subsidies and tax exemptions that bring no macroeconomic or social benefits. Second, the public-sector wage bill is high by international standards, owing not to an excessive number of employees, but to public officials’ disproportionately high salaries, relative to their private-sector counterparts.

Here, progress may be on the horizon. Last year, the government unveiled a reform package—yet to receive congressional approval—that includes sweeping changes to the terms and conditions of federal employment.

If Brazil’s government respects the public-spending cap, real interest rates (now at record lows) do not rise significantly, and annual GDP growth averages around 2 percent, the public-sector gross-debt-to-GDP ratio could decline from over 77 percent in 2018 to 66 percent in 2030. If GDP growth averages 3 percent, that ratio could fall to just 49 percent. The extent to which the government manages to make space for pro-growth discretionary spending will play an important role in determining which scenario prevails.

Financial markets offer further reason to hope that Brazil’s macroeconomic recovery will succeed. Beyond low interest rates, the country’s risk spreads have fallen to their lowest level in nearly a decade. While capital flowed out of the country in net terms in 2019, that mainly reflected the unwinding of the interest-rate premium paid on domestic debt, as well as prepayment of foreign debt by Brazilian corporates.

Meanwhile, domestic funding to Brazilian non-financial corporates has returned to pre-recession levels, and corporate-debt securities and equities have grown significantly. Capital markets have begun to compensate for the decline in subsidized credit from the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), and bank lending to businesses has picked up.

In addressing weak productivity gains, Brazil has a longer way to go. Over the last two decades, labor-force expansion has accounted for more than half of Brazil’s per capita income growth. But as Brazil’s demographic dividend ends, continued progress will require existing workers to become more productive.

Since the mid-1990s, productivity has been increasing at an average annual rate of just 0.7 percent. Inadequate physical investment has contributed to this inertia, but the main culprit has been a lack of progress in total factor productivity (TFP)—a result of poor education, weak infrastructure, and a challenging business environment.

To spur TFP growth, Brazil’s government should use concessions and privatization to convince the private sector to channel its large savings—now in search of yields—toward infrastructure. To this end, fine-tuning the regulatory framework governing private investment in areas like transport and sanitation is essential.

At the same time, the government must improve the business environment. Reforms that simplify tax administration, including by harmonizing the tax base across levels of government, are particularly urgent. Moreover, trade-opening measures and agreements—which may run up against political obstacles abroad relating to environmental and other concerns—must be pushed forward.

This year can be a decisive one for Brazil’s transition to a more robust and sustainable growth path—but only if the government commits to reform. If, instead, Brazil’s leaders simply reap the short-term benefits of improved macroeconomic performance without laying the foundations for long-term prosperity, it may not be long before the economy stalls again.