Source: Harper Collins

Journalist and historian David de Jong started work at Bloomberg just shortly after Zucotti park was violently cleared of protestors, on the orders of Mike Bloomberg, his new boss. As he describes it:

In the wake of the previous years’ financial crisis, the tension between the 1 percent and the 99 percent was palpable around the globe. Though I was hired to cover American business dynasties such as the Kochs and the Waltons (who control Walmart), I was soon asked to add the German-speaking nations to my beat …

This provides the rather striking opening to his highly readable study of ultra wealthy German families - the Quandts, the Flicks, the von Fincks, the Porsche-Piëchs and the Oetkers - and their entanglement with Hitler’s National Socialist regime.

The Nazi regime and business has been studied again and again. There were the muckraking (in the historical sense of the term) investigations that accompanied the Nuremberg trials.

Then there were the hard fought battles of the Cold War. The work of Marxisant business historians in West Germany regularly appeared with passages inked out by the order of the courts. In the US in the 1980s David Abraham, Henry Ashby Turner, Gerald Feldman et al did bloody battle over the responsibility of German business for Hitler’s rise to power. Out of that conflict emerged the first generation of new business histories led by Peter Hayes’s highly influential study of IG Farben. In the 1990s the new focus on the Holocaust and forced labour litigation triggered a further wave of studies. In some cases there were commissioned by the firms themselves. In other cases they were the work of independent academics.

There is not enough space to do justice to this huge literature in a single newsletter. I will return to it.

Though he draws on all these earlier studies, de Jong’s book is as a history of German business in the Nazi era that reflects the preoccupations of the years since 2008, the Occupy movement, and the discourse of the 1 v. 99 percent. It is, if you like, a post-Piketty history of Nazi Germany.

The families at the heart of de Jong’s book were not necessarily the most influential business people in the Nazi regime. He isn’t talking about the CEOs of IG Farben, or Rheinmetall or Krupp. His selection is dictated by two criteria - closeness to the Nazi regime in political and personal terms - and prominence and wealth in the postwar period.

The Quandt’s tick both boxes most emphatically. As owners of BMW - though that is not how their money was made - they are amongst the wealthiest people in the world. The current generation are descendants of Magda Goebbels who killed herself and all but one of her children in the Führer bunker in 1945. Magda’s first husband, Günther Quandt (1881-1954) to whom they owe their name, was a major supplier of arms, ammunition and batteries to the Nazi war effort and a gigantic employer of forced labour.

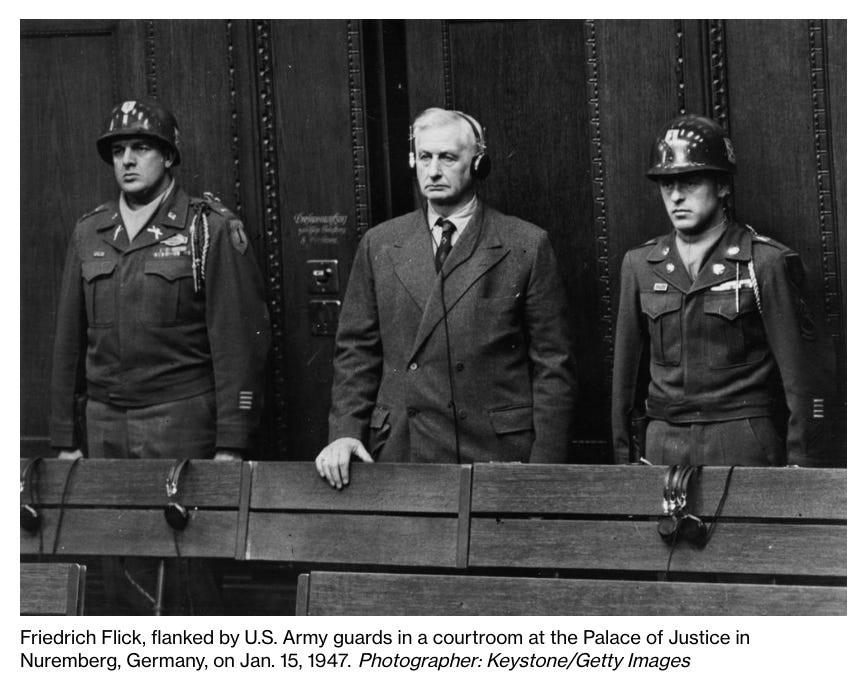

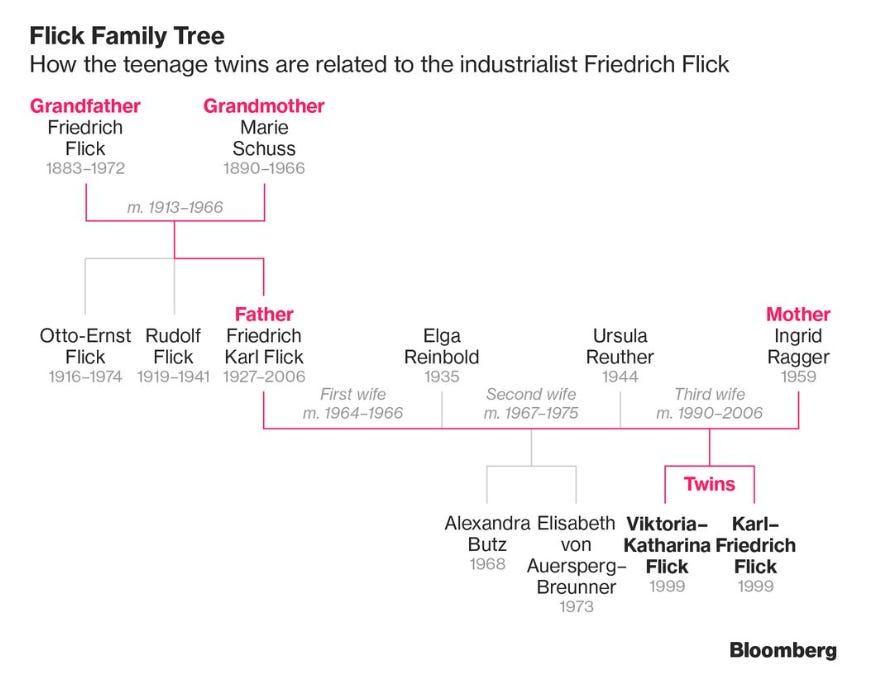

Friedrich Flick was an early sponsor of the Nazi movement and Germany’s wealthiest man twice over. His son Friedrich Karl Flick recalcitrantly denied any wrong-doing on his family’s behalf and frittered away their fortune. So that the youngest members of the family are perhaps worth a mere 1.8 billion euros each.

The von Finck family, which straddle Bavaria, Austria and Switzerland, were founders of the twin titans of Allianz Insurance and Munich Re. They supplied Hitler’s regime with an Economics Minister, helped build Hitler’s art collections and profited handsomely from the Aryanization of Rothschild assets in Vienna. Their parsimony has ensured that they have stayed in the top ranks of German billionaires down to the present day.

Rudolf-August Oetker the founder of Oetker’s dramatic postwar growth was a volunteer in the Waffen-SS officer who eagerly enrolled in training courses at Dachau concentration camp. When he died in 2014 he left his 8 children from three marriages with a brand name known throughout Germany - for baking goods - and equal shares of a fortune worth $12 billion at the time.

The Porsche-Piëchs built Hitler’s Volkswagen - a factory to rival that of Ford. As de Jong shows they not only took advantages of the Nazi seizure of power to boot out their Jewish business partner Adolf Rosenberger, but have systematically written him out of history ever since.

Though many of these stories are well known, de Jong assembles a compelling and horrifying group portrait. And his points of emphasis are thought-provoking.

Of late the literature has tended to focus on forced labour, slave labour, contacts between business and the SS. De Jong’s families were involved in that.But, tellingly, de Jong starts not in the 1940s but in 1933.

On Monday, February 20, 1933, at 6 p.m., about two dozen of Nazi Germany’s wealthiest and most influential businessmen arrived, on foot or by chauffeured car, to attend a meeting at the official residence of the Reichstag president, Hermann Göring, in the heart of Berlin’s government and business district. The attendees included Günther Quandt, a textile producer turned arms-and-battery tycoon; Friedrich Flick, a steel magnate; Baron August von Finck, a Bavarian finance mogul; Kurt Schmitt, CEO of the insurance behemoth Allianz; executives from the chemicals conglomerate IG Farben and the potash giant Wintershall; and Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, chairman-through-marriage of the Krupp steel empire.

The purpose of that meeting was not to sell big business on anti-semitism, Hitler’s plans for world conquest, or the Holocaust. Hitler’s regime as we now know it was not up for for debate. The purpose of the meeting was to raise money with which to end German democracy.

“Private enterprise cannot be maintained in the age of democracy,” the forty-three-year-old chancellor said. “It is conceivable only if the people have a sound idea of authority and personality. Everything positive, good and valuable, which has been achieved in the world in the field of economics and culture, is solely attributable to the importance of personality.”

What Hitler and his movement needed was money with which to win the election of March 5 1933. It was to be a decisive vote.

“the last election,” according to Hitler. One way or another, democracy would fall. Germany’s new chancellor intended to dissolve it entirely and replace it with a dictatorship. “Regardless of the outcome,” he warned, “there would be no retreat . . . There are only two possibilities, either to crowd back the opponent on constitutional grounds . . . or a struggle will be conducted with other weapons, which may demand greater sacrifices.” If the election didn’t bring Hitler’s party into control, a civil war between the right and the left would certainly erupt, he intimated. Hitler waxed poetic: “I hope the German people recognize the greatness of the hour. It shall decide the next ten or probably even hundred years.”

What Hitler, Goering and Schacht had in mind was a fund equivalent to $20 million in today’s money with which to win the election and end Germany democracy. They had no problem raising the funds.

The day after the meeting, February 21, 1933, thirty-five-year-old Joseph Goebbels, who led the Nazi propaganda machine from Berlin as the capital’s Gauleiter (regional leader), wrote in his diary: “Göring brings the joyful news that 3 million is available for the election. Great thing! I immediately alert the whole propaganda department. And one hour later, the machines rattle. Now we will turn on an election campaign . . . Today the work is fun. The money is there.” Goebbels had started this very diary entry the day before, describing the depressed mood at his Berlin headquarters because of the lack of funds. What a difference twenty-four hours could make.

If the choice was between consolidating Hitler’s or continuing the Weimar Republic, by 1933 the German business community knew which way it would swing.

This had not always been their choice. In the 1920s they had learned to live with the Weimar Republic and its Western-facing foreign policy. But after ten years of what they regarded as intolerable instability, with the Communist Party surging, the economy in deep crisis and little prospect of a return to the international economic order of the 1920s, they made their choice.

They were not the only ones. As I argued in Deluge, faced with the collapse of Anglo-American hegemony in the Great Depression, Italian and Japanese elites also swung to a nationalist course.

They got more than they had bargained for. German business was not without influence at the technical level in the Third Reich. In technical and industrial terms they shaped what was possible. Some who were considered untrustworthy or insufficiently enthusiastic were bullied or even lost control of their businesses. But that was far from being the majority experience. For the most part the trade offs offered by the Nazi regime were extremely attractive. There is much more to say about this but businesses profited handsomely. But any illusion they might have had that they were backing a conservative nationalist government in which figures like the publisher Alfred Hugenberg or the military high command would call the shots were soon dispelled. They had embarked on a dramatic va banque adventure dominated by Hitler’s vision of racial war.

De Jong does a skillful job of interweaving family history with the drama and violence that began in 1938 with the Anschluss of Austria and continued down to the stabilization of the 1950s.

Defeat was a shock but it did not end the prosperity of this cluster of families. All of them survived the war. Their fortunes were if not intact, then at least the basis for regrowth. And this is the bigger point to highlight about de Jong’s account. It is a story of continuity, a story of relentless accumulation across some of the most massive caesura in modern history.

To that extent it runs counter to one of the findings commonly taken away from the inequality studies of recent years, that war was one of the very few forces that disrupts entrenched wealth inequality. This is the headline, for instance, of Walter Scheidel’s The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century.

Does the emphasis on continuity in a study like de Jong’s contradict that basic idea?

Of course, one might take refuge in the fact that de Jong’s study is not an exercise in quantitative history. It is to be regretted that it does not include a quantitative tracking of the fortunes of his subjects.

By starting with the families whose wealth continued to accumulate he has built in survivorship bias. We don’t learn about the wealthy Germans - if there were any such persons - whose fortunes were destroyed by the war and the subsequent division of Germany. It was clearly bad for the landowners of East Prussia.

Focusing on the billionaires with Nazi connections gives us a distorted impression of wealth in Germany today. In the list of the top 30 German fortunes today, the Quandts and the von Fincks are flanked by families like the Herz’s who made their fortune in coffee after the war, or the Albrechts who are heirs to the Aldi retail fortune. The 2021 top 30 billionaire list for Germany is here and as far as I can see Nazi-related fortunes make up a small minority of the group.

But, survive the Quandts and the von Fincks did. And before dismissing them as flukes it is interesting to consider some other possible implications of de Jong’s history.

To start with, what do the German data tell us about the impact of World War II on wealth and income inequality in that country? What kind of shock did the Nazi regime, the war and postwar division deliver to wealth in general?

We owe the best estimates on this score to the recent work by N. H. Albers, Charlotte Bartels and Moritz Schularick in their 2020 paper The Distribution of Wealth in Germany, 1895-2018

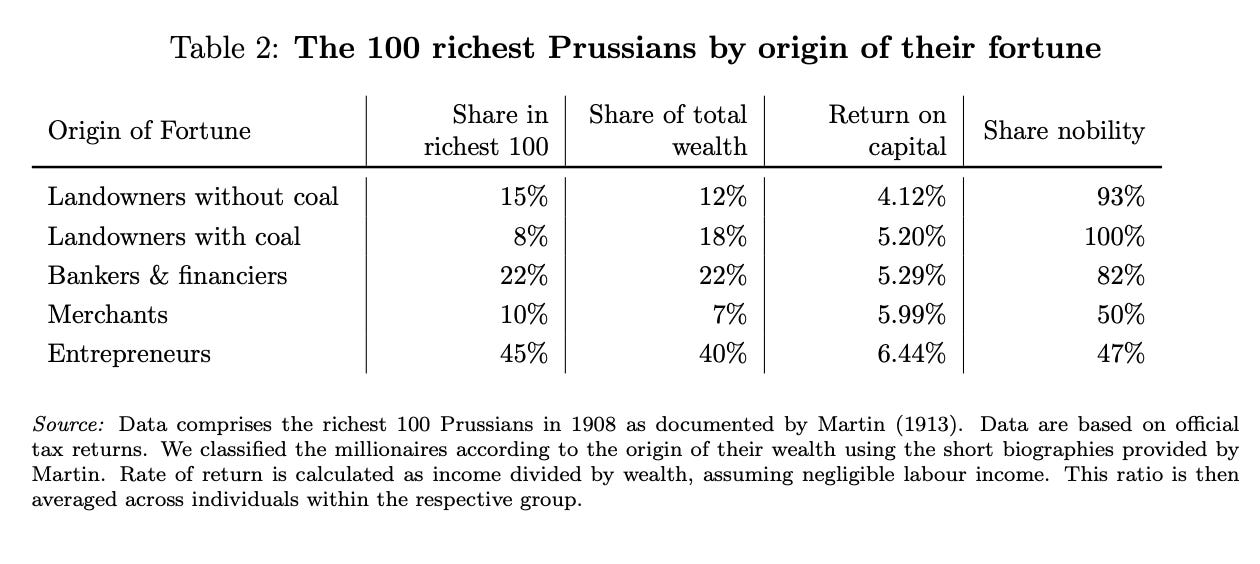

As a baseline they use Prussian data, which yield this fascinating breakdown of wealth in Prussia before World War I.

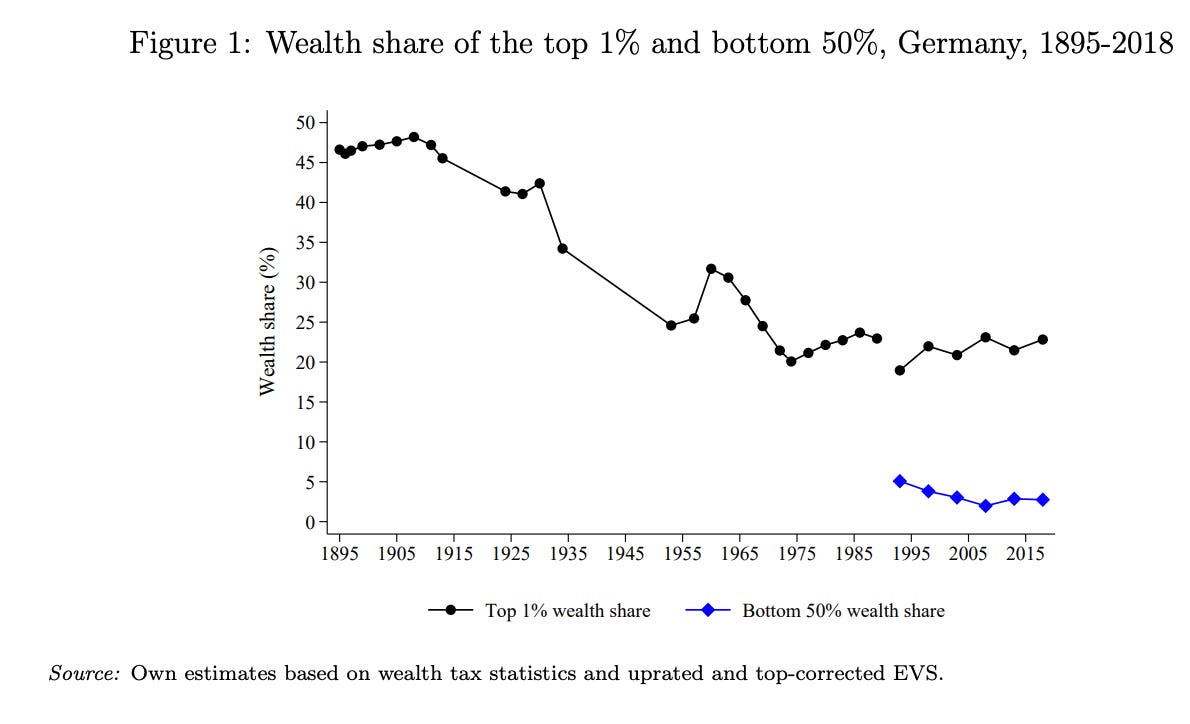

Tracking the wealth share of the top one percent shows it falling monotonously from just before World War I through to the 1970s.

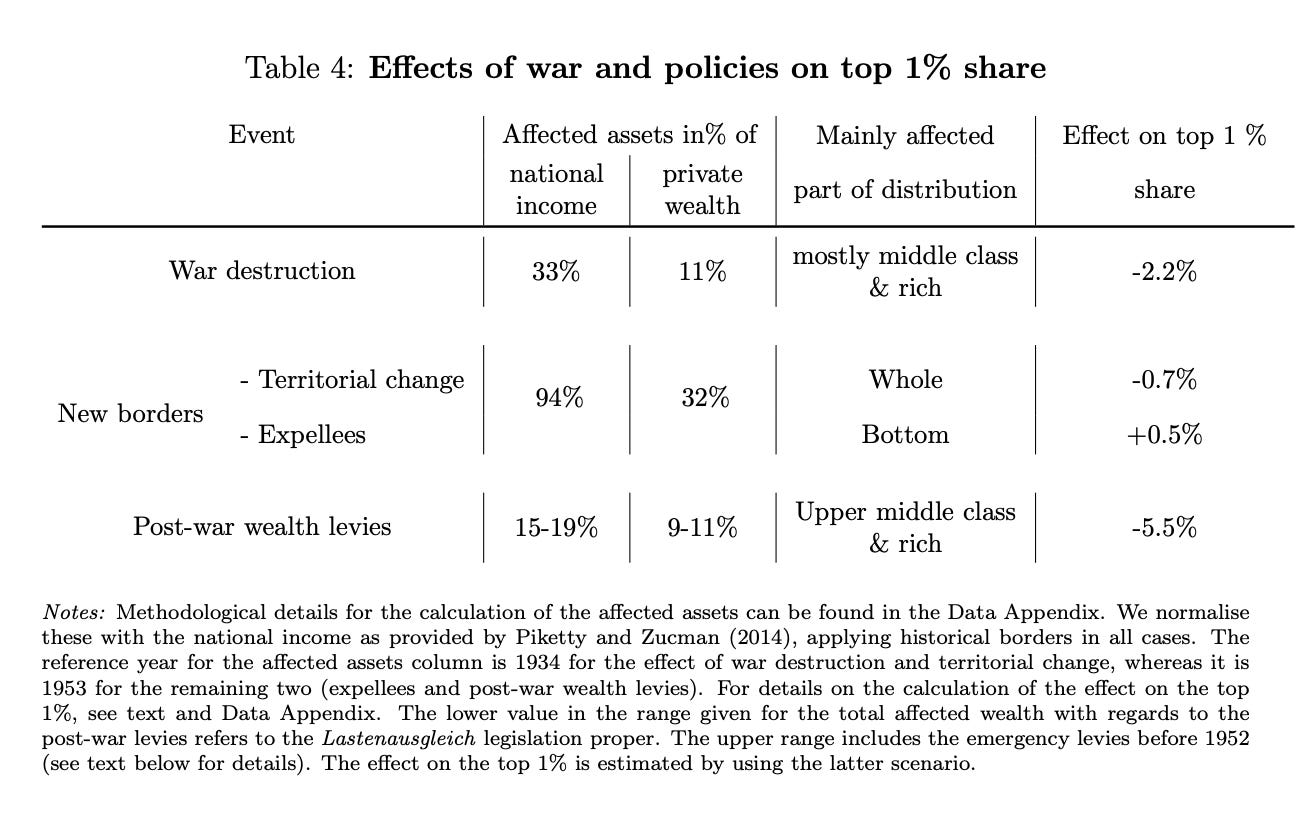

The data are patchy but what is striking is not so much the impact of the wars as such, but the Great Depression of the 1930s and postwar fiscal measures, notably the Lastenausgleich (Burden Equalization) legislation passed in West Germany in 1952, building on Weimar and Nazi-era precedents.

According to the careful estimates by Albers et al, postwar wealth taxes in West Germany had twice the impact on the top 1 % share as did the destruction of property predominantly owned by the wealthy during the war.

These are fascinating data and the postwar wealth tax legislation of West Germany are a topic to return to.

But relating these data to de Jong’s narrative still poses problems. In relying on large statistical aggregates to measure the wealth distribution are we actually able to capture the history of the largest fortunes? When we say that wars tend to redistribute wealth, whose wealth is it that gets redistributed? Is it the wealth of the ultra-ultra-rich or merely that of the very rich? The 0.0001% or the 1%? It would be fascinating to know whether the records of the Lastenausgleich tax allow one to throw light on these questions.

In the mean time there is at least one study that does dig into the top 1 percent income share.

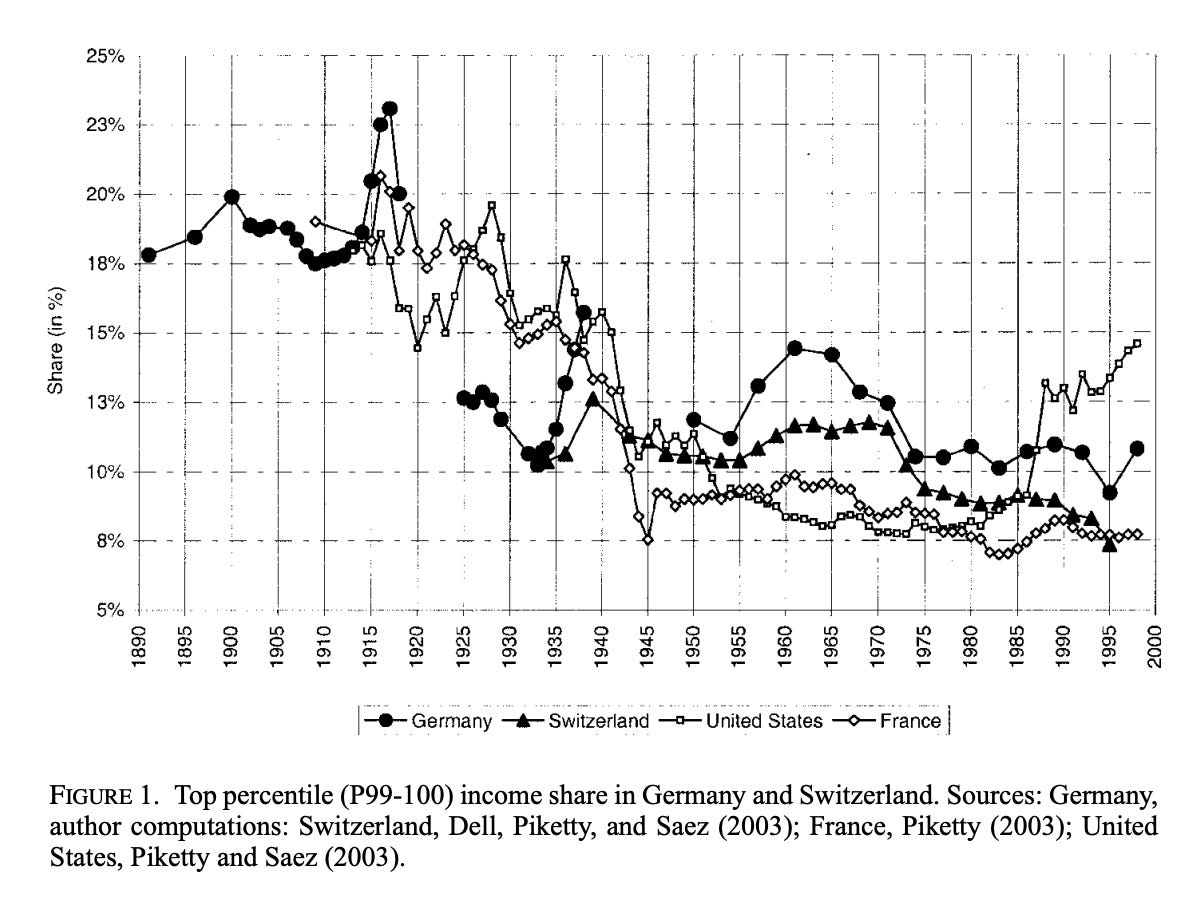

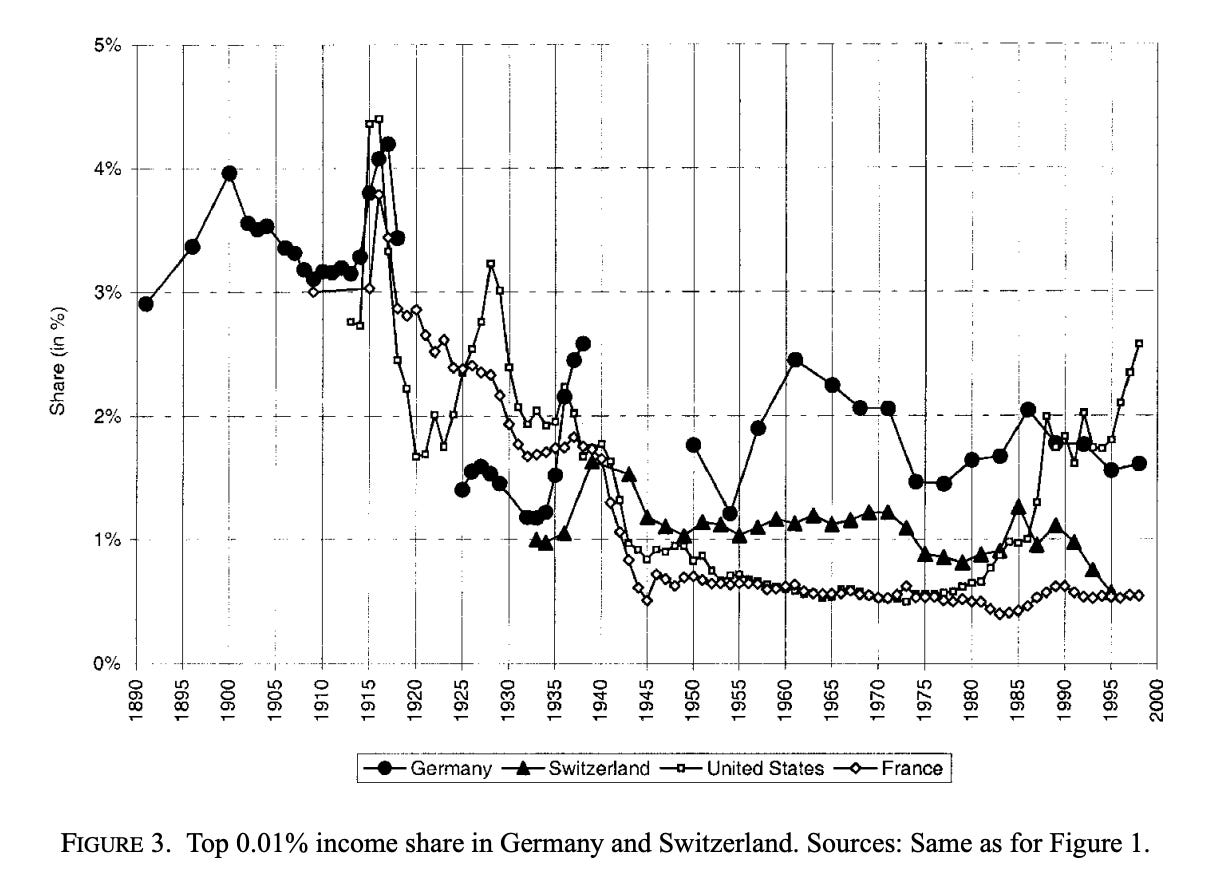

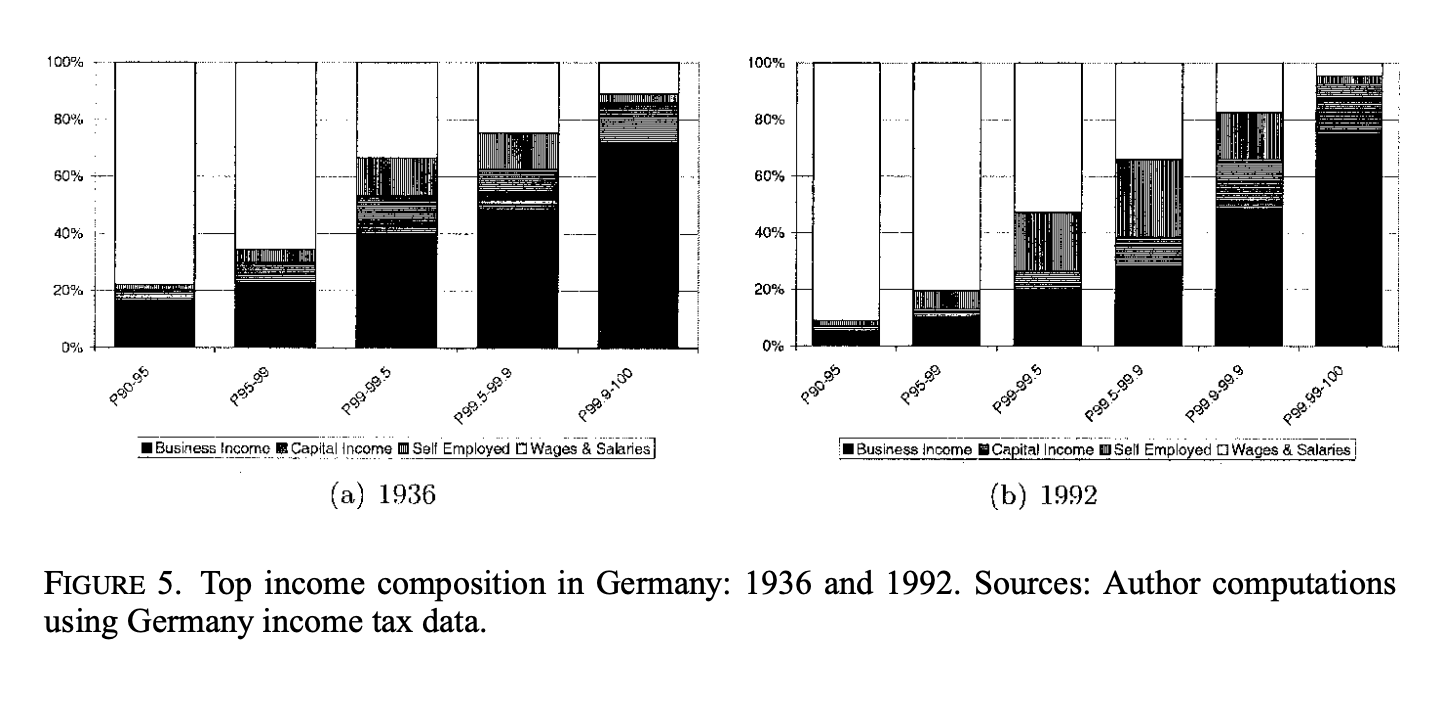

Fabien Dell of INSEE and Paris-Jourdan calculates top 1 percent and top 0.01 percent shares for German and Swiss incomes.

The income data broadly follow the story of declining inequality shown by the wealth data. But in the income data we see a major recovery of the share of the top 1 percent during the period of the Nazi regime between 1933 and 1940.

And this is even more pronounced in the data for the top 0.01 percent. Their share doubles between the Weimar Republic and the outbreak of World War II. And what is also striking is how robust the top 0.01 share of national income remains after 1945. In 2000, on Dell’s data, it is still comfortably above the levels measured for the Weimar Republic.

Income and wealth inequality are two different things. But as Dell points out, the incomes of those in the top 1 percent are heavily driven by capital income. So his data strongly confirm the supposition that the Nazi regime was very good for Germany’s wealthy class.

On closer inspection, in short, the appearance of contradiction between the aggregative view of inequality trends and the importance of war shocks and de Jong’s case study approach dissolves. Indeed, the two views seem to complement each other.

World War I, the revolution, hyperinflation, Weimar democracy and the great depression delivered a nasty shock to German wealth, which shows up clearly in a break in the income and wealth inequality data. To guard against any further erosion at the hands of democracy, the wealthy placed a bet on Hitler and between 1933 and 1940 Hitler’s regime delivered handsomely on the bargain. War damage was severe, but not devastating. There was plenty of opportunity for plunder in the occupied territories and, in the event that Germany had won, the most prominent collaborators of the regime would not doubt have been rewarded even more amply. It was a high risk gamble but not an unfathomable one. I explore the politics of the moment of maximum risk in 1939-1940 at length in Wages of Destruction. Defeat was a shock, but not, in the end, a disaster. West Germany delivered capitalist democratic stability anchored safely within the US orbit. That was a deal that German elites had been willing to accept in the 1920s under far more precarious circumstances. The price of postwar stability was some redistribution to stabilize a society crowded with refugees, homeless and displaced persons. That shifted wealth shares. But what might have been a dramatic moment for wholesale redistribution by way of a 50 percent flat rate levy on all wealth assessed in 1948, was instead commuted into a manageable tax. As Albers et al put it succinctly:

Instead of paying the full amount in 1952 (due in Lastenausgleich tax), households and companies (that had done well out of the war) made quarterly amortization payments including interest until 1979. The combined annual payment amounted to 4-6% of the total initial amount of 1948, depending on the asset type (Albers, 1989, p. 288). Put differently, the main levy thus corresponded to an annual wealth tax of 2-3% on the initially assessed net wealth in 1948. This implied that it could be paid from the returns of private wealth rather than its substance

This confirms the most fundamental point conveyed by in-depth narratives like de Jong’s. Continuity achieved by all means necessary.

De Jong alerts us to the structures of ownership and influence which perdure even if the book value of assets is written down, a family member or two falls out of favor for a while, or business is bad for a few years. Wealth and privilege persist - or perhaps we should better say they are produced and reproduced - through their anchoring in law and through networks of social contacts and relationships of trust and kinship.

They also persist through crafting self-protective narratives that legitimize and defend wealth. This is where history and, in particular, business histories come in. It can serve as legitimizing device for wealth, or as a powerful check and source of accountability.

De Jong’s book, as much as anything, is an intervention in the discourses that surround modern German wealth and its history. As he himself acknowledges it is not the most scholarly or archival study of German business and the Nazi regime. There are plenty of those, nowadays even commissioned by the businesses themselves, for the sake of transparency, of course. But, they remain untranslated and veiled in scholarly apparatus. They tend non-accidentally to disappear from view. The result is a culture of apparent transparency but de facto ignorance or even denial.

The challenge as de Jong reminds us is to reactualize this history. To continually find new ways to bring it into the present. The result is a fresh and highly readable account. But for me it is less the novel framing of de Jong’s story that I admire than the fact that he has taken up this Sisyphean labour of rolling the heavy boulder of history up the hill again.