George Orwell escreveu 1984, em 1948, contemplando o mundo terrível do stalinismo, então em pleno triunfo paranoico (tanto que Stalin inventou um "complô de médicos judeus" para assiná-lo, apenas para continuar fazendo o que mais fez na vida: eliminar supostos adversários).

Parece que o mundo de "1984" não terminou em 1989, como otimisticamente proclamou Timothy Gartob Ash, ao constatar o fim da era soviética.

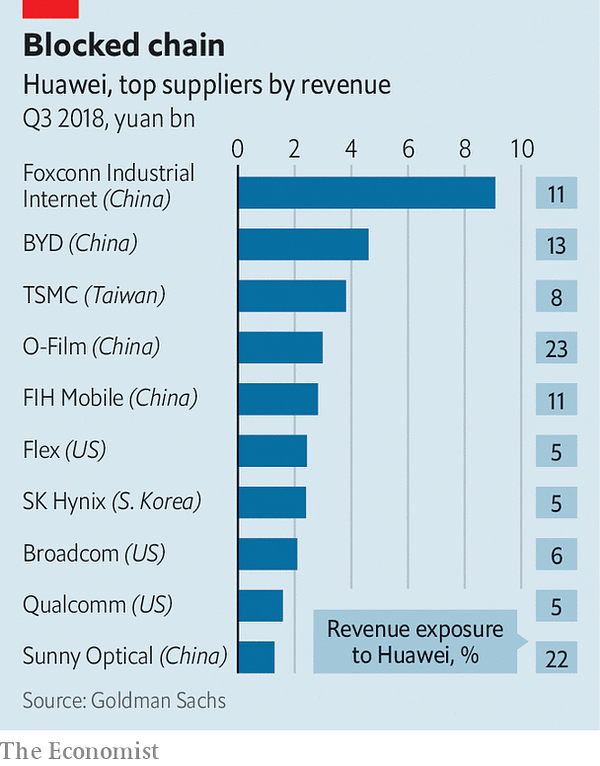

A China reproduz alguns dos piores traços do Ministério da Verdade, com sua dominação totalitária sobre a vida dos cidadãos chineses (e agora apontando em Hong Kong).

Líderes totalitários, espíritos autoritários, não conseguem conviver com a liberdade de pensamento e de expressão.

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

How the world of ‘1984’ haunts our present

Wendy Smith

The Washington Post, June 21

(Doubleday)

(Doubleday)

“The World of Nineteen Eighty-Four ended in 1989,” historian Timothy Garton-Ash declared optimistically in 2001. Communism, fascism and European imperialism “were all either dead or mortally weakened. Forty years after his own painful and early death, Orwell had won.”

If only. Orwell’s portrait of a world in which the truth is irrelevant and the powerful rewrite the past is, regrettably, not at all out of date. “I hesitate to say that Nineteen Eighty-Four is more relevant than ever,” British journalist Dorian Lynskey writes in his alarming exegesis of the novel’s significance and enduring impact, “but it’s a damn sight more relevant than it should be.” Indeed, the most powerful pages of “The Ministry of Truth” quote Orwell in the 1940s describing a state of public affairs all too familiar today.

While he was engaged in the Spanish Civil War, Orwell wrote in 1942 that he saw “history being written not in terms of what happened but of what ought to have happened according to various ‘party lines.’ ” When this occurs, he wrote, “the general uncertainty as to what is really happening makes it easier to cling to lunatic beliefs.” In a 1945 essay, he bleakly concluded about such beliefs: “To attempt to counter them with facts and statistics is useless.”

These cautionary words echo throughout Lynskey’s text. Part One explores the political and intellectual experiences that formed Orwell’s worldview. Lynskey briefly recaps his life, paying particular attention to Orwell’s six months in Spain, where he had gone to fight fascism but encountered equal ruthlessness and dishonesty in Stalin’s communists.

Orwell went home a staunch member of the anti-communist left, unalterably opposed to imperialism and fascism but committed to calling out lies on all sides. The left-wing publishers who refused to print “Homage to Catalonia” or his essays about Spain — because, they argued, the truth could be used as fascist propaganda — in his view had failed a moral test. “For Orwell, the truth mattered even, or perhaps especially, when it was inconvenient,” Lynskey writes.

“Animal Farm,” published in 1945, was Orwell’s opening fictional salvo in his battle for inconvenient truths, an allegory that suggests how the tyrannical one-party state Oceania in “1984” came into being. “Animal Farm” also marked the beginning of Orwell’s appropriation by conservatives, whom he was forced to keep reminding that he was a socialist. “1984” moved beyond satire of the Soviet Union to make a broader, more unsettling point.

In his outline for the novel, Orwell described the mood he wanted to create as, “the nightmare feeling caused by the disappearance of objective truth.” Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were pioneers in this sort of campaign against reality, but Lynskey argues persuasively that Orwell knew that they would not lack successors. “Totalitarianism, if not fought against, could triumph anywhere,” Orwell wrote shortly after “1984” was published in 1949.

He died less than a year later, leaving his most famous book to be interpreted by others. Part Two of “The Ministry of Truth” addresses “the political and cultural life of Nineteen Eighty-Four” since Orwell’s death, in scattershot fashion. The problem isn’t Lynskey’s judgments, which are generally sound, but the rambling way he develops them and the odd tangents he wanders into. A generally capable, if abbreviated, account of the novel’s influence in the 1950s, when it was narrowly seen as a warning against Soviet-style totalitarianism, contains a detour into “Orwell’s genius for snappy neologisms” and a belated, strained defense of the list of Soviet sympathizers Orwell gave to the British government’s controversial Information Research Department in 1949.

Lynskey leaps from the Cold War to “1984” in the 1970s, which muddies some interesting analysis of Orwell’s reclamation by the left with a bewilderingly excessive amount of material about “Diamond Dogs.” David Bowie’s album may include material from an aborted opera of “1984,” but it doesn’t deserve more space than Terry Gilliam’s neo-Orwellian masterpiece “Brazil” or Margaret Atwood’s chilling feminist variant, “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Part Two is a mess; it reads like a magazine article that grew but never matured into a coherent overview of the shifting ramifications of Orwell’s most famous novel.

Lynskey redeems himself in his final chapter, “Oceania 2.0.” He builds on his central focus throughout the text — Orwell’s forecast of a world where objective truth does not exist — to paint a portrait of the “toxic cocktail of cynicism and credulity” with which too many people today dismiss what they don’t want to hear as “fake news” and embrace “alternative facts” that buttress their convictions. We can’t blame Russian trolls for the 2016 election, he comments grimly: The “architects of dezinformatsiya found that they were pushing at an open door.”

Despite its faults, Lynskey’s jeremiad remains valuable and terrifying for the blistering spotlight it shines on Orwell’s overriding purpose, defined in its title, “The Ministry of Truth.” It closes, ringing and goading, with Orwell’s exhortation when asked what moral should be drawn from “1984”: “Don’t let it happen. It depends on you.”

Wendy Smith is the author of “Real Life Drama: The Group Theatre and America, 1931-1940.”