On January 22, 2021, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons entered into force with 69 state parties. The treaty aims to ban nuclear weapons, bringing global nuclear weapons arsenals down to zero. Treaty states, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, and other global zero activists that pushed for the treaty frequently highlight the existential harms from nuclear weapons, including in the second meeting of state parties to the treaty. The concern is legitimate. A 2022 study in Nature estimated a nuclear war between the United States and Russia would blast massive amounts of soot into the atmosphere, disrupting the global climate, and causing massive food shortages that could kill over five billion people.

But nuclear weapons are not the only threat to humanity. An asteroid over 1 kilometer in diameter striking the Earth, genetically engineered biological weapons, super volcanoes, extreme climate change, nanotechnology, and artificial superintelligence all could generate existential harm, whether defined as the collapse of human civilization or literal human extinction. To address those challenges, humanity needs global cooperation to align policies, pool resources, maintain globally critical supply chains, build useful technologies, and prevent the development of harmful technologies. Nuclear deterrence—alongside robust international organizations, laws, norms, alliances, and economic dependencies—helps make that happen.

Global governments and organizations aiming to reduce existential risks should support nuclear risk-reduction measures but oppose quick, complete abolition of nuclear weapons. Nuclear abolition creates serious risk of returning to an era of great power conflict, which could drastically increase existential risk. A global war between China, Russia, the United States and their respective allies risks the survival of the global cooperative system necessary to combat other existential threats, while threatening infrastructure necessary for risk mitigation measures and accelerating other existential risk scenarios. As Iskander Rehman wrote in his recent in-depth study of great power war: “Protracted great power wars are immensely destructive, whole-of-society affairs, the effects of which typically extend well beyond their point of origin, spilling across multiple regions and siphoning huge amounts of personnel, materiel and resources… Ultimately, protracted great-power wars usually only end when an adversary faces total annihilation, or collapses under the weight of its own exhaustion.” If the great powers collapse, the global system may collapse with them. Nuclear deterrence can help prevent that.

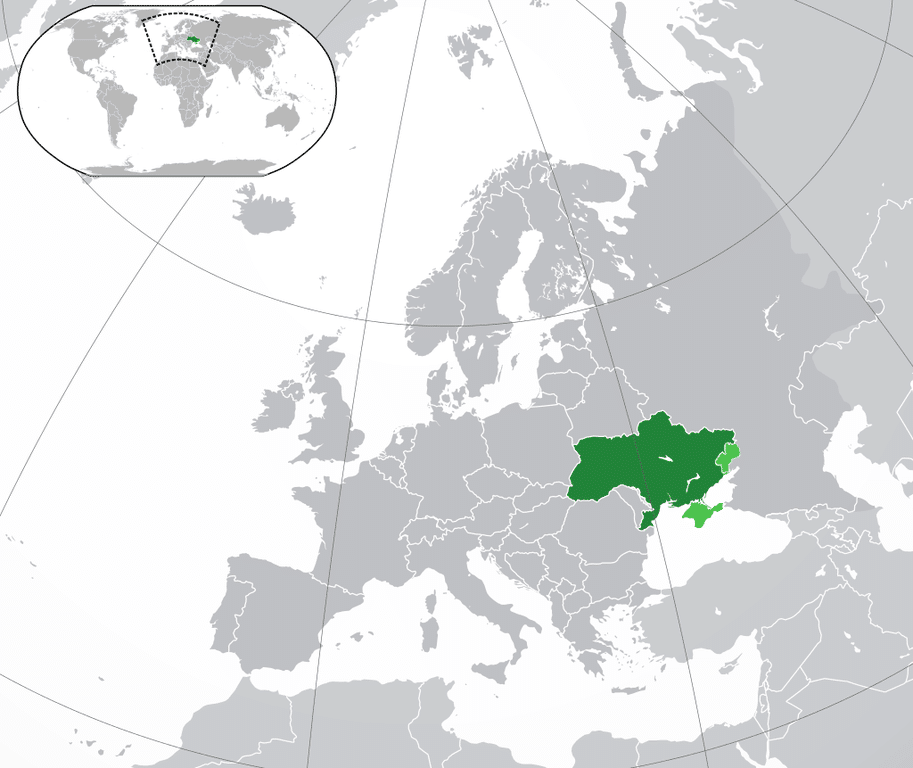

Nuclear weapons place a cap on how bad great power conflict can become and may deter the emergence and escalation of great power war. If China, the United States, or Russia faced a genuine existential threat, the nuclear weapons would emerge, threatening nuclear retaliation. As Chinese General Fu Quanyou, head of the People Liberation’s Army General Staff until 2002, once said: “The U.S. and Soviet superpowers both had strong nuclear capabilities able to destroy one another a number of times, so they did not dare to clash with each other directly, war capabilities above a certain point change into war-limiting capabilities.” Mutually assured destruction also helps prevent serious great power conflict from breaking out in the first place. During the current war between Ukraine and Russia, Russian President Vladimir Putin has used nuclear threats to deter direct NATO involvement and keep the conflict local. The United States might wish to support Ukraine against Russia, but it’s not willing to risk a Russian nuclear strike on New York City or Washington, DC to do more than provide money and material. Removing that deterrence by banning nuclear weapons means a potential return to protracted, global great power war.

To emphasize: Opposing quick, complete abolition does not mean opposing reduction of nuclear arsenals or risk reduction measures like improved crisis management and ensuring human control over nuclear weapons. Massive nuclear war is the most likely scenario for existential harm to humanity in the near term. As the Chinese nuclear arsenal grows, and China potentially aims for nuclear parity with the United States in the coming decades, that problem is going to get worse. Current nuclear weapon strategies depend on targeting adversary nuclear weapons, which means as an adversary builds more nuclear weapons, the United States must build more too. If the United States builds more, so too will Russia and China. Unchecked, nuclear arsenal sizes could quickly spiral upwards, passing the heights of the Cold War when the United States had 23,000 nuclear weapons and the Soviet Union had 39,000.

The risks of great power war. War among great powers increases existential risk in at least four ways. First, the global cooperative system necessary to combat existential threats may be seriously damaged or destroyed. Second, combatants might target and destroy infrastructure and capacity necessary to implement existential risk mitigation measures. Third, military necessity may accelerate the development of technologies like artificial intelligence that create new existential risks. Fourth, a great power war following nuclear abolition could touch off rapid, unstable nuclear rearmament and proliferation.

After World War II, the United Nations, NATO, the International Monetary Fund, the International Atomic Energy Agency, and numerous other international organizations were built to stabilize the world and prevent such a global catastrophe from happening again. That cooperative framework allowed for the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, enabled global partnerships on biosecurity through the G-7, and facilitated high-level discussions on the risks of artificial intelligence. However, a massive global war would undermine the very foundations of this order, because it would show the economic, political, and institutional ties between nations were never enough to prevent global conflict. Plus, World War III might result in the crippling or destruction of the powerful states and institutions that hold up global governance: China, France, Russia, the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, NATO, and others. The global community may lose the cooperative institutions necessary for climate change reduction, limiting or controlling risky biological research, prevent the creation and proliferation of artificial superintelligence, and generally defend the planet.

Great power war could accelerate a broad range of technologies that generate new and increase other existential risks. Russian President Putin noted in 2017 that, “[w]hoever becomes the leader in [artificial intelligence] will become the ruler of the world.” A great power war would almost certainly accelerate research, development, and implementation of artificial intelligence. One can easily imagine a Manhattan Project for artificial superintelligence, bringing together NATO’s leading artificial intelligence researchers and organizations to create a superintelligence (or close enough to it) to defend friendly cybernetworks and attack adversarial ones, manipulate adversary decision-making, or create and manage insurgent forces. Although quantum computing is not an existential risk, accelerating development to help break adversary encryption or other military purposes would exacerbate artificial intelligence-related risks, too. Quantum computing offers potentially millions of times more computing power than classical computers, and computing power is a critical resource necessary to train artificial intelligence models. Great power war might also spur massive investment in biotechnologies like genetic engineering to enhance soldier effectiveness. Improvements and proliferation in genetic engineering generate a range of biological warfare concerns from creating new biological warfare agents to making existing agents more harmful.

In a war for survival, infrastructure necessary to mitigate existential risks might be destroyed. Space launch capabilities constitute a prime example: On November 24, 2021, NASA launched the Double Asteroid Redirection Test from Vandenburg Space Force Base near Santa Barbara, California. If China and the United States were at war, Vandenburg Space Force Base would be a viable and desirable target for Chinese attacks. China has long recognized that the United States military depends heavily on space assets for communication, remote sensing, and position, navigation, and timing. And Vandenburg is home to the Combined Space Operations Center, the Space Force center responsible for executing “operational command and control of space forces to achieve theater and global objectives.” Damaging or destroying the base, including its space launch capabilities, could help China win the war. At the same time, damaging or destroying the base would make it harder for the United States to carry out asteroid deflection research and, depending on timing, prevent the United States from launching a planetary defense mission when an asteroid is inbound.

General loss of state capacity could also draw resources and policy attention away from existential risk mitigation. Research by, Greg Koblentz of George Mason University and King’s College London researcher Filippa Lentzos mapped 69 Biosafety Level 4 laboratories around the world. At these labs, research is conducted on the most dangerous pathogenic material, like the microorganisms that cause smallpox and Ebola. The United States and global community expends significant resources to secure those facilities: President Biden’s Fiscal Year 2023 budget provides $1.8 billion to strengthen biosecurity and biosafety. But in a World War III involving the United States and China, biosecurity may fall by the wayside. Even if the United States prevails, rebuilding Tokyo, Los Angelos, Seoul, or other major cities demolished during the fighting would command tremendous resources, and attention.

Finally, a World War III breaking out after nuclear abolition could trigger rapid, unstable nuclear rearmament and proliferation. The United States, Russia, China, and other nuclear powers would almost certainly realize that nuclear abolition was a mistake and rearm themselves. A post-abolition World War III would also likely demonstrate to many other states that nuclear weapons are necessary to defend their sovereignty. Rapid nuclear rearmament and proliferation could be highly destabilizing, with significant new risks of nuclear war, because new nuclear arsenals may not be accompanied by the necessary crisis communication, secure second-strike, and general deterrence doctrine necessary to ensure stability.

Even if nuclear abolition were achieved, the basic knowledge underlying nuclear weapons would not disappear. Even if all nuclear warheads were dismantled, weapon designs were destroyed, and enrichment facilities closed, the historical and scientific knowledge of nuclear energy and nuclear weapons would not disappear. Nuclear weapons knowledge would need to be retained even in a global zero world to support any monitoring or verification programs aimed at ensuring that a nuclear global zero stays “zero.” That knowledge could provide the seeds for rearmament. So, while nuclear abolition might reduce nuclear-related existential risks in the short-term, abolition might counterintuitively increase nuclear existential risk in the long-term.

Navigating the zone of uncertainty. Effectively managing the existential benefits and risks of nuclear weapons requires two questions to be addressed. First, how many nuclear weapons are minimally necessary to deter great power conflict? Second: At what point does a nuclear war go from just a moral horror and catastrophic loss of life to truly existential harm? Unfortunately, neither answer is clear and requires significantly more modeling and analysis than has been done.

Reducing nuclear arsenals only to the minimum amount necessary to deter great power war requires a nuclear state having sufficient, survivable nuclear weapons to reliably inflict unacceptable harm on an adversary. But how much harm is “unacceptable” will depend on the conflict context, leader personality, domestic and international politics, and other factors. Plus, nuclear forces might be destroyed in an initial nuclear strike; adversary air, missile, and submarine defenses might defeat delivery systems; and nuclear weapons might simply fail to cause expected harm. Finding that right balance will no doubt be hard and change over time, especially with nuclear-relevant emerging and evolving military technologies, but modeling and simulation, red teaming, war games, and similar exercises can all help. Global international organizations, alliances, and complex economic and social interdependence between great powers can also help to ensure nuclear weapons are not the only guarantor of great power peace.

The modeling of global cooling from nuclear war—often called nuclear winter—has been ongoing since Carl Sagan and team raised the concern in October 1983. The results of researchers vary drastically. When looking at the same regional nuclear war scenario, one group of researchers concluded the environmental harms could be globally catastrophic, while the other concluded the climate impact would be minimal. Assumptions regarding how much soot a nuclear war generates, how much soot reaches the upper atmosphere, how food consumption changes, effects on global trade, and the degree to which livestock feed is diverted to human use all affect estimated harm, sometimes drastically.

Unfortunately, political biases and agendas have often colored those assumptions. Fortunately, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine launched an independent study on potential environmental effects of nuclear war to assess the environmental effects and social consequences of nuclear war, including potential nuclear winter scenarios. The committee’s work continues, but the findings should merit significant attention. More generally, the global community should also invest financial, scientific, and computing resources to better assess the climate effects of nuclear detonations, connecting it with ongoing work on modeling climate change. Nuclear war would be a global problem that deserves global attention to understand and mitigate the effects.

The United States and global governments can also take action to reduce the risk of nuclear war causing existential harm by strengthening food security. Because the existential harm of a nuclear war that caused nuclear winter would come primarily through massive starvation, the global community can work together to build new and enhance existing long-term food reserves. In addition, the United States and others should think through and develop post-catastrophe plans for a broad range of extreme events, including nuclear war. For example, the United States could develop plans to use the military for emergency food supply, as in the Berlin airlift, when American and British aircraft delivered 2.3 million pounds of food, and other supplies to West Berlin. The United States and global community should also invest in research and development towards synthetic and resilient food sources like methane single cell proteins. These activities would not just be useful for life after nuclear war, but also enhance food security in the near term and be useful for a broad range of ecological and social disasters.

Of course, the best way to reduce the risks of nuclear war is to ensure it never happens in the first place.

The survival of humanity needs to be a global priority, because humanity’s survival transcends every social, economic, and political issue. What importance is war in the Ukraine, Taiwanese sovereignty, global poverty reduction, or Icelandic fishing rights, when all of mankind is in danger? For better or worse, ensuring human survival means keeping nuclear weapons for their deterrent effects, accompanied by diligent efforts to ensure that they are never used.

Keywords: TPNW, Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, existential risk, great power war, nuclear abolition, nuclear ban treaty

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons