The pathways of inadvertent escalation: Is a NATO-Russia war (now) possible?

By Ulrich Kühn

Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, February 24, 2022

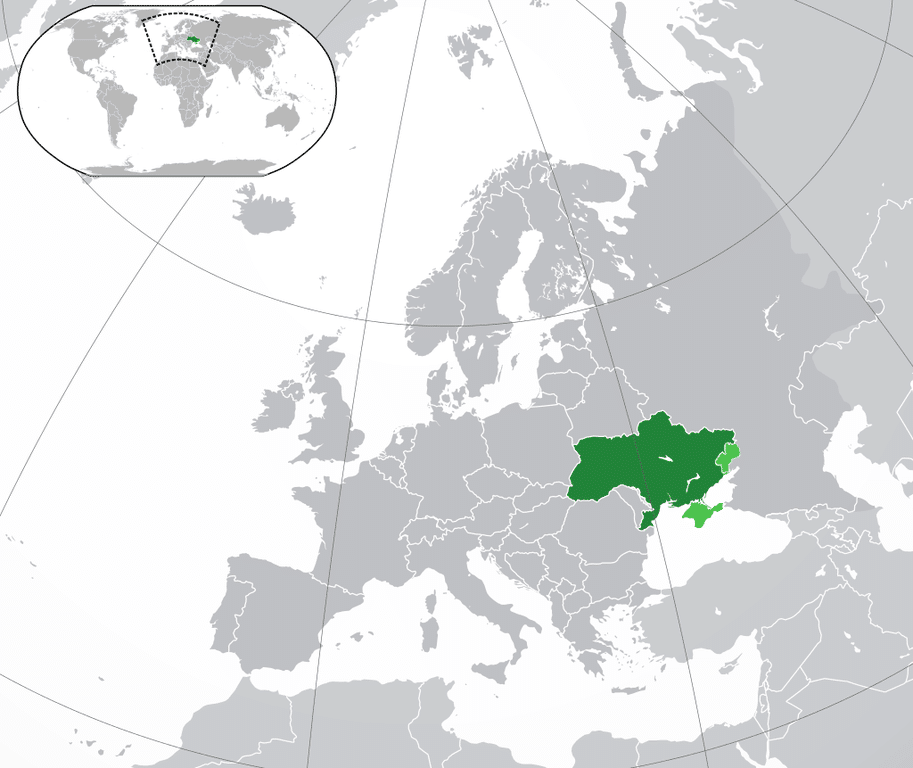

February 24, 2022 marks a historical watershed for global peace and security. Violating international law, Vladimir Putin of Russia has ordered an illegal full-fledged assault on the entire Ukraine. Russian forces are pouring into the country from at least four directions, following an initial shelling of Ukrainian airfields, air defense, command and control, and other strategic assets. Analysts, including myself, have warned of that grim scenario for months. Yet, diplomacy to avert war against Ukraine has failed.

President Biden and other Western leaders have made it clear repeatedly that they would not send forces to Ukraine. After all, the country is not a member of the NATO alliance. A deliberate decision by Western leaders to go to war with Russia over Ukraine should therefore not be expected. That does not mean, however, that unintended actions by Russia, by its proxy Belarus or by individual NATO member states could not spark a larger conflict that no one planned. During the next hours, days, and weeks, the risk of what strategists call “inadvertent escalation” will increase.

A report from the RAND Corporation from 2008 describes inadvertent escalation as occurring “when a combatant’s intentional actions are unintentionally escalatory, usually because they cross a threshold of intensity or scope in the conflict or confrontation that matters to the adversary but appears insignificant or is invisible to the party taking the action. Such a failure to anticipate the escalatory effects of an action can result from a lack of understanding of how the opponent will view the action, it may result from incorrectly anticipating the second- or third-order consequences of the action in question, or both.”

In Ukraine, Russian and perhaps Belarussian forces will most likely establish control over Ukraine’s borders with NATO member states Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania within the next hours and days. These borders—together with the borders that NATO members Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland share with Russia and Belarus—may soon become some sort of new “iron curtain.” That in itself would be bad enough for Europe. Even worse, however, they could become dangerous military contact zones with heightened risks of inadvertent escalation.

Already during the first hours of the Russian campaign, Russian aircraft and surface-to-surface missiles eliminated most of Ukraine’s air defense assets. Effectively, Russia has now established air dominance over Ukrainian airspace. The following hours and days will most likely see additional Russian air support for ground operations. What exactly that would mean and how any ground battles will play out cannot be said now. There is, however, a certain risk that Russian fighter jets, engaged in ground support operations, might inadvertently violate NATO airspace over Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, or Romania.

Incidents of such kind have happened in recent years and NATO forces usually respond swiftly by escorting any Russian air assets out of NATO airspace. The significant difference today is that similar incidents would take place against the background of an ongoing war at NATO’s borders. Whether Russian pilots, already under duress due to battle engagement, would be able to respond to NATO air policing in a responsible manner remains an open question. A first incident happened in the early hours of the Russian attack when a Suhoi 27, belonging to the Ukrainian Air Force, entered Romanian airspace and was escorted for immediate landing at the Bacău Air Base 95. The next days might see a number of dangerously close air encounters between Russian and NATO forces.

Another possible scenario for inadvertent escalation is linked to western calls for arming Ukrainian forces. A day before the Russian assault, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced, “the UK will shortly be providing a further package of military support to Ukraine. This will include lethal aid in the form of defensive weapons and non-lethal aid.” As morally justified such calls might sound in the current environment, the question remains: How will weapons be transferred to Ukraine, now that Russia has established air dominance over the country? They would almost certainly not be flown in but would have to be provided using land or sea routes. It would thus be in the interest of the Russian military to gain quick control over Ukraine’s western borders with NATO allies. Possible efforts by individual NATO member states to send additional military equipment via the Ukrainian land borders could be met with fierce Russian resistance and may lead to skirmishes between Russian and NATO personnel.

A somewhat similar grim scenario could unfold if America or other allies decide to back a Ukrainian insurgency by training and equipping Ukrainians on adjacent NATO territory. US officials have reportedly already discussed seeking to help any Ukrainian insurgency by training in nearby Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Again, NATO-backed insurgents would have to cross the Ukrainian border, thereby inviting possible Russian military action. In addition, such training activities would most likely involve intelligence personnel that, if captured by the Russians, could be put on public display with the aim of making the other side look weak. Back in 2014, Russian personnel captured an Estonian counter-intelligence officer in the Estonian security agency, Kapo, and paraded him on Russian TV just two days after then-President Barack Obama had visited the Baltic state.

On Twitter, security experts have started to debate additional scenarios. William Alberque, a former NATO official, pointed out that a wave of refugees that could soon pour into Eastern European states could create cross-border incidents related to management of a messy human situation or lead to infiltration and false flag operations. Alberque also mentioned inadvertent risks that could emanate from the formation of possible volunteer units of irregular forces from NATO allies, such as Poland, en route to engaging Russian troops in Ukraine.

Obviously, one can and should debate whether those scenarios are at all realistic and plausible. But one point is absolutely real: With an ongoing war in Europe, Russian and NATO forces could clash in the next hours, days or weeks—even though neither side intended any military escalation in the first place.

To prevent NATO from inadvertently ending up in a shooting war with Russia, Western allies need to do three things. First, they need to consult closely and assess internally which risks they deem acceptable and which risks they want to avoid and at what cost. Allies might find it useful to revisit some of the practical mechanisms to deconflict US-Russian military activities in Syria in that regard. Second, the allies should consider contingencies they did perhaps not focus on so far. Simulations involving experts from different disciplines could help to think through the scenarios. Third, the NATO allies must act in unity. Particularly, the issue of sending further lethal equipment to Ukraine should only be considered if all member states are fully on board. One of the worst outcomes would be an entrapment commitment—that is, a situation in which one ally establishes facts on the ground without the consent of the other allies and ends up in a military confrontation with Russia that pulls in the entire alliance.

The war in Ukraine signifies the end of an era. An era where Europe was mostly “whole and free,” to recall the famous 1989 dictum from George Bush senior. We do not know what the new era will look like. One thing is for certain, though: It will be less peaceful and safe, and more militarized and risky. Knowing about some of these risks is a necessary condition for closing inadvertent escalation pathways. But even that knowledge might not be sufficient, in the fog of war, to prevent a possibly devastating war between nuclear-armed adversaries.

As the coronavirus crisis shows, we need science now more than ever.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: NATO-Russia war, Russia-Ukraine, Ukraine, inadvertent escalation

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons