Trade Performance In EU Internal Market In Euro Era

John Weeks

European integration began as a political project to institutionalize peace and cooperation, with the Coal and Steel Community the initial step. In the late 1980s and into the 1990s, roughly coinciding with the end of the Cold War, priorities changed – from peace and cooperation to trade competitiveness.

The Treaty on European Union (TEU) formalized this shift (also known as the Treaty of Rome, subsequently amended by the Treaties of Amsterdam, Nice and Lisbon). Article 2, section 3 reads:

The Union shall establish an internal market. It shall work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy, aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment. [Eur-Lex, emphasis added]

The treaty makes political and ideological specifications for the European Union. It commits all member governments to a specific form of economic organization, a “market economy”. Other parts of the two major EU treaties make it clear that “market economy” is synonymous with “capitalism” (Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union is the other).

No constitution of a major country, even though it may have a capitalist economy, includes such an ideological commitment, with the possible exception of China’s (Smith and Weeks 2017). The treaty language further specifies that the EU economy be “highly competitive”. Because those words are used immediately following the mandate for “an internal market”, it is a reasonable inference that “highly competitive” means “trade competitive”.

Because the treaty section commits to “a highly competitive social market economy”, singular rather than plural, the referent must be the Union as a whole. Thus, Article 2(3) must refer to extra-EU trade: that the EU economy taken as a whole should be internationally competitive. This interpretation implies that the TEU makes a fundamental change from the concept of the early initiators of integration. Their focus was to facilitate intra-EU trade, through a customs union that would lay the basis for political integration.

Intra- and extra-EU trade patterns

By definition the purpose of a customs union is to give preference to trade among members. With that in mind we can assess if the intentions behind the wording in the TEU have affected the pattern of EU trade. At the beginning of this century the adoption of the euro represented a major institutional change affecting EU trade. One would expect the euro’s entry to reinforce intra-EU trade.

Internal EU regulations on product safety and related rules also impact on intra- and extra-EU trade. We should expect EU regulations to have a different impact on extra-EU imports than on extra-EU exports. Extra-EU imports must conform to intra-EU regulations, while extra-EU exports need not do so. The restrictive fiscal policies pressed upon national governments after 2010 represent a second possible depressor of intra-EU trade, due to their growth-reducing effects.

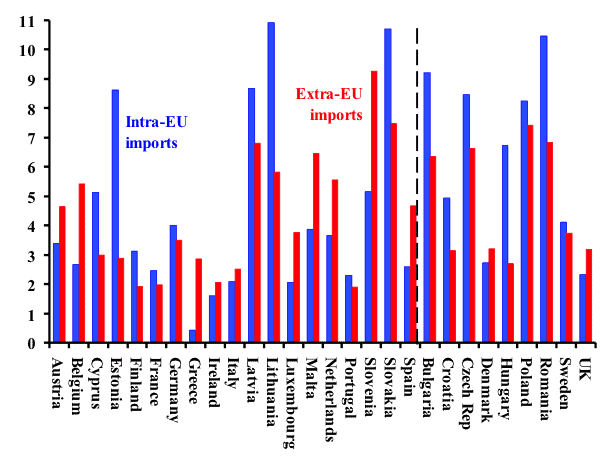

That extra-EU exports may face less regulation than extra-EU imports suggests the possibility of different patterns for exports and imports. The statistics indicate such a difference. Chart 1 shows annual rate of growth of intra- and extra-EU imports for the 19 Eurozone countries and the nine with national currencies from the introduction of the euro in 2001 through 2017. For the 19 Eurozone countries in a bare majority, 10 of 19, intra-EU import trade grew faster than extra-EU import trade. Among the non-euro countries in 7 of 9 intra-EU imports grew faster.

One would have expected the opposite result, faster growth of intra-imports for the euro group, not the non-euro group. A major purpose of the introduction of the euro was to reduce transactions costs, making trade more “seamless”. The statistics do not support that prediction. It appears that any cost-reducing role of the euro was outweighed by other effects.

One such effect might relate to level of development and structural characteristics. The ten countries in which intra-EU imports grew fastest were from the Baltic region or central Europe, countries in transition from centrally planned economies (annual rates in percentages): Lithuania (10.9), Slovakia (10.7), Romania (10.5), Bulgaria (9.2), Latvia (8.7), Estonia (8.6), Czech Republic (8.5), Poland (8.3), Hungary (6.7) and Slovenia (5.1). For all ten except Slovenia intra-imports grew faster than extra-imports. These statistics suggest that the euro has not facilitated intra-import trade.

Chart 1: Annual rates of growth of intra-EU imports and extra-EU imports, Eurozone and non-euro countries, 2001-2017 (percentages)

Note: Rate of growth calculated by using end years. Black line divides the 19 Eurozone members from the nine non-euro countries.

Source: Eurostat

The same statistics on exports is consistent with the hypothesis that EU rules have a relatively restrictive effect. Of the 28 countries, for only one, Bulgaria, did intra-EU exports grow faster than extra-EU exports, and for another the rates were the same to one decimal point (Sweden).

The statistics also cast doubt on the reputation of the German economy as an engine of export growth. Over the 17 years, German intra-EU exports grew slower than in 12 other EU countries (faster than 15); and for extra-EU exports 16 countries showed faster growth rates (eleven slower). The expanding German goods surplus resulted from relatively slow growth of imports compared to exports, rather than rapid export growth.

Chart 2: Annual rates of growth of intra-EU exports and extra-EU exports, Euro zone and non-euro countries, 2001-2017 (percentages)

Note: Rate of growth calculated by using end years. Black line divides the 19 Eurozone members from the nine non-euro countries.

Source: Eurostat

Peace, not trade

These statistics suggest a few conclusions. First, the EU internal market has integrated the formerly centrally planned countries into international commerce, though more so for imports than exports. Second, the EU internal market has not fostered trade growth relatively to the non-EU market. Its benefit to EU citizens is probably consumer protection rather than cheap goods, with the former the more important benefit. Third, the euro has not facilitated trade within the internal market, neither for imports nor for exports.

Many others have for several years argued that “benefits from trade” is a weak argument for EU membership. The statistics support that conclusion and indicate that it may apply to most EU members. The strongest arguments for membership are those put forward by the visionaries of European integration in the late 1940s, which are political and social, not economic. EU reform should be based on the sublime goals of peace and cooperation, not the commercial banality of export competitiveness.