Documentos extremamente relevantes sobre a queda do muti de Berlim, o processo de unificação da Alemanha e as garantias que os então estadistas ocidentais deram aos soviéticos (antes da implosão da URSS) de que a OTAN não se expandiria a Leste.

Disponíveis no site do National Security Archive, na George Washington University:

NATO Expansion: What Gorbachev Heard

Declassified documents show security assurances against NATO expansion to Soviet leaders from Baker, Bush, Genscher, Kohl, Gates, Mitterrand, Thatcher, Hurd, Major, and Woerner

Slavic Studies Panel Addresses “Who Promised What to Whom on NATO Expansion?”

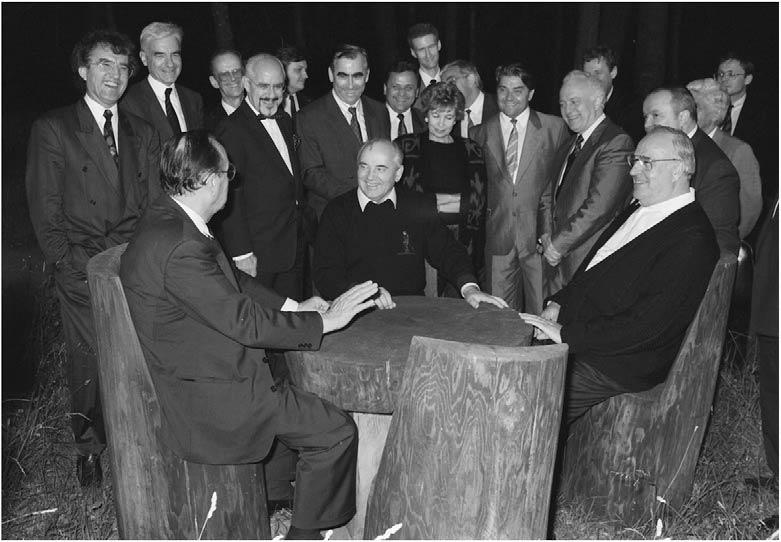

Washington D.C., December 12, 2017 – U.S. Secretary of State James Baker’s famous “not one inch eastward” assurance about NATO expansion in his meeting with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev on February 9, 1990, was part of a cascade of assurances about Soviet security given by Western leaders to Gorbachev and other Soviet officials throughout the process of German unification in 1990 and on into 1991, according to declassified U.S., Soviet, German, British and French documents posted today by the National Security Archive at George Washington University (http://nsarchive.gwu.edu).

The documents show that multiple national leaders were considering and rejecting Central and Eastern European membership in NATO as of early 1990 and through 1991, that discussions of NATO in the context of German unification negotiations in 1990 were not at all narrowly limited to the status of East German territory, and that subsequent Soviet and Russian complaints about being misled about NATO expansion were founded in written contemporaneous memcons and telcons at the highest levels.

The documents reinforce former CIA Director Robert Gates’s criticism of “pressing ahead with expansion of NATO eastward [in the 1990s], when Gorbachev and others were led to believe that wouldn’t happen.”[1]The key phrase, buttressed by the documents, is “led to believe.”

President George H.W. Bush had assured Gorbachev during the Malta summit in December 1989 that the U.S. would not take advantage (“I have not jumped up and down on the Berlin Wall”) of the revolutions in Eastern Europe to harm Soviet interests; but neither Bush nor Gorbachev at that point (or for that matter, West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl) expected so soon the collapse of East Germany or the speed of German unification.[2]

The first concrete assurances by Western leaders on NATO began on January 31, 1990, when West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher opened the bidding with a major public speech at Tutzing, in Bavaria, on German unification. The U.S. Embassy in Bonn (see Document 1) informed Washington that Genscher made clear “that the changes in Eastern Europe and the German unification process must not lead to an ‘impairment of Soviet security interests.’ Therefore, NATO should rule out an ‘expansion of its territory towards the east, i.e. moving it closer to the Soviet borders.’” The Bonn cable also noted Genscher’s proposal to leave the East German territory out of NATO military structures even in a unified Germany in NATO.[3]

This latter idea of special status for the GDR territory was codified in the final German unification treaty signed on September 12, 1990, by the Two-Plus-Four foreign ministers (see Document 25). The former idea about “closer to the Soviet borders” is written down not in treaties but in multiple memoranda of conversation between the Soviets and the highest-level Western interlocutors (Genscher, Kohl, Baker, Gates, Bush, Mitterrand, Thatcher, Major, Woerner, and others) offering assurances throughout 1990 and into 1991 about protecting Soviet security interests and including the USSR in new European security structures. The two issues were related but not the same. Subsequent analysis sometimes conflated the two and argued that the discussion did not involve all of Europe. The documents published below show clearly that it did.

The “Tutzing formula” immediately became the center of a flurry of important diplomatic discussions over the next 10 days in 1990, leading to the crucial February 10, 1990, meeting in Moscow between Kohl and Gorbachev when the West German leader achieved Soviet assent in principle to German unification in NATO, as long as NATO did not expand to the east. The Soviets would need much more time to work with their domestic opinion (and financial aid from the West Germans) before formally signing the deal in September 1990.

The conversations before Kohl’s assurance involved explicit discussion of NATO expansion, the Central and East European countries, and how to convince the Soviets to accept unification. For example, on February 6, 1990, when Genscher met with British Foreign Minister Douglas Hurd, the British record showed Genscher saying, “The Russians must have some assurance that if, for example, the Polish Government left the Warsaw Pact one day, they would not join NATO the next.” (See Document 2)

Having met with Genscher on his way into discussions with the Soviets, Baker repeated exactly the Genscher formulation in his meeting with Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze on February 9, 1990, (see Document 4); and even more importantly, face to face with Gorbachev.

Not once, but three times, Baker tried out the “not one inch eastward” formula with Gorbachev in the February 9, 1990, meeting. He agreed with Gorbachev’s statement in response to the assurances that “NATO expansion is unacceptable.” Baker assured Gorbachev that “neither the President nor I intend to extract any unilateral advantages from the processes that are taking place,” and that the Americans understood that “not only for the Soviet Union but for other European countries as well it is important to have guarantees that if the United States keeps its presence in Germany within the framework of NATO, not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction.” (See Document 6)

Afterwards, Baker wrote to Helmut Kohl who would meet with the Soviet leader on the next day, with much of the very same language. Baker reported: “And then I put the following question to him [Gorbachev]. Would you prefer to see a united Germany outside of NATO, independent and with no U.S. forces or would you prefer a unified Germany to be tied to NATO, with assurances that NATO’s jurisdiction would not shift one inch eastward from its present position? He answered that the Soviet leadership was giving real thought to all such options [….] He then added, ‘Certainly any extension of the zone of NATO would be unacceptable.’” Baker added in parentheses, for Kohl’s benefit, “By implication, NATO in its current zone might be acceptable.” (See Document 8)

Well-briefed by the American secretary of state, the West German chancellor understood a key Soviet bottom line, and assured Gorbachev on February 10, 1990: “We believe that NATO should not expand the sphere of its activity.” (See Document 9) After this meeting, Kohl could hardly contain his excitement at Gorbachev’s agreement in principle for German unification and, as part of the Helsinki formula that states choose their own alliances, so Germany could choose NATO. Kohl described in his memoirs walking all night around Moscow – but still understanding there was a price still to pay.

All the Western foreign ministers were on board with Genscher, Kohl, and Baker. Next came the British foreign minister, Douglas Hurd, on April 11, 1990. At this point, the East Germans had voted overwhelmingly for the deutschmark and for rapid unification, in the March 18 elections in which Kohl had surprised almost all observers with a real victory. Kohl’s analyses (first explained to Bush on December 3, 1989) that the GDR’s collapse would open all possibilities, that he had to run to get to the head of the train, that he needed U.S. backing, that unification could happen faster than anyone thought possible – all turned out to be correct. Monetary union would proceed as early as July and the assurances about security kept coming. Hurd reinforced the Baker-Genscher-Kohl message in his meeting with Gorbachev in Moscow, April 11, 1990, saying that Britain clearly “recognized the importance of doing nothing to prejudice Soviet interests and dignity.” (See Document 15)

The Baker conversation with Shevardnadze on May 4, 1990, as Baker described it in his own report to President Bush, most eloquently described what Western leaders were telling Gorbachev exactly at the moment: “I used your speech and our recognition of the need to adapt NATO, politically and militarily, and to develop CSCE to reassure Shevardnadze that the process would not yield winners and losers. Instead, it would produce a new legitimate European structure – one that would be inclusive, not exclusive.” (See Document 17)

Baker said it again, directly to Gorbachev on May 18, 1990 in Moscow, giving Gorbachev his “nine points,” which included the transformation of NATO, strengthening European structures, keeping Germany non-nuclear, and taking Soviet security interests into account. Baker started off his remarks, “Before saying a few words about the German issue, I wanted to emphasize that our policies are not aimed at separating Eastern Europe from the Soviet Union. We had that policy before. But today we are interested in building a stable Europe, and doing it together with you.” (See Document 18)

The French leader Francois Mitterrand was not in a mind-meld with the Americans, quite the contrary, as evidenced by his telling Gorbachev in Moscow on May 25, 1990, that he was “personally in favor of gradually dismantling the military blocs”; but Mitterrand continued the cascade of assurances by saying the West must “create security conditions for you, as well as European security as a whole.” (See Document 19) Mitterrand immediately wrote Bush in a “cher George” letter about his conversation with the Soviet leader, that “we would certainly not refuse to detail the guarantees that he would have a right to expect for his country’s security.” (See Document 20)

At the Washington summit on May 31, 1990, Bush went out of his way to assure Gorbachev that Germany in NATO would never be directed at the USSR: “Believe me, we are not pushing Germany towards unification, and it is not us who determines the pace of this process. And of course, we have no intention, even in our thoughts, to harm the Soviet Union in any fashion. That is why we are speaking in favor of German unification in NATO without ignoring the wider context of the CSCE, taking the traditional economic ties between the two German states into consideration. Such a model, in our view, corresponds to the Soviet interests as well.” (See Document 21)

The “Iron Lady” also pitched in, after the Washington summit, in her meeting with Gorbachev in London on June 8, 1990. Thatcher anticipated the moves the Americans (with her support) would take in the early July NATO conference to support Gorbachev with descriptions of the transformation of NATO towards a more political, less militarily threatening, alliance. She said to Gorbachev: “We must find ways to give the Soviet Union confidence that its security would be assured…. CSCE could be an umbrella for all this, as well as being the forum which brought the Soviet Union fully into discussion about the future of Europe.” (See Document 22)

The NATO London Declaration on July 5, 1990 had quite a positive effect on deliberations in Moscow, according to most accounts, giving Gorbachev significant ammunition to counter his hardliners at the Party Congress which was taking place at that moment. Some versions of this history assert that an advance copy was provided to Shevardnadze’s aides, while others describe just an alert that allowed those aides to take the wire service copy and produce a Soviet positive assessment before the military or hardliners could call it propaganda.

As Kohl said to Gorbachev in Moscow on July 15, 1990, as they worked out the final deal on German unification: “We know what awaits NATO in the future, and I think you are now in the know as well,” referring to the NATO London Declaration. (See Document 23)

In his phone call to Gorbachev on July 17, Bush meant to reinforce the success of the Kohl-Gorbachev talks and the message of the London Declaration. Bush explained: “So what we tried to do was to take account of your concerns expressed to me and others, and we did it in the following ways: by our joint declaration on non-aggression; in our invitation to you to come to NATO; in our agreement to open NATO to regular diplomatic contact with your government and those of the Eastern European countries; and our offer on assurances on the future size of the armed forces of a united Germany – an issue I know you discussed with Helmut Kohl. We also fundamentally changed our military approach on conventional and nuclear forces. We conveyed the idea of an expanded, stronger CSCE with new institutions in which the USSR can share and be part of the new Europe.” (See Document 24)

The documents show that Gorbachev agreed to German unification in NATO as the result of this cascade of assurances, and on the basis of his own analysis that the future of the Soviet Union depended on its integration into Europe, for which Germany would be the decisive actor. He and most of his allies believed that some version of the common European home was still possible and would develop alongside the transformation of NATO to lead to a more inclusive and integrated European space, that the post-Cold War settlement would take account of the Soviet security interests. The alliance with Germany would not only overcome the Cold War but also turn on its head the legacy of the Great Patriotic War.

But inside the U.S. government, a different discussion continued, a debate about relations between NATO and Eastern Europe. Opinions differed, but the suggestion from the Defense Department as of October 25, 1990 was to leave “the door ajar” for East European membership in NATO. (See Document 27) The view of the State Department was that NATO expansion was not on the agenda, because it was not in the interest of the U.S. to organize “an anti-Soviet coalition” that extended to the Soviet borders, not least because it might reverse the positive trends in the Soviet Union. (See Document 26) The Bush administration took the latter view. And that’s what the Soviets heard.

As late as March 1991, according to the diary of the British ambassador to Moscow, British Prime Minister John Major personally assured Gorbachev, “We are not talking about the strengthening of NATO.” Subsequently, when Soviet defense minister Marshal Dmitri Yazov asked Major about East European leaders’ interest in NATO membership, the British leader responded, “Nothing of the sort will happen.” (See Document 28)

When Russian Supreme Soviet deputies came to Brussels to see NATO and meet with NATO secretary-general Manfred Woerner in July 1991, Woerner told the Russians that “We should not allow […] the isolation of the USSR from the European community.” According to the Russian memorandum of conversation, “Woerner stressed that the NATO Council and he are against the expansion of NATO (13 of 16 NATO members support this point of view).” (See Document 30)

Thus, Gorbachev went to the end of the Soviet Union assured that the West was not threatening his security and was not expanding NATO. Instead, the dissolution of the USSR was brought about by Russians (Boris Yeltsin and his leading advisory Gennady Burbulis) in concert with the former party bosses of the Soviet republics, especially Ukraine, in December 1991. The Cold War was long over by then. The Americans had tried to keep the Soviet Union together (see the Bush “Chicken Kiev” speech on August 1, 1991). NATO’s expansion was years in the future, when these disputes would erupt again, and more assurances would come to Russian leader Boris Yeltsin.

The Archive compiled these declassified documents for a panel discussion on November 10, 2017 at the annual conference of the Association for Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) in Chicago under the title “Who Promised What to Whom on NATO Expansion?” The panel included:

* Mark Kramer from the Davis Center at Harvard, editor of the Journal of Cold War Studies, whose 2009 Washington Quarterly article argued that the “no-NATO-enlargement pledge” was a “myth”;[4]

* Joshua R. Itkowitz Shifrinson from the Bush School at Texas A&M, whose 2016 International Security article argued the U.S. was playing a double game in 1990, leading Gorbachev to believe NATO would be subsumed in a new European security structure, while working to ensure hegemony in Europe and the maintenance of NATO;[5]

* James Goldgeier from American University, who wrote the authoritative book on the Clinton decision on NATO expansion, Not Whether But When, and described the misleading U.S. assurances to Russian leader Boris Yeltsin in a 2016 WarOnTheRocks article;[6]

* Svetlana Savranskaya and Tom Blanton from the National Security Archive, whose most recent book, The Last Superpower Summits: Gorbachev, Reagan, and Bush: Conversations That Ended the Cold War (CEU Press, 2016) analyzes and publishes the declassified transcripts and related documents from all of Gorbachev’s summits with U.S. presidents, including dozens of assurances about protecting the USSR’s security interests.[7]

[Today’s posting is the first of two on the subject. The second part will cover the Yeltsin discussions with Western leaders about NATO.]

READ THE DOCUMENTS

Document 01

U.S. Department of State. FOIA Reading Room. Case F-2015 10829

One of the myths about the January and February 1990 discussions of German unification is that these talks occurred so early in the process, with the Warsaw Pact still very much in existence, that no one was thinking about the possibility that Central and European countries, even then members of the Warsaw Pact, could in the future become members of NATO. On the contrary, the West German foreign minister’s Tutzing formula in his speech of January 31, 1990, widely reported in the media in Europe, Washington, and Moscow, explicitly addressed the possibility of NATO expansion, as well as Central and Eastern European membership in NATO – and denied that possibility, as part of his olive garland towards Moscow. This U.S. Embassy Bonn cable reporting back to Washington details both of Hans-Dietrich Genscher’s proposals – that NATO would not expand to the east, and that the former territory of the GDR in a unified Germany would be treated differently from other NATO territory.

Document 02

The U.S. State Department’s subsequent view of the German unification negotiations, expressed in a 1996 cable sent to all posts, mistakenly asserts that the entire negotiation over the future of Germany limited its discussion of the future of NATO to the specific arrangements over the territory of the former GDR. Perhaps the American diplomats missed out on the early dialogue between the British and the Germans on this issue, even though both shared their views with the U.S. secretary of state. As published in the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s official 2010 documentary history of the UK’s input into German unification, this memorandum of British Foreign Minister Douglas Hurd’s conversation with West German Foreign Minister Genscher on February 6, 1990, contains some remarkable specificity on the issue of future NATO membership for the Central Europeans. The British memorandum specifically quotes Genscher as saying “that when he talked about not wanting to extend NATO that applied to other states beside the GDR. The Russians must have some assurance that if, for example, the Polish Government left the Warsaw Pact one day, they would not join NATO the next.” Genscher and Hurd were saying the same to their Soviet counterpart Eduard Shevardnadze, and to James Baker.[8]

Document 03

George H. W. Bush Presidential Library

This concise note to President Bush from one of the Cold War’s architects, Paul Nitze (based at his namesake Johns Hopkins University School of International Studies), captures the debate over the future of NATO in early 1990. Nitze relates that Central and Eastern European leaders attending the “Forum for Germany” conference in Berlin were advocating the dissolution of both the superpower blocs, NATO and the Warsaw Pact, until he (and a few western Europeans) turned around that view and instead emphasized the importance of NATO as the basis of stability and U.S. presence in Europe.

Document 04

U.S. Department of State, FOIA 199504567 (National Security Archive Flashpoints Collection, Box 38)

Although heavily redacted compared to the Soviet accounts of these conversations, the official State Department version of Secretary Baker’s assurances to Soviet Foreign Minister Shevardnadze just before the formal meeting with Gorbachev on February 9, 1990, contains a series of telling phrases. Baker proposes the Two-Plus-Four formula, with the two being the Germanies and the four the post-war occupying powers; argues against other ways to negotiate unification; and makes the case for anchoring Germany in NATO. Furthermore, Baker tells the Soviet foreign minister, “A neutral Germany would undoubtedly acquire its own independent nuclear capability. However, a Germany that is firmly anchored in a changed NATO, by that I mean a NATO that is far less of [a] military organization, much more of a political one, would have no need for independent capability. There would, of course, have to be iron-clad guarantees that NATO’s jurisdiction or forces would not move eastward. And this would have to be done in a manner that would satisfy Germany’s neighbors to the east.”

Document 05

U.S. Department of State, FOIA 199504567 (National Security Archive Flashpoints Collection, Box 38)

Even with (unjustified) redactions by U.S. classification officers, this American transcript of perhaps the most famous U.S. assurance to the Soviets on NATO expansion confirms the Soviet transcript of the same conversation. Repeating what Bush said at the Malta summit in December 1989, Baker tells Gorbachev: “The President and I have made clear that we seek no unilateral advantage in this process” of inevitable German unification. Baker goes on to say, “We understand the need for assurances to the countries in the East. If we maintain a presence in a Germany that is a part of NATO, there would be no extension of NATO’s jurisdiction for forces of NATO one inch to the east.” Later in the conversation, Baker poses the same position as a question, “would you prefer a united Germany outside of NATO that is independent and has no US forces or would you prefer a united Germany with ties to NATO and assurances that there would be no extension of NATO’s current jurisdiction eastward?” The declassifiers of this memcon actually redacted Gorbachev’s response that indeed such an expansion would be “unacceptable” – but Baker’s letter to Kohl the next day, published in 1998 by the Germans, gives the quote.

Document 06

Gorbachev Foundation Archive, Fond 1, Opis 1.

This Gorbachev Foundation record of the Soviet leader’s meeting with James Baker on February 9, 1990, has been public and available for researchers at the Foundation since as early as 1996, but it was not published in English until 2010 when the Masterpieces of Historyvolume by the present authors came out from Central European University Press. The document focuses on German unification, but also includes candid discussion by Gorbachev of the economic and political problems in the Soviet Union, and Baker’s “free advice” (“sometimes the finance minister in me wakes up”) on prices, inflation, and even the policy of selling apartments to soak up the rubles cautious Soviet citizens have tucked under their mattresses.

Turning to German unification, Baker assures Gorbachev that “neither the president nor I intend to extract any unilateral advantages from the processes that are taking place,” and that the Americans understand the importance for the USSR and Europe of guarantees that “not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction.” Baker argues in favor of the Two-Plus-Four talks using the same assurance: “We believe that consultations and discussions within the framework of the ‘two+four’ mechanism should guarantee that Germany’s unification will not lead to NATO’s military organization spreading to the east.” Gorbachev responds by quoting Polish President Wojciech Jaruzelski: “that the presence of American and Soviet troops in Europe is an element of stability.”

The key exchange takes place when Baker asks whether Gorbachev would prefer “a united Germany outside of NATO, absolutely independent and without American troops; or a united Germany keeping its connections with NATO, but with the guarantee that NATO’s jurisdiction or troops will not spread east of the present boundary.” Thus, in this conversation, the U.S. secretary of state three times offers assurances that if Germany were allowed to unify in NATO, preserving the U.S. presence in Europe, then NATO would not expand to the east. Interestingly, not once does he use the term GDR or East Germany or even mention the Soviet troops in East Germany. For a skilled negotiator and careful lawyer, it seems very unlikely Baker would not use specific terminology if in fact he was referring only to East Germany.

The Soviet leader responds that “[w]e will think everything over. We intend to discuss all these questions in depth at the leadership level. It goes without saying that a broadening of the NATO zone is not acceptable.” Baker affirms: “We agree with that.”

Document 07

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, NSC Scowcroft Files, Box 91128, Folder “Gorbachev (Dobrynin) Sensitive.”

This conversation is especially important because subsequent researchers have speculated that Secretary Baker may have been speaking beyond his brief in his “not one inch eastward” conversation with Gorbachev. Robert Gates, the former top CIA intelligence analyst and a specialist on the USSR, here tells his kind-of-counterpart, the head of the KGB, in his office at the Lubyanka KGB headquarters, exactly what Baker told Gorbachev that day at the Kremlin: not one inch eastward. At that point, Gates was the top deputy to the president’s national security adviser, Gen. Brent Scowcroft, so this document speaks to a coordinated approach by the U.S. government to Gorbachev. Kryuchkov, whom Gorbachev appointed to replace Viktor Chebrikov at the KGB in October 1988, comes across here as surprisingly progressive on many issues of domestic reform. He talks openly about the shortcomings and problems of perestroika, the need to abolish the leading role of the CPSU, the central government’s mistaken neglect of ethnic issues, the “atrocious” pricing system, and other domestic topics.

When the discussion moves on to foreign policy, in particular the German question, Gates asks, “What did Kryuchkov think of the Kohl/Genscher proposal under which a united Germany would be associated with NATO, but in which NATO troops would move no further east than they now were? It seems to us to be a sound proposal.” Kryuchkov does not give a direct answer but talks about how sensitive the issue of German unification is for the Soviet public and suggests that the Germans should offer the Soviet Union some guarantees. He says that although Kohl and Genscher’s ideas are interesting, “even those points in their proposals with which we agree would have to have guarantees. We learned from the Americans in arms control negotiations the importance of verification, and we would have to be sure.”

Document 08

This key document first appeared in Helmut Kohl’s scholarly edition of chancellery documents on German unification, published in 1998. Kohl at that moment was caught up in an election campaign that would end his 16-year tenure as chancellor, and wanted to remind Germans of his instrumental role in the triumph of unification.[9] The large volume (over 1,000 pages) included German texts of Kohl’s meetings with Gorbachev, Bush, Mitterrand, Thatcher and more – all published with no apparent consultation with those governments, only eight years after the events. A few of the Kohl documents, such as this one, appear in English, representing the American or British originals rather than German notes or translations. Here, Baker debriefs Kohl the day after his February 9 meeting with Gorbachev. (The chancellor is scheduled to have his own session with Gorbachev on February 10 in Moscow.) The American apprises the German on Soviet “concerns” about unification, and summarizes why a “Two Plus Four” negotiation would be the most appropriate venue for talks on the “external aspects of unification” given that the “internal aspects … were strictly a German matter.” Baker especially remarks on Gorbachev’s noncommittal response to the question about a neutral Germany versus a NATO Germany with pledges against eastward expansion, and advises Kohl that Gorbachev “may well be willing to go along with a sensible approach that gives him some cover …” Kohl reinforces this message in his own conversation later that day with the Soviet leader.

Document 09

This meeting in Moscow was the moment, by Kohl’s account, when he first heard from Gorbachev that the Soviet leader saw German unification as inevitable, that the value of future German friendship in a “common European home” outweighed Cold War rigidities, but that the Soviets would need time (and money) before they could acknowledge the new realities. Prepared by Baker’s letter and his own foreign minister’s Tutzing formula, Kohl early in the conversation assures Gorbachev, “We believe that NATO should not expand the sphere of its activity. We have to find a reasonable resolution. I correctly understand the security interests of the Soviet Union, and I realize that you, Mr. General Secretary, and the Soviet leadership will have to clearly explain what is happening to the Soviet people.” Later the two leaders tussle about NATO and the Warsaw Pact, with Gorbachev commenting, “They say what is NATO without the FRG. But we could also ask: what is the WTO without the GDR?” When Kohl disagrees, Gorbachev calls merely for “reasonable solutions that do not poison the atmosphere in our relations” and says this part of the conversation should not be made public.

Gorbachev aide Andrei Grachev later wrote that the Soviet leader early on understood that Germany was the door to European integration, and “[a]ll the attempted bargaining [by Gorbachev] about the final formula for German association with NATO was therefore much more a question of form than serious content; Gorbachev was trying to gain needed time in order to let public opinion at home adjust to the new reality, to the new type of relations that were taking shape in the Soviet Union’s relations with Germany as well as with the West in general. At the same time he was hoping to get at least partial political compensation from his Western partners for what he believed to be his major contribution to the end of the Cold War.”[10]

Document 10-1

Hoover Institution Archive, Stepanov-Mamaladze Collection.

Soviet Foreign Minister Shevardnadze was particularly unhappy with the swift pace of events on German unification, especially when a previously scheduled NATO and Warsaw Pact foreign ministers’ meeting in Ottawa, Canada, on February 10-12, 1990, that was meant to discuss the “Open Skies” treaty, turned into a wide-ranging negotiation over Germany and the installation of the Two-Plus-Four process to work out the details. Shevardnadze’s aide, Teimuraz Stepanov-Mamaladze, wrote notes of the Ottawa meetings in a series of notebooks, and also kept a less-telegraphic diary, which needs to be read along with the notebooks for the most complete account. Now deposited at the Hoover Institution, these excerpts of the Stepanov-Mamaladze notes and diary record Shevardnadze’s disapproval of the speed of the process, but most importantly reinforce the importance of the February 9 and 10 meetings in Moscow, where Western assurances about Soviet security were heard, and Gorbachev’s assent in principle to eventual German unification came as part of the deal.

Notes from the first days of the conference are very brief, but they contain one important line that shows that Baker offered the same assurance formula in Ottawa as he did in Moscow: “And if U[nited] G[ermany] stays in NATO, we should take care about nonexpansion of its jurisdiction to the East.” Shevardnadze is not ready to discuss conditions for German unification; he says that he has to consult with Moscow before any condition is approved. On February 13, according to the notes, Shevardnadze complains, “I am in a stupid situation – we are discussing the Open Skies, but my colleagues are talking about unification of Germany as if it was a fact.” The notes show that Baker was very persistent in trying to get Shevardnadze to define Soviet conditions for German unification in NATO, while Shevardnadze was still uncomfortable with the term “unification,” instead insisting on the more general term “unity.”

Document 10-2

Hoover Institution Archive, Stepanov-Mamaladze Collection.

This diary entry from February 12 contains a very brief description of the February 10 Kohl and Genscher visit to Moscow, about which Stepanov-Mamaladze had not previously written (since he was not present). Sharing the view of his minister, Shevardnadze, Stepanov reflects on the hurried nature of, and insufficient considerations given to, the Moscow discussions: “Before our visit here, Kohl and Genscher paid a hasty visit to Moscow. And just as hastily – in the opinion of E.A. [Shevardnadze] – Gorbachev accepted the right of the Germans to unity and self-determination.” This diary entry is evidence, from a critical perspective, that the United States and West Germany did give Moscow concrete assurances about keeping NATO to its current size and scope. In fact, the diary further indicates that at least in Shevardnadze’s view those assurances amounted to a deal – which Gorbachev accepted, even while he stalled for time.

Document 10-3

Hoover Institution Archive, Stepanov-Mamaladze Collection.

On the second day of the Ottawa conference, Stepanov-Mamaladze describes difficult negotiations about the exact wording on the joint statement on Germany and the Two-Plus-Four process. Shevardnadze and Genscher argued for two hours over the terms “unity” versus “unification” as Shevardnadze tried to slow things down on Germany and get the other ministers to concentrate on Open Skies. The day was quite intense: “During the day, active games were taking place between all of them. E.A. [Shevardnadze] met with Baker five times, twice with Genscher, talked with Fischer [GDR foreign minister], Dumas [French foreign minister], and the ministers of the ATS countries,” and finally, the text of the settlement was settled, using the word “unity.” The final statement also called the agreement on U.S. and Soviet troops in Central Europe the main achievement of the conference. But for the Soviet delegates, “ the ‘Open Sky’ [was] still closed by the storm cloud of Germany.”

Document 11

State Department FOIA release, National Security Archive Flashpoints Collection, Box 38.

This memo, likely authored by top Baker aide Robert Zoellick at the State Department, contains the candid American view of the Two-Plus-Four process with its advantages of “maintain[ing] American involvement in (and even some control over) the unification debate.” The American fear was that the West Germans would make their own deal with Moscow for rapid unification, giving up some of the bottom lines for the U.S., mainly membership in NATO. Zoellick points out, for example, that Kohl had announced his 10 Points without consulting Washington and after signals from Moscow, and that the U.S. had found out about Kohl going to Moscow from the Soviets, not from Kohl. The memo pre-empts objections about including the Soviets by pointing out they were already in Germany and had to be dealt with. The Two-Plus-Four arrangement includes the Soviets but prevents them from having a veto (which a Four-Power process or a United Nations process might allow), while an effective One-Plus-Three conversation before each meeting would enable West Germany and the U.S., with the British and the French, to work out a common position. Especially telling are the underlining and handwriting by Baker in the margins, especially his exuberant phrase, “you haven’t seen a leveraged buyout until you see this one!”

Document 12-1

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons (https://bush41library.tamu.edu/)

These conversations might be called “the education of Vaclav Havel,”[10] as the former dissident-turned-president of Czechoslovakia visited Washington only two months after the Velvet Revolution swept him from prison to the Prague Castle. Havel would enjoy standing ovations during a February 21 speech to a joint session of Congress, and hold talks with Bush before and after the congressional appearance. Havel had already been cited by journalists as calling for the dissolution of the Cold War blocs, both NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and the withdrawal of troops, so Bush took the opportunity to lecture the Czech leader about the value of NATO and its essential role as the basis for the U.S. presence in Europe. Still, Havel twice mentioned in his speech to Congress his hope that “American soldiers shouldn’t have to be separated from their mothers” just because Europe couldn’t keep the peace, and appealed for a “future democratic Germany in the process of unifying itself into a new pan-European structure which could decide about its own security system.” But afterwards, talking again to Bush, the former dissident clearly had gotten the message. Havel said he might have been misunderstood, that he certainly saw the value of U.S. engagement in Europe. For his part, Bush raised the possibilities, assuming more Czechoslovak cooperation on this issue, of U.S. investment and aid.

Document 12-2

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons (https://bush41library.tamu.edu/)

This memcon after Havel’s triumphant speech to Congress contains Bush’s request to Havel to pass the message to Gorbachev that the Americans support him personally, and that “We will not conduct ourselves in the wrong way by saying ‘we win, you lose.’” Emphasizing the point, Bush says, “tell Gorbachev that … I asked you to tell Gorbachev that we will not conduct ourselves regarding Czechoslovakia or any other country in a way that would complicate the problems he has so frankly discussed with me.” The Czechoslovak leader adds his own caution to the Americans about how to proceed with the unification of Germany and address Soviet insecurities. Havel remarks to Bush, “It is a question of prestige. This is the reason why I talked about the new European security system without mentioning NATO. Because, if it grew out of NATO, it would have to be named something else, if only because of the element of prestige. If NATO takes over Germany, it will look like defeat, one superpower conquering another. But if NATO can transform itself – perhaps in conjunction with the Helsinki process – it would look like a peaceful process of change, not defeat.” Bush responded positively: “You raised a good point. Our view is that NATO would continue with a new political role and that we would build on the CSCE process. We will give thought on how we might proceed.”

Document 13

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons (https://bush41library.tamu.edu/)

The Bush administration’s main worry about German unification as the process accelerated in February 1990 was that the West Germans might make their own deal bilaterally with the Soviets (see Document 11) and might be willing to bargain away NATO membership. President Bush later commented that the purpose of the Camp David meeting with Kohl was to “keep Germany on the NATO reservation,” and that drove the agenda for this set of meetings. The German chancellor arrives at Camp David without Genscher because the latter does not entirely share the Bush-Kohl position on full German membership in NATO, and he recently angered both leaders by speaking publicly about the CSCE as the future European security mechanism.[12]

At the beginning of this conversation, Kohl expresses gratitude for Bush and Baker’s support during his discussions with Gorbachev in Moscow in early February, especially for Bush’s letter stating Washington’s strong commitment to German unification in NATO. Both leaders express the need for the closest cooperation between them in order to reach the desired outcome. Bush’s priority is to keep the U.S. presence, especially the nuclear umbrella, in Europe: “if U.S. nuclear forces are withdrawn from Germany, I don’t see how we can persuade any other ally on the continent to retain these weapons.” He refers sarcastically to criticisms coming from Capitol Hill: “We have weird thinking in our Congress today, ideas like this peace dividend. We can’t do that in these uncertain times.” Both leaders are concerned about the position Gorbachev might take and agree on the need to consult with him regularly. Kohl suggests that the Soviets need assistance and the final arrangement on Germany could be a “matter of cash.” Foreshadowing his reluctance to contribute financially, Bush replies, “you have deep pockets.” At one point in the conversation, Bush seems to view his Soviet counterpart not as a partner but as a defeated enemy. Referring to talk in some Soviet quarters against Germany staying in NATO, he says: “To hell with that. We prevailed and they didn’t. We cannot let the Soviets clutch victory from the jaws of defeat.”

Document 14

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons (https://bush41library.tamu.edu/)

Foreign Minister Shevardnadze delivers a letter to Bush from Gorbachev, in which the Soviet president reviews the main issues before the coming summit. Economic issues are at the top of the list for the Soviet Union, specifically Most Favored Nation status and a trade agreement with the United States. Shevardnadze expresses concern about the lack of progress on these issues and the U.S. efforts to prevent the EBRD from extending loans to the USSR. He stresses that they are not asking for help, “we are only looking to be treated as partners.” Addressing the tensions in Lithuania, Bush says that he does not want to create difficulties for Gorbachev on domestic issues, but notes that he must insist on the rights of Lithuanians because their incorporation within the USSR was never recognized by the United States. On arms control, both sides point to some backtracking by the other and express a desire to finalize the START Treaty quickly. Shevardnadze mentions the upcoming CSCE summit and the Soviet expectation that it will discuss the new European security structures. Bush does not contradict this but ties it to the issues of the U.S. presence in Europe and German unification in NATO. He declares that he wants to “contribute to stability and to the creation of a Europe whole and free, or as you call it, a common European home. A[n] idea that is very close to our own.” The Soviets—wrongly—interpret this as a declaration that the U.S. administration shares Gorbachev’s idea.

Document 15

Ambassador Braithwaite’s telegram summarizes the meeting between Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs Douglas Hurd and President Gorbachev, noting Gorbachev’s “expansive mood.” Gorbachev asks the secretary to pass his appreciation for Margaret Thatcher’s letter to him after her summit with Kohl, at which, according to Gorbachev, she followed the lines of policy Gorbachev and Thatcher discussed in their recent phone call, on the basis of which the Soviet leader concluded that “the British and Soviet positions were very close indeed.” Hurd cautions Gorbachev that their positions are not 100% in agreement, but that the British “recognized the importance of doing nothing to prejudice Soviet interests and dignity.” Gorbachev, as reflected in Braithwaite’s summary, speaks about the importance of building new security structures as a way of dealing with the issue of two Germanies: “If we are talking about a common dialogue about a new Europe stretching from the Atlantic to the Urals, that was one way of dealing with the German issue.” That would require a transitional period to pick up the pace of the European process and “synchronise it with finding a solution to the problem of the two Germanies.” However, if the process was unilateral – only Germany in NATO and no regard for Soviet security interest – the Supreme Soviet would be very unlikely to approve such a solution and the Soviet Union would question the need to speed up the reduction of its conventional weapons in Europe. In his view, Germany’s joining NATO without progress on European security structures “could upset the balance of security, which would be unacceptable to the Soviet Union.”

Document 16

This memorandum from the Central Committee’s most senior expert on Germany sounds like a wake-up call for Gorbachev. Falin puts it in blunt terms: while Soviet European policy has fallen into inactivity and even “depression” after the March 18 elections in East Germany, and Gorbachev himself has let Kohl speed up the process of unification, his compromises on Germany in NATO can only lead to the slipping away of his main goal for Europe – the common European home. “Summing up the past six months, one has to conclude that the ‘common European home,’ which used to be a concrete task the countries of the continent were starting to implement, is now turning into a mirage.” While the West is sweet-talking Gorbachev into accepting German unification in NATO, Falin notes (correctly) that “the Western states are already violating the consensus principle by making preliminary agreements among themselves” regarding German unification and the future of Europe that do not include a “long phase of constructive development.” He notes the West’s “intensive cultivation of not only NATO but also our Warsaw Pact allies” with the goal to isolate the USSR in the Two-Plus-Four and CSCE framework.

He further comments that reasonable voices are no longer heard: “Genscher from time to time continues to discuss accelerating the movement toward European collective security with the ‘dissolving of NATO and WTO into it.’ ... But very few people … hear Genscher.” Falin proposes using the Soviet Four-power rights to achieve a formal legally binding settlement equal to a peace treaty that would guarantee Soviet security interests as “our only chance to dock German unification with the pan-European process.” He also suggests using arms control negotiations in Vienna and Geneva as leverage if the West keeps taking advantage of Soviet flexibility. The memo suggests specific provisions for the final settlement with Germany, the negotiation of which would take a long time and provide a window for building European structures. But the main idea of the memo is to warn Gorbachev not to be naive about the intentions of his American partners: “The West is outplaying us, promising to respect the interests of the USSR, but in practice, step by step, separating us from ‘traditional Europe.’”

Document 17

George H. W. Bush Presidential Library, NSC Scowcroft Files, Box 91126, Folder “Gorbachev (Dobrynin) Sensitive 1989 – June 1990 [3]”

The secretary of state had just spent nearly four hours meeting with the Soviet foreign minister in Bonn on May 4, 1990, covering a range of issues but centering on the crisis in Lithuania and the negotiations over German unification. As in the February talks and throughout the year, Baker took pains to provide assurances to the Soviets about including them in the future of Europe. Baker reports, “I also used your speech and our recognition of the need to adapt NATO, politically and militarily, and to develop CSCE to reassure Shevardnadze that the process would not yield winners and losers. Instead, it would produce a new legitimate European structure – one that would be inclusive, not exclusive.” Shevardnadze’s response indicates that “our discussion of the new European architecture was compatible with much of their thinking, though their thinking was still being developed.” Baker relates that Shevardnadze “emphasized again the psychological difficulty they have – especially the Soviet public has – of accepting a unified Germany in NATO.” Astutely, Baker predicts that Gorbachev will not “take on this kind of an emotionally charged political issue now” and likely not until after the Party Congress in July.

Document 18

Gorbachev Foundation Archive, Fond 1, Opis 1.

This fascinating conversation covers a range of arms control issues in preparation for the Washington summit and includes extensive though inconclusive discussions of German unification and the tensions in the Baltics, particularly the standoff between Moscow and secessionist Lithuania. Gorbachev makes an impassioned attempt to persuade Baker that Germany should reunify outside of the main military blocs, in the context of the all-European process. Baker provides Gorbachev with nine points of assurance to prove that his position is being taken into account. Point eight is the most important for Gorbachev—that the United States is “making an effort in various forums to ultimately transform the CSCE into a permanent institution that would become an important cornerstone of a new Europe.”

This assurance notwithstanding, when Gorbachev mentions the need to build new security structures to replace the blocs, Baker lets slip a personal reaction that reveals much about the real U.S. position on the subject: “It’s nice to talk about pan-European security structures, the role of the CSCE. It is a wonderful dream, but just a dream. In the meantime, NATO exists. …” Gorbachev suggests that if the U.S. side insists on Germany in NATO, then he would “announce publicly that we want to join NATO too.” Shevardnadze goes further, offering a prophetic observation: “if united Germany becomes a member of NATO, it will blow up perestroika. Our people will not forgive us. People will say that we ended up the losers, not the winners.”

Document 19

Gorbachev felt that of all the Europeans, the French president was his closest ally in the construction of a post-Cold War Europe, because the Soviet leader believed Mitterrand shared his concept of the common European home and the idea of dissolving both military blocs in favor of new European security structures. And Mitterrand did share that view, to an extent. In this conversation, Gorbachev is still hoping to persuade his counterpart to join him in opposing German unification in NATO. Mitterrand is quite direct, telling Gorbachev that it is too late to fight this issue and that he would not give his support, because “if I say ‘no’ to Germany’s membership in NATO, I will become isolated from my Western partners.” However, Mitterrand suggests that Gorbachev demand “appropriate guarantees” from NATO. He speaks about the danger of isolating the Soviet Union in the new Europe and the need to “create security conditions for you, as well as European security as a whole. This was one of my guiding goals, particularly when I proposed my idea of creating a European confederation. It is similar to your concept of a common European home.”

In his recommendations to Gorbachev, Mitterrand is basically repeating the lines of the Falin memo (see Document 16). He says Gorbachev should strive for a formal settlement with Germany using his Four-power rights and use the leverage of conventions arms control negotiations: “You will not abandon such a trump card as disarmament negotiations.” He implies that NATO is not the key issue now and could be drowned out in further negotiations; rather, the important thing is to ensure Soviet participation in new European security system. He repeats that he is “personally in favor of gradually dismantling the military blocs.”

Gorbachev expresses his wariness and suspicion about U.S. effort to “perpetuate NATO,” to “use NATO to create some sort of mechanism, an institution, a kind of directory for managing world affairs.” He tells Mitterrand about his concern that the U.S. is trying to attract East Europeans to NATO: “I told Baker: we are aware of your favorable attitude towards the intention expressed by a number of representatives of Eastern European countries to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact and subsequently join NATO.” What about the USSR joining?

Mitterrand agrees to support Gorbachev in his efforts to encourage pan-European processes and ensure that Soviet security interests are taken into account as long as he does not have to say “no” to the Germans. He says “I always told my NATO partners: make a commitment not to move NATO’s military formations from their current territory in the FRG to East Germany.”

Document 20

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, NSC Scowcroft Files, FOIA 2009-0275-S

True to his word, Mitterrand writes a letter to George Bush describing Gorbachev’s predicament on the issue of German unification in NATO, calling it genuine, not “fake or tactical.” He warns the American president against doing it as a fait accompli without Gorbachev’s consent implying that Gorbachev might retaliate on arms control (exactly what Mitterrand himself – and Falin earlier – suggested in his conversation). Mitterrand argues in favor of a formal “peace settlement in International law,” and informs Bush that in his conversation with Gorbachev he “indicated that, on the Western side, we would certainly not refuse to detail the guarantees that he would have a right to expect for his country’s security.” Mitterrand thinks that “we must try to dispel Mr. Gorbatchev’s worries,” and offers to present “ a number of proposals” about such guarantees when he and Bush meet in person.

Document 21

Gorbachev Foundation Archive, Moscow, Fond 1, opis 1.[13]

In this famous “two anchor” discussion, the U.S. and Soviet delegations deliberate over the process of German unification and especially the issue of a united Germany joining NATO. Bush tries to persuade his counterpart to reconsider his fears of Germany based on the past, and to encourage him to trust the new democratic Germany. The U.S. president says, “Believe me, we are not pushing Germany towards unification, and it is not us who determines the pace of this process. And of course, we have no intention, even in our thoughts, to harm the Soviet Union in any fashion. That is why we are speaking in favor of German unification in NATO without ignoring the wider context of the CSCE, taking the traditional economic ties between the two German states into consideration. Such a model, in our view, corresponds to the Soviet interests as well.” Baker repeats the nine assurances made previously by the administration, including that the United States now agrees to support the pan-European process and transformation of NATO in order to remove the Soviet perception of threat. Gorbachev’s preferred position is Germany with one foot in both NATO and the Warsaw Pact—the “two anchors”—creating a kind of associated membership. Baker intervenes, saying that “the simultaneous obligations of one and the same country toward the WTO and NATO smack of schizophrenia.” After the U.S. president frames the issue in the context of the Helsinki agreement, Gorbachev proposes that the German people have the right to choose their alliance—which he in essence already affirmed to Kohl during their meeting in February 1990. Here, Gorbachev significantly exceeds his brief, and incurs the ire of other members of his delegation, especially the official with the German portfolio, Valentin Falin, and Marshal Sergey Akhromeyev. Gorbachev issues a key warning about the future: “if the Soviet people get an impression that we are disregarded in the German question, then all the positive processes in Europe, including the negotiations in Vienna [over conventional forces], would be in serious danger. This is not just bluffing. It is simply that the people will force us to stop and to look around.” It is a remarkable admission about domestic political pressures from the last Soviet leader.

Document 22

Margaret Thatcher visits Gorbachev right after he returns home from his summit with George Bush. Among many issues in the conversation, the center of gravity is on German unification and NATO, on which, Powell notes, Gorbachev’s “views were still evolving.” Rather than agreeing on German unification in NATO, Gorbachev talks about the need for NATO and the Warsaw pact to move closer together, from confrontation to cooperation to build a new Europe: “We must mould European structures so that they helped us find the common European home. Neither side must be afraid of unorthodox solutions.”

While Thatcher speaks against Gorbachev’s ideas short of full NATO membership for Germany and emphasizes the importance of a U.S. military presence in Europe, she also sees that “CSCE could provide the umbrella for all this, as well as being the forum which brought the Soviet Union fully into discussion about the future of Europe.” Gorbachev says he wants to “be completely frank with the Prime Minister” that if the processes were to become one-sided, “there could be a very difficult situation [and the] Soviet Union would feel its security in jeopardy.” Thatcher responds firmly that it was in nobody’s interest to put Soviet security in jeopardy: “we must find ways to give the Soviet Union confidence that its security would be assured.”

Document 23

This key conversation between Chancellor Kohl and President Gorbachev sets the final parameters for German unification. Kohl talks repeatedly about the new era of relations between a united Germany and the Soviet Union, and how this relationship would contribute to European stability and security. Gorbachev demands assurances on non-expansion of NATO: “we must talk about the nonproliferation of NATO military structures to the territory of the GDR, and maintaining Soviet troops there for a certain transition period.” The Soviet leader notes earlier in the conversation that NATO has already began transforming itself. For him, the pledge of NATO non-expansion to the territory of the GDR in spirit means that NATO would not take advantage of the Soviet willingness to compromise on Germany. He also demands that the status of Soviet troops in the GDR for the transition period be “regulated. It should not hang in the air, it needs a legal basis.” He hands Kohl Soviet considerations for a full-fledged Soviet-German treaty that would include such guarantees. He also wants assistance with relocating the troops and building housing for them. Kohl promises to do so as long as this assistance is not construed as “a program of German assistance to the Soviet Army.”

Talking about the future of Europe, Kohl alludes to NATO transformation: “We know what awaits NATO in the future, and I think you are now in the know as well.” Kohl also emphasizes that President Bush is aware and supportive of Soviet-German agreements and will play a key role in the building of the new Europe. Chernyaev sums up this meeting in his diary for July 15, 1990: “Today – Kohl. They are meeting at the Schechtel mansion on Alexei Tolstoy Street. Gorbachev confirms his agreement to unified Germany’s entry into NATO. Kohl is decisive and assertive. He leads a clean but tough game. And it is not the bait (loans) but the fact that it is pointless to resist here, it would go against the current of events, it would be contrary to the very realities that M.S. likes to refer to so much.”[14]

Document 24

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons ((https://bush41library.tamu.edu/)

President Bush reaches out to Gorbachev immediately after the Kohl-Gorbachev meetings in Moscow and the Caucasus retreat of Arkhyz, which settled German unification, leaving only the financial arrangements for resolution in September. Gorbachev had not only made the deal with Kohl, but he had also survived and triumphed at the 28th Congress of the CPSU in early July, the last in the history of the Soviet Party. Gorbachev describes this time as “perhaps the most difficult and important period in my political life.” The Congress subjected the party leader to scathing criticism from both conservative Communists and the democratic opposition. He managed to defend his program and win reelection as general secretary, but he had very little to show from his engagement with the West, especially after ceding so much ground on German unification.

While Gorbachev fought for his political life as Soviet leader, the Houston summit of the G-7 had debated ways to help perestroika, but because of U.S. opposition to credits or direct economic aid prior to the enactment of serious free-market reforms, no concrete assistance package was approved; the group went no further than to authorize “studies” by the IMF and World Bank. Gorbachev counters that given enough resources the USSR “could move to a market economy,” otherwise, the country “will have to rely more on state-regulated measures.” In this phone call, Bush expands on Kohl’s security assurances and reinforces the message from the London Declaration: “So what we tried to do was to take account of your concerns expressed to me and others, and we did it in the following ways: by our joint declaration on non-aggression; in our invitation to you to come to NATO; in our agreement to open NATO to regular diplomatic contact with your government and those of the Eastern European countries; and our offer on assurances on the future size of the armed forces of a united Germany – an issue I know you discussed with Helmut Kohl. We also fundamentally changed our military approach on conventional and nuclear forces. We conveyed the idea of an expanded, stronger CSCE with new institutions in which the USSR can share and be part of the new Europe.”

Document 25

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, NSC Condoleezza Rice Files, 1989-1990 Subject Files, Folder “Memcons and Telcons – USSR [1]”

Staffers in the European Bureau of the State Department wrote this document, practically a memcon, and addressed it to senior officials such as Robert Zoellick and Condoleezza Rice, based on notes taken by U.S. participants at the final ministerial session on German unification on September 12, 1990. The document features statements by all six ministers in the Two-Plus-Four process – Shevardnadze (the host), Baker, Hurd, Dumas, Genscher, and De Maiziere of the GDR – (much of which would be repeated in their press conferences after the event), along with the agreed text of the final treaty on German unification. The treaty codified what Bush had earlier offered to Gorbachev – “special military status” for the former GDR territory. At the last minute, British and American concerns that the language would restrict emergency NATO troop movements there forced the inclusion of a “minute” that left it up to the newly unified and sovereign Germany what the meaning of the word “deployed” should be. Kohl had committed to Gorbachev that only German NATO troops would be allowed on that territory after the Soviets left, and Germany stuck to that commitment, even though the “minute” was meant to allow other NATO troops to traverse or exercise there at least temporarily. Subsequently, Gorbachev aides such as Pavel Palazhshenko would point to the treaty language to argue that NATO expansion violated the “spirit” of this Final Settlement treaty.

Document 26

George H. W. Bush Presidential Library, NSC Heather Wilson Files, Box CF00293, Folder “NATO – Strategy (5)”

The Bush administration had created the “Ungroup” in 1989 to work around a series of personality conflicts at the assistant secretary level that had stalled the usual interagency process of policy development on arms control and strategic weapons. Members of the Ungroup, chaired by Arnold Kanter of the NSC, had the confidence of their bosses but not necessarily the concomitant formal title or official rank.[15] The Ungroup overlapped with a similarly ad hoc European Security Strategy Group, and this became the venue, soon after German unification was completed, for the discussion inside the Bush administration about the new NATO role in Europe and especially on NATO relations with countries of Eastern Europe. East European countries, still formally in the Warsaw Pact, but led by non-Communist governments, were interested in becoming full members of international community, looking to join the future European Union and potentially NATO.

This document, prepared for a discussion of NATO’s future by a Sub-Ungroup consisting of representatives of the NSC, State Department, Joint Chiefs and other agencies, posits that "[a] potential Soviet threat remains and constitutes one basic justification for the continuance of NATO.” At the same time, in the discussion of potential East European membership in NATO, the review suggests that “In the current environment, it is not in the best interest of NATO or of the U.S. that these states be granted full NATO membership and its security guarantees.” The United States does not “wish to organize an anti-Soviet coalition whose frontier is the Soviet border” – not least because of the negative impact this might have on reforms in the USSR. NATO liaison offices would do for the present time, the group concluded, but the relationship will develop in the future. In the absence of the Cold War confrontation, NATO “out of area” functions will have to be redefined.

Document 27

George H. W. Bush Presidential Library: NSC Philip Zelikow Files, Box CF01468, Folder “File 148 NATO Strategy Review No. 1 [3]”[16]

This concise memorandum comes from the State Department’s European Bureau as a cover note for briefing papers for a scheduled October 29, 1990 meeting on the issues of NATO expansion and European defense cooperation with NATO. Most important is the document’s summary of the internal debate within the Bush administration, primarily between the Defense Department (specifically the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Dick Cheney) and the State Department. On the issue of NATO expansion, OSD “wishes to leave the door ajar” while State “prefers simply to note that discussion of expanding membership is not on the agenda….” The Bush administration effectively adopts State’s view in its public statements, yet the Defense view would prevail in the next administration.

Document 28

Rodric Braithwaite personal diary (used by permission from the author)

British Ambassador Rodric Braithwaite was present for a number of the assurances given to Soviet leaders in 1990 and 1991 about NATO expansion. Here, Braithwaite in his diary describes a meeting between British Prime Minister John Major and Soviet military officials, led by Minister of Defense Marshal Dmitry Yazov. The meeting took place during Major’s visit to Moscow and right after his one-on-one with President Gorbachev. During the meeting with Major, Gorbachev had raised his concerns about the new NATO dynamics: “Against the background of favorable processes in Europe, I suddenly start receiving information that certain circles intend to go on further strengthening NATO as the main security instrument in Europe. Previously they talked about changing the nature of NATO, about transformation of the existing military-political blocs into pan-European structures and security mechanisms. And now suddenly again [they are talking about] a special peace-keeping role of NATO. They are talking again about NATO as the cornerstone. This does not sound complementary to the common European home that we have started to build.” Major responded: “I believe that your thoughts about the role of NATO in the current situation are the result of misunderstanding. We are not talking about strengthening of NATO. We are talking about the coordination of efforts that is already happening in Europe between NATO and the West European Union, which, as it is envisioned, would allow all members of the European Community to contribute to enhance [our] security.”[17] In the meeting with the military officials that followed, Marshal Yazov expressed his concerns about East European leaders’ interest in NATO membership. In the diary, Braithwaite writes: “Major assures him that nothing of the sort will happen.” Years later, quoting from the record of conversation in the British archives, Braithwaite recounts that Major replied to Yazov that he “did not himself foresee circumstances now or in the future where East European countries would become members of NATO.” Ambassador Braithwaite also quotes Foreign Minister Douglas Hurd as telling Soviet Foreign Minister Alexander Bessmertnykh on March 26, 1991, “there are no plans in NATO to include the countries of Eastern and Central Europe in NATO in one form or another.”[18]

Document 29

U.S. Department of Defense, FOIA release 2016, National Security Archive FOIA 20120941DOD109

These memcons from April 1991 provide the bookends for the “education of Vaclav Havel” on NATO (see Documents 12-1 and 12-2 above). U.S. Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz included these memcons in his report to the NSC and the State Department about his attendance at a conference in Prague on “The Future of European Security,” on April 24-27, 1991. During the conference Wolfowitz had separate meetings with Havel and Minister of Defense Dobrovsky. In the conversation with Havel, Wolfowitz thanks him for his statements about the importance of NATO and US troops in Europe. Havel informs him that Soviet Ambassador Kvitsinsky was in Prague negotiating a bilateral agreement, and the Soviets wanted the agreement to include a provision that Czechoslovakia would not join alliances hostile to the USSR. Wolfowitz advises both Havel and Dobrovsky not to enter into such agreements and to remind the Soviets about the provisions of the Helsinki Final Act that postulate freedom to join alliances of their choice. Havel states that for Czechoslovakia in the next 10 years that means NATO and the European Union.

In conversation with Dobrovsky, Wolfowitz remarks that “the very existence of NATO was in doubt a year ago,” but with U.S. leadership, and NATO allied (as well as united German) support, its importance for Europe is now understood, and the statements of East European leaders were important in this respect. Dobrovsky candidly describes the change in the Czechoslovak leadership’s position, “which had revised its views radically. At the beginning, President Havel had urged the dissolution of both the Warsaw Pact and NATO,” but then concluded that NATO should be maintained. “Off the record,” says Dobrovsky, “the CSFR was attracted to NATO because it ensured the U.S. presence in Europe.”

Document 30

State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF), Fond 10026, Opis 1

This document is important for describing the clear message in 1991 from the highest levels of NATO – Secretary General Manfred Woerner – that NATO expansion was not happening. The audience was a Russian Supreme Soviet delegation, which in this memo was reporting back to Boris Yeltsin (who in June had been elected president of the Russian republic, largest in the Soviet Union), but no doubt Gorbachev and his aides were hearing the same assurance at that time. The emerging Russian security establishment was already worried about the possibility of NATO expansion, so in June 1991 this delegation visited Brussels to meet NATO’s leadership, hear their views about the future of NATO, and share Russian concerns. Woerner had given a well-regarded speech in Brussels in May 1990 in which he argued: “The principal task of the next decade will be to build a new European security structure, to include the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact nations. The Soviet Union will have an important role to play in the construction of such a system. If you consider the current predicament of the Soviet Union, which has practically no allies left, then you can understand its justified wish not to be forced out of Europe.”

Now in mid-1991, Woerner responds to the Russians by stating that he personally and the NATO Council are both against expansion—“13 out of 16 NATO members share this point of view”—and that he will speak against Poland’s and Romania’s membership in NATO to those countries’ leaders as he has already done with leaders of Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Woerner emphasizes that “We should not allow […] the isolation of the USSR from the European community.” The Russian delegation warned that any strengthening or expanding of NATO could “seriously slow down democratic transformations” in Russia, and called on their NATO interlocutors to gradually decrease the military functions of the alliance. This memo on the Woerner conversation was written by three prominent reformers and close allies of Yeltsin—Sergey Stepashin (chairman of the Duma’s Security Committee and future deputy minister of Security and prime minister), Gen. Konstantin Kobets (future chief military inspector of Russia after he was the highest-ranking Soviet military officer to support Yeltsin during the August 1991 coup) and Gen. Dmitry Volkogonov (Yeltsin’s adviser on defense and security issues, future head of the U.S.-Russian Joint Commission on POW-MIA and prominent military historian).

NOTES

[1] See Robert Gates, University of Virginia, Miller Center Oral History, George H.W. Bush Presidency, July 24, 2000, p. 101)

[2] See Chapter 6, “The Malta Summit 1989,” in Svetlana Savranskaya and Thomas Blanton, The Last Superpower Summits (CEU Press, 2016), pp. 481-569. The comment about the Wall is on p. 538.

[3] For background, context, and consequences of the Tutzing speech, see Frank Elbe, “The Diplomatic Path to Germany Unity,” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 46 (Spring 2010), pp. 33-46. Elbe was Genscher’s chief of staff at the time.

[4] See Mark Kramer, “The Myth of a No-NATO-Enlargement Pledge to Russia,” The Washington Quarterly, April 2009, pp. 39-61.

[5] See Joshua R. Itkowitz Shifrinson, “Deal or No Deal? The End of the Cold War and the U.S. Offer to Limit NATO Expansion,” International Security, Spring 2016, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 7-44.

[6] See James Goldgeier, Not Whether But When: The U.S. Decision to Enlarge NATO (Brookings Institution Press, 1999); and James Goldgeier, “Promises Made, Promises Broken? What Yeltsin was told about NATO in 1993 and why it matters,” War On The Rocks, July 12, 2016.

[7] See also Svetlana Savranskaya, Thomas Blanton, and Vladislav Zubok, “Masterpieces of History”: The Peaceful End of the Cold War in Europe, 1989 (CEU Press, 2010), for extended discussion and documents on the early 1990 German unification negotiations.

[8] Genscher told Baker on February 2, 1990, that under his plan, “NATO would not extend its territorial coverage to the area of the GDR nor anywhere else in Eastern Europe.” Secretary of State to US Embassy Bonn, “Baker-Genscher Meeting February 2,” George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, NSC Kanter Files, Box CF00775, Folder “Germany-March 1990.” Cited by Joshua R. Itkowitz Shifrinson, “Deal or No Deal? The End of the Cold War and the U.S. Offer to Limit NATO Expansion,” International Security, Spring 2016, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 7-44.

[9] The previous version of this text said that Kohl was “caught up in a campaign finance corruption scandal that would end his political career”; however, that scandal did not erupt until 1999, after the September 1998 elections swept Kohl out of office. The authors are grateful to Prof. Dr. H.H. Jansen for the correction and his careful reading of the posting.

[10] See Andrei Grachev, Gorbachev’s Gamble(Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2008), pp. 157-158.

[11] For an insightful account of Bush's highly effective educational efforts with East European leaders including Havel – as well as allies – see Jeffrey A. Engel, When the World Seemed New: George H.W. Bush and the End of the Cold War (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017), pp. 353-359.

[12] See George H.W. Bush and Brent Scowcroft, A World Transformed (New York: Knopf, 1998), pp. 236, 243, 250.

[13] Published in English for the first time in Savranskaya and Blanton, The Last Superpower Summits (2016), pp. 664-676.

[14] Anatoly Chernyaev Diary, 1990, translated by Anna Melyakova and edited by Svetlana Savranskaya, pp. 41-42.

[15] See Michael Nelson and Barbara A. Perry, 41: Inside the Presidency of George H.W. Bush (Cornell University Press, 2014), pp. 94-95.

[16] The authors thank Josh Shifrinson for providing his copy of this document.

[17] See Memorandum of Conversation between Mikhail Gorbachev and John Major published in Mikhail Gorbachev, Sobranie Sochinenii, v. 24 (Moscow: Ves Mir, 2014), p. 346

[18] See Rodric Braithwaite, “NATO enlargement: Assurances and misunderstandings,” European Council on Foreign Relations, Commentary, 7 July 2016.