Brazil

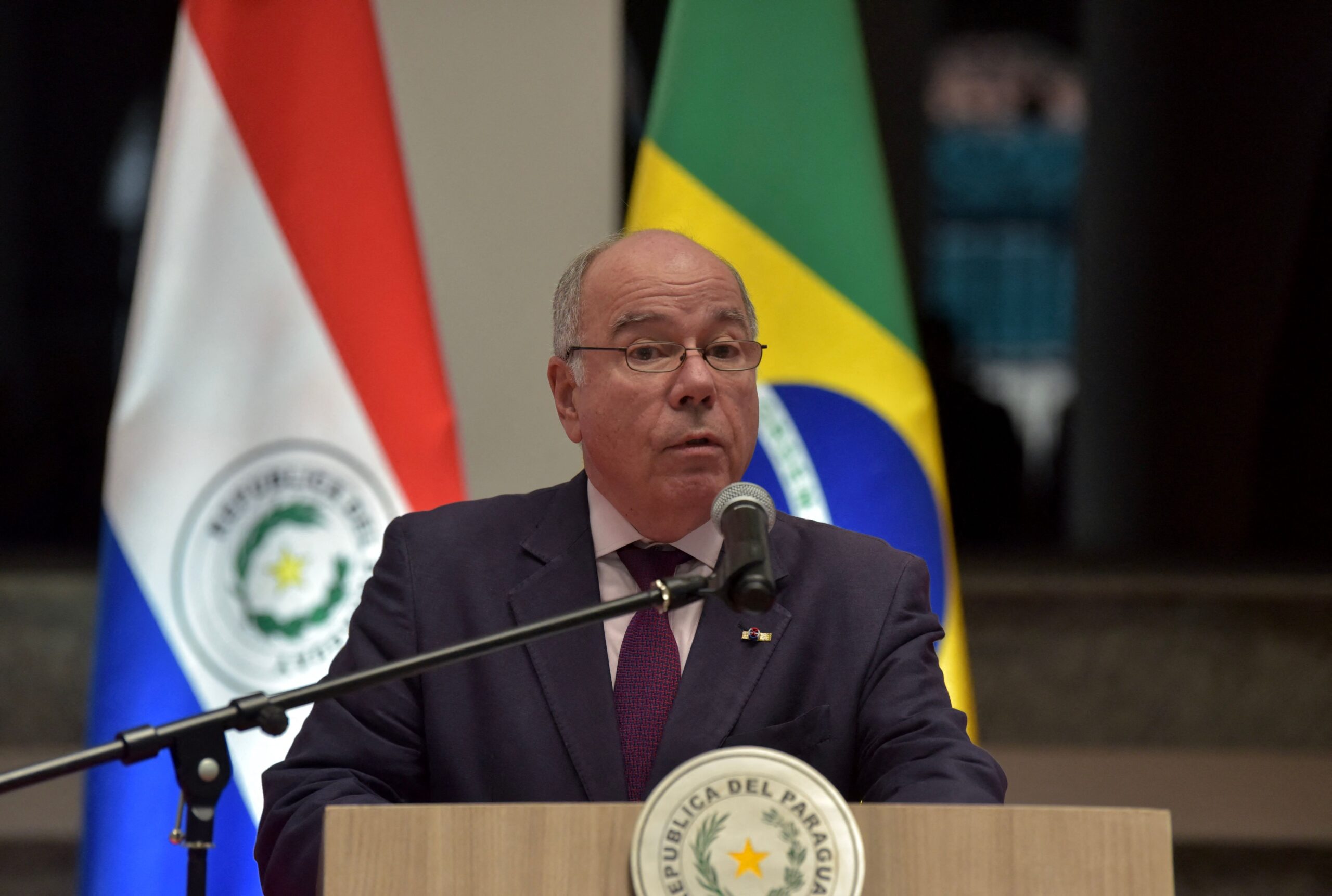

Q&A: Brazil’s Foreign Minister Mauro Vieira on the “Lula Doctrine”

This article is a preview of Americas Quarterly’s upcoming special report, “What Lula Means for Latin America,” to be published in April. (Ler em português)

BRASILIA — “Brazil is back,” declared President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva at an international conference shortly after his election. But what does that mean in practice for its relationships with the rest of Latin America, how it navigates the growing competition between China and the United States, and key flashpoints like the Ukraine war, Venezuela and Nicaragua?

Some of the answers will sound familiar to those who remember Lula’s first presidency, from 2003-10. But a lot since then has changed, both in Brazil and the world, which will lead to differences in foreign policy, Foreign Minister Mauro Vieira explained in an interview with AQ.

“Twenty years ago, China’s growth was visible, but now it is a superpower, without a doubt,” Vieira said. “In less than 20 years, China has become Brazil’s main trading partner—and not just Brazil, but many Latin American countries. So that changed the scenario a lot, and geopolitics have changed.”

This interview took place in Portuguese via Zoom on March 13. It has been translated to English and lightly edited for clarity and content.

Brian Winter: This may be a very American question, but here in the United States, we always talk about presidents’ doctrines – the Biden doctrine, the Bush doctrine. Is there a Lula doctrine?

Minister Mauro Vieira: I’d say the Lula doctrine is one of restoring Brazil’s image and its relationships—not just with our Latin American neighbors, but also restoring Brazil’s presence in the world, on all the different kinds of world stages, be they bilateral or multilateral. In the past four years, Brazil halted its diplomatic tradition of being a country that is open to all interlocutors, regardless of their ideological positions, and of maintaining contact, and negotiating and talking. I think that if there is a doctrine, that is it.

President Lula gave me very specific instructions. He gave a very powerful, very important speech during the Sharm el-Sheikh Climate Change Conference, where he said that “Brazil is back.” After he appointed me and after he took office, he said repeatedly that this is what matters most, that it should be known that Brazil is back to its diplomatic tradition. He told me to rebuild all the bridges and all channels of communication that had been destroyed.

BW: The world has changed a lot in the past 20 years since Lula’s first term. What are the most important differences between his foreign policy then and now?

MV: At the time, his foreign policy was referred to as ativa e altiva (active and assertive). That’s a phrase coined by the former Foreign Minister Celso Amorim, for whom I worked as chief of staff, and who represented very well this style of foreign policy in the first eight Lula years.

Of course, the world has changed a lot, in all ways, including media—information travels much more quickly—and geopolitics have also changed. Twenty years ago, China’s growth was visible, but now it is a superpower, without a doubt. In less than 20 years, China has become Brazil’s main trading partner—and not just Brazil, but many Latin American countries. So that changed the scenario a lot, and geopolitics have changed.

Now we have a war going on in Europe. And I think that global governance has also changed, because multilateral organizations, whether political or commercial, are very weakened, and they have lost their ability to act. From a commercial point of view, the World Trade Organization is paralyzed; it has lost relevance. And, at the same time, the situation of the United Nations is also worrying because we are witnessing the paralysis of its main body aimed at maintaining peace and security, which is the Security Council. The Security Council, with its 1945 format, is no longer reflected in today’s reality. And we are facing a major crisis in which its mechanisms, methods and composition do not allow the United Nations to play the fundamental role it should have—as Brazil’s argues it should, and as it did in the past.

Today there is a certain paralysis, to the detriment of world peace, to the detriment of better governance. So I think those are the big changes. And that’s where Brazil and President Lula’s foreign policy want to be active again, in promoting a discussion on global governance as well.

BW: The world has changed a lot. Brazil has also changed, especially in the last four years, as you mentioned. How do you see the efforts to restore Brazilian democracy following the events of recent months, especially the January 8 attacks in Brasilia? And these episodes, which represented an authoritarian risk for the country, similar to what we face here in the United States, do they have any point of intersection with Brazilian foreign policy? Or are they separate themes?

MV: Look, the issue of democracy in Brazil… I think that since 1964, when there was a break in the democratic order, which took 21 years [for democracy to be restored]… I think that with the restoration of democracy in Brazil and with the promulgation of the [1988] Constitution, we launched a young democracy, but a solid one, with solid instruments, dictated by the Constitution.

The events of January 8 were the result of clashes that have taken place in Brazilian society in recent years, since 2016, with the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff and then, in 2018, with the election of the last government, which represented a huge shift to the right. That changed Brazil’s position in terms of foreign policy, but it also changed domestic policies, emboldening a group that felt privileged and encouraged to even finance the events of January 8. I was in Brasília, and it was an unexpected and surprising event—to see that number of people, about 4000 people, arriving at the Praça dos Três Poderes [where the judicial, legislative and executive branches are located] and destroying the buildings… It is an unbelievable thing, which received not only ideological and political encouragement, but also important financial support from various sectors.

This comes from a part of Brazilian society that is not democratic and does not appreciate democratic values. There is no doubt that there was an election, that President Lula won.

So, now it’s a matter of investigating and clarifying what happened, who inspired this, who committed these highly illegal acts that could have really compromised Brazilian democracy. But I think society and the established authorities reacted quickly and everything was brought under control. On Sunday [when the attack happened], already at the beginning of the evening, everything was under control and many had been arrested. And that’s that, in short.

BW: And does this have any impact on Brazil’s foreign policy? For example, were the similarities between the risks faced by Brazil and the United States a fundamental part of President Lula’s [February 10] visit with President Biden in Washington?

MV: Undoubtedly, these are national issues, but also with repercussions on foreign policy. That night I received maybe 15 phone calls from foreign ministers from other countries, in which they expressed solidarity and support for Brazil and for Brazilian democratic institutions. Presidents Biden and Lula discussed the subject, referencing events in each country, and they made public comments on the need to strengthen democracies around the world.

I think that big countries like the United States, Brazil and others, can play an important role in the dissemination of democratic values and in reinforcing the importance of maintaining democracy and highlighting the gains of democracy. In the case of Brazil, it was thanks to the restoration of democracy since the promulgation of the Constitution of 1988 that we’ve had progressive governments, such as that of President Lula, which created conditions for economic growth and which benefited the population, lifting millions of people out of poverty, creating housing for people in need, healthcare systems and everything else.

This only happens in a democracy. Hence the importance of defending democracy, and any initiative to defend democracy internationally is very valid, because this way countries can develop and grow.

BW: Does the relative silence of the Lula government about dictatorships in Latin America, such as Nicaragua and Venezuela, in any way contradict this appreciation for democracy?

MV: No, because there is no silence.

The first time that there has been some movement on Nicaragua in the international scene inside a multilateral organization was in Geneva, at the Human Rights Council. [Editor’s note: On March 9, 54 countries including the United States, Chile, Peru and Colombia signed a statement urging the Ortega government to “release all political prisoners” and condemning the regime’s recent decision to revoke the citizenship of more than 300 Nicaraguans.] Brazil did not support [the statement], on the contrary. We wanted to make a separate statement, independent of that made by that group of nations. Because we wanted to make clear our position that there need to be changes, there need to be adjustments. Brazil wanted to first appeal to the multilateral mechanisms that are there and then discuss and exhaust all options before any other stronger measure, such as, for example, the adoption of sanctions, an element that was suggested throughout the debates.

That was the element that made us publish a separate declaration, referring to the need for dialogue with the [Ortega] government and relevant actors from Nicaraguan society. Unilateral sanctions, a measure many countries adopt, are illegal for Brazil. We can only apply sanctions that have been approved by the Security Council of the United Nations. So we could not, in principle, support a statement that didn’t make a reference to dialogue as a first step. And as it was the first opportunity [to debate this subject] in a multilateral forum, which is an institution that has the mechanisms to correct these points, and this was the first time that this discussion took place since President Lula took office, two and a half months ago, we wanted to make our position very clear.

BW: Does Brazil and the president have a role in possible peace negotiations between Ukraine and Russia?

MV: Look, President Lula has said this countless times… There is a lot of talk about Lula’s proposal… He didn’t make a concrete proposal, with goals to follow to reach peace. What he said is that he keeps hearing about war, about large amounts of resources being allocated for the purchase of arms, about destruction and death, and he doesn’t hear about peace. What he wants and what he has done is to call for us to start discussing, in some way, peace.

This is what is important, in the face of all the victims, all the destruction wreaked in the country. He also condemned the invasion of Ukraine, and commented on the worldwide effects of inflation, a threat to food security, the risk of this war lasting for many years, or even getting out of control, in a world where weapons are increasingly destructive and more lethal. So, it is with all this concern that he has made and will continue to make, calls for a sit-down, because we are absolutely convinced that it is not in the interest of either party to continue with this sad and deplorable war, without at least trying to find a negotiated solution.

Brazil is a pacifist country … that’s our diplomatic DNA. That’s what the president wants to tell the world.

BW: Many countries, especially in the global south, are adopting the idea, or the doctrine, of “active non-alignment” as a strategy for dealing with the growing competition between the United States and China. Ambassador Amorim, whom you mentioned, even wrote a chapter for a recent book on this idea. Does this concept basically summarize the Brazilian position on this issue?

MV: Yes, we don’t have an automatic alignment to either side. We have, on the contrary, excellent relations with the United States — in fact, next year we will celebrate 200 years of diplomatic relations with ambassadors in each country. And we also have important relations with China. What guides us is the national interest within a framework of multilateralism, of international law. Automatic alignments do not bring positive results and results that are beneficial to the national interest. There can be losses when there is an automatic and unjustifiable alignment. In fact, as there was during the last four years.

Photo by Evaristo Sa/AFP via Getty Images.

BW: There is a lot of talk about Latin American integration right now. There is ideological alignment between many governments in the region, but there is skepticism among some as to whether these ideas will translate into practical decisions, aside from meetings and the existence of blocs like CELAC and Unasur. Is there a concrete, practical agenda when it comes to regional integration? And what are the most important opportunities?

MV: There is no doubt that integration is a serious goal. In fact, Latin American integration is even in the Brazilian Constitution. And there are concrete examples, very concrete ones. The president visited Argentina and Uruguay. I just came back from Paraguay. President Lula will soon have a meeting with the president of Paraguay. These are the original partners of Mercosur. In these three cases, very specific measures and projects were agreed upon, pertaining to physical integration, for example, which is fundamental. We’ll soon announce them.

And these are projects that will benefit the road and rail infrastructure and river navigation in these countries, which will also have an immediate impact on trade: it lowers costs, it provides more security. It’s not just rhetoric. These are not projects that are starting now. We’re finalizing them, we put the final touches on them, and they are going to be implemented soon. And there are many others that could come.

CELAC is a place, it is a stage for discussions that can lead to concrete things. In addition, President Lula wants to review and update Unasur, which was indeed, differently from CELAC, a strong body, with concrete integration initiatives in many areas and which unfortunately was abandoned, but which we want to adapt and update, because it is also not the same world anymore. Mercosur integration translated to exponential growth in trade between our countries. Today we have important and significant trade for our economies, and without Mercosur, without an integration project, that would not happen.

BW: I mentioned this ideological alignment. Most governments, especially in South America, are left-wing, for all their differences. But it is possible that we will see a change of government in Argentina this year, for example. Is this ideological alignment important for Latin American relations, or is its importance overestimated?

MV: Look, the important thing is the national interest—and above all, the decisions of each country regarding integration with its neighbors. We cannot, under any circumstances, stop talking to any country, even more so to those with which we share a border. You know very well, as a Brazilianist, that we share 10 large borders with countries in the region. We cannot stop talking because this or that government has this or that ideological orientation. This is something that will not happen during President Lula’s government and that did not exist in Brazilian diplomatic tradition.

We will always talk to everyone. Regardless of ideological orientation. The national interest is above any difference of political position. So that’s what I can say, that’s what’s relevant, that’s what counts.

Tags: Brazil, Brazil's foreign policy, Lula