Um China Talk dedicado inteiramente à tentativa de golpe na Rússia. Muito interessante as comparações com fatos históricos do passado, mas eles nunca se aplicam inteiramente à situação presente. Putin vai se manter até que a situação material na Rússia se deteriore significativamente. Com o apoio da China de Xi Jinping, isso pode demorar.

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

The Russian Game

Jordan Schneider: Did Putin survive a coup this past weekend?

Kamil Galeev: More like an unsuccessful coup attempt. But even if were unsuccessful, it is still consequential. What many foreign observers may not know is that the Russian army has not really been a factor in “big politics” for most of the time.

An interesting feature of the Russian regime, including the Soviet period, is the exclusion of the army from big politics.

There are some exceptions, of course, especially during the transfer of power. The aftermath of the death of Stalin is one example.

But for the most part, the army has not been a factor in big politics. The influence of the military never converted into factional strife. What we have seen in the past few days is probably the most significant attempt to do so in the last seventy years.

Jordan Schneider: What were Prigozhin’s reasons for doing this?

Kamil Galeev: It looks very shady. Things like this usually look shady. Attempted or successful coups often have an element of 4D chess among the political leadership. Different forces try playing their own games.

Some observers in Russia, Eastern Europe, or Ukraine might write off what happened as staged events. But even if it were hypothetically staged, the consequences are real.

Consider the Kornilov putsch in 1917. It’s highly probable — some would say it’s almost certain — that the events in August or September 1917 showed signs of 4D chess by the provisional government headed by Aleksandr Kerensky. He at least somehow participated in it. In a sense, that coup attempt was orchestrated by the supreme leadership.

But even if it were orchestrated or staged, the consequences of the Kornilov putsch were still real. What we are going to see now will be very similar.

Jordan Schneider: So it doesn’t matter who orchestrated this — the end result is that Putin is weakened?

Kamil Galeev: Absolutely. Now, I could speculate that Prigozhin’s coup was a negotiation — not an internal negotiation but an external one with the West and especially the US. Putin might be saying, “If you continue pressuring me, some group of crazy gangsters and Nazis could take power and seize parts of our nuclear arsenal. Catastrophe will follow. Stop pressuring me.” That is pure speculation, but it is possible.

Another explanation might be that it was an attempt to scare the Russians themselves. In this sense, Putin might be saying, “If I fall down, you all go with me. Some horrible, absolutely unhinged rascals are going to take power. That will bring terrible consequences for everyone.” That is a nice explanation.

We could develop more speculations like this. They are absolutely possible. Some of them have an element of truth in them. It is plausible that some factions in power participated in orchestrating and staging what we saw.

But even if the coup were orchestrated or staged, the consequences are still real. We should keep in mind that complex, sophisticated 4D chess often does not work — or it works until it goes wrong.

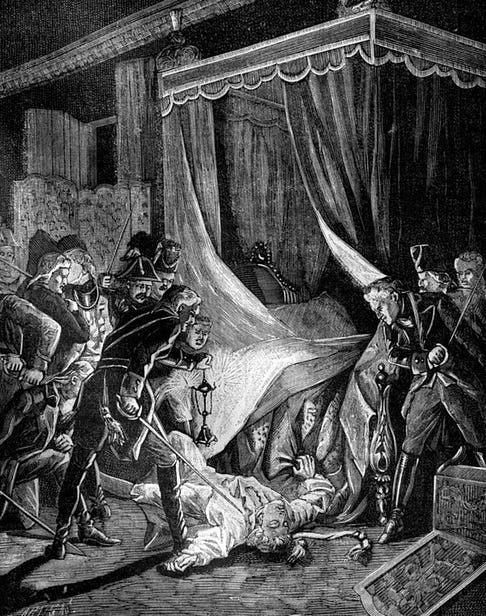

My favorite story is the 1801 assassination of the Emperor of Russia Paul I. He invited the general governor of St. Petersburg, Count Pahlen, and told him, “You see, they are preparing a coup attempt against me.” Pahlen said, “Yes, and I am participating in the coup so that I may collect information. Everything is under control.” “Great,” said the Emperor. He calmed down. He decided it was okay. Very soon he was killed.

Everything can go wrong for many reasons on the tactical level. On strategic level, it looks even more complicated.

A coup legitimizes the use of direct military force in the internal competition of factions — a dynamic they had previously tried to avoid.

The previous attempt to consolidate a base for a potential military coup was in Yeltsin’s era with General Lev Rokhlin. But that never got past the preparatory stage. What we have seen now is that you can start a coup and achieve significant results. That normalizes the use of the military for advancing the interests of your faction.

|

Barons and Courtiers

Jordan Schneider: When we last spoke, we discussed a world where Russia’s elites amass their own private armies to secure their spots in Russia’s future. It sounded far-fetched at the time, but the events of this past weekend suggest it is plausible. Now everyone in Russia knows mutinous action is possible. How does that change things?

Kamil Galeev: Who attempted this coup? It is not some independent baron or someone who rose without Putin. It’s basically a gangster who took power only because he was a member of the St. Petersburg gang, commissioned by Putin to do dirty jobs for him abroad in Ukraine. That’s really the only source of his power.

It’s very revealing because it’s not some regional interest group or provincial actors who made this move against the supreme power. It’s the supreme power’s own agents.

Niccolò Machiavelli made a distinction between two types of regimes. There are regimes that resemble France and those that resemble the Ottoman Empire.

The former are relatively easy to overthrow but difficult to control.France was a baronial regime with many dispersed barons. Aggressors could make alliances with these barons to overthrow the central power. But once you overthrew the central power, you couldn’t really rule the country because there were still lots of barons.

The Ottoman Empire was a very different type of regime. It didn’t have strong baronial factions like France did. It was more difficult to defeat the central power because aggressors could not ally with any independent powers. But once an aggressor took control, it was easy to hold.There were no independent powers to conspire against the aggressor.

People from baronial regimes are naturally shaped by them. They generally fail to comprehend other types of regimes, like one centered around a royal court.

America is a baronial regime. Russia, on the other hand, is ruled by courtiers. Many things happening in Russia are just unintelligible to Americans. The same goes for Russians looking at American politics.

For Russians, it is absolutely incomprehensible that the federal government in DC could have a major investment plan thwarted by a Senator from West Virginia. It’s unimaginable. Most Russian people — including people with resources, people with power — would not really believe that happened. There should have been some 4D chess within the federal government.

Russia does not have strong baronial factions. They exist but they are much weaker.

Russia is ruled by courtiers. When there is upheaval — when there is betrayal — it is not the barons who betray. They are weak. It is the courtiers. The Kremlin most fears not regional separatists, governors, or provincial interest groups. The Kremlin fears its own federal agents. No one else has the resources.

Après Putin, Le Déluge?

Jordan Schneider: How does the coup change the calculus for the Prigozhin-in-waiting — the inner-circle courtiers who have the independent means to do crazy things?

Kamil Galeev: We can only read the clues. We have seen that a military uprising is basically possible.

Most of the military and paramilitary structures, when faced with a coup, did nothing. It looks as though most of the military and paramilitary groups in the region where the attempted coup took place did not join Prigozhin. But they did not stand against Wagner either. They acted more like part of the landscape.

There was also quite a lot of public enthusiasm. On the streets of Rostov-on-Don, there was much cheering when the Wagner guys came, and there was a lot of booing when the police came in after.

The southern regions — cities like Belgorod, Rostov-on-Don, and Krasnodar — are really socially conservative and relatively well-off. They are very much pro-war — much more than the average Russian. They have traditionally been framed as the pro-Putin regions of Russia.

This shows that a simple “pro-Putin” versus “anti-Putin” dichotomy is just wrong when it comes to measuring overall Russian political attitudes. When another force presents itself as more brutish, patriotic, and militant, the people will cheer. They prefer some warlord like Prigozhin rather than Putin.

The people of southern Russia did not do anything to help or obstruct Prigozhin’s revolt either. They are absolutely willing to accept the intrusion of the military and paramilitary into political affairs. They’re basically waiting for it.

There’s a lot of discourse when people analyze electoral maps in Russia: “This region has traditionally voted for Putin, or that region has voted against him” — it’s not completely senseless or meaningless.

These analysts wrongly assume Russia has elections. It does not. It has never had elections, at least on a presidential level.

Elections have options. There is still some intrigue. There is still some anticipation, because America — the leading global power — has changed after many elections. The supreme executive power in Russia never changes as a result of elections. But elections still take place formally.

These are not elections. They are acclamations, as one might do for a Byzantine emperor. A ruler may succeed to power, but he still must receive his acclamation.

Yeltsin got his acclamations. Putin gets his all the time. But the crowd that would readily acclaim Putin would acclaim another guy, too.

Then there is also Putin’s standing within the circle of Russia’s ruling elite. He can say, explicitly or implicitly, that people hate the elites in general but they love him. He could say he is the only legitimate ruler and that the others enjoy their positions because of him. That would be a strong argument.

But that now looks like a much weaker argument than it did a few months ago.

Jordan Schneider: How has the attempted coup changed Putin’s options?

Kamil Galeev: His options are probably somewhat weaker now that other members of the ruling circle see that the willingness to acclaim Putin is not necessarily all about Putin.

People in general — especially the population in the regions deemed pro-Putin — are ready to cheer and acclaim pretty much everyone. It’s not some unique property of Putin which makes him irreplaceable for the existing elite.

It may not be a drastic change, but the experiment has been conducted.

Putin will probably be forced to repress those who were prone to supporting Wagner. The lords of the military and paramilitary, even if they did not outright support the mutiny, did not raise a finger either. That includes paratroopers, warrior cops, and the infantry.

The regime does not see all these fellows as absolutely loyal when facing an internal enemy. There will probably be some purges, though not necessarily bloody. We’re already seeing them on some of the more gruesome videos showing allegedly pro-Wagner troops getting their throats cut.

Marx wrote in his The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

Prigozhin’s coup basically looks more like the Kornilov putsch. There is a mutiny, it is suppressed, but the repressions and purges the regime conducts then weaken the regime, exposing it to further mutinies.

Jordan Schneider: What does all this mean for the war in Ukraine?

Kamil Galeev: Some Ukrainians, including those close to the regime in Kyiv, have been excessively optimistic. Many hoped the Russian regime would fall immediately and the war would stop. That did not happen, and it will not happen for a while.

But now that the taboo against military force in internal political games has been broken. The regime is weaker.

My personal prediction is we will see a second attempt — not necessarily by the same force, but quite probably by another force — within three to six months.

A Coup by Any Other Name

Jordan Schneider: How else might the lessons of the October Revolutionapply to today?

Kamil Galeev: Many people, including Putin himself, are drawing parallels to 1917. He compared Prigozhin’s coup attempt to 1917 when he said the mutiny was a “stab in the back.”

These parallels have been already normalized. Once the Bolsheviks took power and consolidated the regime, they made it their top priority to prevent any potential threats from the military. The Soviet Army was optimized for that purpose — so that it would not challenge the Communist Party’s rule.

Control of the Soviet Army was heavily centralized. Relatively few decisions are delegated. This hurt the army’s fighting efficiency, but also made it less of a political challenge.

It was successful. For many decades, the Communist Party ruled. There were no successful coup attempts. All were suppressed in their earliest stages, usually just at the point of talking.

Coups happen in relatively centralized regimes. If a regime is sufficiently decentralized, you don’t get a coup — you get a civil war. That’s quite different. Coups are usually executed by military and paramilitary forces. People are the source of legitimization.

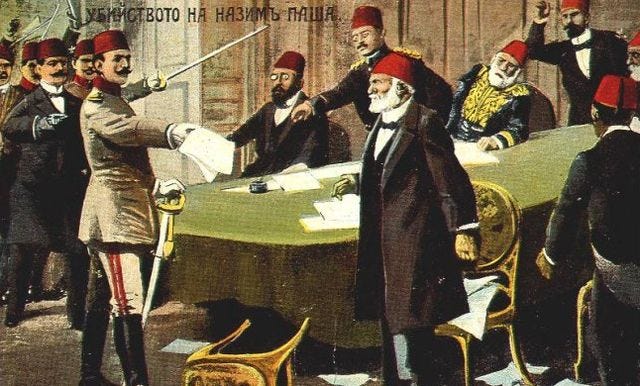

I love how Enver Pasha did it: during the Raid on the Sublime Porte in 1913, he came to the Grand Vizier Kâmil Pasha, the prime minister of the Ottoman Empire, and demanded he write a letter of resignation. So he started writing, “At the suggestion of the military.” Enver interrupted him, adding, “…and the people.”

The “people” are a source of legitimacy — but they are usually passive. They cheer for one force. They can also cheer for another.

Wish Upon a Falling Czar

Kamil Galeev: We’re probably seeing the end of the regime that naturally evolved from 1917.

That regime was revolutionary. It came by an abrupt, radical break with the past. The previous order was overthrown. The previous elites were persecuted and physically slaughtered. The Soviet regime was very different from what had existed previously and it was headed by different elites.

After that you just had evolution, not revolution. Lenin’s regime quite organically evolved into Stalin’s, and Stalin’s into Khrushchev’s, and so forth. Putin himself may have a personally negative opinion of Lenin and his regime — but Putin’s regime is ultimately the result of the gradual evolution of Lenin’s regime.

Quite probably after Putin, we’ll see a replacement, not an evolution, of his regime — something far exceeding what we saw in the 1990s. It wouldn’t be so much the fall of Putin as the replacement of elites in Russia on a gigantic scale.

Jordan Schneider: Why do you believe that whatever happens next will be a much more radical transformation of the regime and not just a changing of the guard?

Kamil Galeev: Regimes fall. We do not usually foresee these falls before they happen. The anthropologist Alexei Yurchak wrote a book called Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. That’s what usually happens. It’s usually impossible to predict it exactly, but it will be easily explained retrospectively, which everyone will be doing once it happens.

When there is an interconnected group of families ruling for decades with relatively low social mobility, that makes a regime fragile. The low level of being selected out of the regime helps secure the positions of individual families or interest groups, but it makes the system as a whole much more brittle.

The Russian ruling regime would be more robust were it to enthusiastically remove its own members. For example, there are generals in Russia — generals of the army, police, FSB, and many other services. They used to have a maximum age for retirement, somewhere around sixty years of age. Then Putin raised it to sixty-five or thereabouts — then seventy, then eighty, and then he just abolished it all.

Putin is naturally a conservative person. He doesn’t want to experiment much. He doesn’t want to change his people. If he were retiring staff one by one and getting new people, the ruling circle would be more mixed-age.

But if you just refuse to do anything, you will have the same group of people in power until they die. Then they’ll be dying one by one very quickly. That is similar to what happened at the end of the USSR.

Jordan Schneider: How worried should I be for the future of humanity in that case?

Kamil Galeev: Many Russians believe the West and especially America conspired against Russia and are just plotting to devolve the country into microstates. These Russians never comprehend how scared most Americans — including most political analysts — are about that scenario.

I understand your concern. While I cannot cure you, it’s a completely sound perspective. Maybe it makes sense to prepare in case that happens.

Jordan Schneider: Any final thoughts on Russia’s future? What have we neglected?

Kamil Galeev: Look at how the US intelligence and military command evolves over time. They put much less focus on military production than they used to during the Cold War. These concerns probably peaked in the 1970s, and it’s been downhill since then.

As a result, the nuclear status of Russia is discussed as a given — grass is green, the sky is blue, the sun is yellow, and Russia is a nuclear power. But in most cases, Russia’s nuclear power status is not problematized at all.

Russia went through the post-Soviet collapse. It lost most of its machinery. It lost most of its supply chains for military production. How can it still maintain its weapons of mass destruction as well as its delivery systems? How can it even produce new weapons and delivery systems? The short answer is that Russia outsourced its production of industrial equipment. The US and its allies provided this. There are no other alternatives in the world.

Both the maintenance of the existing part of the weapons of mass destruction and of delivery systems and their placement now fully depend on the importation of industrial equipment. In this case, it’s mostly machine tools, components, and maintenance supplied by US allies. Almost no one is discussing this. It gets almost zero attention nowadays, and I don’t fully comprehend why.

Next up, a 4000-word conversation where Kamil and I discuss:

Prospects of nuclear war;

His advice for Biden, European leaders, and Putin’s courtiers;

Predictions on state stability;

The trajectory of Moscow's grip on the regions...