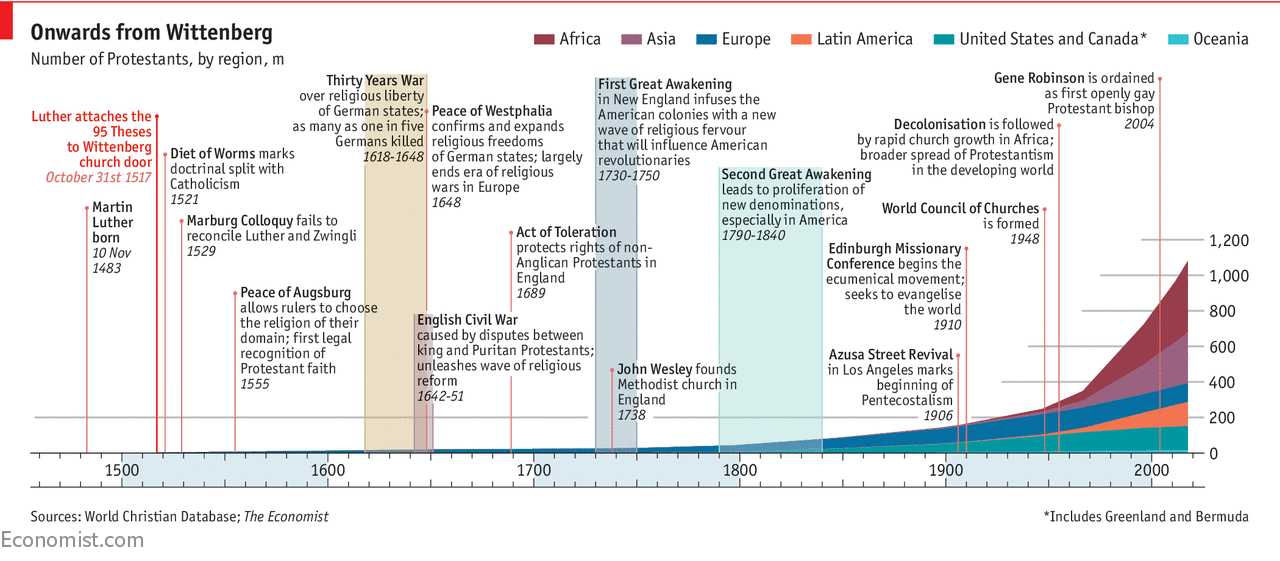

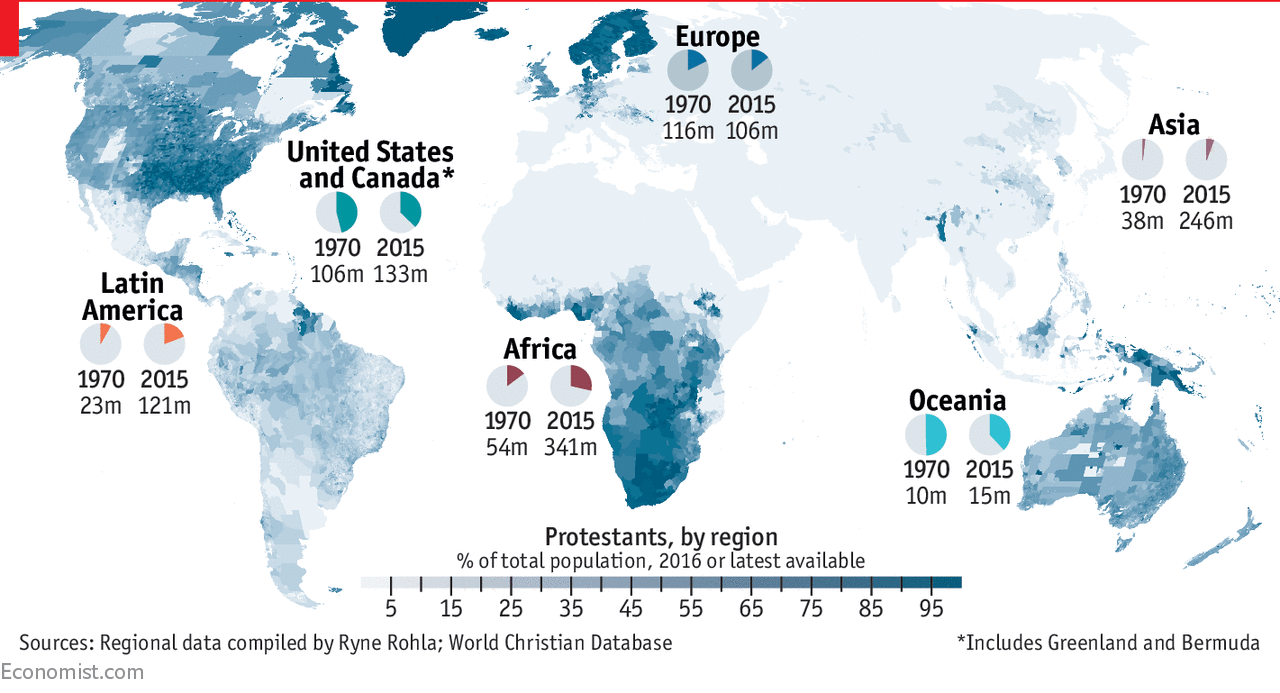

In Luther’s native Germany roughly half the Christians follow his denomination. But today Europe accounts for only 13% of the world’s Protestants. The faith’s home is the developing world. Nigeria has more than twice as many Protestants as Germany. More than 80m Chinese have embraced the faith in the past 40 years.

There are many ways to be a Protestant, from the quietist to the ecstatic. The fastest-growing varieties tend to be the evangelical ones, which emphasise the need for spiritual rebirth and Biblical authority. Among developing-world evangelicals, Pentecostals are dominant; their version of the faith is charismatic, in that it emphasises the “gifts” of the Holy Spirit, held to be a universally accessible and sustaining aspect of God. These gifts include healing, prophecy and glossolalia. According to the World Christian Database at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Massachusetts, Pentecostals and other evangelicals and charismatics account for 35% of Europe’s Protestants, 74% of America’s and 88% of those in developing countries. They make up more than half of the developing world’s Christians, and 10% of all people on Earth.

Changed lives change places. Almolonga’s Pentecostal believers have brought new energy to their town. Where once the prison was full and drunks slumped in the streets, there is now a buzz of activity. A secondary school opened in 2003; it sends some of its graduates, all members of the indigenous K’iché people, to national universities. “We want one of our students to work at NASA,” says Mr Riscajche’s son, Oscar, who chairs the school board.

Scholars have been surprised by the developing world’s Protestant boom. K.M. Panikkar, an Indian journalist, spoke for many when he predicted in the 1950s that Christianity would struggle in a post-colonial world. What might survive, he suggested, in both Protestant and Catholic forms, would be a more modern, liberal form of the faith. The Pentecostal expansion proved him quite wrong. Peter Berger of Boston University, a leading sociologist of religion (who died this summer), saw it as a key part of a wider “desecularisation” of the world.

To some extent, this growth of Pentecostalism among the global poor marks a loss of faith in political and secular creeds. As Mike Davies, an American writer and activist, put it in 2004, “Marx has yielded the historical stage to Mohammed and the Holy Ghost.” But it is worth noting that between 2000 and 2017 the 1.9% annual growth in the number of Muslims was mostly due to an expanding population, whereas a significant part of Pentecostalism’s expansion of 2.2% a year was due to conversion. Half of Latin America’s Protestants did not grow up in the faith.

Their emphasis on personal experience makes Pentecostalism and similar beliefs culturally malleable; their simplicity and ability to dispense with clergy gives them a nimbleness that suits people on the move. They tend to erode distinctions of faith based on ethnicity or birthplace. To Berger, that made this sort of Protestantism a modernising force. It is, he argued, “the only major religion which, at the core of its piety, insists on an act of personal decision.” Its mixture of distinctive individualism and strong, supportive communities, he wrote, makes it “a very powerful package indeed”.

For some sociologists, such ideas evoke the ghost of Max Weber, whose book, “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism”, published in 1905, posited that modern capitalism was the unintended consequence of an “inner-worldly asceticism” in early modern Protestantism. Such people made money but did not spend it, creating a thrifty, hard-working, literate, self-denying citizenry who drove forward the economies of their countries.

Few economists these days put much stock in Weber’s views. They point out that there was plenty of proto-capitalism—in 13th-century Italian city-states, for instance—before the Reformation, and the development of its modern form was influenced by many other factors. Today the idea seems out of date: the borders that once ensured an overlap between national markets and economic moralities have given way to capital flows and a consumer culture in which unrestricted gratification seems to be the norm.

Yet some hear echoes of Weber’s ideas in Pentecostalism’s growing social influence. “In Guatemala the Pentecostal church is just about the only functioning organisation of civil society,” says Kevin O’Neill of the University of Toronto. Almost all the drug-rehabilitation centres in Guatemala City, of which there are more than 200, are run by Pentecostal volunteers. Throughout Latin America, there are hints of the faith’s socioeconomic impact. A recent study of Brazilian men by Joseph Potter of the University of Texas and others found that Protestant faith was associated with an increase in the earnings of male workers over a 30-year period, especially among less educated people of colour.

In Almolonga itself, in the first decade of this century, farmers on average earned twice as much as those in the next village, where Protestantism had not taken off. Sceptics attribute this to the more fertile soil or new methods of farming. But according to Berger, “Max Weber is alive and well and living in Guatemala.”

How a turbulent monk turned the world upside down

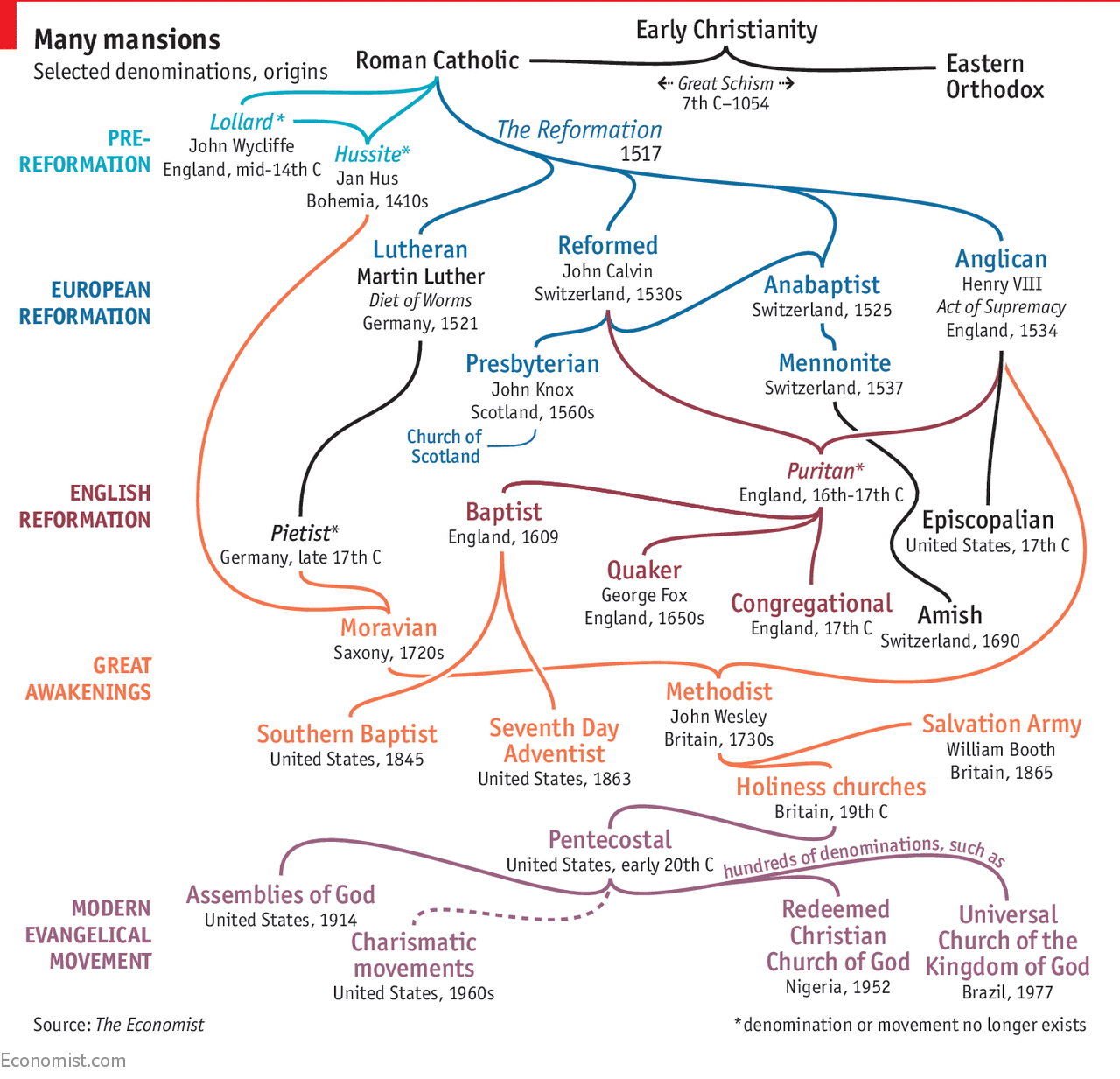

LUTHER was an accidental revolutionary. He was not trying to modernise his world but to save it. Had he become a lawyer, as his father wanted, Christendom—the European order organised by its rulers along lines largely set by the church—might have evolved very differently. The church might have reformed more from within; it might have fractured even more deeply than it did.

In 1521, at the Diet of Worms—an assembly called to discuss Luther’s teachings presided over by the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V—Luther was asked to recant his heretical view that men and women are saved by the grace of God alone. He replied that he could do so only if the Bible could be shown to prove him wrong. “My conscience is captive to the word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.” He may or may not have then said the words “Here I stand. I can do no other.” But that is the phrase that went on to define him and his faith.

Some who of those who took Luther’s Reformation further were better at systematising the faith. By the 1550s John Calvin had turned Geneva into a model Protestant city. Others were holier and shrewder. But few were such prolific agitators. Luther was responsible for more than a fifth of the entire output of pamphlets from the empire’s newfangled printing presses during the 1520s. “Every day it rains Luther books,” sighed one churchman. “Nothing else sells.”

Cantankerous and fiercely anti-Semitic, Luther was far from otherworldly. He abandoned his vows of chastity and entered an affectionate marriage, swore freely, drank eagerly and referred frequently to the state of his bowels. He was by no means a democrat, but his ideas had a huge political impact. In 1596 Andrew Melville, a Scottish Presbyterian, explained Luther’s doctrine of the “two kingdoms” to his king, James VI. In one kingdom James was a king, ruling in earthly pomp. But in the other, the kingdom of Christ, James was “not a king, nor a lord, nor a head, but a member”—the same as anyone else.

To begin with, Luther and other Protestants were keen that church and state should continue to be bound together—just with much clearer lines between their realms of authority. Keeping the state out of the church’s business meant clerics lost the power to suppress heretics by force. But Luther was content with that. He insisted that heresy should be fought from pulpits and in pamphlets, not by coercion. “Let the spirits collide,” he wrote. “If meanwhile some are led astray, all right, such is war.”

The result was a fissile movement. Protestantism’s first split was between the “magisterial” reformers, such as Luther and Calvin, who believed in national churches backed by state power, and the “radical” reformers, such as Anabaptists—men and women who wanted to form their own separate, perfect communities without waiting for the world to catch up with them. Those in the second group were often millenarians who believed in the imminent return of Jesus, John Milton’s “shortly expected King”. It is partly from this wing of the faith that the Pentecostal, evangelical and charismatic strands of modern Protestantism have grown.

The division in Protestantism had political repercussions. The German Peasants’ Revolt in 1524-25 was led by men who denounced serfdom as incompatible with Christian liberty and said they would desist only if they could be proved wrong on Biblical grounds. Luther was shocked at what he had unleashed, penning a pamphlet entitled “Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants”. But it was too late. The sects would not do as they were told. If God had spoken to them directly through his word, what was there to fear from kings and bishops?

Though the magisterial reformation triumphed in the transformation of northern European establishments from Catholic to Protestant, it was the longer-term triumph of the radical reformation that arguably had the deepest effects, in northern Europe and elsewhere. The new Protestant sects’ insistence that they be free to practise their faith did not extend to others—notably Catholics—seeking to practise theirs. But it did open up some space for the toleration and freedom of conscience that eventually helped create the principle of limited government. Milton’s “Areopagitica” of 1644 urged freedom of thought and freedom to publish. Uncensored printing offered the possibility of choice, ending the state church’s monopoly on opinion-forming.

Protestant toleration was good for business, too. The Calvinist Netherlands of the late 16th century became the world’s richest society as Huguenots, Jews and other hard-working refugees from Catholic lands flooded in. “The really radical twist that Protestantism added was the idea of human spiritual equality having a political consequence,” says Alec Ryrie of Durham University, author of “Protestants”, the best recent history of the faith.

This played out in the aftermath of the English civil war when religious groups such as the Diggers and the Levellers demanded universal male suffrage and common ownership of the land. In 1647 one of them, Thomas Rainsborough, said in the Putney debates with Oliver Cromwell, the Puritan who had led parliament, that “The poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under.” The Diggers were dispersed, but the idea that equality before God implied full democracy took root.

If people were to find Bible-based salvation independent of the clergy, literacy was indispensable. By 1760 about 60% of England’s men, and 40% of its women, were able to read. Protestant education provided opportunities for social mobility, improved the status of women and fostered economic growth. Elie Halévy, an influential early 20th-century French historian, believed that Methodism helped 18th-century England avoid a revolution of the sort that later befell France by educating the lower classes and bringing about social reform. This admiration was not universal: Britain’s pioneering Marxist historian of the working class, E.P. Thompson, considered Methodism to be a “ritual form of psychic masturbation”.

Like Roman Catholics, Protestants sought to bring their faith to other peoples, too. The motives for this were mixed, the respect for indigenous cultures often scant and frequently nonexistent and some of the results disastrous. That said, Robert Woodberry of Baylor University in Texas has mounted statistical arguments that former colonies where evangelical (what he calls “conversionary”) Protestant missionaries were active have become more democratic. He attributes this to mass education, religious liberty and a legacy of voluntarism.

In the colonies and Europe alike, Protestant Christianity brought bloodshed and persecution aplenty. Protestants and Catholics burned each other at the stake. During the Thirty Years War, fought mainly between Protestant and Catholic states, 8m people died. Britain, with its established Protestant church, did more than any other country to build up the trade that shipped some 12m people across the Atlantic in chains; Protestant America whipped the slaves thus delivered to work. In the 20th century the apolitical attitude inherent in Luther’s “two kingdoms” approach led German Protestants to believe they should not interfere with the state even when power fell into Nazi hands. Many were “either complicit or indifferent as unimaginable crimes were committed around them”, says Mr Ryrie.

Throughout, Protestants had an almost comical capacity for hypocrisy of all kinds. It could be seen not just in their vices, but also their virtues—particularly a rather selective toleration. The respect for their religious rights that 16th-century Mennonites demanded from the Dutch Republic was not extended to dissenters within their own ranks. By 1600 there were at least six Mennonite groups in the country. They hated each other with a passion.

How far from the tree can the fruits of the spirit fall?

PROTESTANTISM’S fissiparous tendencies persist. When searching for Mr Riscajche’s church in Almolonga, the Evangelical Church of Calvary, your confused correspondent thought he had arrived when he discovered the Mount Calvary Church. Not at all the same thing, it turned out. Almolonga, small though it is, has at least a dozen Pentecostal churches. But if the individual congregations for each are small, their cumulative effect is not.

Until the 1970s Guatemala was a staunchly Catholic country. When Protestant aid agencies rushed in after a massive earthquake in 1976, the faith gained a substantial foothold. After the country’s bloody civil war ended in 1996 it spread as if unshackled. Guatemalans took to the faith for many reasons, says Virginia Garrard of the University of Texas, but upheaval had a lot to do with it. The civil war represented a definitive break with the past: when so much had been destroyed anyway, losing your Catholic heritage meant less. At a time of painful economic dislocation, people who felt that Catholicism and liberation theology had failed them turned to an aspirational faith that promised a new upward mobility. With a low bar to entry and almost no hierarchy, new Pentecostal churches matched the entrepreneurial spirit of the times.

The message has resonated elsewhere. In South Korea, the Protestantism that accompanied the country’s dizzying economic rise was an expression of Korean nationalism. In China, a modernising population is looking for a moral framework to go with its new mobility. Yang Fenggang of Purdue University predicts that there could be at least 160m Protestants in China by 2025. He expects the country will soon be home to more Protestants than America.

As in early modern Europe, women in developing countries have often been especially affected by Protestantism. Having studied churches in Colombia, Elizabeth Brusco, author of “The Reformation of Machismo”, was surprised to find that evangelicalism was a women’s movement “like Western feminism”, explaining that “it serves to reform gender roles in a way that enhances female status.” Male Colombian converts had previously spent up to 40% of their pay in bars and brothels; that money was redirected to the family, raising the living standards of women and children. Temperance helped employment, too. Scholars also argue that the voice this has given women helps consolidate democracy; Mr Martin sees parallels with England’s 19th-century Methodists.

More stable, economically active households and well-knit communities have undoubtedly made places like Almolonga more agreeable for most who live there. But what effect do they have on a grander scale? Can they remake not just villages but whole countries and their economies?

Pentecostals have traditionally been suspicious of politics as too “worldly” and of development work as too long-term. But in Guatemala and elsewhere some are now mobilising for social change. Witness a rap battle in a community hall in one of the areas of Guatemala City known as “red zones”. Teenagers take it in turns to get up on stage and rap against each other, with judges deciding who goes through to the next round. The event has been organised by Angel, a local man who joined one of the city’s notorious gangs when he was 14. By the age of 22, he had shot “a lot of people”, he says. When he found himself about to be executed by a rival gang, he called out to God for help; he escaped death and was born again. For the past ten years, in a typically Pentecostal bottom-up initiative, he has been saving kids from gangs.

As yet, it is hard to see a broader impact from these individual transformations. Guatemala remains poor and desperate. Many people do not vote or pay tax; only a tiny fraction of murder investigations lead to convictions. The country lags behind the rest of Latin America on many development indicators. “Guatemala tests the limits of religion as an agent of change,” says Kevin O’Neill of Toronto University. “It’s not that the religion is ineffectual. It has changed a lot in society. It’s just that it has not changed things measurable by the metrics we use, such as security, democracy and economy.”

Perhaps the sort of change that can be measured will arrive in due course. Guatemala’s history has left it poor and oligarchic. “Five percent of the population controls 85% of the wealth,” says Mr O’Neill. More than three-quarters of the cocaine from South America heading for the United States now passes through it; many gang members have been deported from Los Angeles. Any society, never mind one recovering from a 36-year civil war, would struggle. “Guatemala is like a 400lb man who has lost 100lb in weight. He is getting better, but he is still in a bad state,” says Ms Garrard, who first visited in 1979. She ascribes much of the progress to the churches.

But it may also be that there are limits to 21st-century Protestantism’s capacity for large-scale reform. For one thing, it is largely a faith at the margins of society. In the places where Protestantism made its clearest mark in early modern Europe it took root in the bourgeoisie, among people of influence. A classic example is William Wilberforce, a British politician whose legislation banning the slave trade stemmed from his evangelical beliefs. Moreover, northern Europe’s Protestants lived in countries that already had clear property rights and the rule of law. By contrast, Protestants in the developing world are often among the poorest members of society, living in places with endemic corruption.

The otherworldly nature of Pentecostalism does not help. Believing in imminent apocalypse militates against strong social engagement. The ship is sinking; rather than try to fix it, Pentecostals want to get as many people as possible into the lifeboats. “What Guatemala needs is tax reform, voter registration, microloans, community organising,” says Mr O’Neill. But “people are just sitting there praying.”

That is not entirely true. “We know we need to change the system,” says Cash Luna, pastor of Casa de Dios, one of Guatemala’s half-dozen megachurches. “We pay our taxes and we encourage our congregation to do the right thing,” he says. The church also tries to mediate in the city’s gang warfare (Angel is a member) and holds classes for policemen on how to engage better with the public. Pentecostals took part in the anti-corruption movement that brought down the country’s president in 2015. But Protestant involvement in Guatemalan politics has been messy, and plentiful compromises have dragged the faith into disrepute.

In many places they lean to the right. Efraín Ríos Montt, who took control of Guatemala in a coup in 1982—and thus became the country’s first Protestant leader—waged the civil war as a fierce anti-Communist. He was responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of people, 80% of them indigenous Mayans; for some, Protestantism became a survival strategy. At the same time many Nicaraguan evangelicals supported the left-wing Sandinista government. In Brazil many of the country’s new evangelicals supported Lula, a left-wing president, in the 2000s. The movement’s political engagement there has not gone well. One pastor talks of the problem being “a church without a tradition…and an incapacity to think Christianly about society.”

It might be argued that the faith has been politically more successful in opposition than in power. Protestant churches, in particular the historic denominations established by missionaries, were instrumental in apartheid’s downfall in South Africa. Similar stories abound. “In Kenya during the 1980s, when all opposition activity was banned, the leaders of the opposition were, in effect, churchmen,” says Paul Gifford, emeritus professor of religion at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

But there were Protestants on the other side, too: apartheid was underpinned by the Dutch Reformed Church. Besides, the time for such opposition has largely passed, and the churches that offered it have not themselves become more democratic. Their leaders, including Desmond Tutu, a South African clergyman and theologian, have admitted that they have not adapted as well as the less hierarchical Pentecostal churches to the post-apartheid order. “We knew what we were against,” says Mr Tutu. “It is not nearly so easy to say what we are for.”

Early Protestantism tended to play down possessions. Luther himself called worldly success a sign of God’s displeasure. The wealth observed by Weber was treated to some extent as an unintended consequence of its possessors’ Calvinist faith. But in the “prosperity Gospel”, a recent export from the United States, wealth is very much the intention. Many of the new generation of pastors tell their flocks that God does not want them to be poor.

In Africa, many Pentecostal churches are concerned with “this-worldly” victory, says Mr Gifford. In Nigeria congregations with names like the “Victory Bible Church” hang banners saying things like “Success is my Birthright”. One of Nigeria’s best known pastors, David Oyedepo, whose church has been attended by the country’s presidents, says that Christians must be rich. Such preachers suggest that “planting seeds” (giving money to the church) will bring a harvest of its own, and that wealth is proof of God’s love. God must love Mr Oyedepo a lot; the Nigerian press reports that he is worth more than $150m and owns four private jets.

What Protestants do best is protest

IN 1882 Friedrich Nietzsche, a philosopher raised in Saxony as the son of a Lutheran minister, declared that God was dead. The vibrant spiritual lives of billions would seem to give this the lie. But in 20th-century Europe, at least, there seemed to be some truth to it; and a fair bit of the blame, or credit, fell to the Reformation. In helping to shape the West, Protestantism sowed the seeds of its own destruction. In giving people space to believe what they wanted and choose what sort of life to lead, it allowed them to stop believing at all and choose something else. And it has not fought as hard to resist this trend as some faiths might. After all, the whole point of Protestantism is that, in Mr Ryrie’s words, “it values the personal and the private over the political and the public.”

One effect of European (and, to some extent, American) secularisation is that old religious divisions are healing. There is still sectarian prejudice in parts of Europe, but much less than there was. And Protestantism is also less distinct than it was. According to the Pew Research Centre, 46% of American Protestants say faith alone is needed to attain salvation—the basis of Luther’s stand—but more than half now believe that good deeds are needed, too.

Even in America, the proportion of Protestants is declining. Mainline, often more liberal, denominations fell from 18.1% to 14.7% between 2007 and 2014, according to the Pew Research Centre. The proportion of evangelicals dropped less drastically, from 26.3% to 25.4%. Meanwhile, the religiously unaffiliated rose from 16.1% to 22.8%. In future, churches “that disdain the corruption of public life and offer spiritual rather than political power may find that their message resonates most,” predicts Mr Ryrie. But the faith will no doubt continue to be used as a weapon in the culture wars.

As for the developing world, the growth of Protestantism in Africa and Latin America does not seem to be just a way-station on the road to secularisation. But nor does it yet look like something that will transform the economy or politics on a large scale. Its effects may be strong, but they may also be largely indirect.

In some places Protestantism may settle down, with Pentecostals perhaps shifting to more staid denominations—or, indeed, fading into secularism. Some Protestants have understood that when they become the dominant religion, their faith’s power—its here-I-stand refusal to accept orders from any source but God or conscience—tends to seep away.

The places where Protestantism is most alive and seems politically most salient—where its churches continue to argue about who is right and what the Bible means, issuing statements and counterstatements just as Luther did—are often those where it has retained its outsider status. The growth of evangelical faith in China, for example, is taking place in a context of disapproval from which it seems to draw strength. In 2015 Wang Yi, a leading pastor, issued his own 95 theses on “Reaffirming our Stance on the House Churches”—the congregations outside the control of the government. It reiterated the need for freedom of conscience and for house churches to be allowed their independence, while protesting against the distortion of scripture and attacking state-approved churches for collusion with the Communist Party authorities. Wherever overweening rulers clash with people demanding their right to religious freedom, Luther’s divisive, dynamic spirit will remain an inspiration for a long time to come.