BOOK ESSAY - SUMMER 2013

Hannah Arendt on Trial

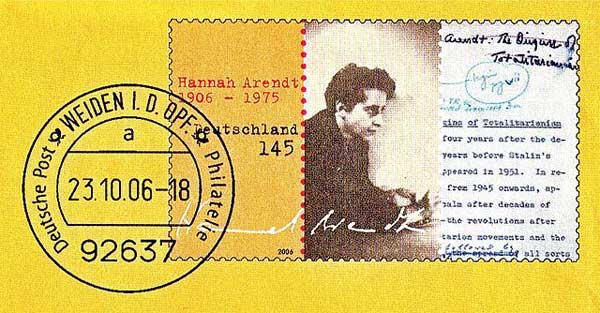

The 1963 publication of her “Eichmann in Jerusalem” sparked a debate that still rages over its author’s motivations

By Daniel Maier-Katkin and Nathan Stoltzfus |

The American Scholar, June 10, 2013

Fifty years ago, The

New Yorker published a series of articles that became one of the most

controversial books of the 20th century: Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in

Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. The articles dealt with

the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi SS officer who coordinated the logistics

of transporting millions of European Jews to their death during World War II.

Arendt portrayed Eichmann and other Nazi criminals not as hate-filled,

anti-Semitic monsters but as petty bureaucrats and spoke openly about the role

played by Jewish councils in the deportation and destruction of their own

people. Arendt’s central insight into what she called “the banality of

evil”—that great crimes can arise from mindless conformity and thoughtlessness

about the humanity of others—came paired with sharp criticism of Israeli

insensitivity to legitimate Palestinian claims and disregard for the rights of

minorities and neighbors.

Arendt suffered

ferocious personal attacks that continue today, 37 years after her death.

Criticism of her Eichmann book inevitably incorporates some variant of the

assertion that she felt herself to be more German than Jewish and was a

self-hating, anti-Semitic Jew—a strange charge against a woman who worked on

behalf of Jewish organizations most of her life. The 50-year battle over

Arendt’s reputation has pitted her defenders against those who would deflect

her criticism of Israel as anti-Jewish, thus turning people away from her ideas

about democratic pluralism and regional cooperation without having to discuss

them.

Soon after the

Eichmann pieces began to appear, civil rights activist Henry Schwarzschild

warned Arendt that Jewish organizations in New York were furiously planning a

campaign against her and that she should expect to be the object of great

debate and animosity.

Siegfried Moses, a

friend from Arendt’s youth who had immigrated to Israel and risen to the

position of state comptroller, sent a note to Arendt on behalf of the Council

of Jews from Germany, declaring war on her and her Eichmann book. Moses then

flew to Switzerland to meet with Arendt and demanded that she stop the book’s

publication. She refused, warning him that the intensity of criticism was

“going to make the book into a cause célèbre and thus embarrass the Jewish

community far beyond anything that she had said or could possibly do.” Indeed,

literary critic Irving Howe would describe the vitriolic public dispute that

ensued as “violent,” while novelist Mary McCarthy would liken it to a pogrom.

It began on March 11

with a memorandum distributed by the Anti-Defamation League alerting its

members to “Arendt’s defamatory conception of Jewish participation in the Nazi

Holocaust,” by which they meant her reporting that evidence at the trial showed

that leaders of Jewish communities across Europe had negotiated the orderly

demise of their communities with Eichmann. The ADL followed up with a pamphlet,

“Arendt Nonsense,” which called the Eichmann articles evil, glib, and trite.

On May 19, 1963, The

New York Times published a highly critical review of Eichmann

in Jerusalem by Michael A. Musmanno, a retired Navy rear admiral who

had served as a judge at the U.S. Nuremberg Military Tribunals and was then a

sitting justice on Pennsylvania’s supreme court. Musmanno had also appeared as

a witness for the prosecution at the Eichmann trial. In her book Arendt had

disparaged Musmanno’s testimony that Nazi foreign minister Joachim von

Ribbentrop told him at Nuremberg that Hitler’s madness had come about because

he had fallen under Eichmann’s influence. Even the prosecution knew this was a

fabrication. Musmanno wrote in the Times that Arendt was

motivated by “purely private prejudice. She attacks the State of Israel, its

laws and institutions, wholly unrelated to the Eichmann case.”

That summer New York

intellectuals weighed in. A review by playwright and critic Lionel Abel

in Partisan Review accused Arendt of having portrayed the

Nazis as more aesthetically appealing than their victims. Journalist Norman

Podhoretz’s review in Commentary concluded that Arendt had

exemplified “intellectual perversity [resulting] from the pursuit of brilliance

by a mind infatuated with its own agility and bent on generating dazzle.”

Zionist activist Marie Syrkin wrote in Dissent that Eichmann

was the only character who came out better in the book than he went in and

accused Arendt of manipulating the facts with “high-handed assurance.” Arendt

had published often in all three journals.

In July, when she came

home from Europe, where she had been traveling since the articles appeared,

Arendt wrote to a friend, the German philosopher Karl Jaspers, that her

“apartment was literally filled with unopened mail … about the Eichmann

business.” Much of it bordered on hate mail, like the letter from a woman in

New Jersey who began with a declaration that she had never read the Eichmann

book and “would never read such trash” and concluded with the hope that “the

ghosts of our six million martyrs haunt your bed at night.”

More measured

criticism came in a letter from Gershom Scholem, a friend from Arendt’s youth

and then a professor of Jewish mysticism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

He affirmed his “deep respect” for Arendt but characterized the tone of her

book as “heartless,” “flippant,” “sneering and malicious,” replacing balanced

judgment with a “demagogic will-to-overstatement.” He could never think of her,

he wrote, as anything other than “a daughter of our people” but admonished her

for insufficient Ahabath Israel, love of the Jewish people: “In

you, dear Hannah, as in so many intellectuals who come from the German Left, I

find little trace of this.”

Arendt replied that

she came not from the German Left but from the tradition of German philosophy

and that of course she was a daughter of the Jewish people and had never

claimed to be anything else: “I have always regarded my Jewishness as one of

the indisputable actual data of my life, and I have never had the wish to

change or disclaim facts of this kind. There is such a thing as basic gratitude

for everything that is as it is.” But you are quite right, she told him, in

what you say about Ahabath Israel. “I have never in my life ‘loved’

any people or collective—neither the German people, nor the French, nor the

American, nor the working class or anything of that sort. I indeed love ‘only’

my friends and the only kind of love I know of and believe in is the love of

persons.”

In the full flush of

the attack, Mary McCarthy stepped forward as Arendt’s champion. Writing in the

Winter 1964 issue of Partisan Review, she observed that the

hostile reviews and personal attacks on Arendt were written almost entirely by

Jews. She dismissed Lionel Abel’s assertion that Arendt made Eichmann

aesthetically palatable: “Reading her book, he liked Eichmann better than the

Jews who died in the crematoriums. Each to his own taste. It was not my

impression.”

Fevered discourse

continued to rage across the pages of Partisan Review’s next issue.

Marie Syrkin accused McCarthy of intellectual irresponsibility and ignorance,

and writer and historian Harold Weisberg characterized her defense of Arendt as

wholly lacking in charity and logic. Poet Robert Lowell countered that Arendt’s

only motive was a “heroic desire for truth.” Journalist and critic Dwight

Macdonald called Eichmann in Jerusalem a masterpiece of

historical journalism and defended McCarthy’s “brilliant” observation that the

split over the book was between Christians and Jews, especially

“organization-minded Jews.”

In 1965, Jacob

Robinson, an adviser to the prosecution in the Eichmann trial, published a

400-page denunciation of Arendt’s scholarship, And the Crooked Shall Be

Made Straight: The Eichmann Trial, The Jewish Catastrophe and Hannah Arendt’s

Narrative. With the assistance of teams of researchers in New York, London,

Paris, and Jerusalem, Robinson scoured Arendt’s book and found 400 “factual

errors,” including such minutiae as the misspelling of a first name. Some of

the things he listed, it turned out, were not errors at all. Nevertheless, an

essay by historian Walter Laqueur in The New York Review of Books asserted

that Arendt lacked the factual knowledge needed to make a scholarly

contribution. Laqueur characterized Robinson as “formidable,” an eminent

authority on international law, an erudite polymath with knowledge of many

languages and unrivalled mastery of sources. Robinson’s motivation for undertaking

a full-scale refutation of “Miss Arendt’s” flippant display of cleverness,

Laqueur wrote, was the natural “resentment felt by the professional against the

amateur.”

Arendt had been

reluctant to react publicly to the controversy, preferring to let her work

speak for itself. In January 1966, however, she responded, in The New York

Review of Books, to Laqueur’s essay. Laqueur, she wrote, was so

overwhelmed by Robinson’s “eminent authority” that he had failed to acquaint

himself with the facts. For a start, she had not written a narrative about the

Jewish catastrophe, but only a report about a trial. She criticized the

prosecution for repeatedly raising questions about why there had not been more

Jewish resistance during the Holocaust—a line of questioning she dismissed as

Israeli militarist propaganda. She also pointed out that Robinson was not a

historian but a lawyer who had published practically nothing prior to his book.

The honorific of “eminent authority” had been attached to him only after he joined

the chorus of critics attacking her. What is formidable about Robinson, Arendt

concluded, is that his words were amplified by the Israeli government with its

consulates, embassies, and missions throughout the world, along with the

American and World Jewish Congress, B’nai B’rith, and the ADL, in a coordinated

effort to characterize her book as a posthumous defense of Eichmann and her as

the evil person who wrote it.

Arendt worried that

the backlash against the Eichmann book had blown the controversy out of

proportion and that partially informed people would believe “all the nonsense”

critics were spouting. At the height of the scandal, however, Jaspers assured

her that she would emerge with her reputation intact: any fair-minded person

who read the Eichmann book would see her seriousness of purpose, honesty,

fundamental goodness, and passion for justice. “A time will come that you will

not live to see, when Jews will erect a monument to you in Israel, as they are

doing now for Spinoza,” he wrote. “They will proudly claim you as their own.”

Now, as the debate began to subside, Jaspers wrote that though she had suffered

greatly, the critical uproar was adding to her prestige.

Arendt wrote back that

she had been warmly received by the mostly Jewish students who had turned out

in substantial numbers for her lectures on politics at Yale, Columbia, Chicago,

and other universities. “The funny thing,” she told Jaspers, was that after

speaking her mind openly about “the formidable Mr. Robinson,” she was once

again “flooded with invitations from all the Jewish organizations to speak, to

appear at congresses, etc. And some of these invitations are coming from

organizations that I singled out to attack and named by name.”

In the next few years

she would collect a dozen honorary degrees from American universities and be

inducted into both the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the American

Academy of Arts and Sciences, which awarded her its Emerson-Thoreau Medal for

distinguished achievement in literature. In Denmark, where Jews had been

heroically protected during the Nazi occupation, Arendt in 1975 received the

Sonning Prize (worth the equivalent of roughly $200,000 today) for “commendable

work that benefits European culture.”

For a long moment,

which lasted another quarter-century after her death in 1975, Arendt had beaten

back her detractors, with her reputation intact. New Yorker editor

William Shawn wrote that Arendt’s death had removed “some counterweight to all

the world’s unreason and corruption,” that she had been “a moral and

intellectual force that went beyond category,” and that her influence “on

intellectuals, artists, and political people around the world was profound.”

More recently, though,

the battle over Arendt’s reputation and the value of her work, especially Eichmann

in Jerusalem, has been joined again, rekindled by evidence in Arendt’s

papers that as a young woman, she had a love affair with the German philosopher

Martin Heidegger. It was known that Arendt had been Heidegger’s student, but

the posthumous revelation of their romantic relationship by Arendt’s

biographer, Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, came as a bombshell.

Arendt and Heidegger

were lovers for about six months, beginning in November 1924. She was an

18-year-old philosophy student; he was 35, married with two children, and was

in something of a creative frenzy writing Being and Time, the

all but inscrutable masterpiece that established his position as an

existentialist. Arendt thought she was his muse. The love affair cooled by

summer, when Heidegger withdrew into family and professional life, and there

was less and less contact. Arendt appears to have suffered the bittersweet

longings of unrequited love.

What seemed a final

break between them occurred when the Nazis came to power in 1933. Arendt fled

Germany, and Heidegger very publicly joined the Nazi Party and was elevated to

the position of Rektor at Freiburg University. He resigned

after one year, having fired the Jewish faculty, disbanded the university

senate in favor of a Führer system of governance, and exhorted students to

military service, often ending his speeches, right arm stretched out and up in salute,

with “Heil Hitler,” repeated three times. After the war he downplayed the

significance of all this and told transparent lies about the past, claiming to

have done it all in an effort to protect the university.

Nevertheless, five

years after the war, Arendt reconciled with Heidegger. She was in Germany

directing a State Department project to preserve and distribute unclaimed

Jewish cultural property looted by the Nazis—mostly books and religious

artifacts—to synagogues and Jewish museums, libraries, and universities around

the world. Passing through Freiberg, she sent a note to Heidegger, who came to

see her. A lifelong friendship and affectionate correspondence ensued. After

the affair became public, Heidegger’s reputation as a Nazi seeped into the Eichmann

controversy, giving new shape to the old calumny that Arendt was a

pathologically self-hating Jew, whose opinions about Israel and Jewish politics

were not to be taken seriously.

Arendt’s latter-day

critics maintain that she was so blinded by schoolgirl love that she either

could not see what a bad man Heidegger was or did not care; that she so adored

him and the German intellectual tradition he represented that she was driven to

forgive him; that her affection for Heidegger and everything German explains

how she could distort Eichmann into something banal and display such shocking

insensitivity toward Jewish victims.

It is as if Arendt’s

detractors conflate Heidegger with Eichmann, a mass murderer whose execution

Arendt supported. Whatever his sins, Heidegger was not one of the leaders of

the Third Reich, nor was he involved in planning or executing war crimes or

crimes against humanity. He was, after 1934, an increasingly irrelevant

professor of philosophy. Despite his early enthusiasm for Nazism, there is

little evidence suggesting Heidigger was ever an anti-Semite. Granted, he was

never forthcoming about his past, not even in a final interview published by

prior agreement after his death. Still, he was not Adolf Eichmann.

Arendt understood the

distinction, once referring to Heidegger as a man who lied at the drop of a hat

in order to manage a situation. Heidegger nurtured fantasies of power as the

foremost Nazi intellectual and had grandiose ambitions to restore philosophy to

a state of grace not known since the Greeks, but his ignorance of the world,

Arendt concluded, prevented him from seeing that the Nazis were interested only

in people who thought as they did. In a public address honoring Heidegger on

his 80th birthday, Arendt referred to his Nazi time as a mistaken “escapade,”

spent primarily in “avoiding” (which implies willfully looking away from) the

reality “of the Gestapo’s secret rooms and the torture cells of the

concentration camps.”

Her critique was not

strong enough for Heidegger’s most severe critics, nor for Arendt’s. Heidegger

scholar Emmanuel Faye asserts that Heidegger’s texts reveal an inveterate Nazi

not only during the Hitler years but before and after as well. Faye finds that

even Being and Time, written 10 years before the Nazis came to

power, is so thick with veiled proto-Nazi messages that it should be shelved

next to Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

Literary critic Carlin

Romano, in a 2009 review of a book Faye wrote about Heidegger, laid the

philosopher’s guilt at Arendt’s feet, identifying her among the acolytes who

venerated the “pretentious old Black Forest babbler.” Journalist Ron Rosenbaum

adds that it will never be possible to think about Arendt or her

“intellectually toxic relationship” with Heidegger the same way again because

of her “lifelong romantic infatuation with the Nazi-sympathizing professor.” He

dismisses the “banality of evil” as the “most overused, misused, abused

pseudo-intellectual phrase in our language” and finds Arendt’s use of it

“deceitful,” “disingenuous,” and “utterly fraudulent” in relation to Eichmann,

concluding that the man responsible for the “logistics of the Final Solution”

simply could not be “a banal bureaucrat.”

Deborah

Lipstadt’s The Eichmann Trial (2011) concludes that Arendt was

just plain wrong about Eichmann. On the basis of “new” evidence that Eichmann

was a bully, braggart, and liar, Lipstadt proposes to supplant Arendt’s image

of the banal bureaucrat with a hate-filled, mad-dog, anti-Semitic monster.

Arendt was wrong,

Lipstadt declares, to think that Eichmann “did not really understand the

enterprise in which he was involved.” But this is certainly not what Arendt

meant when she concluded that the trial had been a “long course in human

wickedness [that] had taught us the lesson of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality

of evil.” Lipstadt’s insight into Arendt’s supposed misjudgment of Eichmann

is based on the reporting of a French journalist, Joseph Kessel, who was

present at the trial on a day when Arendt was not. When damaging depositions of

SS officers were read aloud, Kessel could detect “the passion and rage of the

true Eichmann” beneath the “hollow mask” of a bumbler that he held up to the

world.

Why does Lipstadt

think Arendt was unable to detect Eichmann’s true character? Because, she tells

us, Arendt was writing for only one person, the only person whose approval

mattered to her: Martin Heidegger. A more plausible understanding of

Heidegger’s significance in the history of the Eichmann book is that during her

first postwar encounter with her former mentor, in 1950, Arendt intuitively

recognized the banality of evil: Martin was still Martin. He had behaved

despicably, but she recognized his humanity and admired his genius. The

epiphany when she saw Eichmann a decade later was that, even at that level of

culpability (so far beyond Heidegger’s), the motives for direct participation

in mass murder were still fundamentally banal: not blood lust but ambition to

advance one’s career, to enjoy status and opportunity, to fulfill an oath of loyalty,

to be regarded as capable, a leader, a good fellow, perhaps to have a place in

history.

The more recent

battles over Arendt’s reputation and her criticism of Israeli policy and Jewish

politics have taken a desperate turn with their focus on her love affair with

Heidegger. Everything else about their relationship was known in 1963. The

assertion that Arendt was hard-hearted and uncaring is supported by nothing new

and is no stronger now than it was 50 years ago.

Arendt’s insight into

the banality of evil remains undiminished: human character is malleable, not

fixed; in the right circumstances masses of otherwise ordinary, decent,

law-abiding people can be transformed into collaborators and perpetrators of

reprehensible crimes against humanity.

Likewise, her

depiction of the Eichmann trial as political theater is still cogent. Arendt

was not alone in her criticism of the prosecution: the Israeli judges also

complained that the prosecutor relied on survivors’ inflammatory testimony

about the horrors of the Holocaust without showing a connection to the

defendant. What Arendt hoped to learn in Jerusalem was how Eichmann had done

his work, how the mass murders had been organized and implemented. Who had said

and done what with and to whom? But the prosecutor’s ambition was to capture

the imagination of Israeli youth and world Jewry with a retelling of the

suffering of the Holocaust.

Real justice, in

Arendt’s view, requires full disclosure, including self-disclosure, not only

retribution for Nazi crimes against humanity but also an effort to understand

how political systems can produce the complicity of perpetrators, bystanders,

and even victims. If evil is banal, it can turn up anywhere, even among

victims, even among Jews, even in Israel.

Permission

required for reprinting, reproducing, or other uses.

Daniel Maier-Katkin and Nathan Stoltzfus coauthored this article.

Maier-Katkin is the author of Stranger From Abroad: Hannah Arendt,

Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness. Stoltzfus is the author

of Resistance of the Heart: Intermarriage and the Rosenstrasse Protests

in Nazi Germany. Both are on the faculty at Florida State University.