Europe’s Russian Oil Ban Could Mean a New World Order for Energy

The effort could hurt Russia but could also help drive up already high oil prices, hurting the global economy and enriching energy companies.

Clifford Krauss

The New York Times – 2.6.2022

Houston - The European Union’s embargo on most Russian oil imports could deliver a fresh jolt to the world economy, propelling a realignment of global energy trading that leaves Russia economically weaker, gives China and India bargaining power and enriches producers like Saudi Arabia.

Europe, the United States and much of the rest of the world could suffer because oil prices, which have been marching higher for months, could climb further as Europe buys energy from more distant suppliers. European companies will have to scour the world for the grades of oil that its refineries can process as easily as Russian oil. There could even be sporadic shortages of certain fuels like diesel, which is crucial for trucks and agricultural equipment.

In effect, Europe is trading one unpredictable oil supplier — Russia — for unstable exporters in the Middle East.

Europe’s hunt for new oil supplies — and Russia’s quest to find new buyers of its oil — will leave no part of the world untouched, energy experts said. But figuring out the impact on each country or business is difficult because leaders, energy executives and traders will respond in varying ways.

China and India could be protected from some of the burden of higher oil prices because Russia is offering them discounted oil. In the last couple of months, Russia has become the second biggest oil supplier to India, leapfrogging other big producers like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. India has several large refineries that could earn rich profits by refining Russian oil into diesel and other fuels in high demand around the world.

Ultimately, Western leaders are aiming to weaken President Vladimir V. Putin’s ability to wreak havoc in Ukraine and elsewhere by denying him billions of dollars in energy sales. They hope that their moves will force Russian oil producers to shut down wells because the country does not have many places to store oil while it lines up new buyers. But the effort is perilous and could fail. If oil prices rise substantially, Russia’s overall oil revenue may not fall much.

Other oil producers like Saudi Arabia and Western oil companies like Exxon Mobil, BP, Shell and Chevron stand to do well simply because oil prices are higher. The flip side of that is that global consumers and businesses will have to pay more for every gallon of fuel and goods shipped in trucks and trains.

“It’s a historic, big deal,” said Robert McNally, a former energy adviser to President George W. Bush. “This will reshape not only commercial relationships but political and geopolitical ones as well.”

E.U. officials have yet to release all the details of their effort to squelch Russian oil exports but have said that those policies will go into effect over months. That is meant to give Europeans time to prepare, but it will also give Russia and its partners time to devise workarounds. Who will adapt better to the new reality is hard to know.

According to what European officials have said so far, the union will ban Russian tanker imports of crude oil and refined fuels like diesel, representing two-thirds of the continent’s purchases from Russia. The ban will be phased in over six months for crude and eight months for diesel and other refined fuels.

Daily business updates The latest coverage of business, markets and the economy, sent by email each weekday. Get it sent to your inbox.

In addition, Germany and Poland have pledged to stop importing oil from Russia by pipeline, which means Europeans could reduce Russian imports by 3.3 million barrels a day by the end of the year.

And the union has said that European companies will no longer be allowed to insure tankers carrying Russian oil anywhere. That ban will also be phased in over several months. Because many of the world’s largest insurers are based in Europe, that move could significantly raise the cost of shipping Russian energy, though insurers in China, India and Russia itself might now pick up some of that business.

Before the invasion of Ukraine, roughly half of Russia’s oil exports went to Europe, representing $10 billion in transactions a month. Sales of Russian oil to E.U. members have declined somewhat in the last few months, and those to the United States and Britain have been eliminated.

Some energy analysts said the new European effort could help untangle Europe from Russian energy and limit Mr. Putin’s political leverage over Western countries.

“There are many geopolitical repercussions,” said Meghan L. O’Sullivan, director of the geopolitics of energy project at Harvard’s Kennedy School. “The ban will draw the United States more deeply into the global energy economy and it will strengthen energy ties between Russia and China.”

Another hope of Western leaders is that their moves will reduce Russia’s position in the global energy industry. The idea is that despite its efforts to find new buyers in China, India and elsewhere, Russia will export less oil overall. As a result, Russian producers will need to shut wells, which they will not be able to easily restart because of the difficulties of drilling and producing oil in inhospitable Arctic fields.

Still, the new European policy was the product of compromises between countries that can easily replace Russian energy and countries like Hungary that can’t easily break their dependence on Moscow or are unwilling to do so. That is why 800,000 barrels a day of Russian oil that comes to Europe by pipeline was excluded from the embargo for now.

The Europeans also decided to phase in the restrictions on insuring Russian oil shipments because of the importance of the shipping industry to Greece and Cyprus.

Such compromises could undermine the effectiveness of the new European effort, some energy experts warned.

“Why wait six months?” said David Goldwyn, a top State Department energy official in the Obama administration. “As the sanctions are configured now, all that will happen is you will see more Russian crude and product flow to other destinations,” he said. But he added, “It’s a necessary first step.”

The Russia-Ukraine War and the Global Economy

A far-reaching conflict. Russia’s invasion on Ukraine has had a ripple effect across the globe, adding to the stock market’s woes. The conflict has caused?? dizzying spikes in gas prices and product shortages, and is pushing Europe to reconsider its reliance on Russian energy sources.

Global growth slows. The fallout from the war has hobbled efforts by major economies to recover from the pandemic, injecting new uncertainty and undermining economic confidence around the world. In the United States, gross domestic product, adjusted for inflation, fell 0.4 percent in the first quarter of 2022.

Energy prices rise. Oil and gas prices, already up as a result of the pandemic, have continued to increase since the beginning of the conflict. The sharpening of the confrontation has also forced countries in Europe and elsewhere to rethink their reliance on Russian energy and seek alternative sources.

Russia’s economy faces slowdown. Though pro-Ukraine countries continue to adopt sanctions against the Kremlin in response to its aggression, the Russian economy has avoided a crippling collapse for now thanks to capital controls and interest rate increases. But Russia’s central bank chief warned that the country is likely to face a steep economic downturn as its inventory of imported goods and parts runs low.

Trade barriers go up. The invasion of Ukraine has also unleashed a wave of protectionism as governments, desperate to secure goods for their citizens amid shortages and rising prices, erect new barriers to stop exports. But the restrictions are making the products more expensive and even harder to come by.

Food supplies come under pressure. The war has driven up the cost of food in East Africa, a region that depends greatly on exports of wheat, soybeans and barley from Russia and Ukraine and is already dealing with a severe drought. Amid dwindling supplies, supermarkets around the world have begun asking customers to limit their purchases of sunflower oil, of which Ukraine is a top exporter.

Prices of essential metals soar. The price of palladium, used in automotive exhaust systems and mobile phones, has been soaring amid fears that Russia, the world’s largest exporter of the metal, could be cut off from global markets. The price of nickel, another key Russian export, has also been rising.

Despite the oil embargo, Europe will likely remain reliant on Russian natural gas for some time, possibly years. That could preserve some of Mr. Putin’s leverage, especially if gas demand spikes during a cold winter. European leaders have fewer alternatives to Russian gas because the world’s other major suppliers of that fuel — the United States, Australia and Qatar — can’t quickly expand exports substantially.

Russia also has other cards to play, which could undermine the effectiveness of the European embargo.

China is a growing market for Russia. Connected mainly by pipelines that are near capacity, China increased its tanker shipments of Russian crude in recent months.

Saudi Arabia and Iran might lose from those increased Russian sales to China, and Middle Eastern sellers have been forced to reduce their prices to compete with the heavily discounted Russian crude.

Dr. O’Sullivan said that the relationship between Russia, Saudi Arabia and other members of the OPEC Plus alliance could become more complicated “as Moscow and Riyadh compete to build and maintain their market share in China.”

Even as energy commercial ties are scrambled, big oil producers like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have benefited overall from the war in Europe. Many European companies are now eager to buy more oil from the Middle East. Saudi oil export revenues are climbing and could set a record this year, according to Middle East Petroleum and Economic Publications, which tracks the industry, pushing the kingdom’s trade surplus to more than $250 billion.

India is another beneficiary because it has big refineries that can process Russian crude, turning it into diesel, some of which could end up in Europe even if the raw material came from Russia.

“India is becoming the de facto refining hub for Europe,” analysts at RBC Capital Markets said in a recent report.

But buying diesel from India will raise costs in Europe because it’s more expensive to ship fuel from India than to have it piped in from Russian refineries. “The unintended consequence is that Europe is effectively importing inflation to its own citizens,” the RBC analysts said.

India is getting about 600,000 barrels a day from Russia, up from 90,000 barrels a day last year when it was a relatively minor supplier. Russia is now India’s second biggest supplier after Iraq.

But India could find it difficult to keep buying from Russia if the European Union’s restrictions on European companies insuring Russian oil shipments raise costs too much.

“India is a winner,” said Helima Croft, RBC’s head of commodity strategy, “as long as they are not hit with secondary sanctions.”

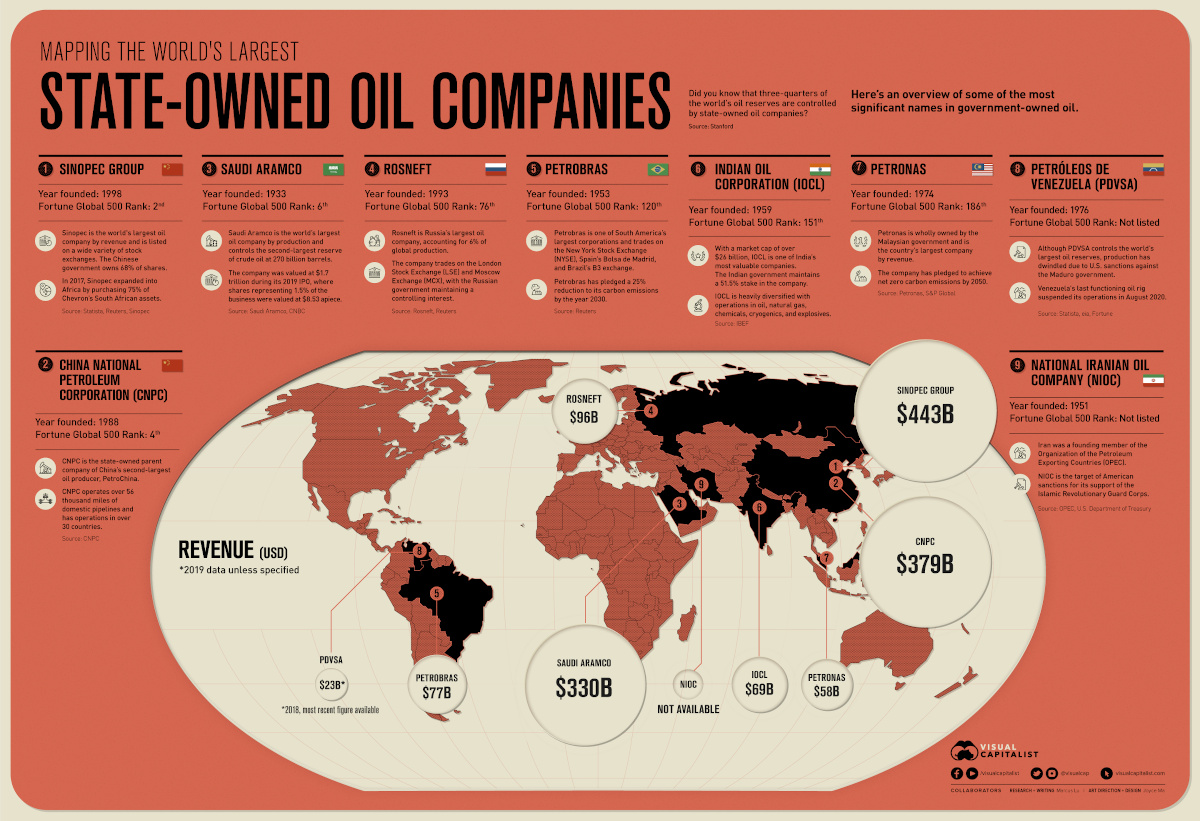

China

China Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia Russia

Russia Brazil

Brazil India

India Malaysia

Malaysia Iran

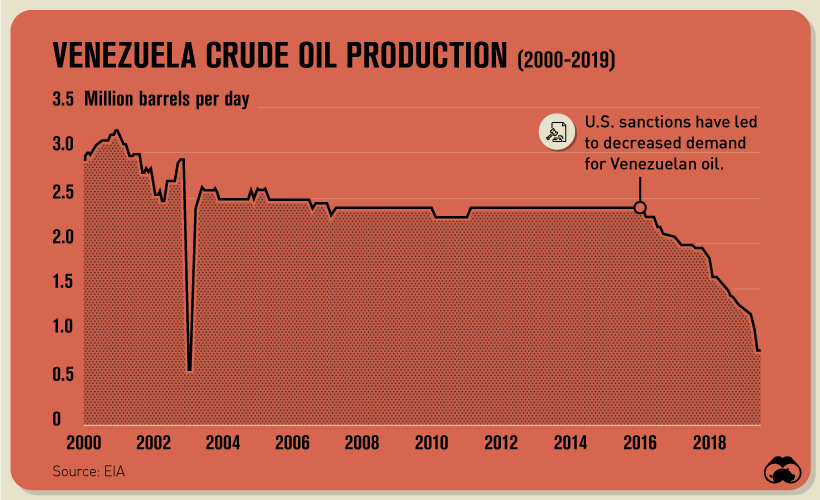

Iran Venezuela

Venezuela