What is the future of the dollar-based financial order in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Are we entering a new financial and economic regime? Will it be a regime of inflation? How safe are US Treasuries as a vehicle for investment?

A lot of folks are struggling with these questions right now. It has spawned a genre of future-orientated Finance-Fiction all of its own.

When I googled finance fiction, I discovered that since 2008, finance fictionand the finance novel has emerged as respectable genres of literature.

What I mean to refer to in using the terms is the less literary, more speculative variety of writing - by analysts and other authors of non-fiction - about possible future scenarios for the world economy and its financial system. To distinguish this less literary genre let me call it Fin-Fi for short, as in Sci-Fi or Cli(mate)-Fiction.

At the current moment, two lines of questions dominate these narratives.

One is the question of supply chains, which poses profound questions about the relationship between the monetary and the real economy.

The other is geopolitics and the power of the dollar.

With regard to both I am skeptical. My bet is that the current system has huge inertia and is tied down by gigantic network economies.

I discussed Eichengreen et al’s findings about diversification of reserve holdings away from the dollar in Chartbook 106.

I don’t find it convincing to claim that a greater use of Australian dollars or South Korean won in foreign exchange reserves amounts to a watering down of dollar hegemony. All these “alternatives” to the dollar are, in fact, underpinned by dollar swap lines.

In the last issue of Chartbook, I went back and forth with Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu of the FT’s Unhedged over Larry Fink’s comments about the Ukraine war and the end of globalization. I ended up unconvinced that Larry Fink was himself not in earnest. There is such a compulsion to cater to the demand for Fin-Fi right now that in his annual letter Fink could hardly avoid saying something. So he ended up saying something anodyne and incoherent.

Zoltan Pozsar’s writing on the theme, however, is in a different league. If Fin-Fi in the current moment has an H.G. Wells or a Jules Verne, it is Pozsar of Credit Suisse.

If Eichengreen and his co-authors demand attention because of the empirical depth of their work, what entices about Pozsar is his conceptual depth and idiosyncratic style. What sets Pozsar’s musings over the last two months apart is that he starts from a fundamental analysis of how money works.

In his latest must-read note, Pozsar starts with the framework for thinking about money offered by his intellectual mentor, the great Perry Mehrling.

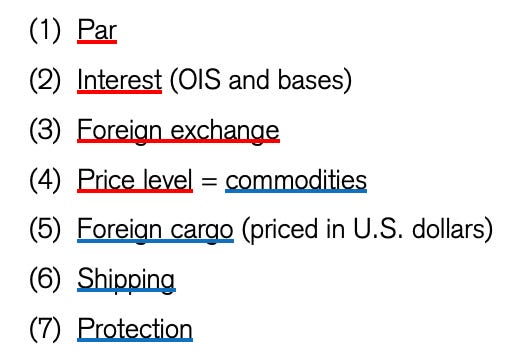

For Mehrling, money can be thought of as being situated in four different relationships, each calibrated by a price.

Par price refers to the price that you pay to exchange different types of money into each other - regular bank deposits for reserve deposits at the central bank, for instance. Claims that in good times are “as good as money”, will, in a crisis be exchangeable into central bank money only at a signifiant discount to par.

The interest rate is the price you pay to exchange money today for money at some other point in the future.

Foreign exchange is the price you pay to swap one currency into another.

The price level is the rate at which money exchanges for actual commodities.

Crises that play out in monetary domains (1), (2) and (3) are obviously within the reach of central banks. The central bank can ensure that assets trade with each other on stable and equal terms. It can manipulate interest rates and, to a degree, exchange rates. It can certainly ensure that markets continue to function for both credit and foreign exchange.

As Pozsar emphasizes, his perspective is that of a bond market analyst, so what concerns him is less whether the central bank can actually fix a particular exchange rate, but whether it has the tools, in a general sense, to intervene in that market and what implications that might have for government bonds. It is up to the market to haggle over particular exchange rates, or interest rate levels. If there are divergent perspectives on the proper price that can be hedged with derivatives of various kinds.

For someone coming from the monetary sphere, the bamboozling thing about the last few years is that central banks clearly do not have all the tools necessary to deal with shocks that originate on the supply side of the sphere of commodities and impact on the price level.

For decades the open secret has been that for all their talk about price stability, the one thing that central banks have not had to worry about is prices. Inflation was tamed. That no longer seems the case.

The problem first reared its ugly head during the COVID crisis and the ensuing supply chain problems. The war now adds the further dimension of national security to supply chain issues. Both factors push in an inflationary direction and they push from the “real side”, from the “supply side”, over which the central bank has precious little influence.

The importance of Pozsar’s latest note is that he expands Merhling’s money framework to explicitly address both the “real side” of the economy and its political frame.

What Pozsar then sets out to do is to map the seismic shocks the world economy is currently experiencing onto this list and to derive from that analysis a story about its likely future development.

To understand the drivers of his narrative we need to dig into his analytical framework a little more deeply.

The items on Pozsar’s seven-point list are conceptually and practically linked.

The real counterpart to the prices that we aggregate as “the price level”, are the commodities to which those prices are attached. Those commodities have an order that is more multi-dimensional than that of prices. Perhaps we ought to call it the “matrix of commodities”.

That matrix is geographically, nationally demarcated. So, the counterpart to foreign exchange is trade in foreign commodities.

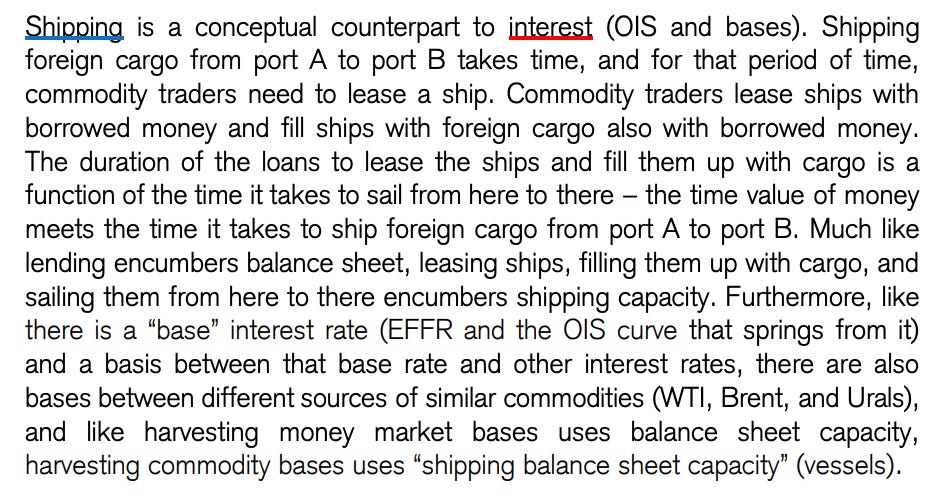

The counterpart to the trade-off between money now and money later that defines the rate of interest in Pozsar’s scheme, is the fact that moving commodities from one place to another takes time. So, in our supply-chain-obsessed world, shipping is the counterpart to interest. One of the pleasures of reading Pozsar is to follow him as he loses himself in detail, whether it be bond markets, the plumbing flow of shadow banking, or oil tankers.

Finally, if the exchange of one type of money for another (the question of the par price) as conceptualized by Mehrling, is essentially a question of where one is located in the hierarchy of money types, then it makes sense to think of the “real” counterpart to par as the question of protection i.e. your relationship to power. In extremis, will your transaction be protected by a “gunboat” or, more likely, a drone, or not?

The really interesting links in this analysis to my mind are the pairing of

(1) par and (7) protection

and (2) interest and (6) shipping.

Pairing par and protection allows us to bring politics and geopolitics seamlessly into the conversation about money. That is where the conversation about lender of last resort took off back in 2008. Holding American dollars or claims on the US tax payer in the form of Treasuries entitles you to a different degree of protection. So too does holding claims on the US banking system.

When the hierarchy of the dollar-based financial system is combined with foreign exchange (3) you end up back at the question of which countries have access to swap lines, the question that has preoccupied so many of us since 2008. Which fx claims get backed by an offer from the US Federal Reserve to swap them into dollars on demand?

This is why it matters that all the “minor” reserve currencies - Canadian, Australian, South Korean etc - discovered by Eichengreen and his co-authors are all covered by swap lines. Those commitments on the part of the Fed make those currencies equivalent to dollars in a crisis. This is the financial counterpart to America’s Indo-Pacific security system.

The really interesting bit from an economic point of view is the link that Pozsar teases out between (2) interest and (6) shipping and the implications that connection has for money and finance in the current moment.

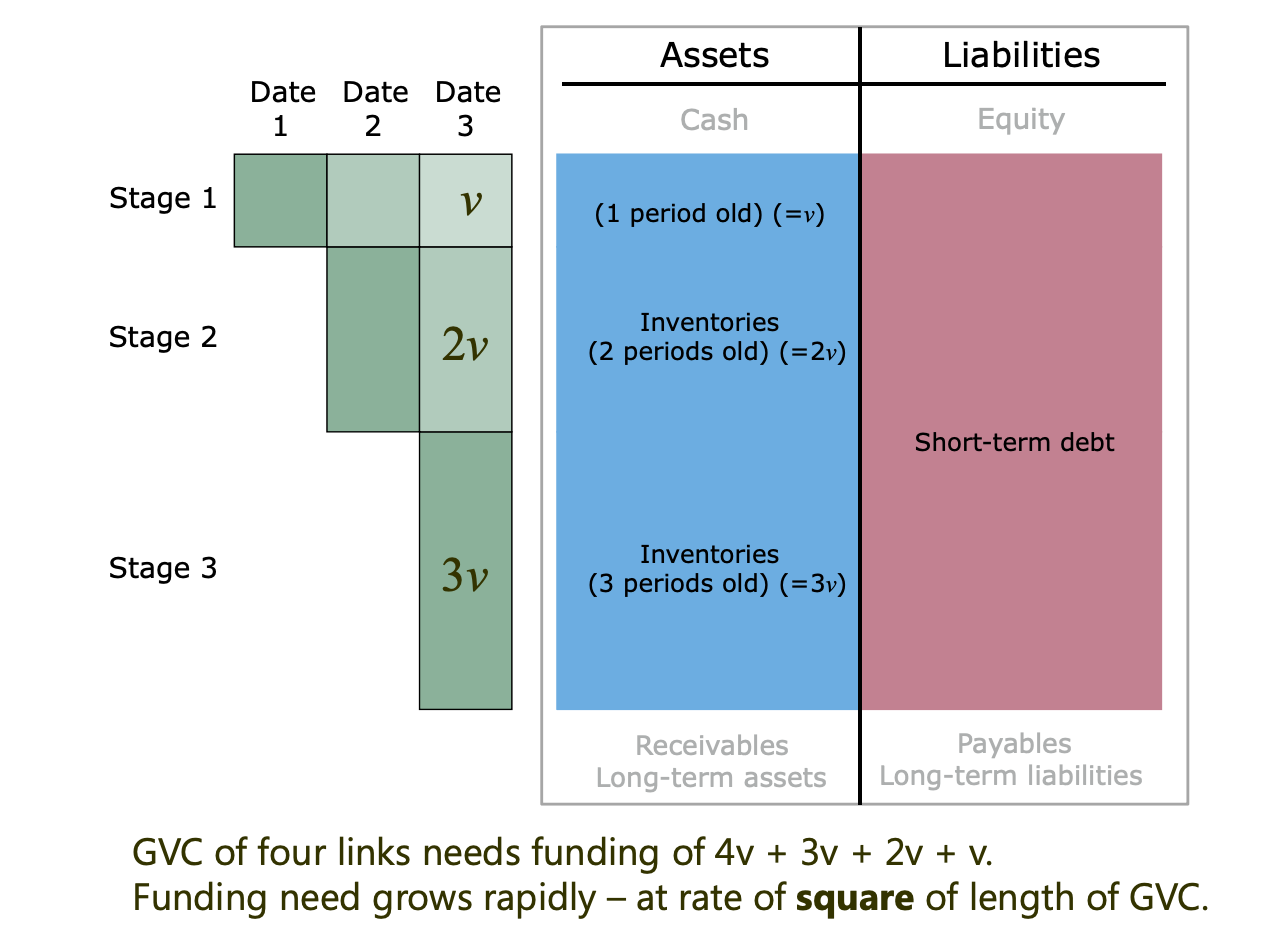

Though Pozsar doesnt acknowledge it, the first person to my knowledge to spell out the connection between the complexity of modern supply-chains (real globalization) and the complexity of global financialization was the brilliant Hyun Song Shin of the BIS back in 2017 in his paper, “Globalisation: real and financial”, which showed how the extension of global value chains was tied to extended networks of finance.

You can see a video of a presentation by Shin here.

Shin showed how extending supply chains increased the demand for credit by the square of the length of the chain.

If you go back in the history of economic thought, the depth of production chains - so called roundaboutness - is a key element in Austrian theories of interest and capital.

Anticipating Pozsar, Shin tied his analysis of trade credit directly to the role of the dollar as the currency intermediating these increasingly “roundabout” transactions. This was also the moment when Shin dropped the immortal line that globalization demands that we:

“to transcend “islands” view of global economy to that of the matrix of balance sheets.”

For me that has been a lode star ever since. I used Shin’s paper to frame the narrative Crashed in this blogpost from back in 2018.

(NB: Before Chartbook there was the blog on adamtooze.com

Note to self: I should spend some time bringing at least some of those earlier blogs into the substack-newsletter era)

In any case, back to 2022.

As Pozsar argues, what we are seeing right now are overlapping disruptions in this twinned system of real and financial flows.

As Pozsar puts it in his most recent Credit Suisse note

Today, supply chains are jammed up and the price of commodities traded in the chains is fluctuating wildly and the underlying order of power that underpins the world economy is in question. When that happens, traders need more credit to make markets and allow goods to flow, a see Chartbook #100. And it begins to matter which currency transactions are conducted in.

Since the outbreak of the war Pozsar has been talking in very dramatic terms about the possible emergence of an alternative, commodity-based currency system. See this early-in-the-crisis Oddlots episode. The most recent Credit Suisse paper gives his Fin-Fin visions a conceptual basis.

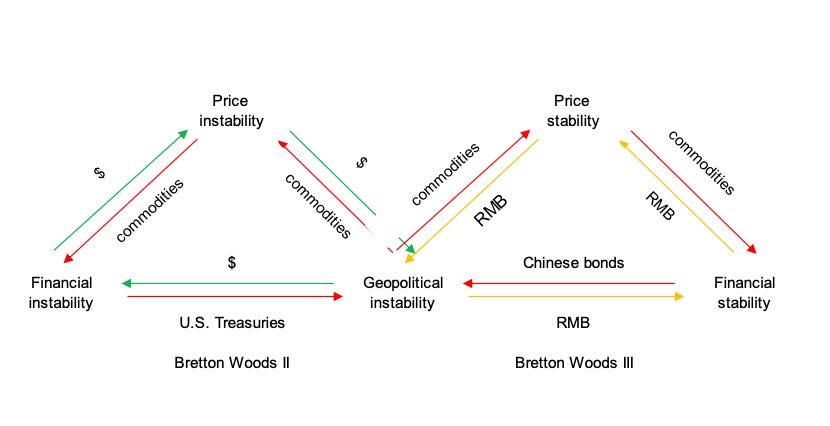

As Pozsar sees it, we are on the cusp of a transition in global currency system.

Under the global economic system we have known since the late 1990s - dubbed Bretton Woods II by a team of economist at Deutsche Bank because China, the main source of growth in trade and real economic growth, unilaterally pegged its currency against the dollar and maintained controls on capital flow, as was the case for Europe and Japan after 1945 - Pozsar argues that “banks create eurodollars and OPEC and China buy U.S. Treasuries with eurodollars.”

This is the triangle that made the dollar the key to the global financial system and the Fed into the indispensable lender and dealer of last resort.

But, what if the sanctions imposed on Russia break that system? What if, instead, Saudi Arabia and Russia start taking payment in Chinese renminbi and we see the emergence of an offshore renminbi market (call it eurorenminbi)? Then, rather than export surplus countries (Saudi, Russia) accumulating dollars, they will accumulate eurorenminbi balances which they will invest in Chinese Treasuries, as China once invested in US Treasuries, or they might choose

“outside money like gold instead of G7 inside money, and commodity reserves instead of FX reserves.

This shift from FX to commodity reserves is the kind of shift from the financial to real economy that hangs over the current moment. It leads Pozsar into an increasingly speculative train of thought:

Commodity reserves will be an essential part of Bretton Woods III, and historically wars are won by those who have more food and energy supplies – food to fuel horses and soldiers back in the day, and food to fuel soldiers and fuel to fuel tanks and planes today. According to estimates by the U.S. DoA (the Department of Agriculture), China holds half of the world’s wheat reserves and 70% of its corn. In contrast, the U.S. controls only 6% and 12% of the global wheat and corn reserves. This has implications for the price level of food and the conversation about Very Large Crude Carriers and the oil trade for the price level of energy.

Those in the know are somewhat skeptical about the likelihood of a truly gigantic disruption to global grain markets. The financial pressures we have seen in the commodity markets have so far not manifested themselves in systemic stress. But, that does not stop Pozsar, who at this point loses himself in what might best be described as a Fin-Fi reverie. I reproduce the structure of the text on the page to capture the incantatory style that Pozsar adopts.

Bretton Woods II served up a deflationary impulse (globalization, open trade, just-in-time supply chains, and only one supply chain [Foxconn], not many), and Bretton Woods III will serve up an inflationary impulse (de-globalization, autarky, just-in-case hoarding of commodities and duplication of supply chains, and more military spending to be able to protect whatever seaborne trade is left).

Empires fall and rise. Currencies fall and rise.

Wars have winners and losers.

When Wellington beat Napoleon, the trade was to buy gilts. I am no expert on geopolitics, but I am an interest rate strategist and I think the level of inflation and interest rates and the size of the Fed’s balance sheet will depend on the steady state that emerges after this conflict is over.

Three is a magic number:

The four prices of money are managed via Basel III and central banks as Dealer of Last Resort.

The four pillars of commodity trading are shaped by war, hopefully not WWIII.

The new world order will bring a new monetary system – Bretton Woods III.

Paul Volcker had it easy... …he “only” had to break the back of inflation but had a unipolar world order and the rise of Eurodollars to support him.

… the markets fussed about was (sic) the impossible trinity (you know, the stuff about monetary policy independence, FX rates, and open capital accounts), but that was about “our currency, your problem”. Jay Powell finding his inner Volcker won’t be enough to break inflation today. He’ll need a strong helping hand…

…a strongman to take on the (inflationary) mess caused by other strongmen?

With texts like this latest remarkable note, Pozsar establishes himself as the most brilliant and intellectually fertile exponent of Fin-Fi today. But, as I argued in previous posts this has to be taken with a pinch of salt. And one has to ask, what present interest these fictions serve.

In Pozsar’s case I was very struck by this passage:

Wheat and oil are connected. Egypt used to be a big importer of Ukranian wheat. If much more oil is about to pass through the Suez Canal, Egypt might consider to introduce its own G-SIB surcharge: raising the fee required to pass through the Suez Canal in order to raise more money for the state’s coffers, such that the Egyptian state can buy more wheat in the wheat market to feed its people.

Hungary lost to Russia in 1956 because the U.S. protected the Suez Canal…

The connection between the Soviet suppression of Hungary’s breakaway national government and the US reaction to the invasion of Egypt by Israel, the British and French in October-November 1956 was not something I had thought of in this context before. It is explored in this interesting article by historian Peter Boyle. This may link to Pozsar’s aside, but to be honest I am not sure, especially the US connection. But clearly he has wide-ranging geopolitical entanglements and resistance to Russian hegemony on his mind.

In any case, the challenge is to stand back from these dramatic vistas for the global economy and global finance and ask ourselves how powerful we think these trends actually are. What is the perspective of realism here?

The conceptual framework is clear. The sanctions imposed within the expanded euro-dollar system (dollar - eurodollar - euro) system clearly do create an incentive to form alternative systems of exchange - based around the ruble and the renminbi, with India and Saudi Arabia as possible partners. But do we really expect these new networks to be anything more than byways? Do we really expect a parallelism to emerge of the type that Pozsar suggests with this diagram?

It, frankly, seems vastly improbable. Policy Tensor (Anusar Farooqui aka @policytensor) and Tim Sahay (aka @70sBachchan) launched a fantastic substack post last week, which gives us a geopolitical grid for Pozsar’s vision.

As they point out the power politics of this moment are complex and Modi’s India is emerging as a pivotal player.

But though I understand the geopolitics, I just don’t see how we get from the map of geopolitical power to the kind of scale of financial transformation that Pozsar’s vision implies.

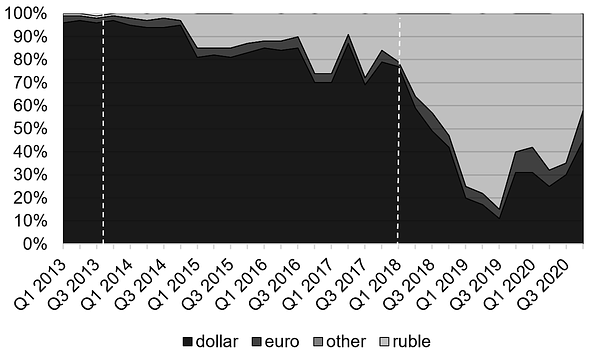

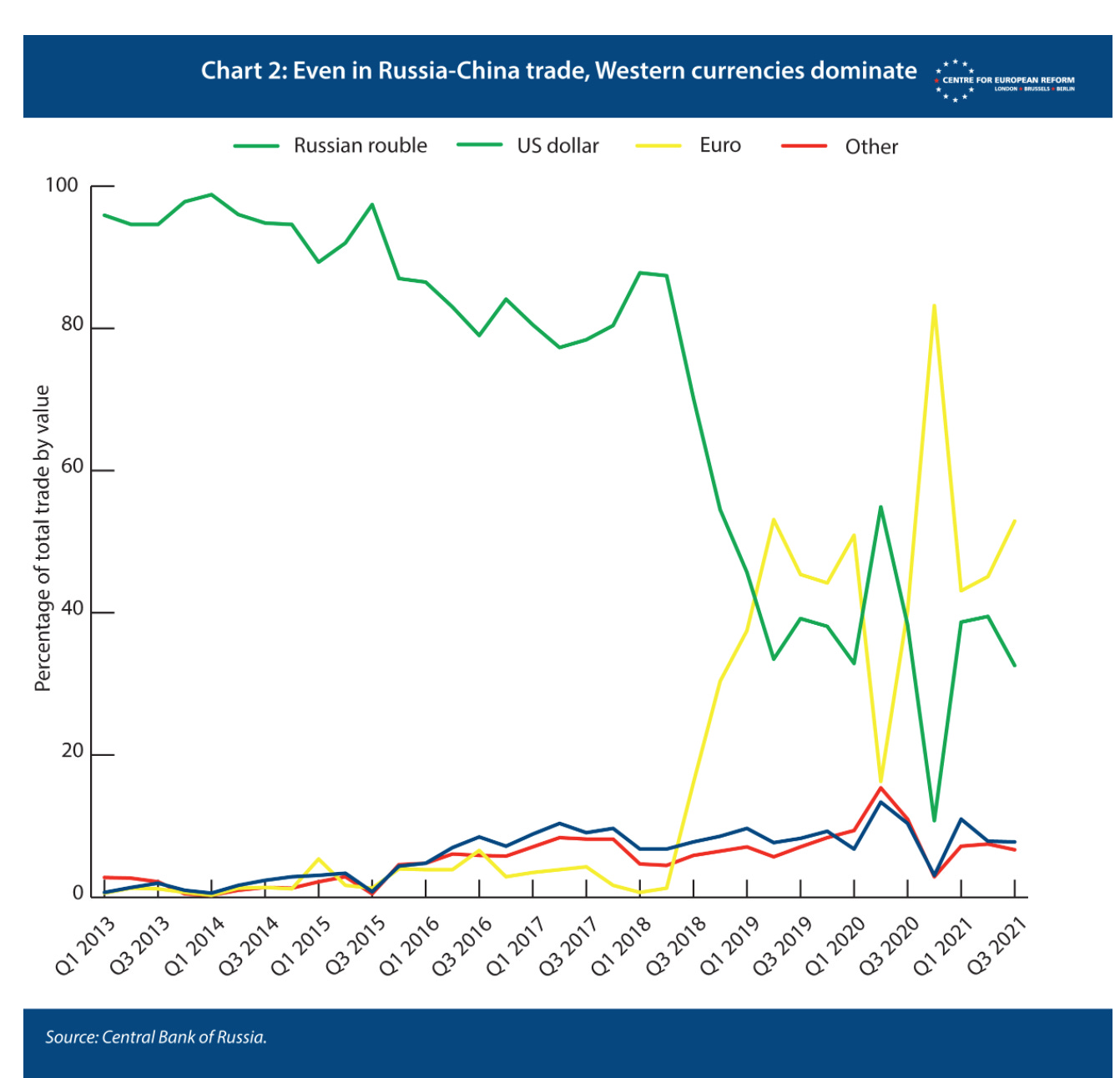

The numbers documenting the total global dominance of the dollar-euro system are familiar. But I found this restatement of the case by Zach Meyers of CER particularly compelling. This graph of the use of dollars and euro in trade between Russia and China since 2014 is particularly striking. Almost all of the trade between the two putative rivals to Western power, currently goes through Western currencies.

Admittedly data does show a dramatic shift in the currency used in India-Russia trade under the impact of sanctions.

But if Russia-China is to form anything like and an equivalent to the global dollar system it has a very long way to go.

My summary for now:

(1) Trade and finance are intimately associated and a disruption in one may be mirrored in a shock to the other. We are living through that reality right now. Whether those shocks are truly systemic in scale remains to be seen. They are not large in relation to the overall financial system. But neither were subprime mortgage backed securities. The difference is that so far we have not seen the kind of ramifying and amplifying effects that turned the mortgage securitization debacle into a North Atlantic financial crisis in 2007-8.

(2) The world is multipolar and so is global trade. Western policy must adjust to that.

(3) There is a huge asymmetry in the world right now between the financial system that remains spectacularly euro-dollar centered and the new multipolarity of power, trade and economic activity.

(4) Given this asymmetry there is a fascination in the cultural and political sphere with the way this glaring asymmetry could be overcome. Not only that, there is a positive desire to see the asymmetry overcome. There is a relish in the discomfiture of the West. The euro-dollar lock feels like the final frontier of Western power, long overdue for overthrow.

(5) Fin-fi is one of the media in which that sense of impending historical change expresses itself.

(6) Given the situation from which it emerges we should read the proliferating genre of Fin-fin symptomatically. It expresses a world historic tension. In some cases it delineates trajectories and seeks to map strategies for policy and investors. In other cases these texts are better read are acts of diplomacy (Larry Fink) motivated by complex constellations of interests.

(7) We should guard against taking Fin-fi literally as a guide to the future rather than as a fascinating expression of the tensions inherent in our current moment.

(8) Identifying and grasping a tension conceptually, is illuminating and engaging for the reasons stated. But the satisfaction thus derived should not be confused with gauging realistically the likelihood of that tension actually being resolved, certainly not in a “logical” direction.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário