Se vcs pensam que o Bolsonaro é maluco, vão gostar desta história (verdadeira) relatada pela Anne Applebaum, a autora de Gulag, Red Famine e Twilight of Democracy.

Nos EUA, terra da liberdade, tudo é possível, até um novo dilúvio, pois não faltarão Noés dispostos a construirem arcas gigantescas para abrigarem americanos e animais.

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

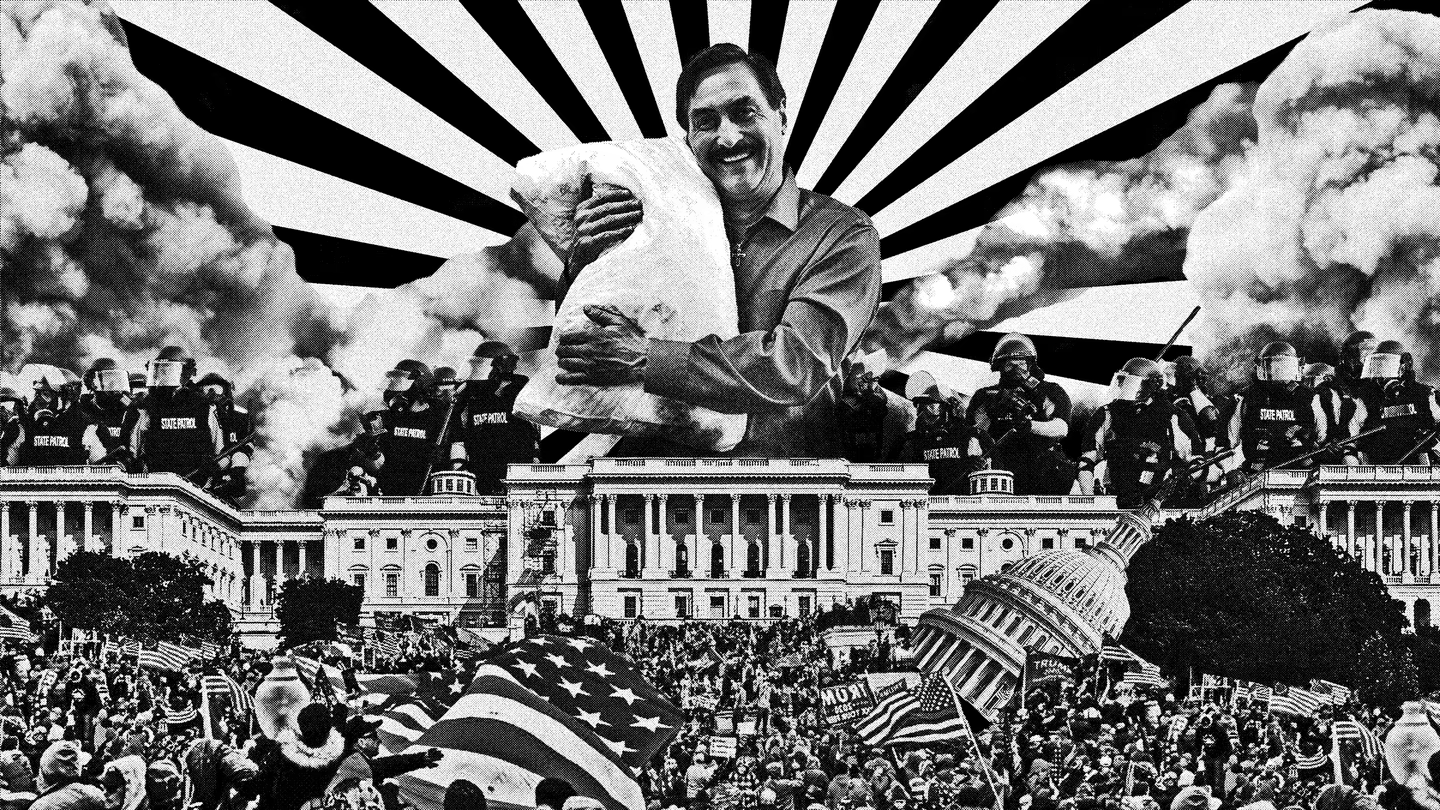

THE MYPILLOW GUY REALLY COULD DESTROY DEMOCRACY

In the time I spent with Mike Lindell, I came to learn that he is affable, devout, philanthropic—and a clear threat to the nation.

About the author: Anne Applebaum is a staff writer at The Atlantic, a fellow at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University, and the author of Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism.

When you contemplate the end of democracy in America, what kind of person do you think will bring it about? Maybe you picture a sinister billionaire in a bespoke suit, slipping brown envelopes to politicians. Maybe your nightmare is a rogue general, hijacking the nuclear football. Maybe you think of a jackbooted thug leading a horde of men in white sheets, all carrying burning crosses.

Here is what you probably don’t imagine: an affable, self-made midwesterner, one of those goofy businessmen who makes his own infomercials. A recovered crack addict, no less, who laughs good-naturedly when jokes are made at his expense. A man who will talk to anyone willing to listen (and to many who aren’t). A philanthropist. A good boss. A patriot—or so he says—who may well be doing more damage to American democracy than anyone since Jefferson Davis.

I met Mike Lindell, the CEO of MyPillow, in the recording studio that occupies the basement of Steve Bannon’s stately Capitol Hill townhouse, a few blocks from the Supreme Court—the same Supreme Court that will, according to Lindell, decide “9–0” in favor of reinstating Donald Trump to the presidency sometime in August, or possibly September. I made it through the entirety of the Trump presidency without once having to meet Bannon but here he was, recording his War Room podcast with Lindell. Bannon has been decomposing in front of our eyes for some years now, and I can report that this process continues to take its course. I walked in during a break and the two men immediately gestured to me to join the conversation, sit at the table with them, listen in on headphones. I demurred. “Anne Applebaum … hmm,” Bannon said. “Should’ve stuck to writing books. Gulag was a great book. How long did it take you to write it?”

In the room adjacent to the basement studio, an extra-large image of a New York Times front page hung on the wall, featuring a picture of Bannon and the headline “The Provocateur.” A bottle of Bio-Active Silver Hydrosol, whatever that is, sat on the desk. The big-screen TV was tuned to MSNBC. This wasn’t surprising: In his podcasts, Bannon carries on a kind of dialogue with Rachel Maddow, playing her sound bites and then offering his own critique. Later, Lindell told me that if it weren’t for attacks by “the left”—by which he means Politico, the Daily Beast, and, presumably, me—his message would never get out, because Fox News ignores him.

Bannon, too, lives outside the Fox bubble these days. Instead, he inhabits an alternate universe in which every minute of every day seems to be entirely devoted to the discussion and analysis of “electoral fraud,” with just a little time devoted to selling wellness products and vitamins that, despite his claims, won’t actually cure COVID-19. Bannon’s podcast, which he says has millions of listeners (it is ranked 59th on Apple Podcasts, so he might be right), is populated by full-time conspiracy theorists, some of whom you have heard of and some of whom you probably haven’t: Peter “Trump Won in a Freakin’ Landslide” Navarro, Rudy Giuliani, Garland Favorito, Willis @treekiller35, Sonny Borrelli, the Pizzagate propagator Jack Posobiec, and, of course, Lindell. Bannon calls them up one by one to report on the current status of the Trump-reinstatement campaign and related fake scandals. There are daily updates. The guests talk fast and loud. It is very exciting. On the day I was at the studio, Bannon was gloating about how President Joe Biden was now “defending his own legitimacy”: “We are going to spring the trap around you, sir!” He kept telling people to “lawyer up.”

Even in this group, Lindell stands out. Not only is he presumably much richer than Garland Favorito and Willis @treekiller35; he is willing to spend his money on the cause. MyPillow has long been an important advertiser on Fox News, so much so that even Trump noticed Lindell (“That guy is on TV more than I am”), but has since widened its net. MyPillow spent tens of thousands of dollars advertising on Newsmax just in the week following the January 6 attack on the Capitol.

And now Lindell is spending on more than just advertising. Last January—on the 9th, he says carefully, placing the date after the 6th—a group of still-unidentified concerned citizens brought him some computer data. These were, allegedly, packet captures, intercepted data proving that the Chinese Communist Party altered electoral results … in all 50 states. This is a conspiracy theory more elaborate than the purported Venezuelan manipulation of voting machines, more improbable than the allegation that millions of supposedly fake ballots were mailed in, more baroque than the belief that thousands of dead people voted. This one has potentially profound geopolitical implications.

That’s why Lindell has spent money—a lot of it, “tens of millions,” he told me—“validating” the packets, and it’s why he is planning to spend a lot more. Starting on August 10, he is holding a three-day symposium in Sioux Falls (because he admires South Dakota’s gun-toting governor, Kristi Noem), where the validators, whoever they may be, will present their results publicly. He has invited all interested computer scientists, university professors, elected federal officials, foreign officials, reporters, and editors to the symposium. He has booked, he says variously, “1,000 hotel rooms” or “all the hotel rooms in the city” to accommodate them. (As of Wednesday, Booking.com was still showing plenty of rooms available in Sioux Falls.)

Wacky though it seems for a businessman to invest so much in a conspiracy theory, there are important historical precedents. Think of Olof Aschberg, the Swedish banker who helped finance the Bolshevik revolution, allegedly melting down the bars of gold that Lenin’s comrades stole in train robberies and reselling them, unmarked, on European exchanges. Or Henry Ford, whose infamous anti-Semitic tract, The International Jew, was widely read in Nazi Germany, including by Hitler himself. Plenty of successful, wealthy people think that their knowledge of production technology or private equity gives them clairvoyant insight into politics. But Aschberg, Ford, and Lindell represent the extreme edge of that phenomenon: Their business success gives them the confidence to promote malevolent conspiracy theories, and the means to reach wide audiences.

In the cases of Aschberg and Ford, this had tragic, real-world consequences. Lindell hasn’t created Ford-level havoc yet, but the potential is there. Along with Bannon, Giuliani, and the rest of the conspiracy posse, he is helping create profound distrust in the American electoral system, in the American political system, in the American public-health system, and ultimately in American democracy. The eventual consequences of their actions may well be a genuinely stolen or disputed election in 2024, and political violence on a scale the U.S. hasn’t seen in decades. You can mock Lindell, dismiss him, or call him a crackhead, but none of this will seem particularly funny when we truly have an illegitimate president in the White House and a total breakdown of law and order.

Lindell had agreed to have lunch with me after the taping. But where to go? I didn’t think it would be much fun to take someone inclined to shout about rigged voting machines and fake COVID-19 cures to a crowded bistro on Capitol Hill. Because Lindell is famously worried about Chinese Communist influence, I thought he would like to pay homage to the victims of Chinese oppression. I booked a Uyghur restaurant.

This proved a mistake. For one thing, the restaurant—the excellent Dolan Uyghur, in D.C.’s Cleveland Park neighborhood—was not at all close to Bannon’s townhouse. Getting there required a long and rather uncomfortable drive, in Lindell’s rented black SUV; he talked at me about packet captures the whole way, one hand on the steering wheel, the other holding up a phone showing Google Maps. Once we got there, he didn’t much like the food. He picked at his chicken kebabs and didn’t touch his spicy fried green beans. More to the point, he didn’t understand why we were there. He had never heard of the Uyghurs. I told him they were Muslims who are being persecuted by Chinese Communists. Oh, he said, “like Christians.” Yes, I said. Like Christians.

He kept talking at me in the restaurant, a kind of stream-of-consciousness account of the packet captures, his mistreatment at the hands of the media and the Better Business Bureau, the dangers of the COVID-19 vaccines, and the wonders of oleandrin, a supplement that he says he and everyone else at MyPillow takes and that he says is 100 percent guaranteed to prevent COVID-19. On all of these points he is utterly impervious to any argument of any kind. I asked him what if, hypothetically, on August 10 it turns out that other experts disagree with his experts and declare that his data don’t mean what he thinks his data mean. This, he told me, was impossible. It couldn’t happen:

“I don’t have to worry about that. Do you understand that? Do you understand I’ve been attacked? I have 2,500 employees, and I’ve been attacked every day. Do I look like a stupid person? That I’m just doing this for my health? I have better things to do—these guys brought me this and I owe it to the United States, to all, whether it’s a Democrat or Republican or whoever it is, to bring this forward to our country. I don’t have to answer that question, because it’s not going to happen. This is nonsubjective evidence.”

The opprobrium and rancor he has brought down upon himself for trying to make his case are, in Lindell’s mind, further proof that it is true. Stalin once said that the emergence of opposition signified the “intensification of the class struggle,” and this is Lindell’s logic too: If lots of people object to what you are doing, then it must be right. The contradictions deepen as the ultimate crisis draws closer, as the old Bolsheviks used to say.

But there is a distinctly American element to his thinking too. The argument from personal experience; the evidence acquired on the journey from crack addict to CEO; the special kind of self-confidence that many self-made men acquire, along with their riches—these are native to our shores. Lindell is quite convinced, for example, that not only did China steal the election, but that “there is a communist agenda in this country” more broadly. I asked him what that meant. Communists, he told me, “take away your right to free speech. You just told me what they are doing to these people”—he meant the Uyghurs. “I’ve experienced it firsthand, more than anyone in this country.”

The government had taken his freedom away? Put him in a reeducation camp? “I don’t see anybody arresting you,” I said. He became annoyed.

“Okay, I’m not talking about the government,” he said. “I’m talking about social media. Why did they attack me? Why did bots and trolls attack all of my vendors? I was the No. 1 selling product of every outlet in the United States—every one, every single one, all of them drop like flies. You know why? Because bots and troll groups were hired. They were hired to attack. Well, now I’ve done investigations. They come out of a building in China.”

It is true that there has been some organized backlash against MyPillow, which is indeed no longer stocked by Bed Bath & Beyond, Kohl’s, and other retailers. But I suspect that this reaction is every bit as red-white-and-blue as Lindell himself: Plenty of Americans oppose Lindell’s open promotion of both election and vaccine conspiracy theories, and are perfectly capable of boycotting his company without the aid of Chinese bots. Lindell’s lived experience, however, tells him otherwise, just like his lived experience tells him that COVID-19 vaccines will kill you and oleandrin won’t. Lived experience always outweighs expertise: Nobody can argue with what you feel to be true, and Lindell feels that the Chinese stole the election, sent bots to smear his company, and are seeking to impose communism on America.

Although he describes the packet captures as “cyberforensics”—indisputable, absolute, irreversible proof of Chinese evildoing—Lindell is more careful about evidence that isn’t “nonsubjective.” When I asked him how exactly Joe Biden’s presidency was serving the interests of the Chinese Communist Party, for example, his reasoning became more circuitous. He didn’t want to say that Joe Biden is himself a Communist. Instead, when I asked for evidence of communist influence on Biden, he said this: “Inauguration Day—I’ll tell you—Inauguration Day, he laid off 50,000 union workers. Boom! Pipeline gone. The old Democrat Party wouldn’t lay off union workers.”

In other words, the evidence of Joe Biden’s links to the Chinese Communist Party was … his decision to close the Keystone XL pipeline. Similarly convoluted reasoning has led him to doubt the patriotism of Arizona Governor Doug Ducey as well as Georgia Governor Brian Kemp and Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, all of whom deny the existence of serious electoral cheating in their states. “My personal opinion,” he told me, is that “Brian Kemp is somehow compromised and maybe could be blackmailed or in on it or whatever. I believe Raffensperger’s totally in on it.”

In on what? I asked.

“In on whatever’s going on …”

I asked if he meant the Chinese takeover of America. Was Raffensperger pro-China?

“I believe he’s pro-China.”

Alongside the American business boosterism, Lindell’s thinking contains a large dose of Christian millenarianism too. This is a man who had a vision in a dream of himself and Donald Trump standing together—and that dream became reality. No wonder he believes that a lot of things are going to happen after August 10. It’s not just that the Supreme Court will vote 9–0 to reinstate Trump. It is also that America will be a better place. “We’re going to get elected officials that make decisions for the people, not just for their party,” Lindell said. There will be “no more machines” in this messianic America, meaning no more voting machines: “On both sides, people are opening their eyes.” In this great moment of national renewal, there will be no more corruption, just good government, goodwill, goodness all around.

That moment will be good for Lindell, too, because he will finally be able to relax, knowing that “I’ve done all I can.” After that, “everything will take its course. And I don’t have to be out there every day fighting for media attention.” He won’t, in other words, have to be having lunch with people like me.

Alas, a happy ending is unlikely. He will not, on August 10, find that “the experts” agree with him. Some have already provided careful explanations as to why the “packet captures” can’t be what he says they are. Others think that the whole discussion is pointless. When I called Chris Krebs, the Trump administration’s director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, he refused even to get into the question of whether Lindell has authentic data, because the whole proposal is absurd. The heavy use of paper ballots, plus all of the postelection audits and recounts, mean that any issues with mechanized voting systems would have been quickly revealed. “It’s all part of the grift,” Krebs told me. “They’re exploiting the aggrieved audience’s confirmation bias and using scary yet unintelligible imagery to keep the Big Lie alive, despite the absence of any legitimate evidence."

What will happen when Lindell’s ideological, all-American, predicted-in-a-dream absolute certainty runs into a wall of skepticism, disbelief, or—even worse—indifference? If history is anything to go by … nothing. Nothing will happen. He will not admit he is wrong; he will not stop believing. He will not understand that he was conned out of the millions he has spent “validating” fake data. (One has to admire the salesmanship of the tech grifters who talked him into all of this, assuming they exist.) He will not understand that his company is having trouble with retailers because so many people are repulsed by his ideas. He will not understand that people attack him because they think what he says is dangerous and could lead to violence. He will instead rail against the perfidy of the media, the left, the Communists, and China.

Certainly he will not stop believing that Trump won the 2020 election. The apocalypse has been variously predicted for the year 500, based on the dimensions of Noah’s Ark; the year 1033, on the 1,000th anniversary of Jesus’s birth; and the year 1600, by Martin Luther no less; as well as variously by Jehovah’s Witnesses, Nostradamus, and Aum Shinrikyo, among many others. When nothing happened—the world did not end; the messiah did not arrive—did any of them throw in the towel and stop believing? Of course not.

Lindell mostly speaks in long, rambling monologues filled with allusions and grievances; he circles back again and again to electoral fraud, to the campaigns against him, to particular interviewers and articles that he disputes, some of it only barely comprehensible unless you’ve been following his frequent media appearances—which I have not. At only one moment was there a hint that this performance was more artful than it appeared to be. I asked him about the events of January 6. He immediately grew more precise. “I was not there, by the grace of God,” he said. He was doing media events elsewhere, he said. Nor did he want to talk about what happened that day: “I think that there were a lot of things that I’m not going to comment on, because I don’t want that to be your story.”

Not too long after that, I suddenly found I couldn’t take any more of this calculated ranting. (I can hear that moment on the recording, when I suddenly said “Okay, enough” and switched off the device.) Although he ate almost nothing, Lindell insisted on grabbing the check, like any well-mannered Minnesotan would. In the interests of investigative research, I later bought a MyPillow (conclusion: it’s a lot like other pillows), so perhaps that makes us even.

When we walked outside, I thought that I might say something dramatic, something cutting, something like “You realize that you are destroying our country.” But I didn’t. He is our country after all, or one face of our country: hyper-optimistic and overconfident, ignorant of history and fond of myths, firm in the belief that we alone are the exceptional nation and we alone have access to exceptional truths. Safe in his absolute certainty, he got into his black SUV and drove away.

*Photo-illustration images: MyPillow; AP; Brent Stirton / Michael Negro / Pacific Press / LightRocket / Getty