The plunge in world oil prices—from $105 to about $50 per barrel since mid-2014—has been a boon for oil-importing countries, while presenting challenges for oil exporters.

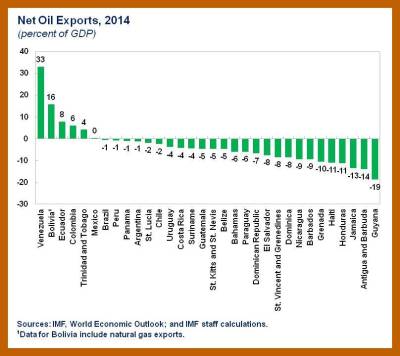

In general, oil importers will enjoy faster growth, lower inflation, and stronger external positions, and most will not encounter any significant fiscal pressures. Oil exporters will tend to face slower growth and weaker external current account balances and some will run into fiscal pressures, since many rely on direct oil-related revenues. One country that stands out is Venezuela, which had been experiencing severe economic imbalances before oil prices began to fall and now finds itself in an even more precarious position.

A new reality

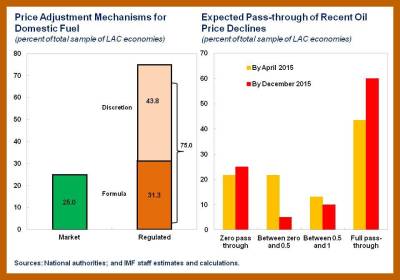

Many countries are adapting well to this new global environment by allowing lower world oil prices to pass through into lower domestic energy costs. This increases the disposable income of consumers and businesses through cheaper costs for transportation and electricity. This policy supports growth and eases inflationary pressures. It also helps stabilize the external current account balance by stimulating demand for non-oil imports, which can partly offset the decline in oil imports. In Latin America and the Caribbean, our estimates suggest that 60 percent of these countries—such as Barbados, Costa Rica and Guatemala—will allow for a full pass through from world to domestic fuel prices by end 2015, while less than 30 percent will not allow any pass through.

Cuts both ways: impact on fiscal balances

For net oil importers, world oil prices can affect fiscal balances in several ways that may offset each other. The value of taxes on oil imports (both value-added taxes as well as ad valorem import duties) will probably decline, but the costs of fuel subsidies may decline as well, especially if the government does not allow full pass through of the decline in world oil prices. Our analysis suggests that the fiscal position in most net oil importing countries would strengthen moderately by the decline in world oil prices. The fiscal position in some of these countries is improving because the governments are not allowing the full pass through of lower world oil prices into domestic fuel prices.

But the effect of world oil prices on the fiscal position in net oil exporters (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela) is negative. In most of these countries, a state-owned oil company dominates this sector, which provides fiscal revenues through income taxes, dividends, and royalties paid to the government. These companies may hold monopolies on domestic sales of petroleum products and may bear the costs of domestic fuel subsidies.

Ecuador, Mexico, and Trinidad and Tobago have already begun to curb spending to offset the decline in hydrocarbons-related revenues. The Mexican government is raising the domestic price of gasoline by 1.9 percent in 2015, which will enhance the revenues from domestic sales, and it purchased insurance from the market that helped limit the decline in oil-related revenues in 2015. The government will need to undertake additional fiscal adjustment in 2016, since this insurance provided a hedge for just 2015.

Colombia relies on a fiscal rule that spreads out the adjustment to shifts in world oil prices. This means the fiscal deficit will widen in 2015, with the fall in oil-related revenues. However, in the coming years the government will need to raise non-oil revenues to reach the legal targets for the structural fiscal balance while protecting key expenditure programs.

Colombia relies on a fiscal rule that spreads out the adjustment to shifts in world oil prices. This means the fiscal deficit will widen in 2015, with the fall in oil-related revenues. However, in the coming years the government will need to raise non-oil revenues to reach the legal targets for the structural fiscal balance while protecting key expenditure programs.

Bolivia will experience a significant loss in revenues, since the price of its natural gas exports are linked to spot world oil prices, but the government has built up considerable buffers of deposits and net international reserves to give itself room for maneuver in the near team.

The fiscal position of Venezuela will suffer the most from the decline in world oil prices, as its public sector derives a large share of its fiscal revenues from oil exports. In addition, the domestic price of gasoline is expected to remain close to zero, which virtually eliminates any potential revenues from domestic sales.

Fiscal difficulties in Venezuela could create pressures on countries that import oil from Venezuela through the Petrocaribe arrangement—a Venezuelan energy-assistance program for some Central American and Caribbean countries. In many of these countries, the decline in the value of oil imports exceeds the projected financing from Petrocaribe. However, many countries use the subsidy component of Petrocaribe financing to support long-term spending, and could face a difficult fiscal adjustment if this source of financing were to be cut.

Policy implications

The new outlook for world oil prices will benefit some countries, while presenting challenges for others. In general, this new outlook does not pose a threat to macroeconomic stability in the region, because most countries will continue to maintain sound policy frameworks. The notable exception is Venezuela, where the significant loss in oil export revenues will aggravate a situation that was already tenuous.

For those countries that have not done so already, the drop in oil prices provides a good opportunity to eliminate poorly targeted subsidies and to establish pricing mechanisms that allow for an automatic adjustment of domestic prices to changes in international fuel prices. The new global environment also underscores the importance of diversifying the sources of fiscal revenue to avoid an overreliance on fiscal income from either oil exports or imports.

This article is published in collaboration with IMFDirect. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Robert Rennhack is Deputy Director in the Western Hemisphere Department of the International Monetary Fund. Fabián Valencia is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department covering Mexico.

Image: A general view of the Petrobras refinery plant in Cubatao February 25, 2015. REUTERS/Paulo Whitaker