A eliminação da pobreza na China

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

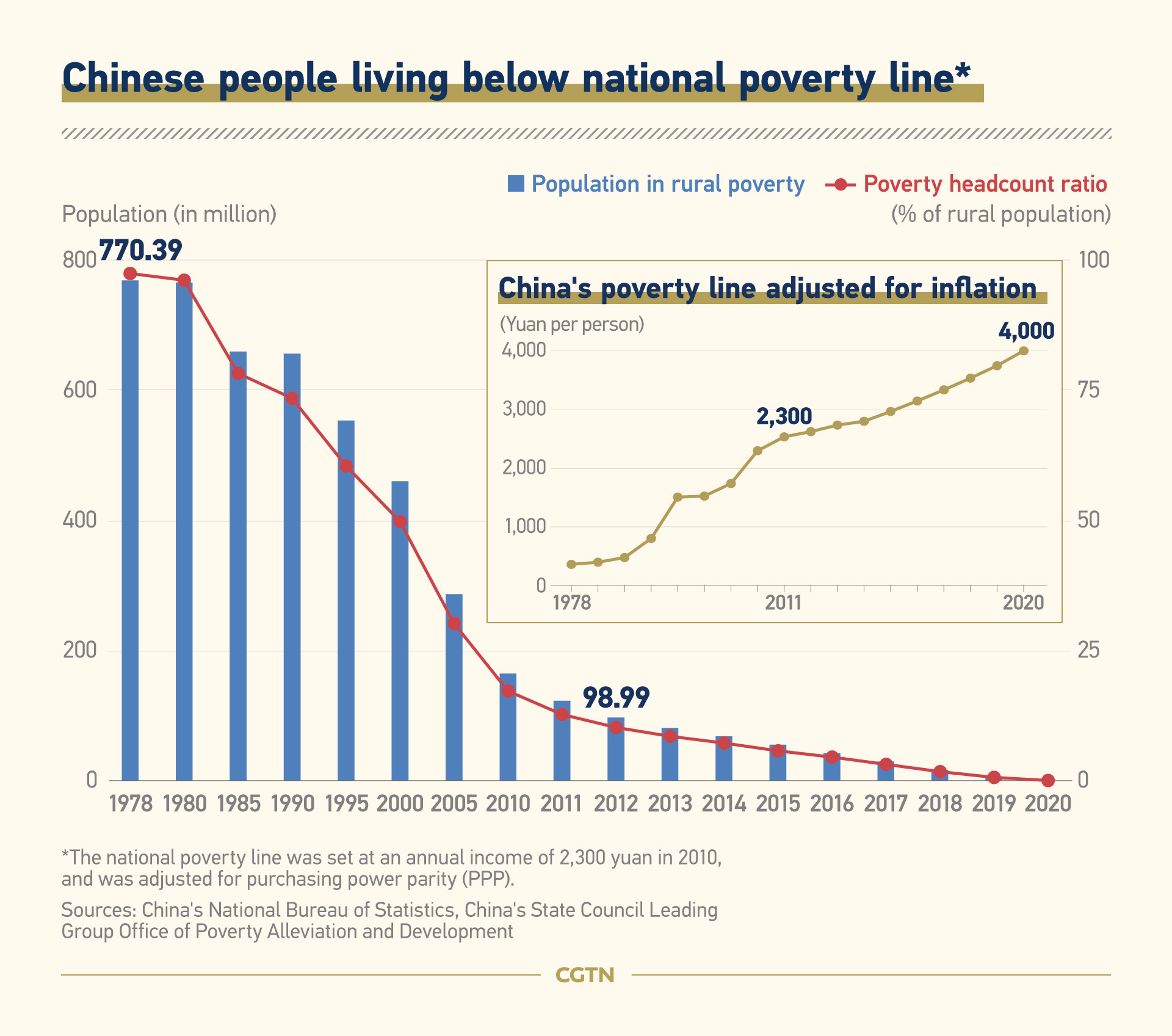

O extraordinário feito da sociedade chinesa deve ser saudado no seu mérito próprio e nos seus resultados práticos: PELA PRIMEIRA VEZ NA HISTÓRIA DA HUMANIDADE, uma realização dessas dimensões ocorre num espaço de tempo inferior a duas gerações, num país de mais um bilhão de habitantes, com mais ou menos 800 milhões de pobres 40 anos atrás. Esse feito vai figurar para sempre nos livros de história econômica e deve ser reconhecido como uma realização de todo o povo chinês, circunstancialmente guiado por um Estado autocrático e pela ditadura de um partido único.

October 17 marks China's National Poverty Relief Day, a reminder that the country has reached the final stage of its mission to eradicate extreme poverty by the end of 2020.

With only 75 days left for the year, how far is China from achieving that goal and what's next?

Most provinces and regions have already been declared free of absolute poverty.

By the end of 2019, the number of poor rural residents in the country plunged from 98.99 million in 2012 to 5.51 million in 2019, showed data from China's National Bureau of Statistics.

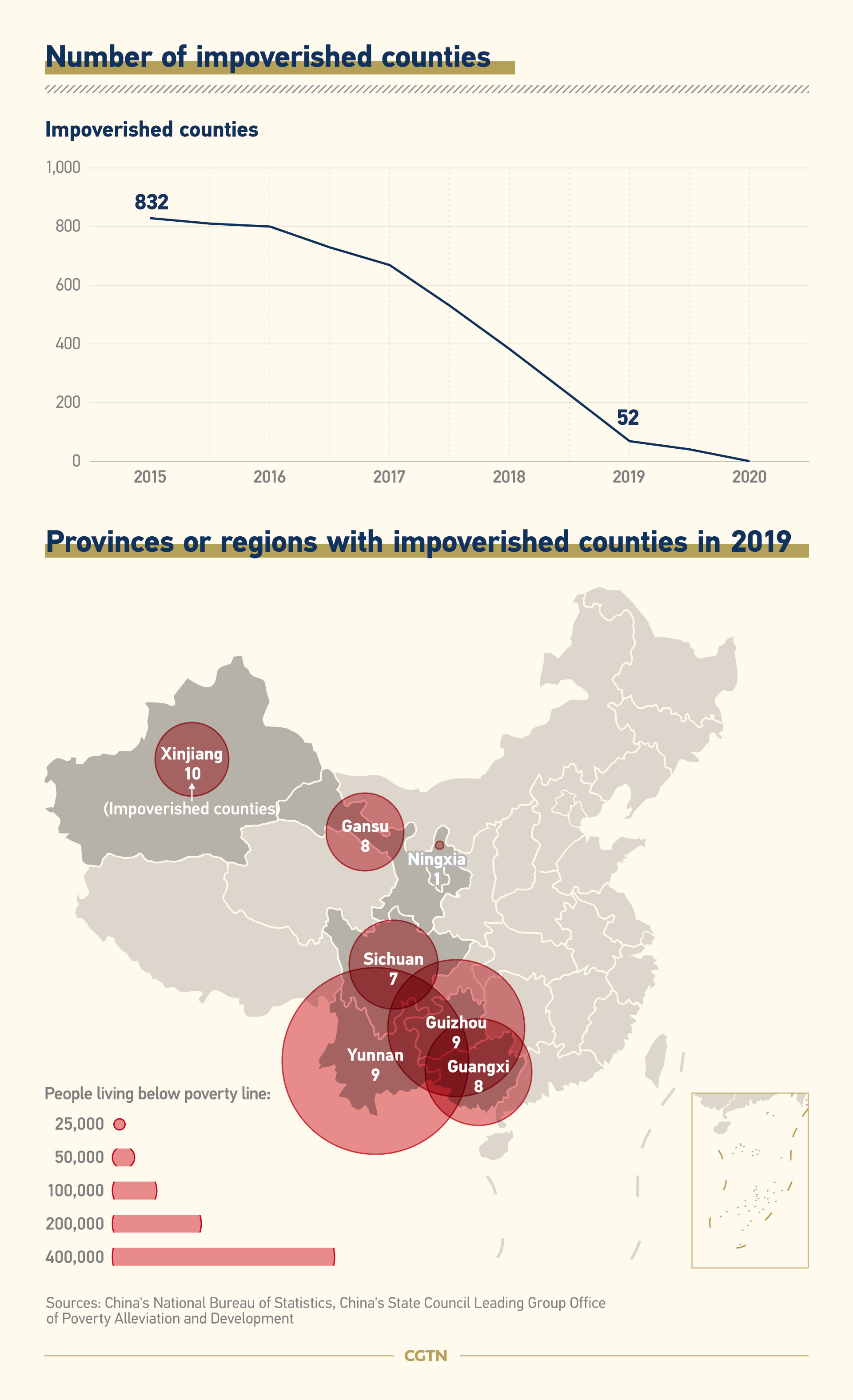

And the number of impecunious counties in China has fallen from 832 in 2015 to 52 in 2019, according to the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development.

In 2020, 52 poverty-stricken counties in seven provinces and regions became key poverty-eradication battlegrounds. Some of them have met the standards for gaining the poverty-free status, while others are set to accomplish the goal in the next two to three months.

2020 is the final year of China's new round of anti-poverty drive, which started in 2012 with the aim to end domestic poverty before 2021, the centenary of the founding of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

The sweeping campaign to defeat rural poverty was part of building a moderately and comprehensively prosperous society.

But 2020 has been no ordinary year for China and the world. COVID-19 epidemic coupled with floods in southern China posed daunting challenges to the national fight against penury.

Chinese President Xi Jinping stressed at a symposium on securing a decisive victory in poverty alleviation in March that lifting all rural residents living below the current poverty line out of poverty by 2020 is a solemn promise made by the CPC Central Committee, and it must be fulfilled on time.

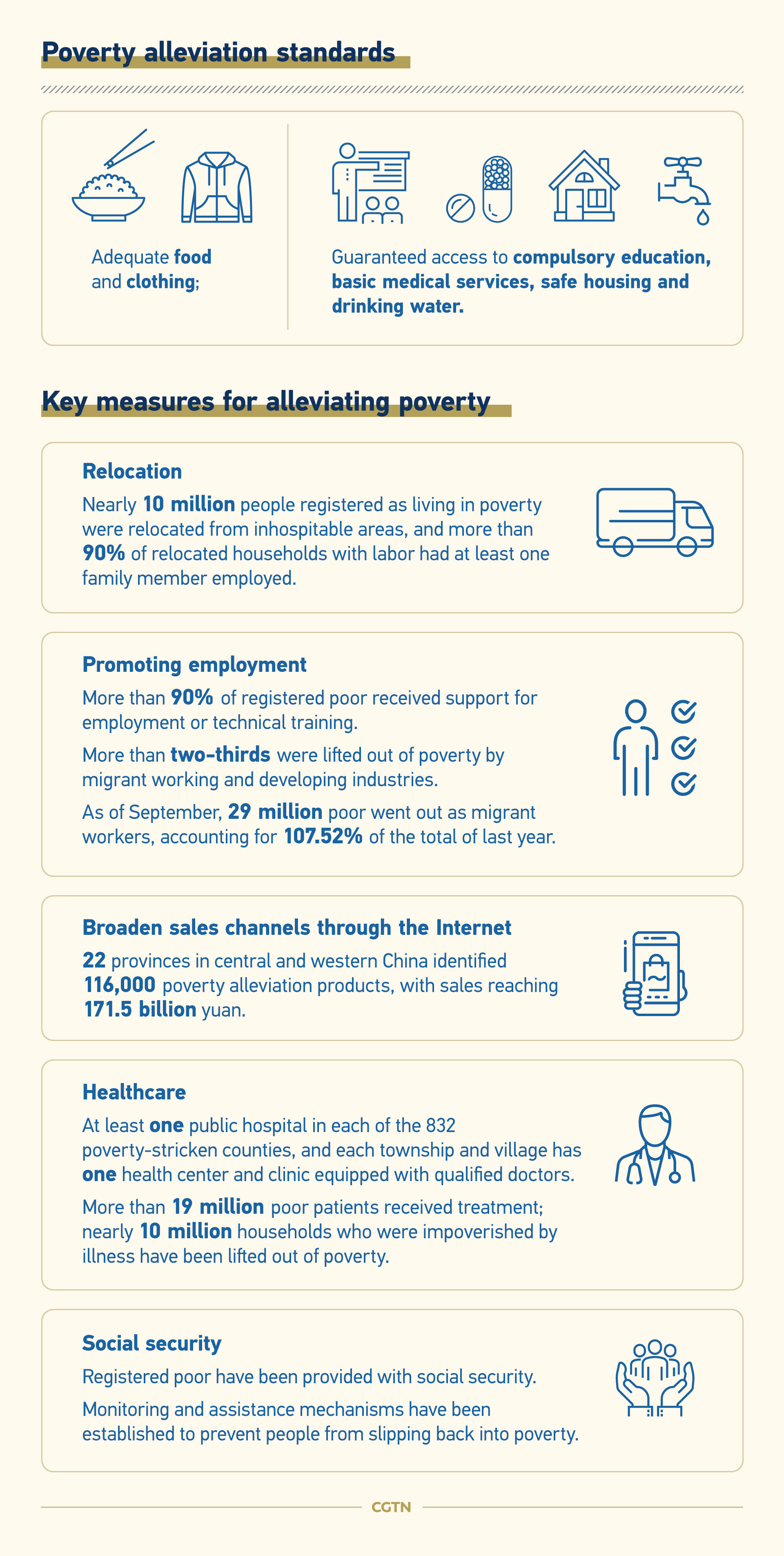

The present poverty eradication goals consist of not only eliminating all instances of absolute poverty on schedule, but also consolidating the achievements of poverty reduction efforts, ensuring that people who have gotten out of poverty do not fall back into it.

"Being lifted out of poverty is not an end in itself but the starting point of a new life and a new pursuit," Xi said at the poverty alleviation symposium, emphasizing the need to synchronize poverty alleviation with rural revitalization.

After China achieves building a moderately prosperous society in all respects, it must make all-out efforts to advance rural revitalization to further address issues such as the urban-rural imbalance, Xi said during an inspection tour to Sanjia Village in Tengchong CIty, southwest China's Yunnan Province in January.

Liu Yongfu, director of the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development, highlighted that poverty alleviation should be a continuous and sustainable work, as "relative poverty" will still exist even after the country eliminates "absolute poverty" by 2020.

Graphics by Chen Yuyang

Read more about how China is leading global anti-poverty efforts

How China is championing climate change mitigation and poverty reduction

Read more:

Data reveals how far China's from a moderately prosperous society in all respects

Read more:

Latest data reveal how far away China is from the 2020 poverty elimination goal

Graphics: Ending China's poverty by 2020