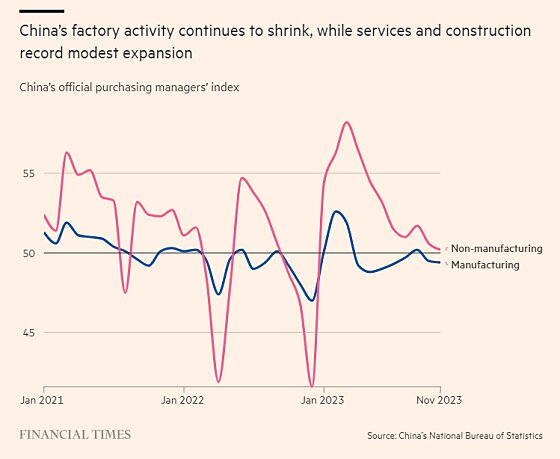

Meanwhile, non‐manufacturing industries just hit “the lowest reading since China was swept by Covid last December.”

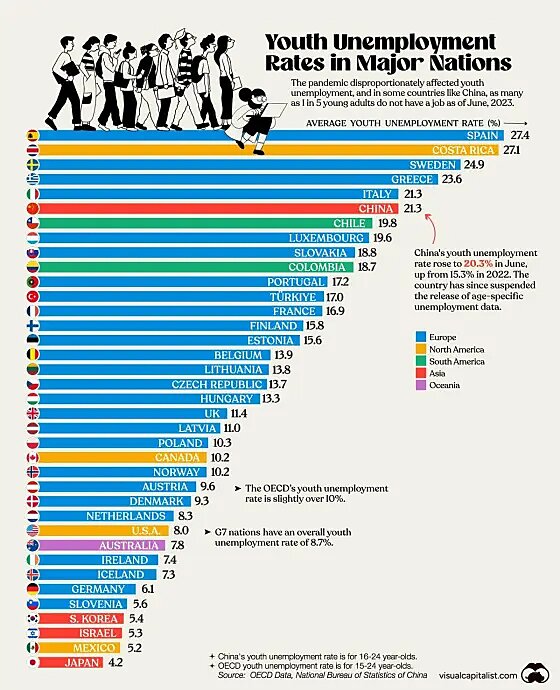

Outside the corporate sector, other problem signs have emerged. Most notably, the youth unemployment rate hit a record high of 21.3 percent in June … right before the government ceased to publish the official number. (Always a good sign!) Add students to the total, and the rate could be 46.5 percent. Shockingly, nixing the stat didn’t make the problem go away: As the WSJ’s Josh Zumbrun writes, social media reports and independent data show that youth unemployment remains a “troubling story” in China, even if we can’t pin down exactly how troubling it is. Meanwhile, one private forecaster’s “measure of job openings began to plunge in May, and as of early December was 35 percent lower than a year earlier—not a great sign in an economy desperately trying to absorb huge numbers of jobless youth.” Assuming the rate is still hovering around those June levels, it’d be one of the highest in the world:

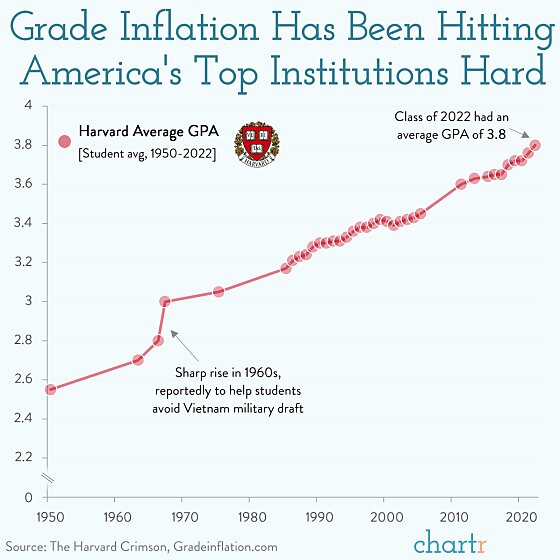

One of the issues here, the New York Times notes (along with many others), is a policy‐driven mismatch between the types of young workers China’s planners once wanted its education system to produce (college grads to work in services or government) and the “strategic” industries the government is currently supporting (which need factory workers trained primarily at vocational schools). Thus, for example, “The number of teenagers entering vocational and technical high schools plummeted 25 percent between 2010 and 2021,” while “about 60 percent of the Chinese population turning 18 enroll at a university”—up from 10 percent in 2000. Now, China’s burgeoning EV industry faces “a shortfall of skilled technicians as young people shun manufacturing careers.”

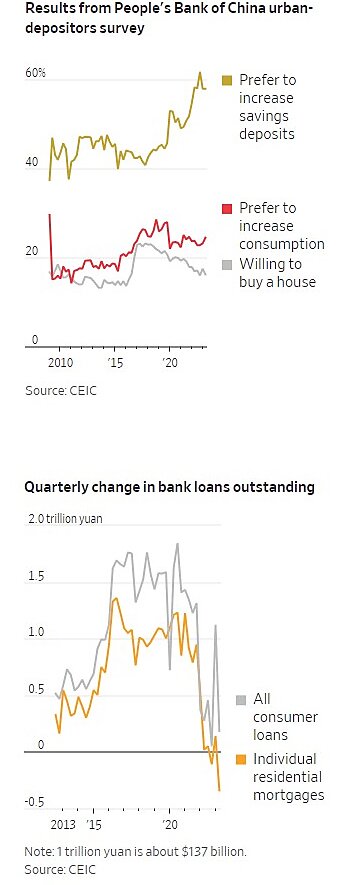

Problems are not, however, isolated among China’s young. As the Peterson Institute’s Adam Posen documented in August, Chinese households seem to have lost confidence in the future of the Chinese economy and government. As a result, they are saving more—a lot more—and consuming less: Compared with 2015, bank deposits (as a share of GDP) are up by 50 percent and remain elevated, while consumption of durable goods has declined by about one‐third. Private investment (down two‐thirds since 2015) shows a similar insecurity.

WSJ’s Nathanial Taplin came to a similar conclusion a couple weeks later after looking at a different set of consumer survey and loan data: “Beijing has failed to convince households that their financial future is secure in the post‐Covid era.”

Unless the CCP focuses more on consumption and less on “grandiose industrial policy and geopolitics,” Taplin adds, a “painful period of economic stagnation” might be ahead. He and Posen are certainly not alone in their diagnoses and warnings.

Other signs of household stress have since emerged. Earlier this month, we learned that “defaults by Chinese borrowers have surged to a record high … highlighting the depth of the country’s economic downturn and the obstacles to a full recovery.” Making matters worse is Chinese law, which requires these 8.5 million people to be “officially blacklisted” and thus “blocked from a range of economic activities, including purchasing aeroplane tickets and making payments through mobile apps such as Alipay and WeChat Pay, representing a further drag on an economy plagued by a property sector slowdown and lagging consumer confidence.” Lower incomes and higher costs, meanwhile, have caused China’s massive state health insurance system to lose tens of millions of subscribers in 2022—an “unprecedented” decline that, after years of growth, is expected to continue this year.

Structural Headwinds and ‘Japanification’?

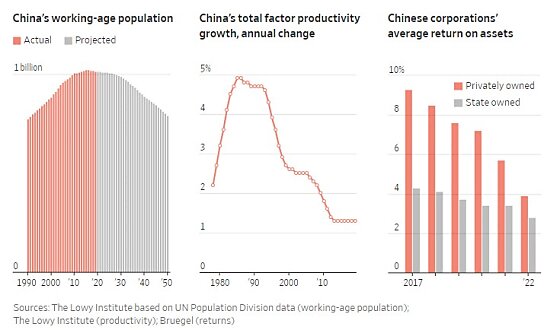

Other, longer‐term headwinds also remain problematic, as I first documented here back in 2021 and as my Cato colleague Clark Packard recently updated in an essay for our ongoing globalization project. Along with debt, China’s demographics (low birth rates, a rapidly aging population, shrinking workforce, etc.), difficulty attracting and retaining both homegrown and global talent, and stagnating economic dynamism and productivity pose further challenges to future economic growth, government budgets, and political stability.

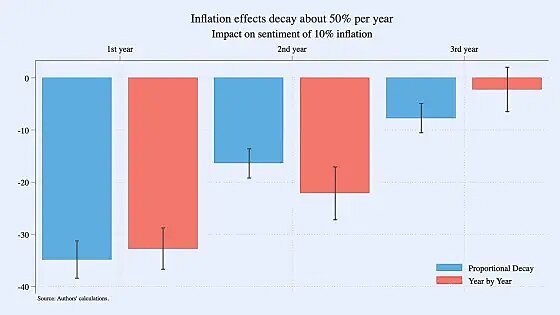

Combine these headwinds with the shorter‐term issues, and the narrative around China has shifted radically in the last year. Analysts once attracted to (or worried about) strong growth are suddenly reversing course and worrying about excess capacity and stagnation. Unlike most other big economies, in fact, China is now grappling with deflation: Consumer prices went negative in July, returned there in October, and declined even more last month, indicating that a brief late‐summer revival may have been a “dead‐cat bounce.” Producer prices, meanwhile, have been negative for a full year.

Perhaps most troubling for the Chinese economy is the fact that these problems have arisen despite “a slew of supportive measures from Beijing to boost sentiment and growth since mid‐2023.”

Pushing on a string, indeed.

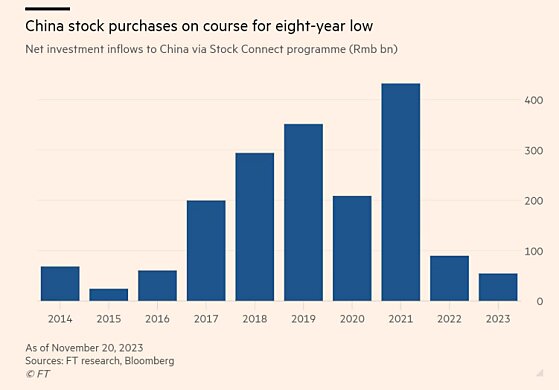

None of this means that China is on the verge of an all‐out economic collapse or anything, but investors have significantly revised their bets on the Chinese economy. As of late November, “more than three‐quarters of the foreign money that flowed into China’s stock market in the first seven months of the year has left, with global investors dumping more than $25bn worth of shares despite Beijing’s efforts to restore confidence.”

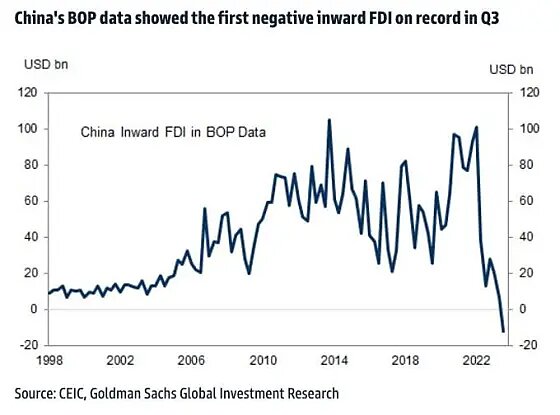

And foreign direct investment is fleeing China in ways not seen in decades—not just slowing their investments there but “now ditching Chinese investments and pulling money out at a remarkably rapid pace” for the first time ever.

If these FDI trends continue for the rest of the year, the FT’s Robin Wigglesworth adds, “China is on track to attract less FDI than Poland did in 2022, and less than half of what Sweden did”—and, he notes, even that might be too optimistic.

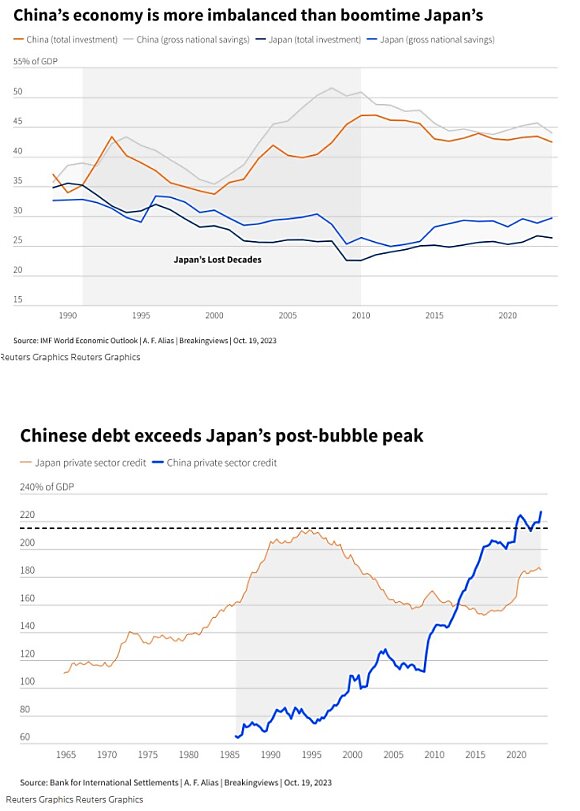

As a result, many analysts who once confidently predicted China’s economy would soon overtake the United States’ have lowered their growth projections, extended their timelines, or even ditched them altogether. Now, commentators openly wonder if China will be the “next Japan,” meaning a rapidly growing economy once predicted to supplant the United States, but instead—thanks to high levels of debt and state‐directed economic distortions combined with slower growth and demographic and external pressures—ends up facing not just a few months or even a year of economic malaise but decades:

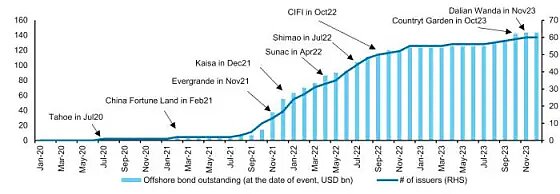

Some economists see alarming parallels between China’s current predicament and the experience of Japan, which struggled for years with deflation and stagnant growth. In the 1990s, a collapse in stock markets and real‐estate values in Japan pushed companies and households to drastically cut back spending to service burdensome debts—a so‐called balance‐sheet recession that some see taking shape in China today.

As one analyst recently put it this summer: “When the real estate bubble started collapsing last year, all these Chinese economists began to worry about a Japan‐like situation where so many people are paying down debt all at the same time and [the] economy could then fall into a deflationary spiral. I think that is actually already happening in China.” The latest deflation data would appear to confirm his fears (at least for now).

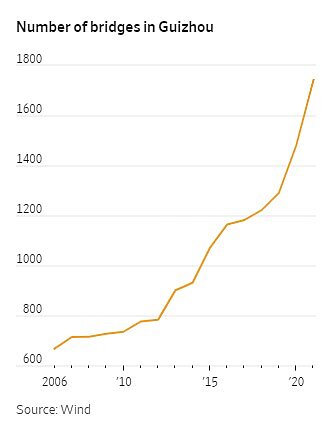

Beyond the aforementioned debt and deflation similarities between the two nations, there are plenty of others: banking, property, demographics, a high‐savings/investment economic growth model, and policy‐driven malinvestment and overcapacity (especially in manufacturing and infrastructure). It’s not a stretch to think that China’s economic engine will be sputtering for years to come, much like Japan’s did decades ago.

In fact, China’s situation is in many ways worse than Japan’s was when it began to stall. For starters, China is still relatively poor:

China’s national income per person reached about $12,850 last year, below the current threshold of $13,845 that the World Bank classifies as the minimum for a “high‐income” country. Japan’s per capita national income in 2022 was about $42,440, and the U.S.’s was about $76,400.

China’s economic imbalances are also bigger than Japan’s were in 1990, as are its total debts (that we know of!):

As Goldman‐Sachs notes, China’s demographics headwinds also are bigger than Japan’s were in the 1990s, and its housing sector weakness is “more pronounced” too. Japan also didn’t pursue its own version of China’s wasteful and ineffective Belt & Road Initiative. And instead of backing off the economic meddling like Japan eventually did, China’s now leaning in:

Guided by a desire to strengthen political control, Xi’s leadership has doubled down on state intervention to make China an even bigger industrial power, strong in government‐favored industries such as semiconductors, EVs and AI.

While foreign experts don’t doubt China can make headway in these areas, they alone aren’t enough to lift up the entire economy or create enough jobs for the millions of college graduates entering the workforce, economists say.

Just yesterday, in fact, China’s top central planners “vowed to make industrial policy their top economic priority next year,” thus letting down investors who were hoping the government would shift away from “technology self‐reliance” toward more pro‐growth policy instead.

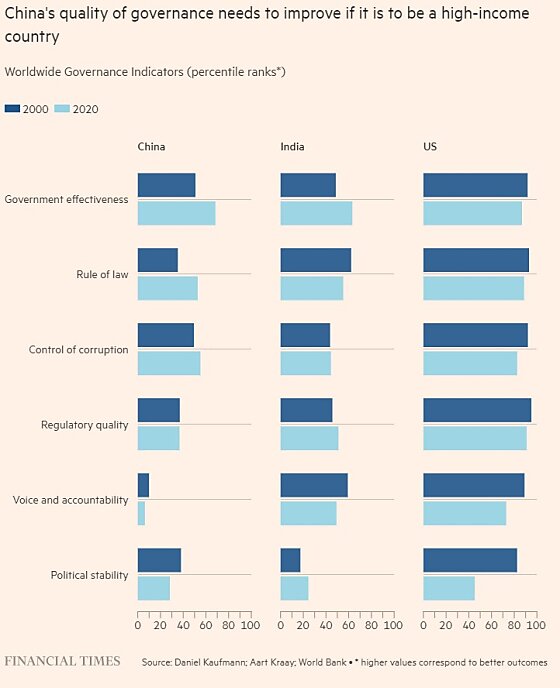

Finally, there are the negatives raised by China’s political system, aside from the much‐publicized corruption and institutional shortcomings (see chart below). As discussed last year, for example, authoritarian regimes have informational problems from both the bottom up (e.g., local governments distorting facts/data to avoid punishment) and the top down (e.g., the central government doing the same to make its regime look good). Autocratic systems also provide government officials with the mechanisms to forcibly restrict countervailing data (e.g., youth unemployment), which can distort government and private sector decision‐making and discourage foreign investment. Posen adds that authoritarian regimes have a long history of starting out strong (fed by government largesse) but inevitably intervene in the economy in “increasingly arbitrary” ways—ways that boost uncertainty, cause households and businesses to hoard cash and avoid risk, and persistently slow economic growth. Once this cycle gets going, it’s difficult to reverse without fundamental reforms, none of which appear to be on China’s horizon.

So, far from being fueling prosperity, Chinese state capitalism and autocracy could be an anchor in ways Japan never had to deal with.

Summing It All Up

Despite all the similarities and my own personal biases, I remain reluctant to embrace China’s “Japanification” narrative for numerous reasons. Most notably, China today fundamentally differs from 1990s Japan in ways—politics, foreign policy, level of government intervention in the economy, human rights issues, sheer size—that make this cross‐country comparison even more difficult than such analogies usually are. And, it should be noted, many of the same analysts talking about “Japanification” are quick to follow with notes about how China might avoid Japan‐style stagnation because its economy today is in some ways better off than Japan’s was in 1990, and because the Chinese government has more “policy space” to act. The precise direction of China’s future economy—lost decade, slower‐but‐steady growth, full‐on collapse, or something else—remains unclear.

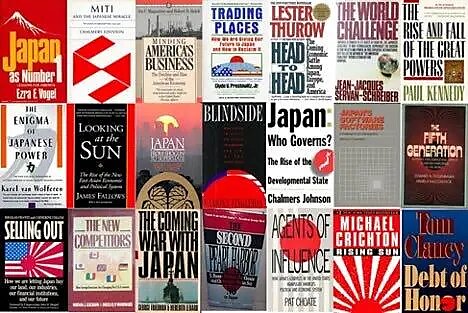

What is clear today, however, is that Xi Jinping’s China is not nearly the unstoppable economic powerhouse that many believed it to be—and wanted the United States to copy—just a short time ago. (See, for example, Cass, Atkinson, Prestowitz, Rubio, Dalio, and Kerry/Khanna to name just a few.) There again lies another parallel with Japan: as R Street’s Adam Thierer documented in 2021 (and as us geezers can recall firsthand), Japanese industrial policy and planning once caused many American wonks and policymakers to predict Japan’s inevitable economic dominance and to propose all sorts of U.S. subsidies and protectionism in response. People wrote books and made movies about the “Japan threat,” and implored Washington to copy Tokyo’s economic model:

That dominance, of course, never materialized. Indeed, just as those books were being published (written by some of the same folks screeching about China today, by the way), Japan was beginning its long period of economic stagnation, with the Japanese government years later admitting that its vaunted economic model was a big part of the problem.

China might not follow the exact same path as Japan, but it sure does seem to be heading in the same general direction. And as we discussed a few months back, there are already plenty of signs that China’s industrial policies aren’t nearly the big winners some have claimed. (More have since emerged, by the way.) One can be forgiven for missing the warning signs in that some of us saw years ago through the fog of positive Chinese economic data. Dire warnings today, however, deserve much less sympathy—and attention.

Hopefully Congress will give them what they deserve.

Chart(s) of the Week

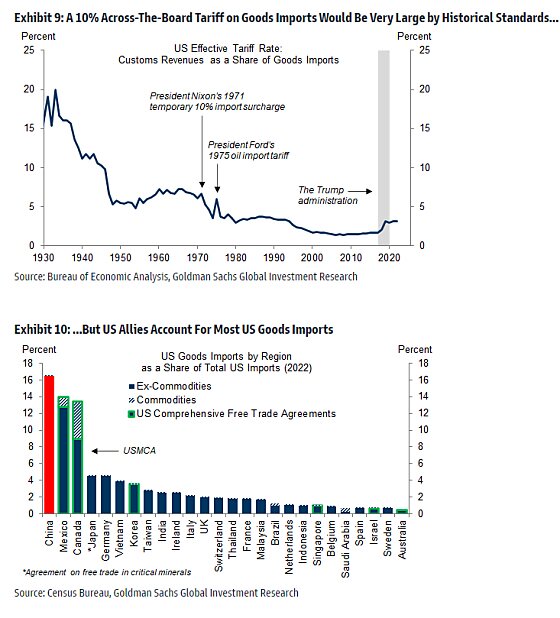

Trump wants historically large tariffs on (mainly) U.S. allies: