Um personagem relevante do fim da Guerra Fria, mas que terminou odiado em seu próprio império...

Morre Gorbachev: como foram as últimas horas antes da dissolução da poderosa União Soviética

- Norberto Paredes - @norbertparedes

- BBC News Mundo

CRÉDITO, GETTY IMAGES

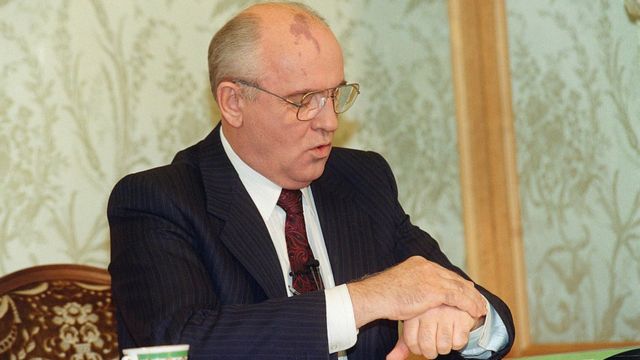

Mikhail Gorbachev, que morreu nesta terça-feira, consultando seu relógio antes do discurso televisionado em que anunciou sua renúncia em 25 de dezembro de 1991

Esta reportagem foi publicada originalmente em 26 de dezembro de 2021 e atualizada em 30 de agosto de 2022.

Foi durante décadas a única potência que poderia rivalizar com os Estados Unidos, até que na noite de 25 de dezembro de 1991, deixou de existir. "Com isso interrompo minhas atividades como presidente da União das Repúblicas Socialistas Soviéticas (URSS)", anunciou Mikhail Gorbachev, no Kremlin, em discurso que rodou o mundo.

Símbolo da derrocada do bloco, Gorbachev era o líder do Partido Comunista e presidente da URSS naquela data. Nesta terça-feira (30/8) foi anunciada sua morte, causada por uma prolongada doença, segundo o Hospital Clínico Central de Moscou. Ele tinha 91 anos.

Para muitos, aquele momento marcou o fim do poder comunista e da Guerra Fria, mas para outros a União Soviética já havia morrido semanas antes com o Tratado de Belavezha.

No entanto, a grande maioria concorda que, após o golpe de agosto daquele ano, a União estava com os dias contados.

Desde a primavera, Gorbachev e seus aliados no governo federal vinham negociando o Novo Tratado da União, que buscava manter a maioria das repúblicas dentro de uma federação muito mais flexível. Eles consideraram que era a única maneira de salvar a URSS.

"Eles queriam manter algum tipo de união, mas com o tempo essa ideia se tornou cada vez menos atraente para os líderes das repúblicas, especialmente para Boris Yeltsin (então líder da República Federativa Soviética Russa)", diz o jornalista e escritor Conor O'Clery, autor de Moscou, 25 de dezembro de 1991: O Último Dia da União Soviética, à BBC News Mundo, o serviço de notícias em espanhol da BBC.

A proposta também foi rejeitada pelos comunistas conservadores, o Exército e a KGB (a agência de inteligência soviética) e então Gorbachev foi colocado em prisão domiciliar em sua casa de férias na Crimeia.

Mas os conspiradores do golpe foram mal organizados e fracassaram depois de uma campanha de resistência civil liderada em Moscou por Boris Yeltsin, que era aliado de Gorbachev.

O golpe falhou, mas como resultado disso Gorbachev perdeu sua influência, enquanto Yeltsin emergiu como o líder preferido dos russos.

"Gorbachev havia planejado a assinatura do Novo Tratado de União para 20 de agosto. Mas o Exército e a KGB consideraram que esse pacto destruiria a URSS como um Estado, e eu concordo", diz à BBC News Mundo Vladislav Zubok, professor de História na London School of Economics (LSE) e especialista em União Soviética.

CRÉDITO, GETTY IMAGES

Golpe de agosto de 1991 foi um dos pontos altos da União Soviética

"O golpe foi uma surpresa, porque aconteceu quando todos estavam de férias. As pessoas esperavam que algo assim acontecesse, mas não em agosto", acrescenta Zubok, autor do livro Um império falido: a União Soviética na Guerra Fria de Stalin a Gorbachev.

'Show televisionado'

Zubok, que nasceu e morou em Moscou durante a era soviética, lembra que muitas vezes as pessoas acreditam na narrativa de que 25 de dezembro foi uma data muito importante, mas em sua opinião não era.

"Quando Gorbachev anunciou sua renúncia, ele não tinha mais nenhum tipo de poder. O que aconteceu foi uma exibição para televisão", diz ele.

Os conspiradores do golpe impediram que o Novo Tratado da União fosse assinado em agosto, mas não puderam evitar a iminente dissolução da União Soviética, que vinha fermentando há anos.

Na verdade, eles lhe deram um impulso.

Depois do golpe, muitos entenderam que a União Soviética havia chegado ao fim, mas outros, incluindo Gorbachev, acreditavam que ela ainda poderia ser salva sob outro tipo de união de Estados soberanos.

CRÉDITO, GETTY IMAGES

Mikhail Gorbachev e Boris Yeltsin no Parlamento após o golpe

"A ideia da União permaneceu atraente para milhões de pessoas que estavam acostumadas a viver em um grande país. Eles esperavam preservá-la talvez sob outro nome ou regime", diz Zubok.

Mas Yeltsin tinha outro plano.

O golpe final

Em 8 de dezembro de 1991, o presidente russo se reuniu com três outros líderes das 15 Repúblicas Soviéticas, o presidente ucraniano Leonid M. Kravchuk e o líder bielorrusso Stanislav Shushkevich, e juntos eles emitiram uma declaração conhecida como Tratado de Belavezha.

Este pacto estipulou que a União Soviética seria dissolvida e substituída pela Comunidade de Estados Independentes (CIS), uma confederação de antigos Estados soviéticos.

Para o jornalista Conor O'Clery, o evento marcou o fim da União Soviética: "Não havia como voltar atrás".

CRÉDITO, GETTY IMAGES

Boris Yeltsin e Stanislav Shushkevich assinando o Tratado de Belavezha em 8 de dezembro de 1991

"Gorbachev não podia aceitar e por duas ou três semanas continuou insistindo que tinham que manter alguma forma de União da qual ele seria presidente", acrescenta.

Mas em 21 de dezembro, oito das 12 Repúblicas Soviéticas restantes aderiram à CEI com a assinatura do Protocolo de Alma-Ata, desferindo assim o golpe final na URSS.

O'Clery diz que foi quando Gorbachev finalmente percebeu o fim de uma era e decidiu que renunciaria em 25 de dezembro com um discurso.

"Yeltsin permitiu que ele ficasse no Kremlin por mais alguns dias e concordou que a remoção da bandeira vermelha do Kremlin seria feita em 31 de dezembro", disse O'Clery.

O historiador Vladislav Zubok destaca que o Protocolo de Alma-Ata foi assinado de forma "extraconstitucional".

"Eles não tinham nenhum poder constitucional para dissolver a União Soviética, mas escaparam impunes. Não os prenderam nem nada", insiste.

"A verdade é que a essa altura já estava claro que o governo central estava completamente disfuncional e o Exército já havia tirado sua lealdade de Gorbachev para dá-la a Yeltsin."

O último dia da URSS

Os dias se passaram sem muitas novidades, até que chegou o dia em que era esperada a renúncia do homem responsável pela perestroika.

Em 25 de dezembro, a maioria dos salões do Kremlin estava calma, exceto por alguns, pois Yeltsin já controlava o complexo presidencial.

CRÉDITO, GETTY IMAGES

Bandeira vermelha foi retirada do Kremlin em 25 de dezembro, embora sua retirada estivesse planejada para 31 de dezembro

Ele nomeou seu próprio comando do Regimento do Kremlin, uma unidade especial que garante a segurança do local, de modo que todos os guardas nas entradas e ao redor dele fossem leais.

Gorbachev mal controlava seu escritório e algumas salas ao redor, usadas por equipes das emissoras americanas CNN e ABC, que se preparavam para transmitir a renúncia.

O'Clery diz que, pouco antes do discurso, Gorbachev teve uma conversa por telefone com o primeiro-ministro do Reino Unido, John Major, que o deixou chateado, então ele mais tarde se retirou para descansar sozinho em um quarto do Kremlin.

"Ele estava muito emocionado e havia bebido alguns drinques quando seu assistente, Alexander Yakovlev, o encontrou chorando na sala", disse ele.

"Foi o momento mais triste de Gorbachev, um momento de angústia. Mas ele se recuperou rapidamente desse episódio e se preparou para fazer um discurso com grande dignidade."

Conforme o planejado, o último líder da União Soviética iniciou às 19h locais um pronunciamento que duraria 10 minutos.

Gorbachev renunciou a seu cargo em um país que não existia mais.

"Agora vivemos em um novo mundo", disse Gorbachev justificando sua decisão.

Zubok insiste que se tratou de um "show televisionado". A CNN traduziu e transmitiu o discurso para todo o mundo via satélite.

De acordo com especialistas, as palavras de Gorbachev tiveram mais ressonância no exterior (onde ele ainda gozava de grande popularidade) do que em casa.

CRÉDITO, GETTY IMAGES

Yeltsin já controlava o Kremlin quando Gorbachev fez seu discurso de renúncia

"Na televisão soviética, o discurso foi visto muito pouco. Gorbachev já era extremamente impopular na União e quase ninguém estava interessado. A essa altura todos sabiam que a União Soviética havia morrido", diz Zubok.

O historiador concorda que foi um pronunciamento "digno", mas ressalta que ele causou descontentamento até dentro das fileiras do Partido Comunista.

"Ele defendeu seu mandato, nunca reconhecendo nenhum erro. Até algumas pessoas ao seu redor ficaram surpresas. Esperavam que ele dissesse algo sobre por que a perestroika deu tão errado, por que não havia nada nas lojas ou por que a economia estava despencando. Mas não", acrescenta Zubok.

"Ele continuou a ver a perestroika como sempre, como uma missão global. E encerrou sua presidência com a moral elevada. Ele não queria mostrar fraqueza a Yeltsin e é por isso que Yeltsin ficou extremamente chateado depois daquele discurso e se recusou a se encontrar com Gorbachev."

O'Clery diz que Gorbachev poderia ter mostrado mais generosidade e apreço por Yeltsin em seu discurso.

"Yeltsin o salvou após o golpe. Se não fosse por ele, Gorbachev teria acabado na prisão ou pior", diz.

A ira de Yeltsin

O'Clery observa que Yeltsin ficou tão zangado com Gorbachev que ordenou que a bandeira vermelha fosse removida imediatamente, embora tivesse planejado retirá-la no final do ano.

Yeltsin também redigiu um decreto na mesma noite ordenando que todos os pertences pessoais de Gorbachev e de sua esposa fossem removidos do complexo presidencial, apesar de ele já ter dito que o casal poderia permanecer no local por mais alguns dias.

CRÉDITO, GETTY IMAGES

Às 19h32, a bandeira soviética foi substituída pela da Federação Russa

Às 19h32, a bandeira soviética foi substituída pela da Federação Russa.

"Gorbachev voltou para casa e encontrou sua esposa em meio a livros e fotos que os subordinados de Yeltsin haviam jogado no chão", conta O'Clery.

Yeltsin e Gorbachev não se viram novamente depois daquele discurso.

Um sinal da baixa popularidade de Gorbachev na Rússia pôde ser visto no momento em que a bandeira da URSS foi retirada do Kremlin: a Praça Vermelha de Moscou estava praticamente deserta.

Às 19h32 daquela noite histórica, a bandeira soviética foi substituída pela da Federação Russa, sob o comando do que por acaso foi seu primeiro presidente, Boris Yeltsin.

E naquele exato momento, o que havia sido por décadas o maior Estado comunista da história foi oficialmente dividido em 15 Repúblicas independentes: Armênia, Azerbaijão, Bielorrússia, Estônia, Geórgia, Cazaquistão, Quirguistão, Letônia, Lituânia, Moldávia, Rússia, Tadjiquistão, Turcomenistão, Ucrânia e Uzbequistão.

Ao mesmo tempo, do outro lado do mundo, os Estados Unidos acabaram se consolidando como a única superpotência global naquele momento.