Containers of Dodge trucks awaiting shipment to Russia under the lend-lease agreement, August 1943. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Alfred T. Palmer, photographer (LC-USE6-D-002838)

In 2022, we wait with bated breath to see how Putin will mark “Victory day”, the day of celebration that marks the Soviet Union’s defeat of Nazi Germany. Meanwhile, in Washington DC as well, they are summoning the ghosts of the past. If Putin evokes the Great Patriotic war, on our side the references are to the Cold War, World War II, the spirit of the enlightenment, ancient battle of democracy against autocracy and so forth.

To offer lessons and inspiration at times of crisis is a classic role for history. Indeed, it is, perhaps, the classic role for public history, But, in this role, history is closest to myth-making. It serves as much to close off, as to open debate. “We all know that appeasement was a disaster, so …. ” etc etc.

To deny the significance of history in this role would be naive and unrealistic. After all, sometimes we need to act and often we need inspiration.

But, there is also a role for critical history. Not to prejudge the question at hand but precisely to ensure that quasi-mythic history is not being used to foreclose the evaluation of the options that are available to us and the likely consequences of those decisions. Capsule histories, long ago smoothed into triumphant narratives promise outcomes far neater than what we can actually expect.

In this sense, critical history is not merely academic pee-shooting. It is part of the daily struggle to preserve a realistic attitude. It is part of the daily struggle to orientate ourselves in medias res - in the middle of things - in the actual middle of the actual things, here and now and not in the 1940s.

During the spring meetings of the Bretton Woods institutions a few weeks ago, the talk was of the Marshall Plan. I discussed in the New Statesman and in a previous Chartbook whether that example is really relevant to our situation.

The historical Marshall Plan was more complicated and less massive than is commonly imagined. It was also a postwar program. That does not mean that the Marshall Plan was innocent in geopolitical terms. On the contrary, it was a key driver of Cold War division of Europe. By the 1950s it merged with US military assistance to drive the rearmament of Europe and Asia. But the Marshall Plan is not remembered for starting World War III. Instead, we invoke it like a comfort blanket - a big fix for a big problem with a happy end.

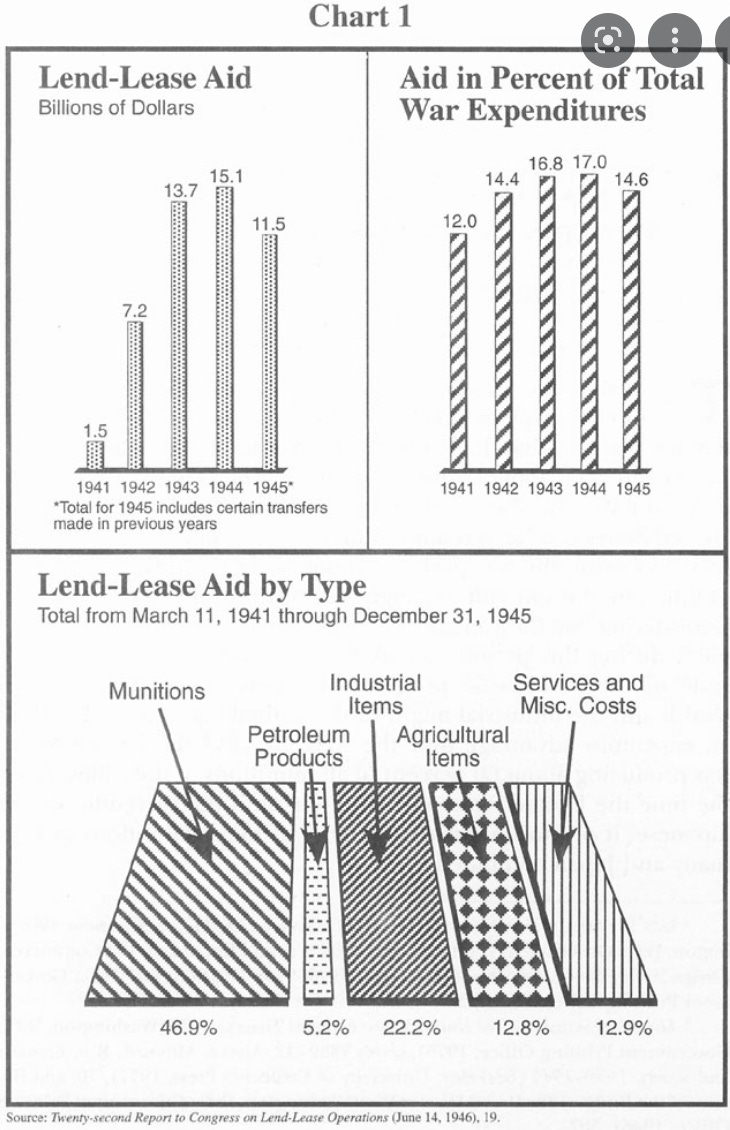

The program under which America bankrolled and supplied Allied victory in World War II was Lend-Lease. Launched in March 1941 It was originally intended to back the British Empire, Greece, China in their separate struggles against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. After the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union American assistance was extended to the Soviet Union as well.

Vastly larger than the Marshall Plan and launched into a middle of on-going wars, Lend Lease was a dramatic act of escalation. As the best known history of Lend-Lease remarks: “The Lend-Lease Act marked the point of no return for American policy regarding Hitler’s Germany.” Lend Lease tied together the separate struggles in Europe and Asia to create by the end of 1941 what we properly call World War II.

Source: Hyperwar

It is striking - to say the least - that already in January 2022, before Putin’s invasion, the US Congress had taken up Lend-Lease as the historical inspiration for a legislative measure that frees the Biden administration’s hands in providing aid to Ukraine.

The Ukraine Democracy Defense Lend-Lease Act was unanimously approved by the Senate and passed by the House of Representatives by a vote of 417 to 10. Now, according to remarks made by press secretary Psaki, Biden may sign it into law on May 9th.

Will a new Lend Lease Act be America’s answer to Putin’s “Victory day”?

As well-informed defense journalists point out, the Lend Lease Act of 2022 adds very little to Biden’s already extensive powers to support to Ukraine. Far more consequential in that regard are the $33 billion in additional aid that Biden has requested. But that isn't the point of the Congressional measure:

… this is the actual genius of the Ukraine Democracy Defense Lend-Lease Act. Even if the exemption of certain lease provisions isn’t going to do anything that existing authorities don’t already cover, invoking the memory of Lend-Lease is an entirely different issue. Frankly, nobody will wax poetic about the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act. … But Lend-Lease is a term that is ingrained in the American story.

… it’s the spirit of the law that’s vital here. … Achieving something other legislative proposals have not, it has set the proper tone for the conversation. The clear decision of the American people, as represented in Congress, to put the power of American industrial might, guided by Ukrainian hands, into the fight against Russian aggression.

“The American story” was very much to the fore, when, in supporting the measure in the House, Speaker Nancy Pelosi invoked the legacy of her fatherwho was one of the House members who followed FDR’s call to vote for the original bill.

81 years ago, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt came here to the Congress of the United States, to the House of Representatives – where I’m proud to say my father, Thomas D'Alesandro, served as a Member of Congress – and President Franklin Roosevelt delivered a bold and historic request.

Symbolism aside, the scale of the aid now being envisioned by the Biden administration is unprecedented. As Ben Freeman and William Hartungpoint out at Responsible Statecraft

if Congress signs off on this new request the U.S. will have authorized $47 billion in total spending to Ukraine. That’s more than the Biden administration is committing to stopping climate change and almost as much as the entire State Department budget.

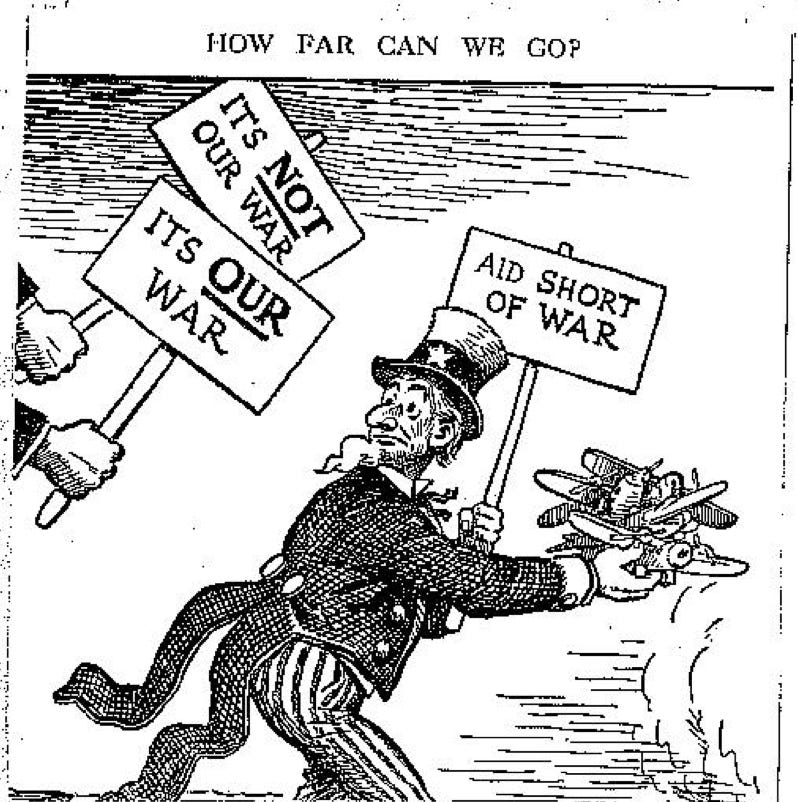

This is twice the maximum amount of money ever provided in a single year to the Afghan army (as opposed to money spent by the US in Afghanistan) and seven times the US military aid budget for Israel. The total request amounts to one third of Ukraine’s prewar GDP. As far as Ukraine is concerned, the US is bankrolling a total war effort and the US political class has with near unanimity declared that the appropriate historical analogy for this effort is 1941 - “All measures short of war”.

As Lockheed Martin has announced it is ramping up production of Javelin anti-tank missile systems to meet the unexpected surge in demand. As Chief executive James Taiclet announced.

“I went over to the Pentagon with my team and basically told the senior leadership there, ‘Look, we’re already investing in increasing the capacity, please make it right and give us the contracts and agreements we need down the road, but we’re going to start investing now,’”.

In a short piece in The Guardian last week I queried what the implications might be of this discursive move. What history are we summoning in evoking the Lend-Lease act of 1941?

Last year, the 80th anniversary of 1941 saw the publication of three substantial books that throw new and often alarming light on that moment.

As Stephen Wertheim - one of the founders of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft - spells out in his book Tomorrow, the Worldfollowing the collapse of British and French resistance on the continent of Europe to early 1941, American strategists shifted from the Wilsonian stance of wanting to arbitrate world affairs from a vantage point of armed neutrality, to a full-throated interventionism. What was now envisioned was that that the United States should reshape the world order through direct and massive engagement on a global scale. Though this shift in strategy began within the Roosevelt administration in 1940, it was in 1941, with Lend Lease, that it broke into the open.

In order to supply the fight against the Axis, Roosevelt sought the assent of Congress, as he had not done over the destroyers deal (in 1940). He wagered that noninterventionists, if brought into the open, would suffer a crushing defeat. He was right. The Lend-Lease Act, debated in January and February and passed in early March, removed the cash-and-carry restrictions and empowered Roosevelt to designate future recipients of aid. Under international law, no neutral could assist a belligerent as America was aiding Britain. Interventionist lawyers thus decided that America was not a neutral. Led by Quincy Wright, the political scientist and international lawyer, they popularized the category of nonbelligerent to characterize the U.S. position.31 By shedding the vestiges of neutrality, Roosevelt freed up interventionists to think and speak about the kind of world for which the Anglophone Allies stood. Even before the LendLease Act passed, Borchard lamented that noninterventionists had been “out-shouted.”32

Roosevelt’s wager that he could defeat the non-interventionist would be vindicated. But as Wertheim reminds us it was more of a stretch than the bards of the “American story” might be comfortable remembering.

In 1940-1941, polling by Gallup showed considerable opposition to greater intervention in the war against Hitler and Mussolini. The original Lend-Lease act passed through Congress against far tougher opposition than the revival of the Act has faced in 2022. Eventually, it passed the House by 260 to 165 and the Senate 60 to 31.

As Wertheim points out, it was in the course of the Lend-Lease debate, in February 1941, that Henry Luce launched his appeal for his fellow Americans to take up the mantle of the “American Century”, an idea that continues to hang over the “American story” today.

The question that must haunt us today is whether Lend Lease in 1941 set America on an inescapable path towards war. Both critics and supporters of FDR always insisted that Lend Lease had in effect set a trap. As Warren F Kimball reports in The Most Unsordid Act. Lend-Lease 1939-1941

A day or so after Roosevelt’s announcement of the Lend-Lease idea, Hull (Secretary of State) remarked to Breckinridge Long (Assistant Secretary) that, depending upon Hitler’s actions, America could be in the war within ten days or six months. Long, who was closely akin to Joseph Kennedy in his views of the situation, was more inclined to believe that America’s belligerency would depend on the amount and type of aid given to Great Britain. Either way, both men found their thoughts running in the direction of war as a result of the President’s newly announced program.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Britain of course devoutly hoped that Lend Lease was just the beginning and the US would soon be dragged, willy-nilly into the war. As the debate raged, Britain waited anxiously to know how the Congressional vote would go. As Kimball reports,

H. Duncan Hall, who was attached to the British Embassy in Washington at the time, captured the tense emotion: “For the first time in its history the United Kingdom waited anxiously on the passage of an American law, knowing that its destiny might hang on the outcome. London waited with an imperfect knowledge of American legislative processes and little understanding of American public opinion.” 73 The effects of the Great War, long hidden from public view, had wrought a permanent change in the Britain of Castlereagh, Kipling, and Churchill. The king was dead—long live the king!

But, as Cordell Hull had remarked, assuming that American public opinion would not back a unilateral declaration of war by the United States, the future depended not on Washington or London, but on the reaction in Berlin.

In Wages of Destruction, back in 2006, this is how I described the reaction of Germany to the announcement of Lend-Lease.

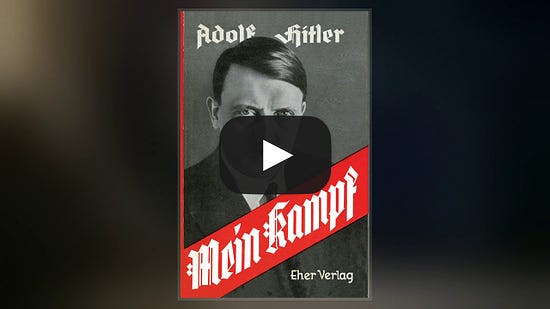

The first line of the report from the Washington embassy on lend-lease, received by the Foreign Ministry, the Wehrmacht high command, the army and the Air Ministry, stated bluntly: 'The Lend-Lease Act currently before Congress . . . stems from the pen of leading Jewish confidants of the President. It is intended to give him the possibility of pursuing without limitation his policy of influencing the war through all means "short of war". With the passage of the law the Jewish world-view will therefore have firmly asserted itself in the United States.' It then went on to itemize the huge deliveries that could now be expected by 'England, China and other vassals'.46

For me, as for Tobias Jersak and an interpretive line that runs back to Saul Friedländer’s early book Prelude to downfall: Hitler and the United States 1939–1941 (1967), Lend Lease was a key moment in the escalating tension between the United States and Nazi Germany that impelled not just military strategy but also the radicalization of the regime’s racial policy.

The idea that FDR was under the control of Jewish influence did not originate with Lend-Lease but in earlier antagonism between the Third Reich and the United States. The attention of Nazi racial ideologues had shifted to the US over the winter of 1938-1939 following FDR’s denunciation of the Kristallnacht pogrom and the so-called war of words between Hitler and the White House.

Most openly the coming confrontation with the United States was anticipated by Hitler in his ominous speech to the Reichstag of 30 January 1939 in which he linked the prospect of a world war i.e. a war with the United States, to the threat that European Jewry would be annihilated.

Throughout 1939 and 1940 German military planners paid anxious attention to America’s armaments efforts and purchases in the US by Britain and France. Regime literature directed towards the inner core of the Nazi party and the SS was studded with references to Jewish influence in the United States.

Against this backdrop, Lend-Lease was a dramatic escalation that confirmed the Nazi’s worldview. Britain and the United States were linked in an antagonistic alliance, motivated by dark forces bent on Germany’s destruction.

In the compass of the very short Guardian piece, the editors and I decided to bracket this dimension of the history of 1941. It is simply too explosive and too easily misread as some kind of absurd equation between Hitler and Putin. But if you want to wrestle with the actual history of Lend Lease you cannot side step its entanglement in Hitler’s Manichean anti-semitic worldview.

2021 saw the publication of two new historical studies that reinforce this line of interpretation. As we learn from Klaus Schmider’s meticulous reconstruction of the build-up to the German declaration of war on the United States on December 11, in Hitler’s Fatal Miscalculation (2021), Hitler was, indeed, deeply concerned about Lend-lease. As he told his entourage on March 24 1941:

‘the Americans have finally let the cat out of the bag; if one felt so inclined, it would be legitimate to interpret this as an act of war. He was now in a position to allow a war to break out without further ado. However, right now, it was not something he was keen on. The war with the US was sure to come sooner or later anyway. Roosevelt and the Jewish financiers have no other choice to than to strive for this war, since a German victory in Europe would mean enormous financial losses for the American Jews. It is merely regrettable that as yet no planes existed which could bomb American cities. This is a lesson he would like to teach the American Jews. To be sure, this new Lease Law would bring him additional major problems. He had now come to the conclusion that its success could only be prevented by ruthless naval warfare.’

When Hitler met Japan’s Foreign Minister in April 1941 he told him that war with the United States was already “taken into account”.

As Lend-Lease deliveries ramped up, this set the stage for the Atlantic Charter meeting between FDR and Churchill on 14 August 1941, from which would emerge the United Nations. That too, as Tobias Jersak first argued, was interpreted in Berlin as a tightening of the global conspiracy against the Nazi regime. And that had ominous implications.

Throughout the autumn of 1941 as the struggle on the Eastern Front entered its climactic stage, references multiply to Hitler’s prophecy i.e. his Reichstag speech of 30 January 1939.

In his address to the troops of Army Group Centre on 2 October ahead of the final push to Moscow (operation Typhoon), Hitler linked the decisive battle for Moscow directly to the racial struggle not just on the soil of the Soviet Union but worldwide. Germany was now at war both with Bolshevik Russia and capitalist Britain, behind which stood the United States. Superficially different, the two economic systems were in fact fundamentally alike. Bolshevism was no better than the worst kind of capitalism. It was a creator of poverty and destitution and 'the bearers of this system', 'in both cases', were 'the same: Jews and only Jews!’ The assault on Moscow was to deliver a 'deadly thrust' against this arch-enemy of the German people.”

Hitler’s problem was how to conduct that global war. Without a powerful navy or a strategic air force he had few ways to strike at the British Empire, let alone the United States. It was that calculation that ultimately bound Nazi Germany to Imperial Japan and drove Hitler towards his declaration of war on the United States on December 11.

As Brendan Simms and Charlie Laderman make clear in their extraordinary reconstruction of the events between Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war, Hitler did not stumble into war, his declaration of war on December 11 1941 was a deliberate gamble.

Simms and Laderman’s book deserves far more attention than it has received. Its effort to reconstruct a week in global history - perhaps the most fateful week in history - on a minute by minute basis strikes me as a fascinating and original way of writing the history of an “event”. Others may know better, but I have never read a historical account that starts with a map of global timezones. In the current moment, it is hauntingly evocative.

The pay off from Simms and Laderman’s meticulous blow by blow account is to sharpen our sense of how vertiginously contingent the escalation to global war seemed in the second week of December 1941, even as it was happening. Above all they highlight the fact that the immediate impact of Pearl Harbor was not to confirm the logic of Lend Lease but - to the horror of London and Moscow - to cause Lend Lease to be suspended. If Hitler’s intention was to ally himself with Japan so as to divert resources from the Atlantic to the Pacific, his strategic vision was, for those few days at least, massively confirmed.

Indeed, as Simms and Ladermann argue, FDR was convinced that Japan was acting essentially as a German proxy. He refused to credit Japan with strategic autonomy. Hitler knew better and it was with a view to binding Japan to the German cause that he took the decision to declare war on the United States. After all, as far as Hitler was concerned, war between Germany and the United States was already “taken into account”.

As Simms and Ladermann remark:

It was Hitler’s declaration of war on the United States, much more than Pearl Harbor, that created a new global strategic reality and, ultimately, a new world. America did not enter “the war”—the conflict with Hitler—on December 7, 1941. Rather, the United States was plunged that day into a new and initially separate struggle against Japan. America did not truly join the war until December 11, 1941, and unlike the First World War, the United States did not take the initiative. It was, as British air marshal Arthur Harris had predicted, “kicked into the [European] war.”

As Roosevelt’s speech writer Robert Sherwood put it, Hitler had followed Japan in solving Roosevelt’s “sorest problems”. For Hitler too this was a moment of culmination. On 12 December, the day after Hitler’s declaration of war, Goebbels spoke to the Gauleiter, the regional officials of the Nazi party, and spelled out the connection.

“Regarding the Jewish question, the Führer is determined to clear the table. He warned the Jews that if they were to cause another world war, it would lead to their own destruction (30 Jan 1939). Those were not empty words. Now the world war (the war with the USA, AT) has come. The destruction of the Jews must be its necessary consequence. This question is to be regarded without sentimentalism. We are not here to have sympathy with the Jews, but rather with our German people. If the German people have sacrificed 160,000 dead in the eastern campaign, so the authors of this bloody conflict will have to pay for it with their lives.”

It was no coincidence that within a few weeks of Hitler’s declaration of war on the United States, Reinhard Heydrich and the State Secretaries would convene at the conference center on the Wannsee to scheme out what they called the final solution of the Jewish question in Europe. Originally, the Wannsee meeting had been scheduled for December 9 1941. It marked the culmination of a year-long planning project that had been set in motion over the winter of 1940-1941 when the invasion of the Soviet Union and the global escalation of the war came clearly into view. Heydrich’s meeting was put back to 20 January 1942, on account of the crisis on the Eastern front and the declaration of war on the USA.

Behind the sugar-coated narrative of a “good war” won by the “arsenal of democracy” - “the American story” evoked in Congress in recent weeks - lurks the actual history of the haphazard and contingent unleashing of an apocalyptic world war. To complete the picture, it was in October 1941 that Roosevelt issued an executive order green-lighted the atomic bomb program and cooperation with the British on scientific research.

****

In openly declaring our intention to adopt all measures short of war to ensure Russia’s military defeat and in invoking Lend Lease in doing so, we must surely ask ourselves that question, what is our theory of Putin? And beyond Putin what is our model of the escalatory dynamics at work in 2022?

In swathing ourselves in historic garments, are we inviting Putin to do the same? Are we inviting him to fully inhabit the role of the maniacal dictator who can only be crushed out of existence? Are we, as in 1941, crossing the point of no return? Are we, consciously or not, assuming further escalation?

In so doing, are we assuming that escalation will have the same kind of “happy end” that World War II eventually had for the United States in 1945? The kind of “happy end” that makes Lend Lease into a myth shrouded in good feelings - a grand chapter. in the “American story”?

Or, are we, in fact, hoping that 2022 unfolds as 1941 did not? That Putin is not suicidal? That this time the escalation remains confined to Ukraine and Russia? That this becomes, as some American strategists envisioned Lend Lease in 1941, a calculated exercise in using the dogged resistance of a client - then the British now Ukrainians - to attrit a geopolitical antagonist?

These are not comfortable questions. So much so that merely raising them can lay you open to accusations of defeatism. But that is beside the point. Supplying weapons may well be the best thing to do under the circumstances. It is certainly what the Ukrainian government is asking for. But to weigh the consequences of our actions and the risks attendant on them, to assess the costs and who pays them is a basic imperative of responsible politics. In so doing we need a clear head and democracy demands that clarity is not just something that is achieved behind closed doors.

Ukrainians at this moment may need history to give them courage. For us to revel in mythic references to the 1940s and “the American story” is a shameful, sentimental self-indulgence. If we are to evoke the past at all, let us do so in a critical and exploratory fashion, not to “prove” facile points one way or another, but to better understand how we arrived at this moment and to infer what its possibilities and risks might be.