Poucas coisas são tão definidoras do estado de confusão permanente que é o Brasil quanto o prédio situado na Avenida República do Chile número 65. É ali, no centro do Rio de Janeiro que situa a sede da Petrobras.

Eleito um dos prédios mais feios do mundo em votação popular, a sede disfuncional, que aparenta faltar pedaços, tal qual o Brasil, o prédio é a primeira grande obra da Odebrecht fora da Bahia, e que a catapultou como uma das maiores construtoras do país. O ano de construção é sintomático, 1969, o 5º do regime militar, também o ano em que a ditadura “endureceu”.

Assim como o crescimento das torturas e perseguições políticas do regime militar, que saltaram de pouco de 100 em 1968 para mais de 700 em 1969, após a promulgação do AI-5 (O 5º dos 17 Atos Institucionais da ditadura e que ampliava os poderes do presidente fechando o congresso), o período marca o início de um intervencionismo sem fim, responsável por produzir a ilusão, que reina até hoje, de que gerou evolução ao país, ao menos no campo econômico.

É bem verdade que a ditadura foi responsável por 20 das 23 maiores hidrelétricas do país hoje, a despeito de seu nulo respeito por questões ambientais (típico de ditaduras, que o diga a União Soviética e as dezenas de reatores nucleares simplesmente jogados no oceano), mas o regime militar, assim como qualquer governo, é muito mais do que obras. A construção do desenvolvimento é um processo longo e pouco aparente, ao contrário das faixas e placas de inauguração, e justamente por isso quase sempre ignorado.

A política definida por Delfim Neto, o mais jovem e poderoso ministro da Fazenda que o Brasil já teve, como “fazer o bolo crescer para depois dividir”, é também sintomática, como as obras fraudadas que levaram nossas empreiteiras a despontarem no Brasil e no mundo.

Para Delfim, o crescimento econômico era uma soma de dois fatores: capital e trabalho, e por capital, leia-se, máquinas e equipamentos. Não passava pela cabeça do ministro, como jamais passou pela cabeça de qualquer assessor econômico em qualquer regime ditatorial, que o capital pudesse ter outra forma que não vultosas somas de recursos definidas em Brasília.

Durante o período da ditadura, nossa educação patinou com média de tempo de escolaridade de 2,4 anos para homens no início e 2,6 ao final dos anos 70. A média é cerca de ⅓ da atual, na ainda sucateada educação brasileira. Sem grandes avanços na educação, também não há qualquer notícia de que o povo tenha sido chamado para definir o crescimento do país. Não há grandes empreendedores na época fora do círculo do poder, há obras e mais obras, muitas delas, o suficiente para alimentar e engordar um cartel inteiro de empreiteiras.

O chamado milagre econômico, o período no qual chegamos a crescer 14% em um ano, desprezava a criatividade do empreendedor brasileiro e o investimento em educação. Durante o período os gastos com educação diminuíram de 7,8% para 5% do PIB.

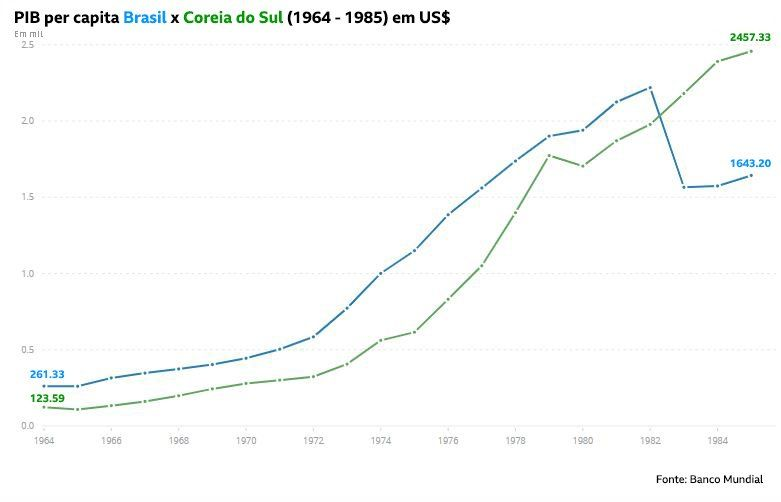

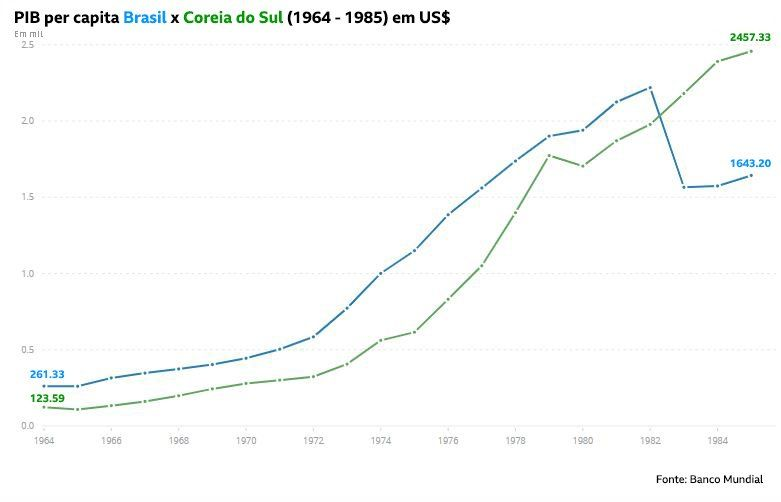

No mesmo período, apenas para ficarmos em um exemplo, o Brasil viu a Coreia do Sul saltar de menos da metade do nosso PIB per capita para uma riqueza média 50% maior do que a nossa, em um processo fortemente calcado em educação.

Com o mundo em plena Guerra Fria, linhas de crédito eram uma maneira segura de manter próximos países em desenvolvimento, e foi ali que baseamos nosso crescimento. Usando o cartão de crédito para reformar a casa. Durante o período de 1975 a 1983 apenas, os Estados Unidos colocaram US$ 315 bilhões em empréstimos para a América Latina (US$ 1,57 trilhão em valores atuais), ou cerca de 50% do PIB da região.

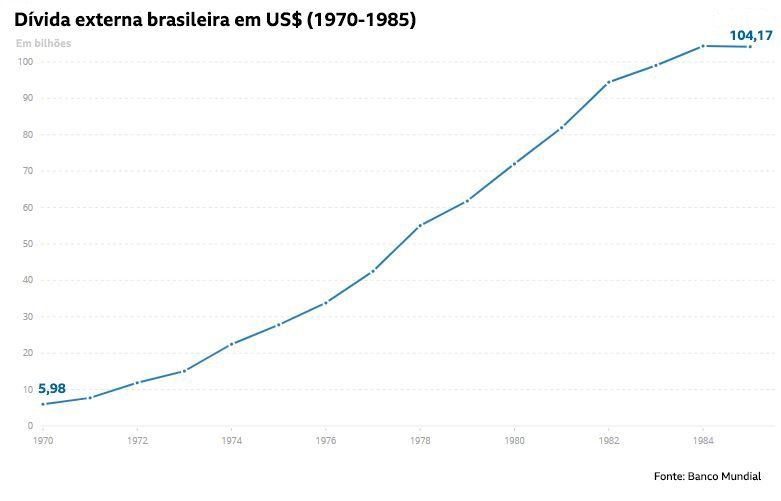

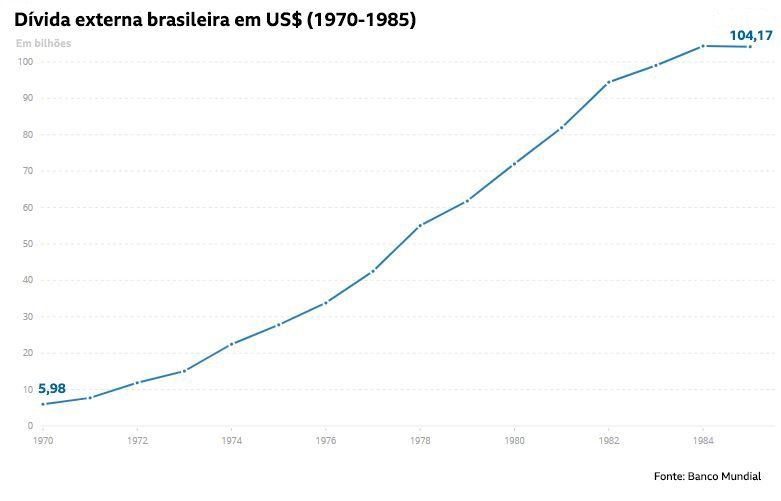

No Brasil, nossa dívida externa saltou de US$ 3 bilhões para US$ 102,7 bilhões, ou 53,4% do PIB. Se mantida a proporção sobre nossa economia, a dívida herdada da ditadura equivaleria a US$ 1,1 trilhão. Para lhe situar melhor, nossa dívida hoje está em R$ 4,45 trilhões, ou US$ 870 bilhões em uma conversão nominal.

Em suma, terminamos o regime militar devendo até a alma, e chegamos a 1985 prestes a declarar moratória, pedindo “arrego” aos bancos internacionais (fato que ocorreu em 1987). Por ano o país gastava US$ 11 bilhões apenas em juros (números de 1982), o equivalente a 6% de toda a riqueza produzida no Brasil.

O resultado que seguiu a essa explosão de endividamento tem um nome marcante, importado do México, que passava por problemas similares, resumidos como “Década perdida”.

Os anos 80 foram bem mais que uma série de tentativas frustradas de conter a inflação durante a presidência de um proeminente político da ditadura, agora travestido de civil, José Sarney. Passamos anos, ao menos 9 para sermos mais precisos, lutando para controlar a inflação herdada do regime militar.

Nos tornamos graças à leniência do período o país com maior inflação da história do ocidente sem termos passado por uma guerra civil.

A cifra, que chegou a 13,42 trilhões de % nos 15 anos que antecederam o plano real, chegou a cair no começo da ditadura com reformas no governo Castelo Branco, que domou o dragão derrubando o índice 92% para 15% entre 1964 e 1969. Com o início do milagre econômico, até mesmo essas medidas ficaram de lado, e o índice explodiu para 242,42% em 1985.

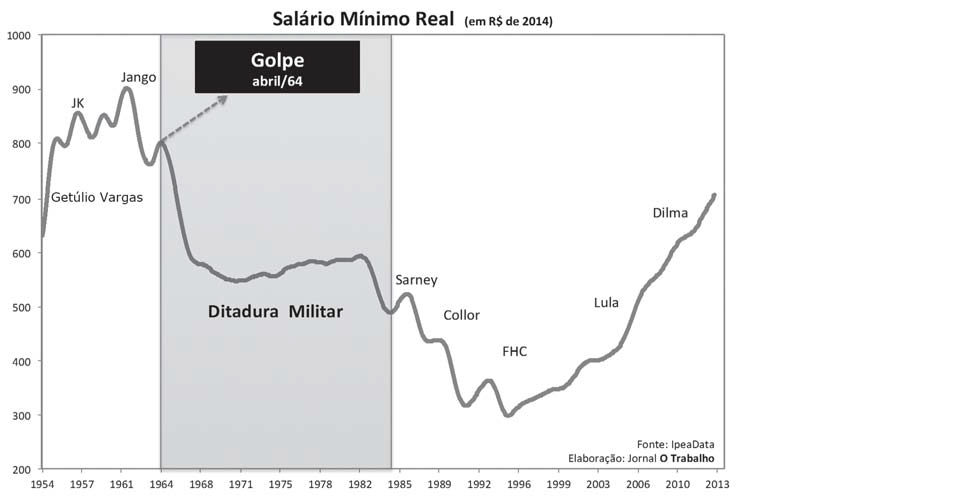

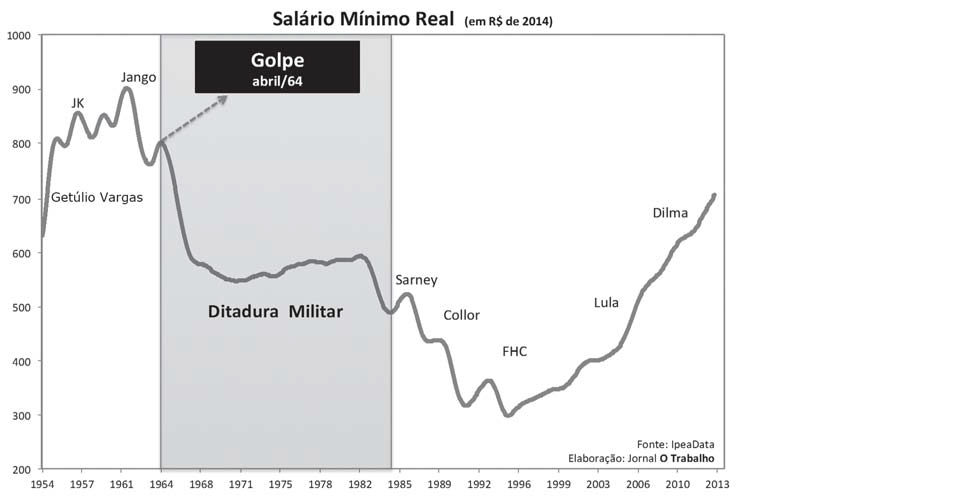

Como mostraram Simonsen e Cysne, a inflação era parte do orçamento da união, como um imposto escondido e cobrado justamente dos mais pobres. Não por um acaso o período ficou conhecido como um grande arrocho salarial. Não apenas Delfim alegava que os mais pobres deveriam esperar o bolo crescer para então dividir, como também acaba por arrematar parte dos salários dos mais pobres. Entre 1964 e 1985, o salário médio caiu de R$ 1024 para R$ 620 em valores de hoje.

Nos tornamos um dos países mais desiguais do planeta, com uma elevada concentração de renda, tudo para permitir um milagre de crescimento que alimentava uma elite industrial. E aqui, cabe um pequeno parênteses. Se você é um liberal, ou conservador, daqueles que admira Thatcher, não tente enganar a si mesmo dizendo que “desigualdade não importa, o que importa é a pobreza”. A desigualdade que fez Bill Gates o homem mais rico do mundo após criar um sistema adotado por bilhões de seres humanos e torná-los mais produtivos, não é a mesma desigualdade criada para alimentar a Odebrecht ou Camargo Corrêa. Essa, além da desigualdade também gera pobreza.

Nem só de roubar os mais pobres via inflação e endividar o país vinha o crescimento brasileiro do “milagre econômico” porém. Durante o período, o êxodo rural foi fortemente incentivado. Talvez não seja tão simples enxergar onde entra o crescimento nisso, mas imagine que você pegue hoje um trabalhador rural do Crato, no Ceará, e o coloque para operar um trabalho manual na Siderúrgica do Pecém, também no Ceará. Se na zona rural este trabalhador produzia R$3 mil/ano, na siderúrgica, com o capital acumulado e o ganho de eficiência da indústria, este trabalhador irá produzir R$50 mil (em valores abstratos, claro).

Nosso ganho demográfico também colaborou e muito, para gerar este crescimento. Como qualquer ditadura, não houve incentivos para o aumento produtividade, fator essencial para o crescimento de longo prazo. Desde os anos 70 nossa produtividade segue na mesma, sem qualquer sinal de que vá melhorar.

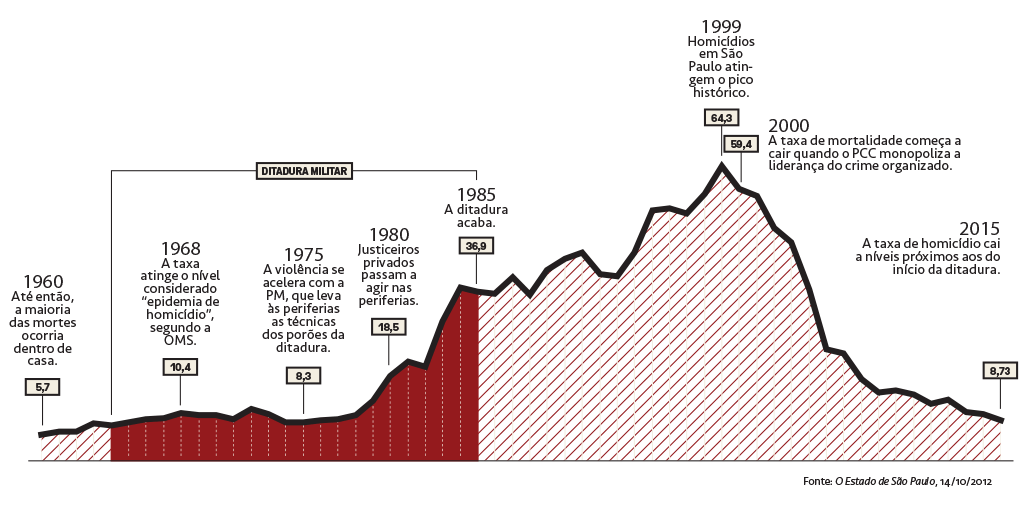

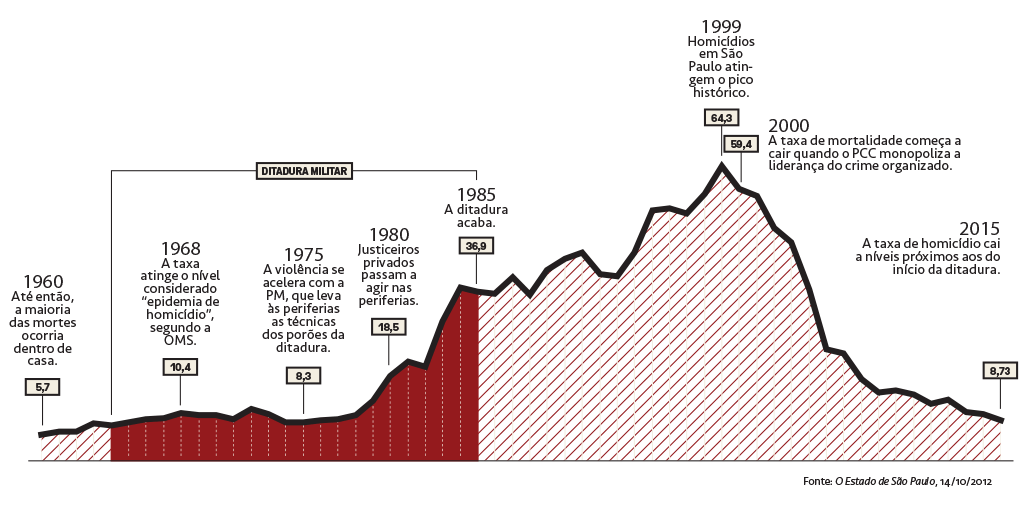

Outro fato legado pelo êxodo rural, além das mortes no campo, foi um aumento na criminalidade das cidades, inchadas e sem qualquer planejamento. Em São Paulo por exemplo, os homicídios subiram de 6 por 100 mil habitantes para 35 por 100 mil entre 1960 e 1985.

Se você ainda tem dúvidas de que a desigualdade não era acidental, mas um projeto, foque nos números. Durante o período os 5% mais ricos da população aumentaram sua participação na renda nacional em 9,6% do PIB, enquanto os 80% mais pobres perderam 9,3%.

Também naquela época o funcionalismo público ganhava destaque. Em algumas estatais, como a Eletrobras, a prática de distribuir lucros mesmo quando havia prejuízo já existia – prática revertida apenas em 2019, conforme esclarecimento prestado pela assessoria da empresa*-, e muitos funcionários recebiam até 17 salários por ano.

Como escreveu o jornalista Ricardo Kotscho em 1976, época em que a censura começou a diminuir, ministros contavam com até 28 empregados em casa, gastos com aluguel, energia, água e telefonia arcados pela união, e claro, voavam em jatinhos da FAB. Os que não tinham cargos tão relevantes para utilizar aviões da FAB, podiam sempre requisitar lugares em aviões da Varig, a Viação Aérea Rio-Grandense, empresa símbolo do regime e que contava com monopólio bem assegurado pelo regime.

Assim como o crédito e o endividamento das famílias, que crescia 23% ao ano entre 74-79, época do “milagre”, o número de estatais se multiplicava. Foram 247 ao longo dos 21 anos da ditadura, cerca de 1 nova estatal todo mês.

Durante o período país mantinha a lei de nacionalização do petróleo criada por Vargas e que impedia investimentos privados no setor, o que só foi derrubado em 1997. Apesar disso, a Petrobras mantinha-se pouco atuante. Nos tornamos dependentes de importação do petróleo, que representava 40% da matriz energética brasileira, e dependia de importação para suprir 81% da demanda, contra 51% no início do regime militar.

A bomba armada pelo peso do Estado na regulação e pela atuação nula para expandir a produção, foram cruciais para deixar o país vulnerável durante o choque do petróleo. Sob um dirigismo estatal, lançamos o pró-álcool para tentar amenizar, mas o fato é que mesmo este era um movimento que monopolizava as decisões em Brasília.

Sem tribunais de controle externo e com a censura instaurada na imprensa, a corrupção ficava debaixo do tapete. Para as viúvas da ditadura, os militares morreram pobres, para os fatos, além das inúmeras benesses pagas até hoje, muitos foram os que enriqueceram graças ao festival de obras públicas.

Voltando ao caso da Odebrecht, a empreiteira baiana era uma mera construtora regional durante as grandes obras de Juscelino Kubitschek, e só foi se tornar relevante durante o regime militar, não apenas com a já citada sede da Petrobras, como também pela construção de duas obras cruciais do regime: o aeroporto do galeão e a usina nuclear de Angra dos Reis.

Anos mais tarde, a empresa levaria a construção de Angra II e III, sem licitação, parte do processo que levaria Emílio Odebrecht a depor em uma CPI no senado, em 1979, sobre denúncias de desvios de verba. O resumo da CPI, que terminou abafada, você confere aqui.

Para um país de democracia frágil como o Brasil, acostumados ao descontentamento com a classe política, a história pode parecer um refúgio, em especial quando reescrita. Prezar pela verdade dos fatos e evitar romancear eventos como as ditaduras brasileiras (não apenas o regime militar, mas também o ainda aclamado Getúlio Vargas), é uma maneira de garantirmos que o futuro não repetirá erros do passado.

Não há atalhos para o desenvolvimento e para construir um país justo e próspero para toda sua população. Trata-se de um caminho longo, que deve, em essência, partir da criatividade e empreendedorismo de seus indivíduos, jamais do autoritarismo de alguns.

*Correção – ao contrário do afirmado anteriormente no texto, que apontava que a Eletrobras pagava PLR mesmo quando havia prejuízo, a companhia informou, através de sua assessoria, que houve mudança nas práticas a partir de 2019.

Confira a seguir: “Informamos que a Participação nos Lucros ou Resultados (PLR) da Eletrobras era paga, até 2019, de forma proporcional ao alcance dos indicadores econômico-financeiros e operacionais, o que permitiu em algumas ocasiões distribuir a parcela referente ao alcance dos resultados operacionais mesmo em situação de prejuízo. Porém, diferente do que aponta a reportagem, em linha com as melhores práticas de mercado e em consonância com o contexto atual, a prática vigente de PLR na Eletrobras, já pactuada inclusive com os sindicatos, prevê que só pode haver pagamento de PLR aos empregados no caso de a companhia apresentar lucro. Logo, em caso de prejuízo, nenhum valor é desembolsado.”